There is something childlike in our own Hungarian “Trianon sentiment.” Childlike in the noblest sense of the word. The kind of honest, pure, original shock and indignation of when we are cast into this world, start to become familiar with it, and find ourselves facing an injustice on a disproportionately large scale, which we would like to fix, but simply cannot: the pain and loss of which still lingers.

The pain of Trianon has been a comparable and profound shock for the Hungarian nation. It tends to affect those who understood and truly felt in childhood – due to their family heritage, awareness, or their own early perception – that which had befallen Hungary at the time of our grandfathers and great-grandfathers, one hundred years ago.

The author was raised in a family where such historical topics were discussed at the dinner table, and relevant books linedthe shelves. I became responsive to the issue, and as a member of a frequently travelling family, I visited a number of places beyond the border at a young age.

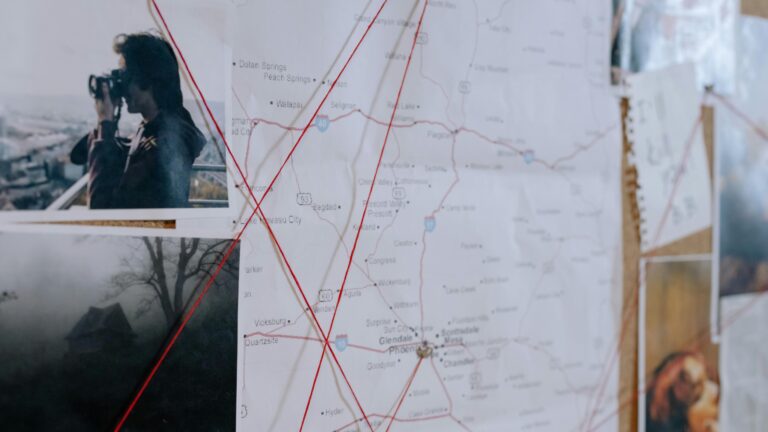

Back then I toured the historic Upper Hungary – Slovakia today – more thoroughly than the current, “Lesser” Hungary where black spots are waiting for me to discover them. I naturally spent a lot of time as a young boy leaning over historical maps, redrawing borders of Greater Hungary in a way that felt fair. By the way, what do you think would have been the best way to resolve the political problem of the multi-ethnic Bánság region? Or, would it have been possible to designate and implement a corridor between the main block of Hungarians and Székelyföld [Székely Land/Szeklerland]? I deeply pondered these great national issues: such is the luxury of youth.

This was the time when I first saw Transylvania – from Gyergyó to Segesvár, from Prázsmár to Nagyvárad – right after the fall of Ceausescu’s regime, whose regional heritage shined through despite its present misery. It was an experience ofa lifetime to complete the ridge hike in the Fogaras Mountains; it provided the perfect, thousand-year-old natural border for the Kingdom of Hungary with their thousand-metre-deep canyons.

As a well-informed child, I could only laugh when a streetwise Romanian guy in the Old Saxon Town of Segesvár wanted to present an old garrison there to us as Dracula’s Castle

Memories keep surfacing, one after the other… As a well-informed child, I could only laugh when a streetwise Romanian guy in the Old Saxon Town of Segesvár wanted to present an old garrison there to us as Dracula’s Castle. My English, acquired early, came in handy when we turned into a pedestrian street below the castle in Trencsén by accident and a Slovakian policeman was right there, eager to hit us with a fine on the spot. I was stunned to see signs in different languages up in the castle on that same day – except Hungarian, of course – labelling it as a stronghold of “Matej Čak, Slovakian chieftain”, who fought against the oppression of the Hungarian kings. Although Máté Csák was a Hungarian nobleman and oligarch, an extraordinary strongman of his time.

At the same time, of course, we had a number of beautiful moments throughout Slovakia’s hostels, or in the lonely shelters of the Transylvanian Fogaras Mountains. In the latter, I planned to spend a night by myself, but a Romanian family arrived and we shared food and admired the mighty mountains together. The mountains which had stood there before us and before the birth of our nations – and shall continue to tower unmoved long after we perish.

I also roamed around the other end of the Carpathian Basin, currently the easternmost region of Austria, perhaps for the first time in the year of the political transition in 1989. I visited the disciplined Esterházy castle and the fortress of Fraknó, and marvelled at the fact that the neighbour’s grass was greener indeed – right at the moment of crossing the border, miraculously.

But I perceived the same qualitative leap when we were bouncing along on our way home to our Lesser Hungary from the Szilágy borderland of Romania, from the village of Érmindszent – birthplace of the famous Hungarian poet Endre Ady –now the edge of the world. Terribly bumpy roads lead us to the border and the rather poor Hungarian county of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg looked as well-groomed as Western Europe, compared with the conditions we saw over the border.

In the same way, I was already a Budapest citizen when I realised with eerie clarity – not for the last, either – how beautiful our capital was when we just returned from a major trip to the Balkans, after departing from a bleak Sofia in the morning, travelling through a somewhat shabby Belgrade, and crossing the Great Hungarian Plain, to see the widescreen view of Budapest from a bridge over the Danube, with the backdrop of the hills and the whole line of bridges, towers, and domes, most of them dating back to the era when Budapest was one of the twin capitals of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the empire ruling almost the entire Central European region at the time.

This force, this calm strength based on more than a thousand years of our history with our rich national heritage and our unique Hungarian culture, is still radiating today in the entire Carpathian Basin. Here, whether chauvinistic national neighbours like it or not, there are those who subscribe to the mantra, “let us not be afraid of being small”. I like this radiating strength.

Indeed, I also like the massive, unshakable, indestructible mooring posts, the cast-iron bollards in the seaport of Fiume (today’s Rijeka in Croatia), with the Hungarian inscription still legible now, deep into the twenty-first century:

“SCHLICK’s IRON FOUNDRY and MACHINE WORKS L.T.D. BUDAPEST”

The company was founded by Ignác Schlick, of Swiss descent, who put down his roots in the Hungarian capital to start his business, which grew into a robust operation, not only casting those port bollards in Fiume, but also putting out complex products including the world’s first low-floor streetcar. Ignác Schlick, Hungarianized, found his final resting place in the National Cemetery on Fiume Road, Budapest.

The bollard I saw in Fiume first as a kid, excited to read the Hungarian words on it, also keeps remembering Mr. Schlick, who had foreign roots but contributed with his work to the prosperity of the country we used to share, the former Central Europe of convenient and peaceful coexistence; the organically developing Kingdom of Hungary within it.

I do hope that with a bitter century behind us, we can step on the road to a new age in alliance with the people around us; optimally, for a new Central Europe, with our nations in cooperation with one another and living in harmony. This is, perhaps, how the next century could be for a disintegrated Central Europe: the healing of wounds and grievances between the nations that constitute it.