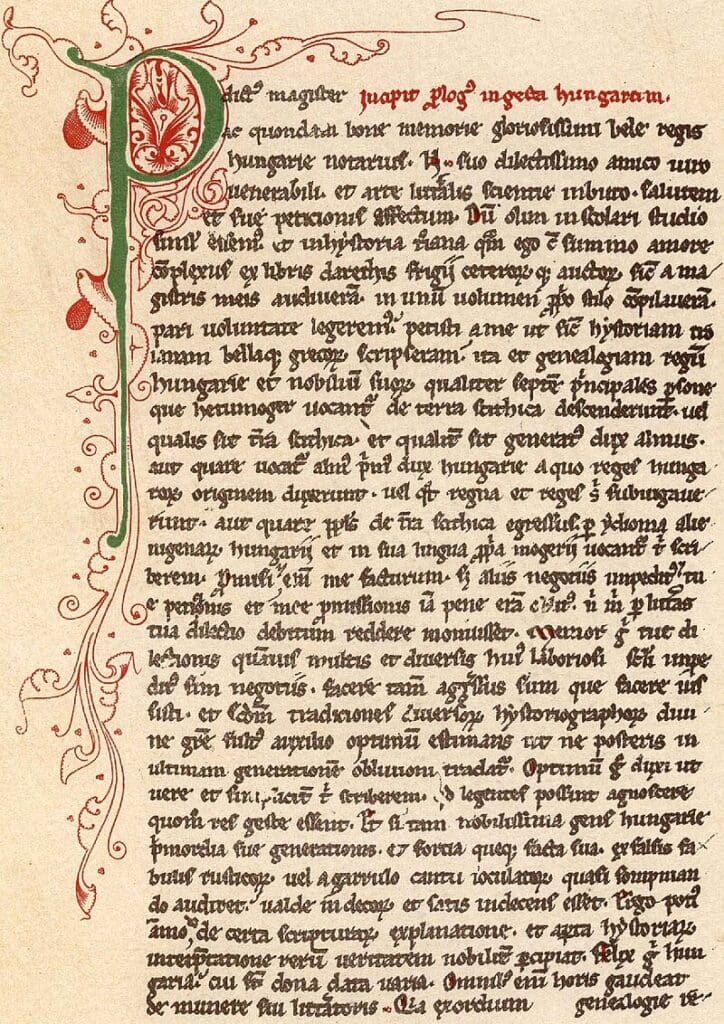

‘P. who is called master and sometime notary of the most glorious Béla, king of Hungary of fond memory, to the venerable man N. his most dear friend steeped in the knowledge of letters’—thus begins the medieval chronicle of Hungarian history that is the most debated to this day, Gesta Hungarorum, or The Deeds of the Hungarians.[1]

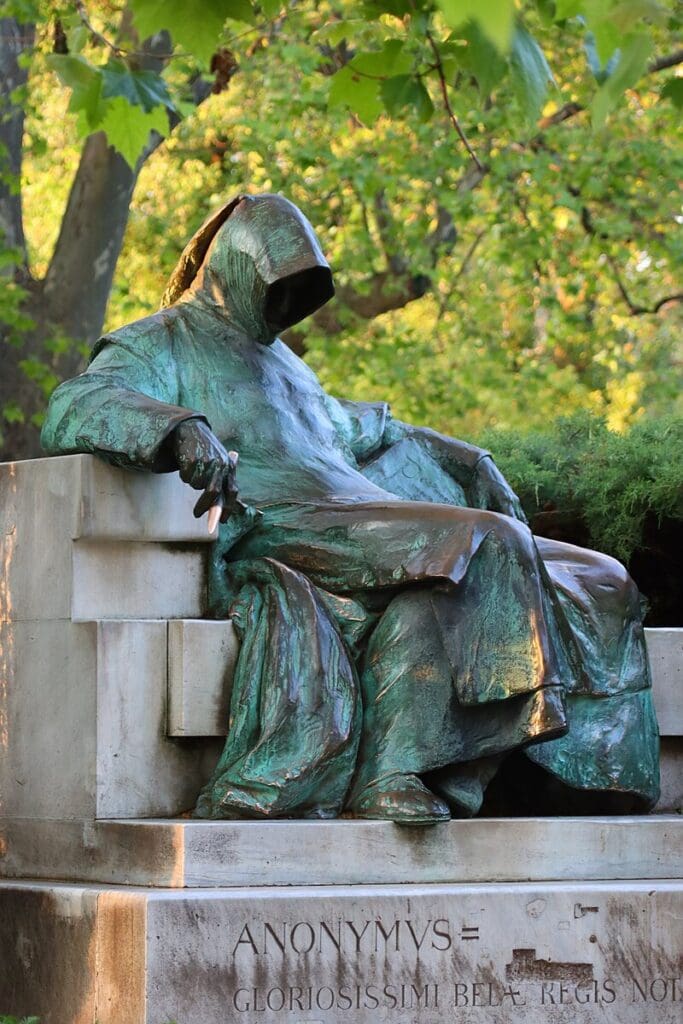

But who was the author who abbreviated his first name as ‘P’, or which of the four kings named ‘Béla’ of Hungarian history did he serve, not to mention his mysterious friend? Despite all the uncertainties, the chronicle written by Master P., or as he is known to many because of the obscurity of his person since its discovery, Anonymus, has been one of the most important documents of the search for Hungarian historical consciousness and identity. An evidence of this is the fact that its first Hungarian translation was completed as early as 1790, and the reprint edition that came out in the 1970s sold tens of thousands of copies in Hungary. The host of articles penned by amateur historians appearing even nowadays in newspapers and magazines prove that it is still the anonymous author who has the largest readership of all medieval historical sources. In addition, what makes the chronicle even more exciting is that

it is the one with the oldest surviving manuscript version.

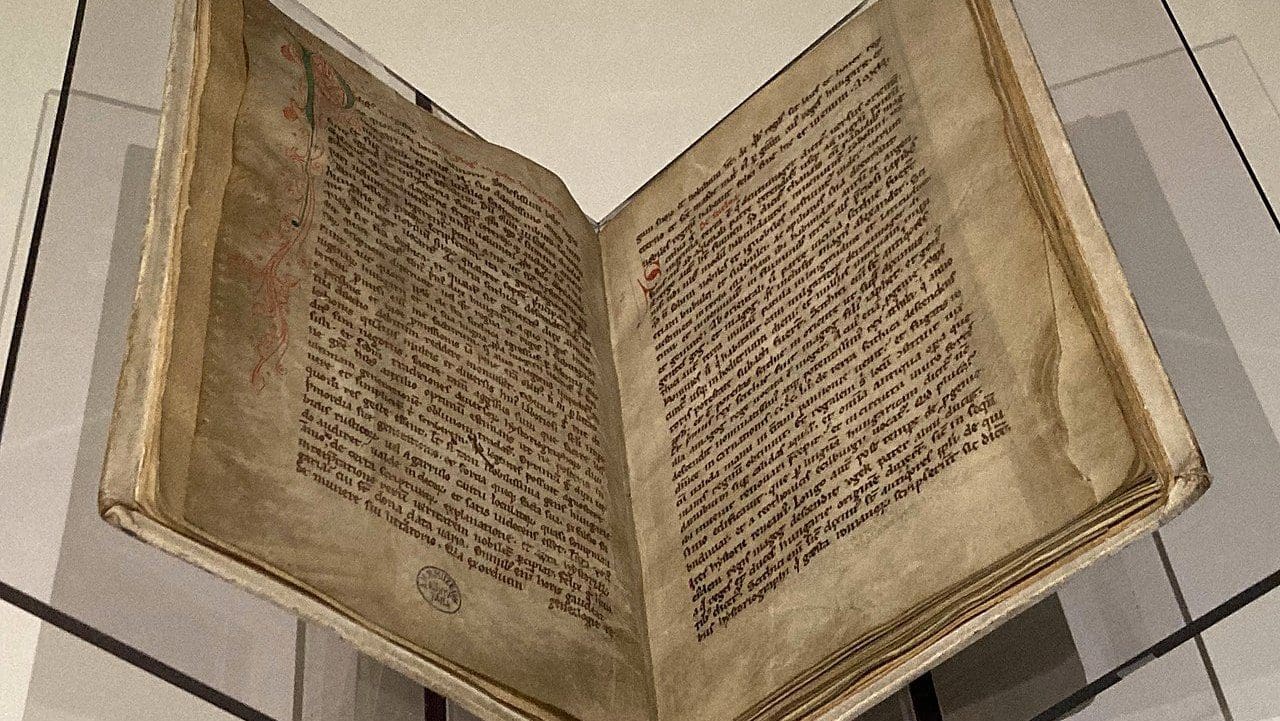

A 13th century copy of the chronicle can be found today in the National Széchényi Library in Budapest, and is very short, consisting of only 24 folios, i.e. a total of 48 pages.

The author’s aim was to present the origins, the migration, the conquest of the homeland, and the territorial expansion efforts of the Hungarians. Accordingly, he traced their journey from their ancestral homeland beyond the Black Sea, Scythia, through the Russian principalities to the Carpathian Basin. The protagonist of the story is Prince Árpád, the eponym of the Árpád dynasty, which ruled until 1301—on the other hand, there is only a brief reference made to the time of Saint Stephen (r. 997–1038) and the conversion of the Hungarians to Christianity. The chronicle is a story of the pagan Hungarians, who were nevertheless led by the Holy Spirit to their new homeland, as a chosen people. The relationship between the people and events depicted in the work and the sites mentioned in written sources or documented by archaeological excavations is still the subject of much debate. It is difficult to give a definitive opinion on the matter, but it is certain that the work has very little to do with the historical process we call the ‘Hungarian conquest’. The perspective of several hundred years, however, correctly showed the author the historical, or it is perhaps no exaggeration to say so, the world-historical significance of the Hungarian conquest. But for specific details, he had no choice but to rely on the use of contemporary 12th-century heroic songs, Western chroniclers, and, of course, the Bible. Naturally, these heroic songs usually contained what the noble dynasties of the time wanted to hear: they told of the self-sacrificing struggle of their ancestors and of their blood-earned possessions, which they then acquired by right through princely donations, too. Unfortunately, contemporary 10th-century Western chroniclers such as the German Regino of Prüm had no direct knowledge of the events either, and could only provide information about their historical context. They, too applied the 3rd-century chronicler Justinus’ description of the Scythians to the Hungarians, which was subsequently incorporated into the Hungarian chronicles as well. Thus, our author was obviously forced to borrow the stylistic elements of his story from Western narrative prose such as the tales of Troy or the stories about Alexander the Great.

It must be mentioned that the value of the work is not at all diminished by the fact that it looks back from a span of several hundred years to the era of the seven chieftains of the Magyars: it provides one of the most coherent and linguistically most outstanding works of medieval Hungarian literature. Nor is it to be underestimated that the practitioners of medieval studies and source criticism in Hungary learned their craft and perfected their methods through this very work.

The afterlife of the chronicle begins with the discovery and publication of the copy in the imperial library in Vienna in 1746, and that is when it enters the canon of Central European historiographic literature. The most prominent scholars of the day, including August Ludwig von Schlözer (1735–1809), a professor at Göttingen University, were initially enthusiastic, mainly because of the work’s references to early Russian history. However, once they recognized the author’s sources, they changed their opinion, calling Master P. a ‘storyteller’ (Fabelmann in German), an ‘uncultivated monk’ (unkultivierter Mönch), and a ‘deeply ignorant ecclesiastic’ (tiefunwissender Geistlicher). For a long time, however, this chronicle was given full credit in Central Europe, and only gradually did it become established that

it gives a picture of the Hungarian conquest mainly on the basis of the oral traditions of the author’s time,

but even more so on the basis of contemporary place names and personal names. Even today, many people still refuse to believe that the work was written more than 300 years after the end-of-the-9th-century Hungarian conquest, and in order to increase its credibility, they try to trace its origins back to the earliest possible time, to the mid-11th century. Some believe that Master P. may have been working on the basis of a lost 11th-century Hungarian chronicle, but there is no evidence whatsoever to underpin that belief.

The two fundamental and interrelated questions the research into the chronicle aims to find answers to are the identity of the author, the identification of the already deceased, ‘most glorious Béla, king of Hungary of fond memory’ mentioned in the introduction, and ultimately the dating of the work. Of the two problems, researchers have only been able to provide a satisfactory answer to the latter. Already since the 19th century, there has been a growing consensus that the mentioned King Béla can be identified with one of the greatest kings of early Hungarian history, Béla III (r. 1172–1196). This is also supported by the reflection in the work of the high standard of Hungarian cultural life and of the military campaigns the king conducted during his reign.

As for the author, it is certain that he had been abroad, to France or Italy, as it was a fashionable thing to visit foreign universities in the time of King Béla III, and then probably used his knowledge and experience in the royal administration. The titles notarius (meaning ‘notary’) and magister (‘master’) mentioned in the work also suggest this. Besides, perhaps as so many of his learned peers did, he rose to a high ecclesiastical office, but unfortunately, we do not have a complete list of bishops and abbots of the time.

A fundamental tenet of the research is that Master P. drew far-reaching historical conclusions from the geographical names he was familiar with in the country, of places where he himself may have personally travelled as a member of the itinerant royal court. It was not without reason that he thought that the country’s past was reflected in its geographical names, which in many cases originated from the people who had lived there or who had been its first owners. But he may also have travelled outside the country’s borders as a royal envoy, as the Balkan place names included in the chronicle, far from the borders, show. Perhaps the mention of the present-day Bulgarian Gates of Trajan, the Greek Neopatras (now Ypati), or the Albanian Durazzo (now Durres) are all the memories of a Byzantine mission.

Another question relates to whom the chronicle was really made for. There is a clear reference in the work to the songs of the minstrels, who recorded the deeds of the nobility, and the incorporation of heroic songs into the structure of the work. The large landowners of the time may not have minded the birth of the chronicle either, but there is no doubt that the royal court played a certain encouraging and commissioning role in it. It is even possible that during the king’s lifetime, a longer dedication may have been the starting point of the book, which, however, became meaningless with his death. It may also have been intended to be distributed internationally, as King Ladislaus IV did with Simon of Kéza’s work in the late 13th century. In any case, the only surviving copy suggests that the death of Béla III rendered the work obsolete. The political objective of the work, in fact, was to prove the legitimacy of the Hungarian conquest against Byzantine claims, which a political issue typically in Béla III’s time.

Likewise, two scenes defining Hungarian political thought can be considered among the modern details of the work as well. Even before the Hungarian conquest began, the seven chieftains of the Magyars unanimously and by public will accepted the leadership of Árpád’s father, Álmos, in the so-called Blood Oath. To confirm their commitment under the oath, they mixed their blood in a vessel according to ancient nomadic customs, thus entering into a mutual obligation whereby they secured the right to resist their leader: ‘if any of the posterity of Duke Álmos and of the other leading men should seek to breach parts of their oath, they should be put under an everlasting curse’. The event was considered, with some exaggeration,

to be the birth of Hungarian parliamentarism and part of the Hungarian historical constitution, a kind of basic law.

The limitation of royal power by contract and the refusal of loyalty to the king if his rule was considered illegitimate were not alien to contemporary thinking. Traces of this can be found not only in the middle of the 12th century with John Salisbury, but also around 1205 with the Polish Wincenty Kadłubek, followed by the English Magna Carta in 1215 and the Hungarian Golden Bull of 1222.[2]

Later, after the successful conquest of the Carpathian Basin, ‘the duke [Árpád] and his noblemen ordered all the legal customs laws of the realm and all its rights, how they should serve the duke and his leading men, and how they should judge any crime committed…and the place where all these matters were ordered the Hungarians called according to their language Szer, because here was ordered the whole business of the realm.’[3] The public still believes that the first Diet was held in Ópusztaszer in Southern Hungary, in memory of which a National Heritage Park was established there, and where Hungarian painter Árpád Feszty’s 1800-square-metre artwork, the Arrival of the Hungarians, otherwise known as the Feszty Cyclorama, was presented in 1894.

The work attracted the attention not only of Hungarians, but also of historians of all the nations mentioned in the text: from the 18th century onwards, Slovak historians, through the mentions of the Slavs, and Romanian historians, through the Vlachs, have paid great attention to the work.[4] Given the fact that there is no written record of the presence of the Romanians in the Carpathian Basin before 1200, especially in Transylvania, Master P. became particularly important for them, since, according to the work, they had already settled in the area before the Hungarian conquest. Romanian readers are paying the work considerable attention to this day: an enlarged photograph of the front cover of the chronicle has long highlighted its historical importance in the National Museum in Bucharest, and in 1987, the Romanian government paid for an advertisement to promote the work in The Times.[5] Of course, the nations who were left out of it, such as the Germans who had already been living in the country in large numbers by the time, were suspicious of it from the start. Master P. mentions the Slavs in what is now Slovakia but is silent about the Moravian Principality, which in turn provoked criticism from 18th-century Slovaks. It is no coincidence therefore that in addition to German and English, modern Slovak, Polish, and Romanian translations of the chronicle have also been produced.

As a result of domestic research in the last decades,

Master P.’s work is considered a novelistic chronicle based on the place names, sagas, and Western chronicles of around 1200,

a writing that has historiographic ambitions, but which is basically a piece of literature, only coincidentally related to the real events of the Hungarian conquest.

Yet there is nothing to condemn the medieval Hungarian chroniclers for in their record of the conquest as they did their utmost to make use of the oral traditions of Hungary and the Western European written traditions of the age of the conquest, and to develop a Hungarian historical chronology by consulting the pages of contemporary world chronicles. It is not their fault at all that they found so little information about the given period that they had to expand it with elements of Western European fiction—even so, the picture they have created is a beautiful and complete one. Perhaps too much so, as a result of which the critical study of the written sources and artefacts relating to the conquest remains a serious challenge to this day.

[1] Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy (trans., eds.), Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians, Budapest–New York, 2010, p. 3.

[2] Grischa Vercamer, ‘The Origins of the Polish Piast Dynasty as Chronicled by Bishop Vincent of Kraków (Wincenty Kadlubek) to Serve as a Political Model for His Own Contemporary Time’, in The Medieval Chronicle, Vol. 11, Leiden, 2017, pp. 227–230.

[3] Anonymus, p. 87.

[4] Alexandru Madgearu, The Romanians in the Anonymous Gesta Hungarorum, Cluj–Napoca, 2005.

[5] Laszlo Peter (ed.), Historians and the History of Transylvania, Boulder, CO, 1992, pp. 197–201.

Related articles: