When planning a visit to the Vatican Museums, the first thing that comes to many people’s minds are the frescoes of Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Commissioned by Pope Julius II, the Sistine—named after his uncle Pope Sixtus IV—bears witness to a revolutionary concept the ‘divine artist’ introduced into art. It was not the fact that he painted a ceiling, for the Emperor Nero’s Domus Aurea had such decorated vaults. Inspired by the rebirth of classical antiquity proposed by the humanists, Michelangelo applied the twisting movements of human sculptures onto paint, thus providing the onlooker with dramatic and illusory effects.

Such endeavours to explore the human dimension had been emphasised by Francesco Petrarca, commonly known as Petrarch (1304-1374). Recognised as the ‘Father of humanism’, he advocated for a studia humanitatis (humanist education) that mimicked the education of Classical antiquity. This in turn accentuated the human capacity for growth and innovation. Yet there is another work of genius in the Vatican Museums, overlooked at times by tourists, that depicts the visual embodiment of the rebirth of classical humanist philosophy and art that gave the Renaissance its name: the School of Athens by Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (Raphael).

Raphael adorned the locale with four works of art, each exemplifying the four branches of knowledge during the Renaissance

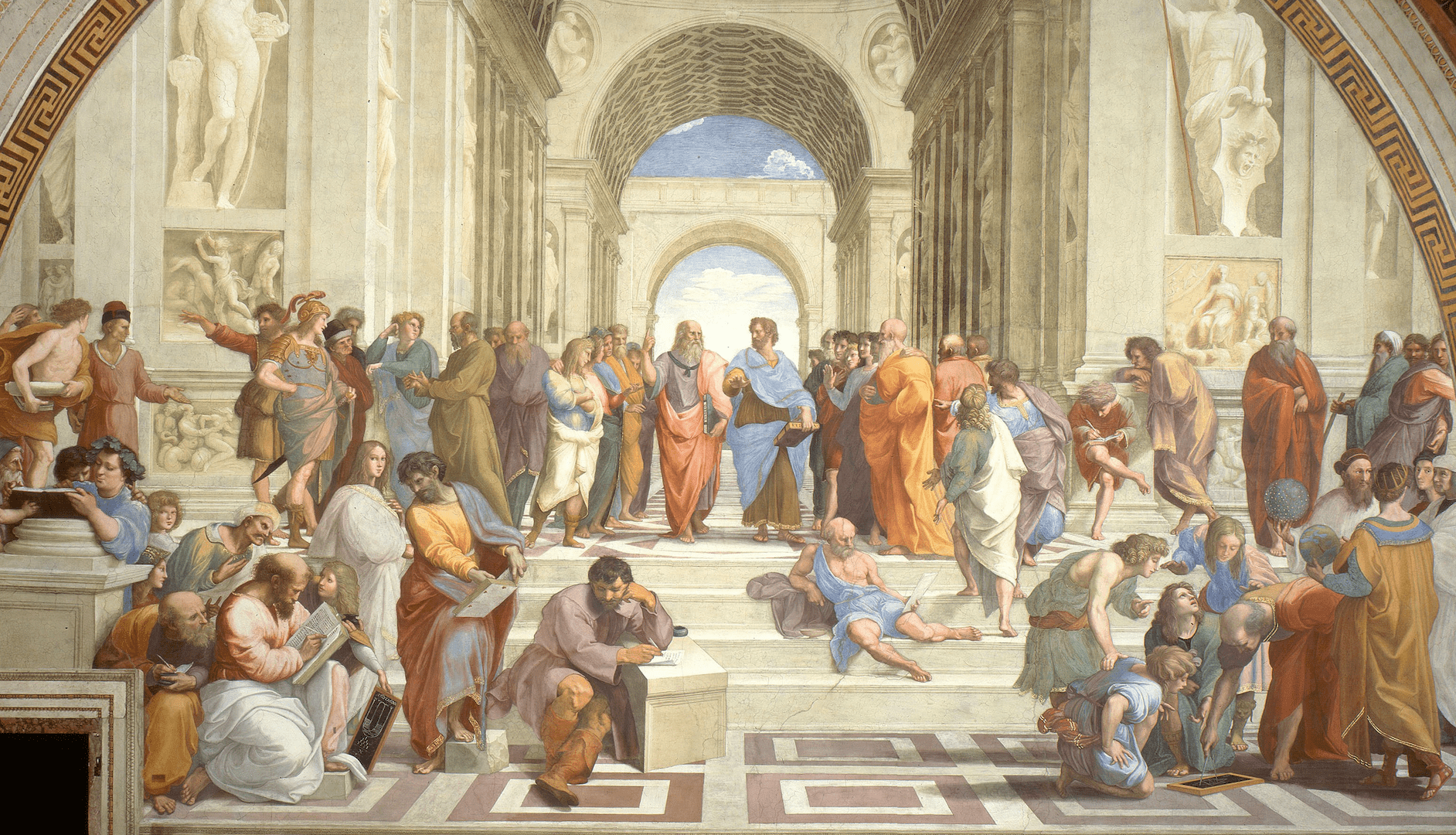

At the behest of the aforementioned soldier pope, Raphael was asked to decorate four walls of the Stanze della Segnatura—the place where the Church’s most significant documents were signed, sealed, and set into enforceable doctrine. Raphael adorned the locale with four works of art, each exemplifying the four branches of knowledge during the Renaissance: the Disputation of the Most Holy Sacrament and its victory over any arguments against it (Theology); Mount Parnassus (Poetry); Jurisprudence (Justice); and The School of Athens, painted between 1509-1511, which symbolises Philosophy.

In The School of Athens he portrays the greatest of pre- and non-Christian intellects from Antiquity up to his time. Situated in the centrepiece under an archway, reported to be in the design of St Peter’s Basilica, are the philosophers Plato and Aristotle. The former is gesturing towards the sky, a nod to his Theory of Forms, which teaches that our physical world is not the ‘real’ world, but it is instead a spiritual realm composed of abstract thoughts and ideas. The latter, in direct opposition to Plato, has his hand outstretched towards the audience symbolising empiricism, the epistemological theory that argues that our reality stems primarily from sensory experience. Both philosophers are holding a copy of a text supporting their respective theories—Plato holds his book The Timaeus, while Aristotle holds Ethics; Plato is flanked by Apollo, the god of music and arts, while Athena, goddess of wisdom and reason, hovers next to Aristotle.

There is, however, a double irony in The School of Athens. The first is, as already mentioned, is that there are no Christian figures, aside his mistress, Margarita Luti, and his own self-portrait. Instead, one sees, for example, the mathematician Euclid, the Andalusian philosopher Ibn Rushd, better known as Averroes, the philosopher of happiness Epicurus, and the pre-Socratic and Ionian philosopher Heraclitus.

The second paradox is that Raphael’s pièce de résistance represents, in a broad sense, the (Neo-Platonic) Academy of Athens that the Christian Emperor Justinian permanently shut down in 529. It was not so much the physical building, in as much as the teaching of (pagan) philosophy (and Judaism) the then emperor saw as a threat to Christian society. Raphael’s intention, as per Julius II’s, was not to provoke, let alone imbue anti-Catholic teaching. Instead, he wanted to highlight reason as a pillar of the Christian faith. Perhaps this is most likely why directly opposite The School of Athens he painted the Disputation of the Most Holy Sacrament, which embodies ‘a celestial vision of God and his prophets and apostles above a gathering of representatives, past and present, of the Roman Catholic Church and equates through its iconography the triumph of the church and the triumph of truth.’

Humanists held that the wealth of classical culture allowed them to do fine, noble deeds

Humanism gave precedence to the development of human virtue, as depicted in the classical works of Cicero and Livy. This, however, was never a negation of divine or supernatural matters. According to their philosophy, humanists held that the wealth of classical culture allowed them ‘to do fine, noble deeds, that good citizens needed a good, well-rounded education and that moral and ethical issues were related more to secular society than to spiritual concerns.’ Hence the reason why Julius II and other Renaissance popes dedicated so much attention to art.

Raphael, as with his like-minded contemporaries, believed philosophical reasoning was essential to express Christian faith at a time when the institutional Catholic Church was humanly handicapped by the corruption of some of its own members. (It was this depravity that ultimately caused a separation within the Church with Martin Luther and Protestantism.) In their fundamentalist interpretation of Holy Scripture, they not only took it upon themselves to pick and choose whatever doctrine suited them, they simultaneously rejected the contribution of humanism and the beauty of how art could inspire both the intellect and the soul.

Let us not forget what St Thomas Aquinas said when he quoted Aristotle: ‘the principle of knowledge is [derived from] the senses.’ (Summa Theologiæ, Ia, Q. 84, art. 16.) But there are also those things, as the Angelic Doctor says, that the soul cannot perceive from the senses. The humanist movement, as Raphael’s School of Athens showed, contributed to both.