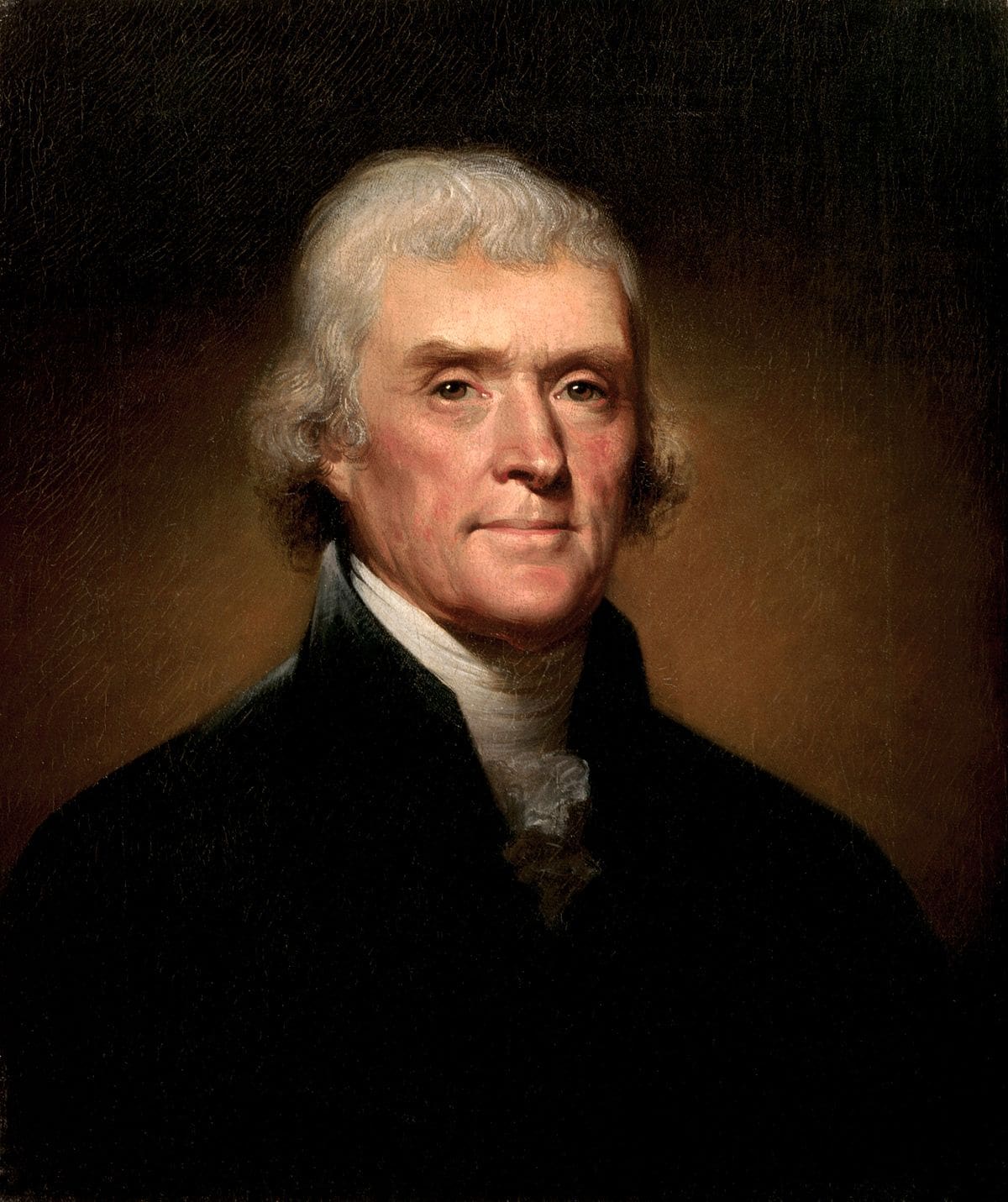

Today marks the 246th anniversary of American colonists declaring their independence from the British Crown, the day when, as an independent and sovereign nation, the United States of America proclaimed liberty, justice, and freedom for all. The pivotal point of departure was the Declaration of Independence—the first government document to recognise man’s natural rights (of ‘Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness,’)—which was authored by Thomas Jefferson, the champion of individual freedom and natural rights.

These American principles, which have historically been put to the test innumerable times, could not have been better recapitulated than by Pope Benedict XVI during his visit to the White House on 16 April 2008:

‘From the dawn of the Republic, as, America’s quest for freedom has been guided by the conviction that the principles governing political and social life are intimately linked to a moral order based on the dominion of God the Creator. The framers of this nation’s founding documents drew upon this conviction when they proclaimed the ‘self-evident truth’ that, [as written in the Declaration of Independence] all men are created equal and endowed with inalienable rights grounded in the laws of nature and of nature’s God. ’

In recent years, however, because of the left-wing woke movement, the reputation of the Declaration of Independence has been tainted. In April of 2019, then presidential candidate Joe Biden, echoing other liberals, said that its author, Thomas Jefferson, didn’t live up to the ideals of human freedom because he owned slaves.

Jefferson: The Protagonist of Individual Freedom

The crux of Jefferson’s contribution for America rests on the idea of individual liberty, which eventually led to the Bill of Rights (the first Ten Amendments to the US Constitution).

On 20 December 1787, in a letter to James Madison—recognised as the Father of the US Constitution who then became America’s fourth president—Jefferson stated:

‘[A] bill of Rights is what people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference.’

Initially, the Constitution did not detail what American citizens were or were not entitled to under law. Jefferson’s push for a bill of rights was in response to the deliberate omission in the Constitution that potentially hindered Americans’ exercise of the unalienable rights of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. Anti-Federalists, such as Virginia Governor Patrick Henry passionately believed that the Constitution granted so much power to the new federal government that amending the Constitution so as to have a bill of rights was necessary ‘to protect citizens from potentially despotic rulers,’ especially in areas of religious freedom, defence against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the right to trial by jury.

Federalists claimed any such amendments were unnecessary since the Constitution did not repeal these rights declared in state constitutions. The dilemma was that a number of state constitutions and declarations of rights failed to include fundamental protections for citizens—six of the thirteen states had no bill of rights, and none had a comprehensive list of guarantees.

Jefferson said he was ‘captivated’ by what the Constitutional delegates to the convention called the ‘partly national, partly federal’ compromise

Jefferson, who was serving in Paris as Ambassador to France while the Constitutional Convention was taking place, received from James Madison a copy of the newly signed Constitution in October 1787. In his reply to Madison, written toward the end of December the same year, Jefferson said he was ‘captivated’ by what the Constitutional delegates to the convention called the ‘partly national, partly federal’ compromise. Jefferson was concerned that the commission responsible for adapting a bill of rights would not meet the demands of the People. He mentioned six rights that ought to be ratified ‘clearly and without sophisms: freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies, the eternal and unremitting force of the habeas corpus law, and trials by jury.’

Jefferson’s defence of individual rights was based on the Lockean philosophy of the human person’s natural right to reason and to (absolute) ownership of land—this was a dilemma in John Locke’s England since the Crown was the sole proprietor of all lands in Britain—it still is to the present day.

The individual’s right to property, according to Locke (and eventually Jefferson) was ultimately based on Holy Writ:

‘So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground. Then God said: “I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food.’” (Genesis 1: 28-29)

This is the reason why Jefferson stipulated that our unalienable rights of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness were endowed to us by our Creator. The Bill of Rights, therefore, became intertwined with his defence of a republican government, i.e., a self-governing polity that is free from a single despotic ruler and/or a ruling aristocracy whereby the human person is free to live according to the design of the natural order of things.

Jefferson’s Clear Opposition to Slavery

Biden’s argument, criticising America’s third president for owning slaves, is trivial at best, since he never purchased slaves and his positions on slavery underwent several stages of evolution.

In direct contrast, Jarrett Stepman, in his 2019 publication titled The War on History: The Conspiracy to Rewrite America’s Past, said Americans (and Westerners) ‘have lost touch with the immense accomplishments of this venerated American whose greatest fault is that he dared criticize an institution as old as mankind while failing to extinguish it within a single generation.’

Jefferson, in fact, always spoke out against institutional slavery throughout his political career. For example:

- In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), he nailed down: ‘The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other.’

- In his letter to Brissot de Warville dated 11 February 1788, Jefferson wrote: ‘You know that nobody wishes more ardently to see an abolition not only of the trade but of the condition of slavery: and certainly nobody will be more willing to encounter every sacrifice for that object.’

Jefferson not only condemned institutional slavery, but he took actions against it:

- in 1783 he submitted a bill to Congress that would have freed all slaves by 1800;

- in 1807, during his second term as President, he signed into legislation eliminating the Atlantic slave trade, which effectively outlawed the importation of African slaves into the United States. Although it did not end slavery, this significant piece of legislation highlighted Jefferson’s opposition to slavery.

The question remains, if Thomas Jefferson was against the practice of slavery, why did he not free his slaves?

Under Virginia statutes, since slaves were considered property, creditors could seize them from their debtors to satisfy debts

In his New York Times Bestseller The Jefferson Lies, David Barton mentions that while George Washington liberated his slaves on his death in 1799, the law of Virginia prevented Jefferson from doing the same. Jefferson, his parents and his father-in-law had amassed massive debts after the American Revolution, which at his death stood at $107,000 ($2 million in today’s dollars). Under Virginia statutes, since slaves were considered property, creditors could seize them from their debtors to satisfy debts. This is why he capitalised on the increasing number and value of his slaves to achieve two things—increase his access to capital, and protect his slaves from being sold.

It is true that in his utopian mindset, Jefferson thought that deporting black Americans to Sierra Leone, for example, would provide them with a sovereign and independent land of their own. His rationale was that ‘spreading the institution to the West would increase the number of taxpayers, who would cover the costs of the deportation. ’

Jefferson, nevertheless, remained relatively silent on the issue towards the end of his life. Author M. Andrew Holowchak explains that his reluctance to continue to tackle slavery was ‘because of his belief that to act then would be to act before the time was ripe for appropriate action. Action on slavery at the wrong time might result in more harm—that is separation of the union [which eventually happened]—than good.’

The fact of the matter remains that not only did Jefferson despise slavery, he foretold that America would pay a dear price—the Civil War—for the institution of slavery:

‘I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever: that, considering numbers, nature, and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation, is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest. ’

To categorise Jefferson as an oppressor of an enslaved people, as the left continues to depict him, is both mendacious and unmerited. Notwithstanding his shortcomings, something we all have, Jefferson should be perpetually honoured, for he was the architect of the most fundamental rights contained in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: freedom of speech and peaceful assembly, as well as the freedom to exercise religion.