This article by Anita Farkas was originally published in the Hungarian Chronicle in 2021.

Few people know that the global analogue revolution started in the world of comic books. Free Comic Book Day, organized overseas since 2002, has once again drawn crowds to comic book stores, which had become increasingly unprofitable at the turn of the millennium, and that was where record stores got the idea for the Record Store Day and similar events, in a conscious effort to (re)popularize vinyl culture. Publication of the latest work by Attila Futaki, a comic book artist of international fame, is an important domestic event. Created in collaboration with writer Gábor Tallai, it presents the life and era of Puskás Öcsi, making it a great addition to the excitement of the European Football Championship.

After Budapest Angyala (The Angel of Budapest), published in 2017, which commemorated the heroism of the youth of Budapest in 1956, the Public Foundation for Research on Central and Eastern European History and Society has recently presented a comic book themed around another chapter of Hungarian history. For its execution, Gábor Tallai and Attila Futaki, the co-authors of the previous publication, were commissioned, and the seasoned writer–graphic-artist duo created 10 – A Puskás (10 – Puskás), a very special album indeed.

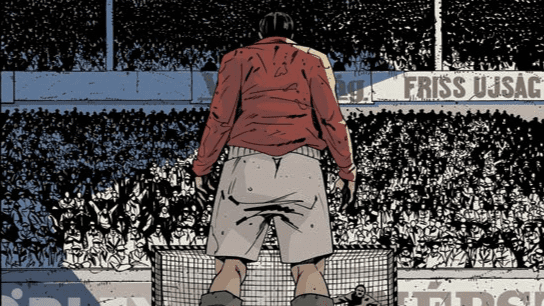

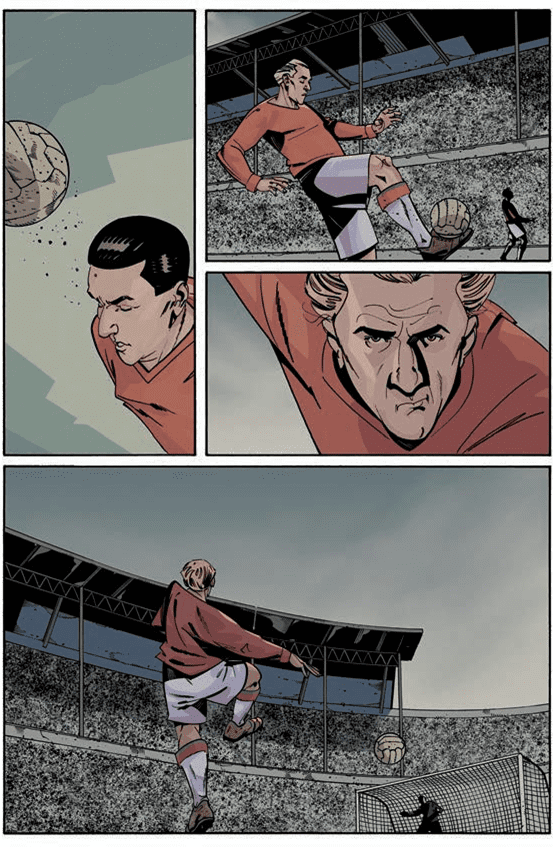

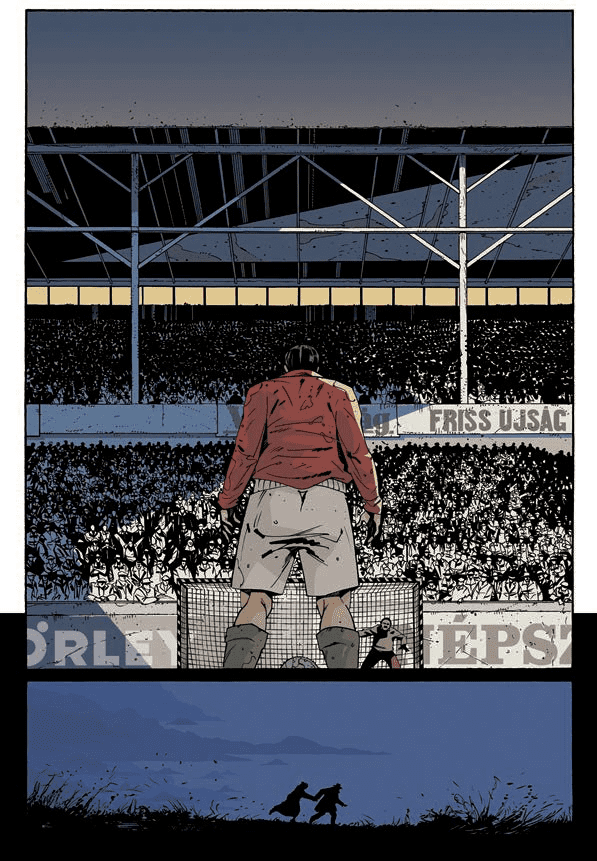

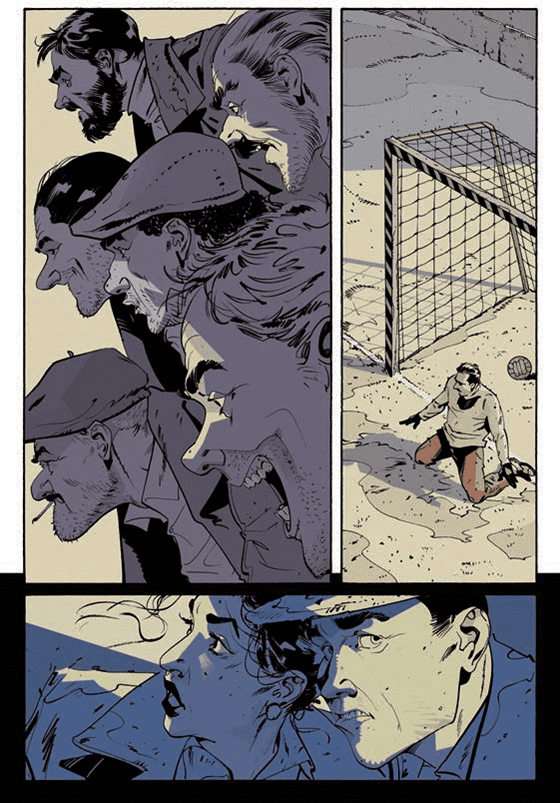

Nothing in this genre has been published about the legendary captain of the Golden Team (better known as the Mighty Magyars outside Hungary) before, but this extensive and detailed new comic book now explores his life and career in sport with textual and graphic humour leaning towards the ironic. In the background, the constrained everyday life in then contemporary Hungary emerges, with Mátyás Rákosi as the symbol of dictatorship, and Sándor Szűcs, the footballer who played in the national team nineteen times and was sentenced to death at a show trial and was executed in 1951, as a representative of the victims. As a result of combining factual events and the artist’s imagination, the book will enthral each generation with different layers, with its period language and clear phrasing, supported by the characteristic style of Futaki: the slightly dark Eastern European blue-grey colours are complemented with a vivid red, evoking the grim period of communism as well as the shirts of the Hungarian national team.

‘The number 10 is full of mystery and power. If you wear the number 10, you were born under a lucky star. The wheel of fortune is forever turning, but this does not mean that sometimes you have it and sometimes you don’t. It means you are destined to fall. But when you stand up again, it is true ascension.’

‘Futaki bravely experimented with overwriting reality with his own visual approach’

The milestones in Puskás’s life and the events unfolding directly around him are, of course, the main lines in the book, but since the story is ultimately fictional, imagined episodes and made-up characters—symbolic, if you like—also appear as typical features of the period. One such character, for instance, is the head coach, nicknamed Gróf [Count], who was stitched together by the writer from different personalities from the golden age of Hungarian football which is still yearned for today; he teaches Puskás and Bozsik, inseparable friends, how to play football when they are just kids. Evoking other members of the Golden Team and a couple of other key matches for Puskás, and not only in Hungarian colours, are also key elements. The absolute culmination of the story, apart from the 6:3 Hungarian victory over England in 1953, is the European Cup final in Glasgow in 1960, where the Real Madrid player with the number 10 on his shirt, cheered by the crowd as Pancho, scored four goals against Eintracht Frankfurt, a feat that has not been repeated at such a prestige match to this day. Behind this accomplishment, the Hungarian heart would also perceive the motivation to get even for our defeat by Germany at the 1954 world championship final.

‘There are lots of great people, but only a few of them are likeable’

The Creators of 10 – Puskás expressly sought to avoid giving us a ‘football comic’ that would only be understood and appreciated by hard-core fans. Gábor Tallai was also interested in the human side of the story, especially the question of why Puskás left Hungary when he was worshipped by the entire country as a star and lived with his wife in an exemplary marriage. Looking for the drama behind the shower of goals, Tallai did find an adequate answer, also emphasized in the book. Puskás’s life reached its nadir in 1956, when his passion for life seemed lost, he gained quite a few extra kilos, and as an athlete he knew he had to do something quickly to avoid being floored psychologically. Therefore, instead of making peace with and becoming the face of the Kádár regime which replaced that of Rákosi, he jumped into the unknown without any guarantee that he would be able to climb back to the top or that after his ‘desertion’ he would ever be allowed to return to his country.

‘One of the worst traits of communists is that they tend to keep their promises. At the request of the comrades, FIFA banned the thirty-year-old Puskás from playing for eighteen months. He did not give up, though. It took him a few weeks to lose weight, he started to train again, and was soon back in top form. As a Real Madrid player he was celebrated as top scorer many times, but his fans did not cheer him as “Öcsi”, but as “Pancho”, his new Spanish nickname,’ we can read in the book. He spent almost ten years at one of the best clubs in the world, and subsequently also collected a number of trophies as a coach. All this was due, according to Gábor Tallai, to two things: God and his own personality—there are lots of great people, but only a few of them are likeable.

To find a fitting visual representation of the likeable rascal was quite a challenge. Attila Futaki, who previously worked for Disney, the American GQ magazine, and The New York Times, believes it is always problematic when it is not a fictional character but an emblematic, widely known person who has to be rendered, together with the environment, in an easily recognizable manner but keeping one’s unique style. Puskás Öcsi is especially difficult to draw, as people would like to see the handsome guy with the wicked smile they have stored in their head on paper, and not someone the artist envisions. It is a bit like when we first read a book, and seeing the film adaptation of it we are disappointed with the cast.

The long struggle with Puskás’s characteristic half-smile was, fortunately, concluded in victory. After many sketches and trials, Attila Futaki realized that by gently turning up the line of the mouth, the image of Puskás with his half-smile in the collective consciousness can be preserved even in the more dramatic scenes. At other times he bravely experimented with overwriting reality with his own visual approach. For instance, when he first drew Dynamo Stadium in Moscow, the site of the ‘friendly’ Soviet–Hungarian match of May 1952, he showed blocks of flats as a backdrop. From archive pictures received from the House of Terror Museum in Budapest, it turned out that the arena was in fact surrounded by empty fields, and there was no floodlighting, either. Futaki, however, did not want these glorious scenes to appear so barren, and finally decided to ‘install’ lights and ‘build’ factories in the neighbourhood…

A visual world elaborated with this level of precision, deftly balancing on the boundary of fiction and reality, is not only typical of the drawings, but of the design of the hard-cover edition as well. Especially because the soon-to-be-published English version of 10 – Puskás, just like Puskás in his time, is destined to win the hearts of the international public, and its co-authors hope it will also become a favourite in France and Italy.

Related articles: