One of the features that make state-socialist or communist planned economies structurally different from free market economies is their diverging ownership structures. While in planned economies the state is omnipresent and it owns the vast majority of firms, factories, houses and capital stock in the country (around 90–95 per cent), in market economies ownership of capital is more dispersed in the hands of private individuals and companies and the state owns only around 15–30 per cent of all capital. One of the most important—and most debated—policies of the regime change of 1989 was privatization, which aimed to reduce the state’s massive ownership by transferring entitlements to the general population.

One of the unique features of Hungarian welfare socialism was that privatization started even before the state-socialist regime collapsed. From the 1980s on there was a so-called ‘spontaneous privatization’ going on in Hungary.[1] Due to this ‘spontaneous privatization’ by 1989, when the transition started, Hungary was ahead of most of the other Eastern Bloc countries in establishing a capitalist free market economy and the corresponding ownership structure. This (unregulated) privatization model also attracted foreign ownership, which meant injecting know-how and expertise into the Hungarian economy which lacked competitiveness in the global economy. On the other hand, the process was not transparent, giving rise to many ethical questions about how the new owners earned their fortune and what connections they might have had with the previous regime. The privatization which benefited ‘insiders’ is also known as the ‘nomenklatura privatization’, and it is one of the most debated processes of the transition.

By the mid-1990s 70 per cent of all formally state-owned houses were sold to private owners

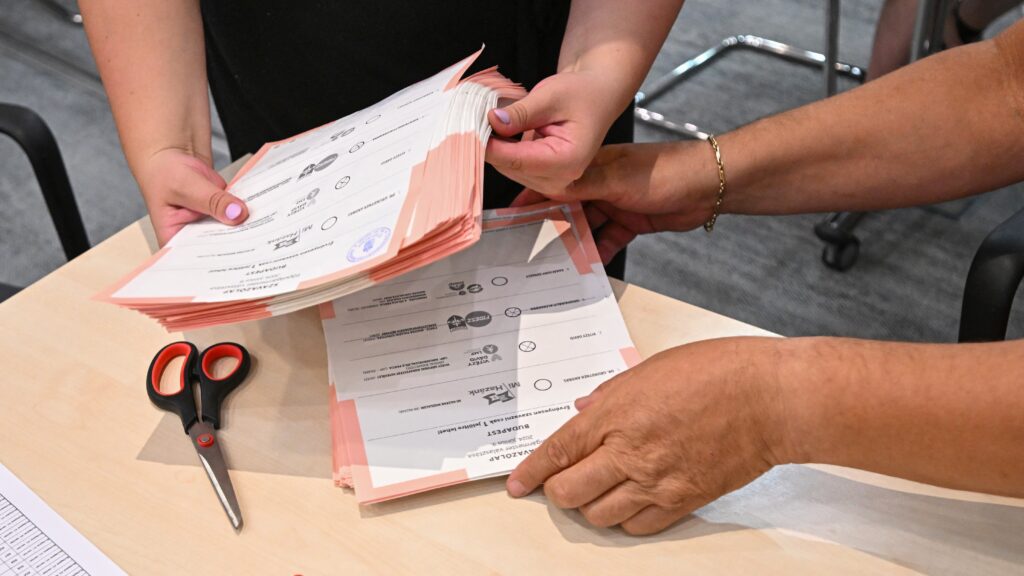

With the start of the transition, privatization was regulated, and it was also extended to all segments of the economy, including housing. In terms of house ownership in Budapest 61 per cent of all the houses were owned by the state before the collapse of the regime. The privatization policy of the 1990s aimed to make the sitting tenants owners of their rented flats, by offering 70–90 per cent discounts on the price of the houses and flats. According to the Housing Act of 1994, local governments could resist selling flats only if the house was in a very bad condition or it was put on an architectural heritage protection list. By the mid-1990s 70 per cent of all formally state-owned houses were sold to private owners.[2] While property privatization made many Hungarians owners of the places they lived in, which was a positive development, the process also raised some ethical concerns. Since during the state-socialist period housing was allocated based on ‘political merit’, the transitionary policies effectively enabled the previous elite to purchase (below the market price) better quality housing, contributing both to the survival of the previous regime’s elite as well as to inequality post-transition.[3]

Parallel to the restructuring of home ownership, the ownership transformation of enterprises was taking place. Before the fall of Communism practically all businesses were owned by the state; only small, usually family-run private businesses were allowed in Hungary. In the whole of the transition region privatization of businesses created a widely exploited opportunity for the politically well-connected to hoard up wealth by purchasing formally state-owned enterprises at a reduced price. In the post-Soviet space, especially in Ukraine and in Russia the privatization of the heavy industry, the natural resource as well as banking sector hugely contributed to the emergence of oligarchs. While the opportunity for corruption arose in Hungary too during enterprise privatization, the Hungarian process was not as misused as in the post-Soviet space. In Hungary privatization of firms was regulated from 1991 onward, and the process was happening on a case-by-case basis (it enabled somewhat more transparency). In Hungary no preference was given to former workers to buy the factories they used to work in, in most of the cases the new owners became either the management or foreign businessmen. In other parts of the post-Communist sphere, like in Romania, voucher privatization was more common, which resulted in dispersed ownership and more worker buyouts.

Foreign businessmen had both the capital and expertise to buy and run businesses in the freshly democratized Central East

A further puzzling question with regards to the 1990s privatization was how to handle foreign buyers. The region was very poor at the beginning of the transition, so it was rare that entrepreneurial-minded individuals had the capital to purchase businesses from the state. On the other hand, foreign businessmen had both the capital and expertise to buy and run businesses in the freshly democratized Central East. While data show that foreign owners were the most successful in increasing productivity and wages, governments in the transition region were worried to offer a huge share of the national economy to foreigners.[4] Strategically, selling domestic assets mostly to foreign owners could have caused an unhealthy dependency on foreign countries and investment, so in most transition countries bids which were opened up for foreigners were limited. In Hungary around 17 per cent of the privatized enterprises got foreign owners, in Romania around 7 per cent while in Ukraine only 1 per cent[5].

Overall, privatization has a bad name in the region as it is widely associated with corruption, and the rescue of the former elite into the new, democratic structures. However, it must not be forgotten, that it was a necessarily process to establish functioning free market economies in the region.

[1]Kálmán, Mizsei, ’Privatisation in Eastern Europe: A Comparative Study of Poland and Hungary’, Soviet Studies, 44/2, (1992), 293.

[2]Alan Murie, Iván Tosics, Manuel Aalbers, Richard Sendi and Barbara Černič Mali, ’Privatisation and after’, Policy Press Scholarship Online, (2012), 3.

[3]Alan Murie, Iván Tosics, Manuel Aalbers, Richard Sendi and Barbara Černič Mali, ’Privatisation and after’, Policy Press Scholarship Online, (2012), 6.

[4] J. David Brown, John S. Earle and Almos Telegdy, ’Employment and Wage Effects of Privatisation: Evidence from Hungary, Romania, Russia and Ukraine’, The Economic Journal, 120, (2009), 686.

[5] J. David Brown, John S. Earle and Almos Telegdy, ’Employment and Wage Effects of Privatisation: Evidence from Hungary, Romania, Russia and Ukraine’, The Economic Journal, 120, (2009), 691.