Born to an Egyptian father and a Hungarian mother, dividing his childhood summer holidays between the two countries, Ahmed Moussa (34) developed a keen interest in everything Hungarian early on. The interest grew into a passion with time, and Ahmed took up folk dancing as a profession. But he always felt that tradition needed to be translated into something truly contemporary and vibrant to appeal to people and arouse their interest in their own culture.

***

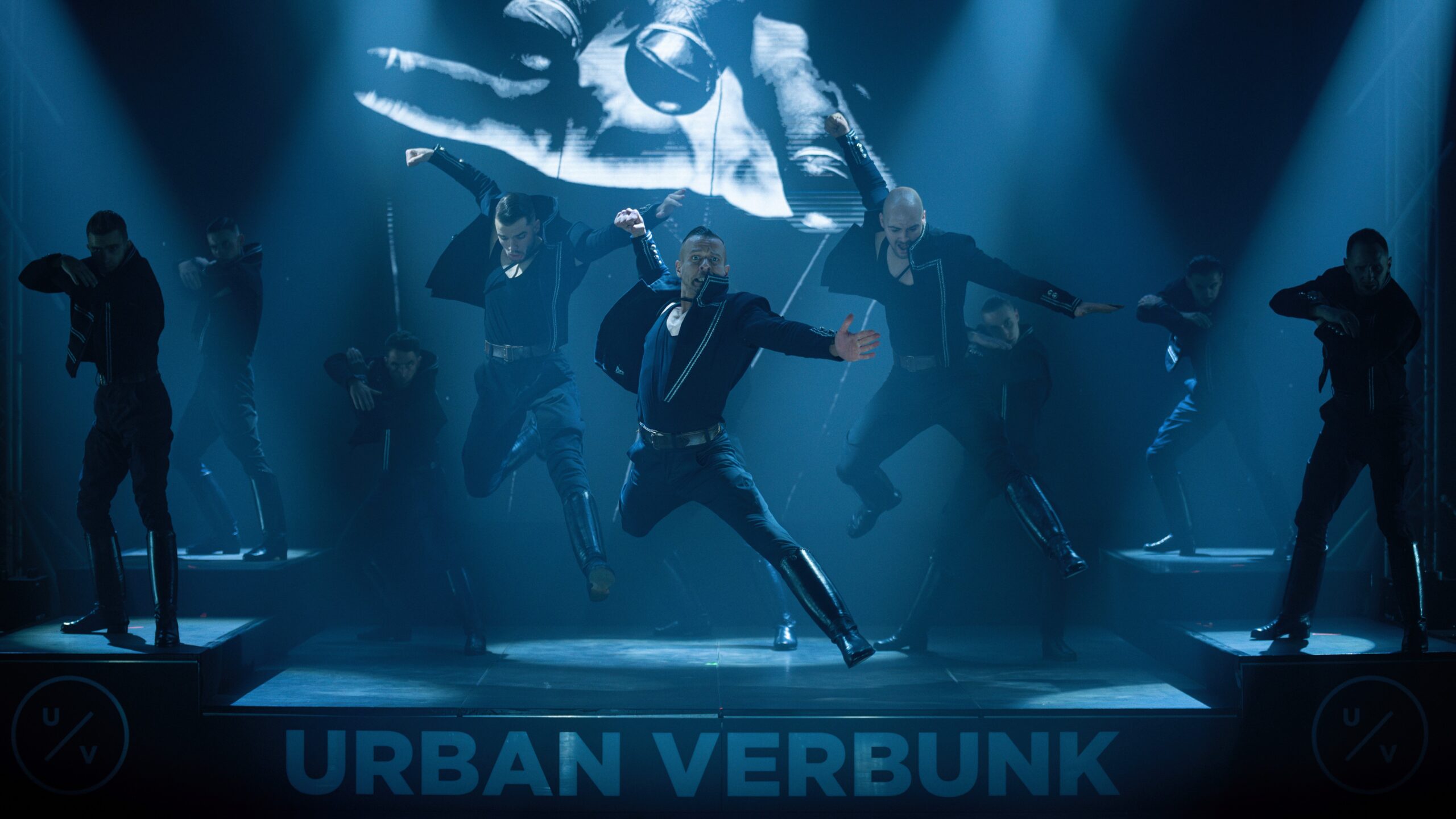

Ahmed Moussa, married and father of a baby boy, leads an all-male dance ensemble that has distinguished itself from other similar formations by bravely merging folk and pop, art and sheer physical prowess, projecting masculinity in the best sense of the word.

Speaking to Hungarian Conservative, Ahmed shares that Urban Verbunk has been around since 2018. ‘In Hungary not that many people are aware that we exist,’ he says, when I confess that I have only recently come across one of their stunning videos on social media.

‘We are folk dancers. We dance our own culture at the mother tongue level,’ Ahmed states.

The type of forceful dancing they do requires extreme physical fitness, equal to that of a professional athlete. ‘The progressive folk dancing that we pursue is very much based on physical strength. We work out eight hours every day. When football players come to our 90-minute shows, during which we hardly ever leave the stage, they are shocked and tell us: “You have danced the equivalent of a football match, only there was no half-time break.”’

When I ask Ahmed about the name they chose for the ensemble, he explains that it is not that they only dance the Verbunk(os), a Hungarian dance and music genre going back to Habsburg-ruled 18th century Hungary. The dance was used to appeal to young men and lure them into the army during the recruiting of volunteers. (The word Verbunk itself is in fact of German origin, the Hungarianized version of Werbung, meaning recruitment.) The Csárdás is perhaps better known as a typical Hungarian dance, Ahmed remarks, but they did not opt for it as it is danced with women, while Verbunk is a purely male dance. There is obviously no need to explain the part Urban of the name: it highlights the fact that they are offering a modernized version of a traditional Hungarian folk art genre, placed in a contemporary, urban setting.

The members of the ensemble are all professional, full-time dancers. But at one point they felt frustration growing that what they do reaches relatively few people, as their mission is not just to spread awareness and enthusiasm about Hungarian folk culture at home (which, he surprisingly claims, is very much needed, as the average person is losing touch with their heritage), but abroad, too.

Although they regularly perform at one of Budapest’s premier dance theatre venues, RaM – Art (formerly RAM Colosseum), they felt the best way to reach a broader audience is to combine the strengths of social media with direct, personal contact.

‘We decided to take our art out onto the streets, and dance right among the people,’ Ahmed explains. When I ask him to estimate the impact of their videos, he tells me that the recordings of their flashmobs have absolutely record views in Hungary, comparable to those of the top influencers. But they also stand out in European terms as well.

‘Our videos have at least one million views and 50,000 likes on Instagram. And we have 250,000 followers, only on that platform.’

Dancing and popularizing Hungarian culture is clearly more than a job for Ahmed and his troupe members: it is a vocation. When I ask him if one can make a proper living doing what they do, he ponders his answer for a few seconds. ‘This is not just about making a living, it is about making a huge operation work, with tens of millions of forints in expenses each month, with several people, not just the dancers, on the payroll. It is not easy to stay afloat,’ he says, but adds: ‘We receive quite a lot of support from the Hungarian government, maybe more than other dance troupes, but I think we also commit to doing more.’

But it took them four or five years before they got any grants or found any sponsors, Ahmed recalls, but by that time they had developed their unique, market niche ‘product’ that started to attract more funding.

But it is not all nice and dandy, he remarks, stressing that what they have embarked on is often risky and difficult. ‘We are not the most popular with our competitors in the art world, because what we do is unusual and different,’ he adds. But they get a lot of love from the people, who recognize them in the street, and congratulate them on what they do.

Interestingly, however, three quarters of their audience is foreign. It is not that they do not target Hungarians, it’s that foreigners seem to be often more receptive to what Urban Verbunk does. ‘I think it is great that we as promoters of Hungarian folk dancing are followed by Ukrainians, Russians, Chinese, Arabs, Americans,’ he stresses.

In fact, Urban Verbunk has just qualified for the finals of the Arabs Got Talent show, the second largest of all Got Talents in the world (only second to the Indian one, Ahmed notes), which knows no country boundaries, but caters to Arabs all around the world, from Egypt to Lebanon. They also did a flashmob in Saudi Arabia, ‘a country that only five years ago still did not allow tourists in,’ Ahmed notes, adding that when they started dancing in the streets, people looked at them amazed, and asked them where they were from. It turned out people had never heard of Hungary, but most immediately checked the country out on Google Maps on their smart phones. People also asked what Verbunk was, and Ahmed could respond that it is for Hungarians what dabke is for Arabs. So, I suggest, Urban Verbunk is also building Hungary’s image abroad, to which he replies: ‘Well, perhaps many would not see it that way, but I think we are.’

As far as their plans are concerned, UrbanVerbunk was to perform in Germany at the beginning of December (Note: the interview was recorded at the end of November), and they are going to take part in the Britain’s Got Talent show in January. ‘I think we are in a phase of organically building our brand that few other Hungarian ensembles have managed to reach,’ he asserts proudly.

The management of Urban Verbunk is now working on getting the troupe into America’s Got Talent. When I ask Ahmed if they have ever performed in the United States, he says: ‘No, not yet. But we would very much like to.’