The following is a translation of an article written by Gáspár Kéri, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

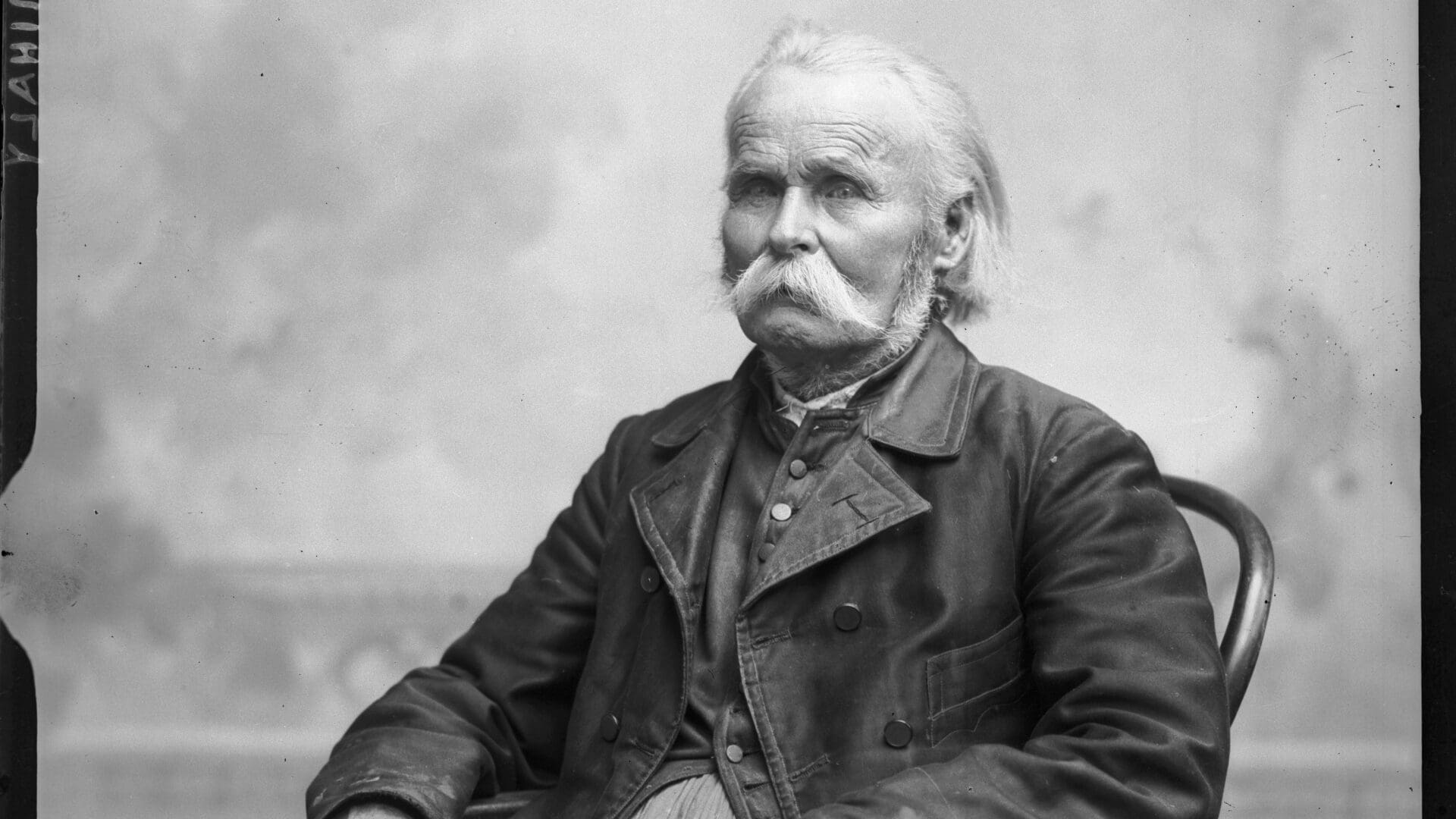

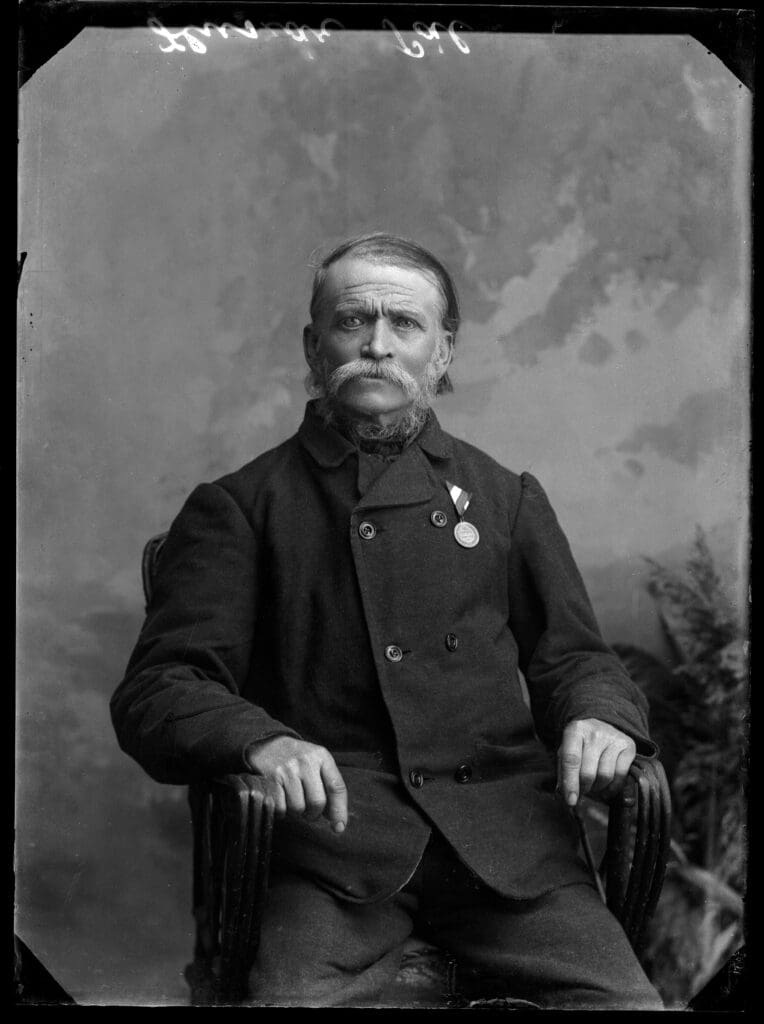

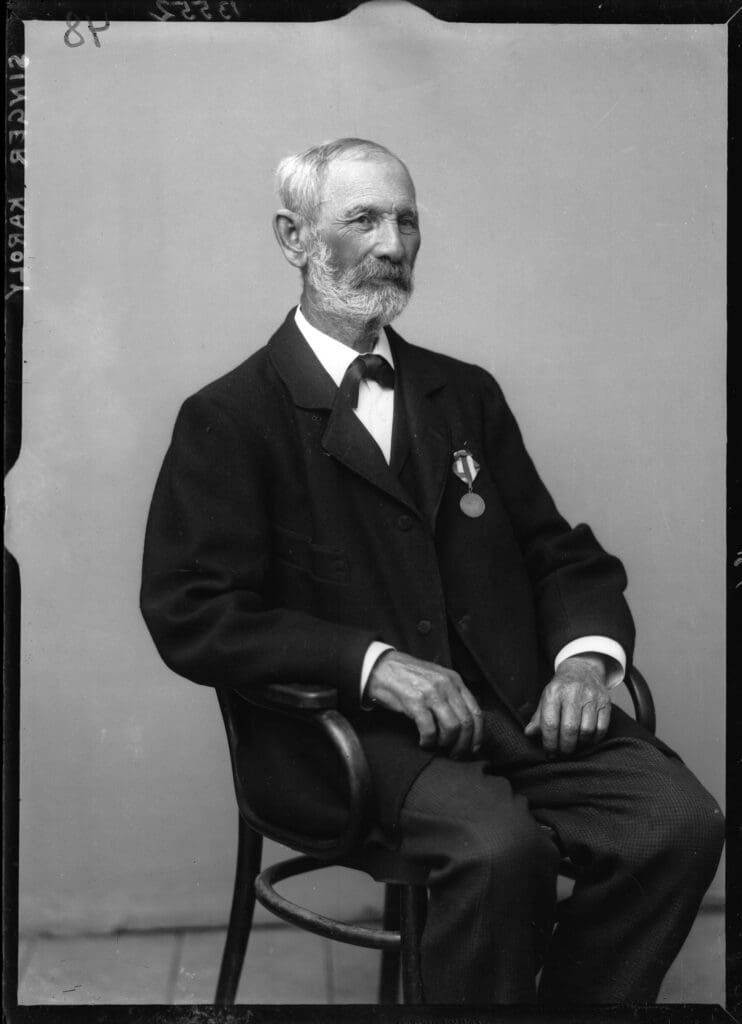

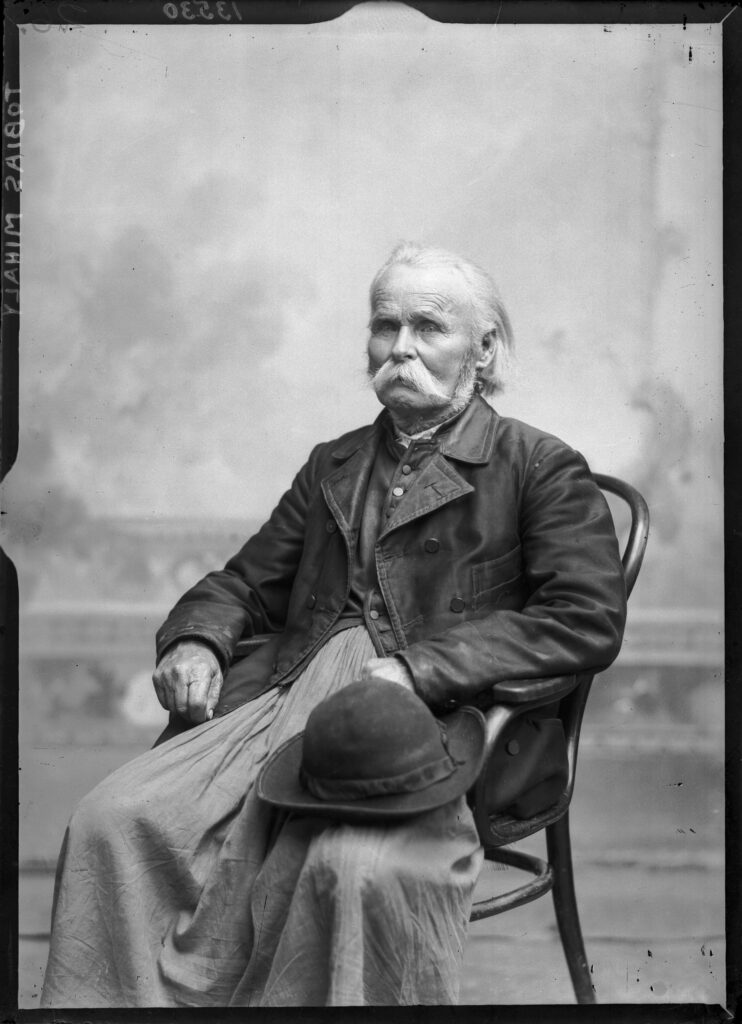

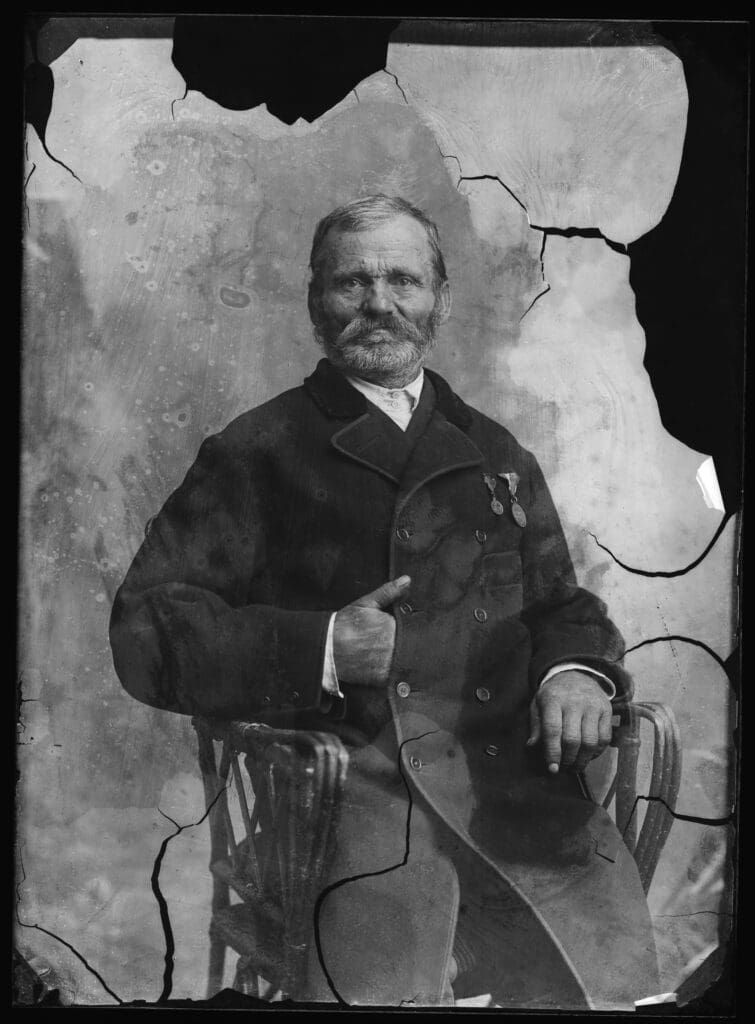

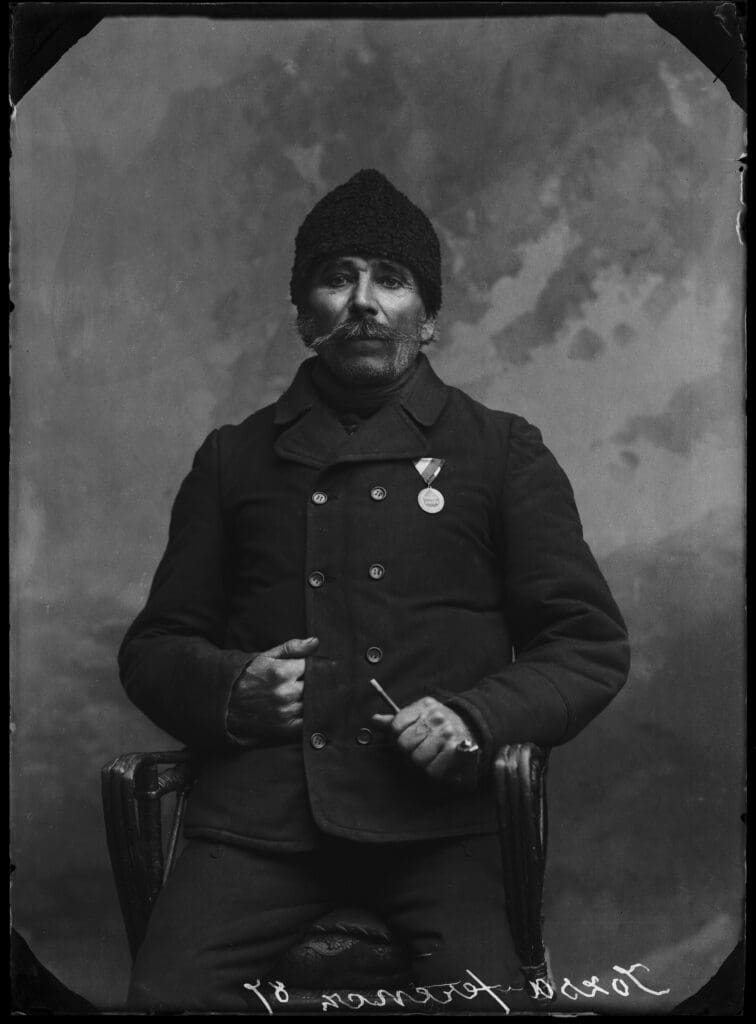

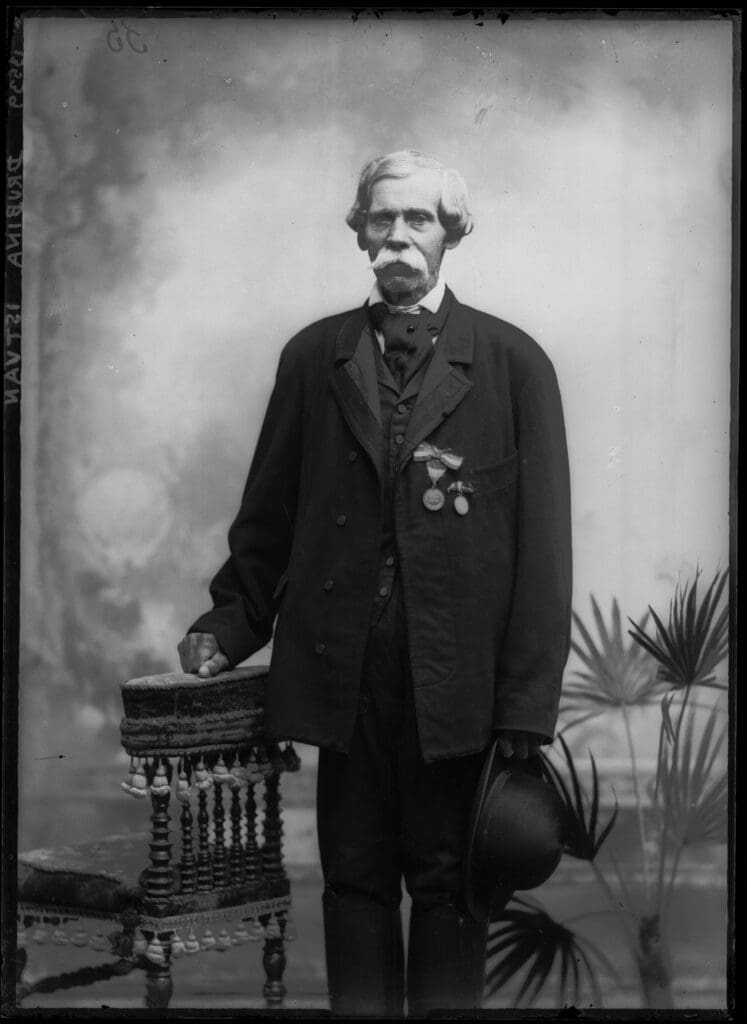

Looking at the portraits of 1848 soldiers by József Plohn, a photographer from the city of Hódmezővásárhely, the past comes to life before our eyes, with the collection creating an extraordinary monument to the Hungarian freedom movement of the 19th century.

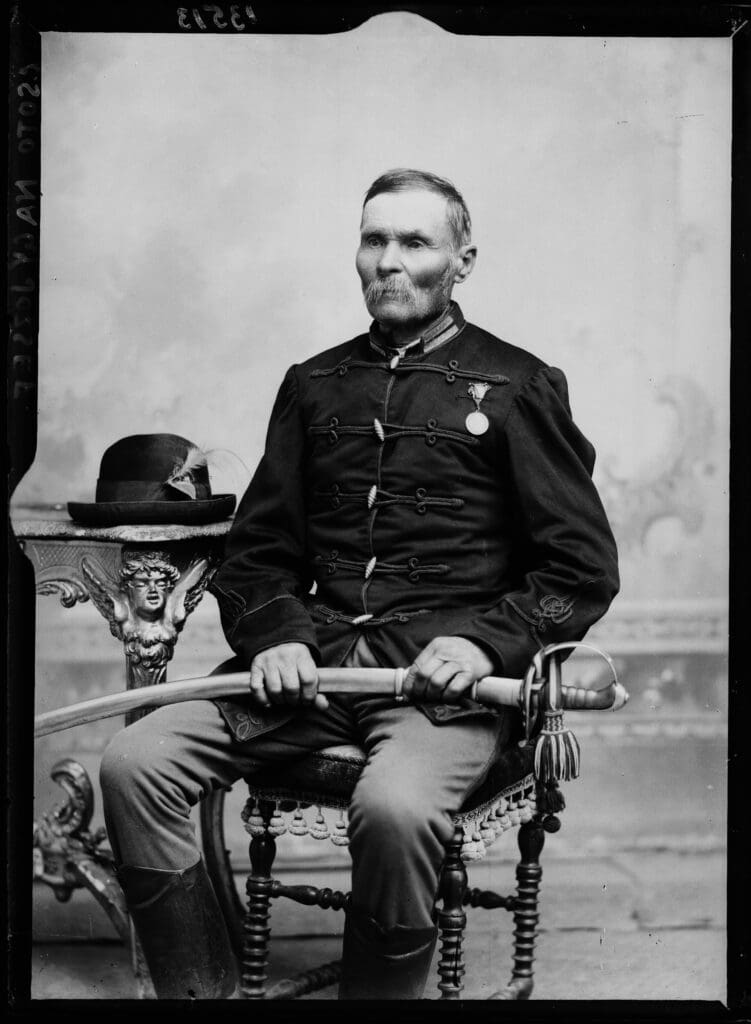

Old-aged men from the Great Hungarian Plain standing or sitting straight up face the camera and indirectly us, the viewers of these portraits today. What was previously only known from history books and clichéd speeches at the 15 March commemorations becomes, when seeing these pictures, the unvarnished truth, a gesture of an encounter with the past. The Local History Collection of the János Tornyai Museum in Hódmezővásárhely has photographs—glass negatives and paper copies—of one hundred and fifty Hungarian soldiers of 1848. They visited the photo studio of József Plohn in the twilight of their lives to have their faces captured in photosensitive emulsion

and become part of collective Hungarian memory forever.

The antecedent of the story was the nationwide collection of photographs initiated by the Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca, Romania) National Museum of Historical Relics with its call for Photographs of the War of Independence for the Millennium, dated 15 March 1894. In its advertisements published in newspapers the institution encouraged all defence associations, photographers, and individuals to take photos of the artifacts, battlefields, and graves of the Hungarian Revolution, and not least of the surviving former soldiers. Almost the whole country was mobilized and began research to create a large-scale exhibition planned for the Millennium to commemorate the freedom fight in a truly dignified way, using photography, the youngest medium of image-making at the time.

‘The clothing, posture, and distinctions of the soldiers are revealed as genuine attributes in the photographs’

Recent research suggests that József Plohn took the first group of his photographs in 1894–1895 on behalf of the Hódmezővásárhely Defence Association. The photographer was already a respected citizen of the town and had professional and friendly relations with the painters of the Great Plain. In addition to cabinet portraits, which were fashionable at the time, Plohn also took ethnographic and anthropological photographs of the surrounding local homesteads, their material and architectural monuments, typical moments of peasant occupations, folk costumes, and folk traditions. His legacy, which is of decisive source value, can not only be found in Hódmezővásárhely but also in the Photographic Collection of the Museum of Ethnography. It is a tragedy of Hungarian history that the photographer died in 1944 in a cattle car on his way to Auschwitz.

Plohn took eighty-four photographs of veteran soldiers in the two years preceding the millennium, and in 1902 he continued his work, adding another seventy-two pieces to his collection. Some of his subjects, who had already appeared in earlier photographs, sat down in front of his camera again, so today we have a total of one hundred and fifty-six portraits of this kind. Although similar photos of elderly soldiers were taken all over the country at the time, nowhere else is such uniform typology and visual appearance to be found, and nowhere else is the social stratification of this part of the Great Plain of the time so eloquently illustrated. Nevertheless, the photographs can be distinguished visually quite clearly according to the date of their creation: in the 1894–1895 portraits, we see half-figures sitting in armchairs in front of a homogeneous background, while in the 1902 portraits, the full-length photographs of veterans are often surrounded by studio props—plants, furniture, and characteristic painted backgrounds.

The elderly people in the photographs had been mainly recruited from poor peasant backgrounds during the War of Independence, and several factors influenced their post-revolutionary fate. Their clothing, posture, and distinctions, the traces of their half-century of life, are revealed in the photographs as genuine attributes. Some of them went into hiding after the defeat of the freedom fight, some were conscripted into the Austrian army, while others joined the Hungarian Legion in Italy. Later, after the Austrian–Hungarian Compromise of 1867, almost all of them returned to their native land, where they lived in modest or fair financial conditions, as day labourers, farmers, or simple townspeople. The political climate of the time is reflected in the fact that most of them wear a Veteran Medal, but there are some who had even served in the Austrian army and thus wore the 50th-anniversary badge of Franz Joseph’s coronation as Emperor.

Today, the names, ranks, and former occupations of ninety of the soldiers in Plohn’s photographs are known, and in many cases we are familiar with their entire lifepaths. This is partly due to the photographer’s precise notes and partly to the careful research of posterity—the publication of this article was also greatly assisted by the work of historian Ferenc Bernátsky, head of the Local History Collection of the János Tornyai Museum—which has kept these photographs in the spotlight for decades. As a result, from time to time, most recently last year, new descendants have come forward after recognizing their ancestors in the portraits of unknown veterans.

Click here to read the original article.