The war in Ukraine is hungrily ‘consuming’ the manpower of Ukraine and Russia. To tap into new groups with the capability and will to fight, both sides are casting their nets across the globe, recruiting people to fight, either for money or ideals, or both. Through the involvement of foreign nationals, the war has become more global than ever before: the fighting in Eastern Europe now impacts families worldwide, with governments scrambling to deal with the geopolitical fallout and combatting both sides that are expanding their global propaganda.

Volunteers and Mercenaries in European Wars Before WWII

Of course the phenomenon of foreigners voluntarily opting to join one of the sides in a European conflict is not new. For one, many, especially those of Communist convictions, including from Hungary, went to fight in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), to support the Republicans against the Nationalists of General Franco. A few years later, thousands of anti-Communists from Scandinavian countries, the Baltics, and from Hungary flocked to Finland to support the Fins in fighting off the Soviet invasion in the 1939–1940 Winter War.

The French Foreign Legion should also be mentioned here. An elite military force originally consisting of foreign volunteers in the pay of France but now comprising volunteer soldiers from any nation, including France, for service in France and abroad, it was founded in 1831 to allow foreign nationals into the French Army. Its members fought in both WWI and WWII.

The Rise of the Mercenary Industry

In the aftermath of the Cold War, when nation-states seemed to weaken, and the ‘end of history’ was seemingly drawing near, new forms of statecraft were burgeoning. The well-known and mediatized threats of terrorism and crime syndicates aside, the power and capabilities of corporations expanded unprecedentedly. This poured over into the world of warfare as well.

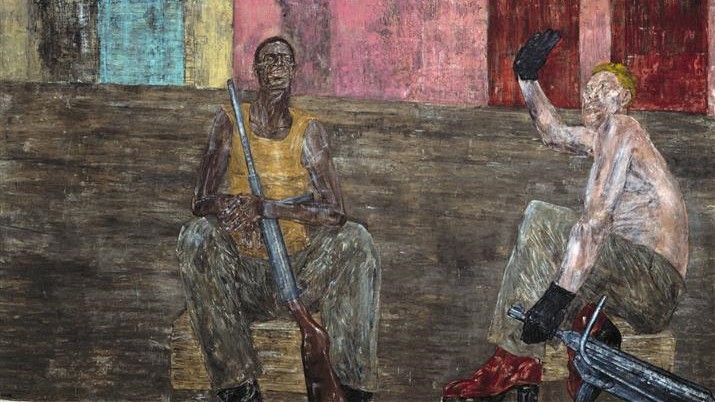

The mercenary industry had reached unprecedented heights by the 2010s. This was a consequence of overlapping processes of the neoliberal world order, all connected to the retreat of the nation-state. Areas with fragile states in the post-colonial world, like Africa, were failing, unable to train and maintain standing armies, especially in the face of accelerating technological development. In turn, many countries, like Eritrea, Ethiopia, and the former Zaire in the late 1990s, tried to recruit Europeans willing to fight for far-away African countries, and at the same time able to operate sophisticated weapon systems, like attack helicopters.

Meanwhile rich and developed states showed less and less willingness to fight wars far away from their shores, let alone reintroduce conscription. The ever-rising shortages of manpower of expeditionary wars of the West like the ones in Iraq and Afghanistan were consequently filled by private contractors. Of course, these men were not the ones who spearheaded offensives, flew fighter planes, and cleared mountain caves of terrorists, but rather people who maintained supply lines, guarded bases, and protected VIP persons from targeted assassinations.

And it is not only classic ‘mercenary companies’ like Blackwater, Control Risks or Executive Outcomes that have thrived and multiplied in the neoliberal era. Men with military training of all kinds became much more mobile, with digital technology and globalized transportation making the travel of people and information even easier. Thus, not only do private companies play a big part in the mercenary/volunteer business, but any given entity that has the money and connections can easily recruit soldiers across the world—that is, if the great powers that can control and shut down communication lines do not object.

Foreigners Fighting in Ukraine

The war in Ukraine follows the tradition of the last thirty years in this sense, too. Both elements that drive the global mobility of military men are observable here. First, while Ukraine is not a weak state in terms of development, it has obvious limits in compelling its population to fight in the war. The manpower limitations of the Ukrainian army have been a topic of scrutiny since 2023. Russia does not have the same level of limitations, but they are still reluctant to overpressure society with repeated requisitions of fighting-age men.

The war quite literally consumes people; they are killed or maimed physically and/or psychologically at an unprecedented rate. The effects of automatic weapons and massed artillery have been well-known since the First World War, when certain units suffered losses of 200 to 300 per cent throughout the war, losing their manpower several times over, filled with replacements just to lose the replacement groups again and again. This carnage seriously scarred the Western mind, but wars have not become less bloody since then. The lack of space for manoeuvre, the limited area of the battlefield, and the ubiquity of sensors helping in targeting just multiply the effects of the intensive use of artillery, automatic weapons of all calibre and types, mines, armoured vehicles, aerial bombing, and now drone swarms, which are obliterating both Russian and Ukrainian manpower at an exorbitant rate.

For both sides, the use of foreign fighters is consequently quite logical. They alleviate domestic pressure to recruit more soldiers, with the new fighters likely being versed in military matters, so there is no need to train them. They also demonstrate the global clout of the given side by showing the diverse coalition that stands behind their effort. Of course, this is a double-edged sword, which is why there is an intense war of narratives, too, about whether these people are mercenaries or volunteers. In the war propaganda of both sides, a mercenary is somebody who does not possess any of the motivations that justify fighting a war—patriotism, human rights, and so on. His presence shows the weakness of the given side, demonstrating that it cannot muster enough popular support for its war effort and depends on the financial power of a small elite to soldier on. A volunteer, on the other hand, is the ideal opposite of all this, fighting for larger goals and taking the ultimate step of going to countries of people they ‘do not even know’. His presence shows the outpouring of global support for the given side.

The Case of Colombian ‘Volunteers’

A fascinating case of the global recruitment of manpower and the propaganda war flaring up over it is the group of Colombian soldiers that are fighting in Ukraine. The South American country has long emitted hundreds of soldiers to fight in foreign wars. It possesses both a huge pool of military trained men, a military establishment with international connections, and the ‘push’ factors of the precarious state of military financing. Colombia has been, on and off, fighting an internal war since the late 1940s, when the great civil war, La Violencia, broke out. By the early 2000s, this war became focused on the confrontation of the government with the FARC and ELN left-wing guerrilla forces. There was a significant troops surge in this last period, with 235,000 active personnel just in the land-based forces, although the number of active-duty soldiers fell to just under 190,000 as of the latest 2024 February edition of the Military Balance database. This has created a huge pool of veterans retiring after active service. while the numbers fell to just under 190,000 as of the latest 2024 February edition of the Military Balance database.

The Colombian army has close ties to Western militaries, too. The army was originally modernized according to the French model in the late 19th century, as were other Southern American militaries, but after World War I, the United States stepped in as the number one partner. Americans, in the spirit of Cold War containment, helped defeat several waves of left-wing insurgency since the 1960s, trained high-level officers and common soldiers alike, helped actively at the height of the drug war in the 1990s, and supplied most of the equipment for decades. While what the networks are is unclear due to the sensitivity of the process, it is a clear pattern that Colombians are recruited mostly by companies and individuals tied to Western military establishments. Grey Dynamics reports that 1,800 Colombian veterans already serve in the armed forces of the Emirates, mostly through the US-affiliated Reflex Response Security. In this context, the presence of Colombians in Ukraine is another sign that the Ukrainians are relying on Western networks for resources, in this case, global recruitment. It is important to note that the Colombian government disapproves of this: Gustavo Petro, like other Latin American heads of state, tries to remain neutral and not throw resources into the European conflict. Still, he cannot stop Colombians from travelling.

The number of Colombians fighting in Ukraine is unknown. The Ukrainians say that at least 2,000 fighters of 52 nationalities are fighting on their side, and the Colombians are considered one of the largest foreign groups. Their role in the public communication of both countries is notable. English language Ukrainian news website Euromaidan Press regularly commemorates recently fallen defenders of the country in groups of four. Just in the last month, two Colombians were mentioned in a post on X, which shows that their role is at least not marginal.

Euromaidan Press on X (formerly Twitter): “We honor the men & women who made the ultimate sacrifice while defending Ukraine in the Russo-Ukrainian war.They will not be forgotten.RIP – Petro Nemesh (39), Serhii Baidalinov, Colombian fighter Apolinar Prada Díaz, Mykhailo Oleksiiv (21)#LetUkraineStrikeBackNoLimits pic.twitter.com/S9lUv1scwm / X”

We honor the men & women who made the ultimate sacrifice while defending Ukraine in the Russo-Ukrainian war.They will not be forgotten.RIP – Petro Nemesh (39), Serhii Baidalinov, Colombian fighter Apolinar Prada Díaz, Mykhailo Oleksiiv (21)#LetUkraineStrikeBackNoLimits pic.twitter.com/S9lUv1scwm

Russian propaganda also highlights Colombians among the Ukrainian foreign fighters; of course, from their viewpoint, they are ‘mercenaries.’ The Russian propaganda channel Track A Merc (Track a mercenary) on Telegram, which seeks to expose foreign fighters by publishing their names and photos, has highlighted at least ten Colombian fighters among other nationalities, reporting several of them being killed or maimed in combat. Pro-Russian sites on X also push narratives of Colombians being used as ‘cannon fodder’ and even write about unconfirmed ‘unrest’ by Colombian soldiers. In X videos sometimes whole small units—several squads or a full platoon—are heard speaking Spanish, as the video below showing soldiers praying in groups allegedly before a battle, speaking with an accent resembling South American Spanish.

Leandro Romão on X (formerly Twitter): “Colombian mercenaries of the Armed Forces of Ukraine pray in Spanish before the next battle with the Russian military.They came to a country that they hardly knew existed before, in order to kill Russians for money. And now they are counting on the help of the Almighty… pic.twitter.com/B36rSydFze / X”

Colombian mercenaries of the Armed Forces of Ukraine pray in Spanish before the next battle with the Russian military.They came to a country that they hardly knew existed before, in order to kill Russians for money. And now they are counting on the help of the Almighty… pic.twitter.com/B36rSydFze

The Colombians have already caused diplomatic fallout, too. Two of them were kidnapped in Caracas by the Venezuelan government while on their way back to Colombia and shipped to Russia to be imprisoned. This caused diplomatic embarrassment for the Colombian government. Still, it also shows that the Russians are at least wary of the involvement of these groups in the war, going a long way to demonstrate their ability to track, catch, and imprison them. Obviously, this does not stop the flow of Colombians into Ukraine.

The presence of Colombians and other foreigners may become even more and more pronounced as Ukraine struggles to maintain troop levels while fighting an intensive war, with the Russian armoured columns doggedly pushing deeper into the Donetsk region. While it shows a weakness on the part of Ukraine, it also demonstrates an important Western strength: tapping into the resources of military communities trained by Western soldiers. That is a resource that few great powers can match, with Western military expertise and connections reaching across the globe. While diplomatically the West could not muster the Global South, it can at least tap into its manpower. Of course, Russia does so, too, bringing in fighters from friendly countries in Latin America. One way or the other, what may appear to be a local conflict leaves hardly anyone uninvolved.