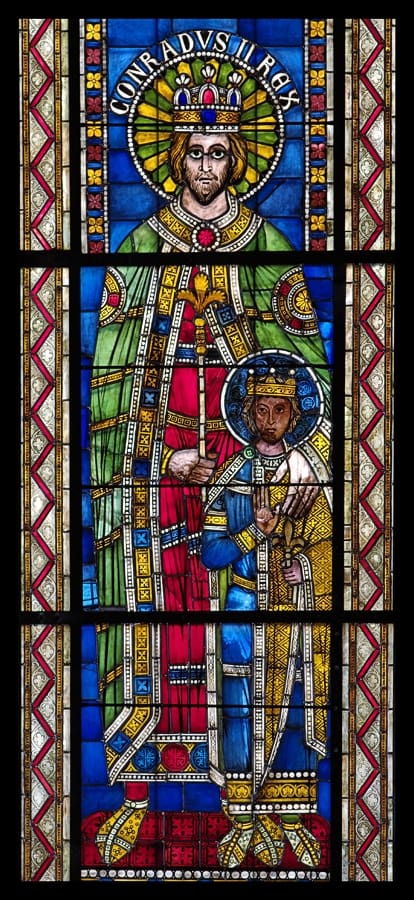

The first decades of the Kingdom of Hungary were defined by the circumstance that King Stephen I (r. 997/1000–1038) was married to Gisela, the sister of the German Emperor, sometime in the late 990s, but perhaps not until after his coronation in 1000. As a result, King Stephen was able to carry out his extensive work of state and church organization free from external attack as long as his brother-in-law Henry II (r. 1002/1014–1024) was the Holy Roman Emperor. Henry inherited the policies of his predecessor, Otto III, who sought to link Polish, Czech, and Hungarian territories to the Empire by spreading Christianity. However, after Henry’s death, the situation changed dramatically during the reign of Conrad II (r. 1024/1027–1039). Not because his great-grandfather was Prince Conrad, who had fallen against the Hungarians at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, but because of rivalries between the nobility of the Hungarian–German borderlands. Conrad believed that the idea of a universalistic Christian realm during the time of Otto III had failed and that he had to prove the Empire’s authority by force of arms. Already during the reign of Henry II, the Polish–German conflict, which led to a long war, was renewed, followed by a Czech–German and then a Hungarian–German clash under Conrad.

The exact cause of the clash was not clear to the German chroniclers of the time. There was certainly a conflict between German and Hungarian interests in Venice, and then also over the question of the succession to the Duchy of Bavaria, since King Stephen’s son, Prince Emeric, could have also claimed the right to the succession through his mother Queen Gisela after Henry II’s death.[1] Tension was further indicated by the fact that in 1027 King Stephen refused to allow a German delegation disguised as pilgrims to Byzantium to pass through his country, although it was led by the Emperor’s envoy, Bishop Werner of Strasbourg. This was followed by border fighting until the German Emperor’s army broke through the western Hungarian border defences in the summer of 1030 and entered the country on both banks of the Danube. Not since the Battle of Pressburg in 907 had the country been attacked to this extent from the west. On the left bank of the river, the advancing troops of the allied Czech Prince captured Pressburg, while the German army on the right bank advanced as far as the Rába. However, the swampy landscape of the Rába and Rábca Rivers, protected by artificial obstacles, made it impossible for the Germans to resupply and halted their advance, thus they were forced to retreat. The Hungarians stayed in their wake and, mentioned for the first time in the sources,

managed to encircle the German army at Vienna and force the Emperor into a humiliating peace treaty.

Wipo, the biographer of Emperor Conrad II, also noted that ‘since the Emperor was not able to enter a kingdom so fortified with rivers and forests, he returned’.[2]

Both Hungarian and German sources report the German defeat in the same way. The earliest legend of King Stephen, canonized in 1083, is the most detailed one: ‘Conrad…destroyed the tranquility of peace…and tried to invade the borders of Pannonia. Against him Stephen consulted bishops and chief lords and drew together the armed men of the whole of Hungary for the protection of the country. First, however, recalling that he could do nothing without Christ’s help, lifting his hand and heart to heaven and commending the injustice [he suffered] to his Lady, Mary the ever Virgin Mother of God.’[3]

Legend has it that the Virgin Mary listened to the King’s prayer and helped him. She did so by calling on the army to retreat when an envoy arrived unexpectedly at the German camp on behalf of the Emperor—the envoy was sent by Mary herself. ‘After the withdrawal of the enemy, the holy man [that is Stephen], knowing himself to be visited by God’s mercy, prostrate on the ground, gave thanks to Christ and His mother, to whose protection he entrusted himself and the rule of the kingdom with persistent prayers…In his turn…the emperor understood that the messenger which caused their return was indeed not his, and that it was done through divine mandate.’[4] Surprisingly, Wipo, in his work The Deeds of Conrad II, completed in 1047, states, in accordance with the Hungarian author’s setting, that ‘King Stephan, whose forces were entirely insufficient to meet the Emperor, relied solely on the guardianship of the Lord, which he sought with prayers and fasts proclaimed through his whole realm’.[5] Wipo suggests that only the heavens could have prevented an otherwise certain German victory. The Hungarian victory surprised everyone. There can be no doubt that it must have been a miracle in military terms. The newly formed kingdom had managed to put to rout and even defeat one of the most powerful armies in Europe at the time, led by the German Emperor himself. Nevertheless, contemporaries saw this as a different kind of miracle.

The modern reader might scoff at the medieval chronicler’s words about divine assistance, even dismiss it as gibberish, as he rather tries to find rational reasons for military victory. This attitude, however, fit in perfectly with medieval thinking, and the protagonists were fully convinced that their success or failure was due to the gaining or lack of heavenly support. To put it quite simply,

they believed in the power of prayer, which for centuries defined the relationship between believers and God.

Surprising as it may sound, not only the Carolingian Dynasty but also the German Ottos and Henry II based their power on prayer as well as arms. The monarchs and their families were the first of the laity to have their names inscribed in the great books of life and to whom special prayers were dedicated. In the course of the church organization in Hungary in the 11th century, Western, largely German converts introduced the country to centuries of Latin church culture. The foundations of this church culture go back to the Carolingian Empire, where the various peoples of almost the whole of Europe were brought together and formed into a single empire through the Latin liturgy and church organization. A sign of this was the copying and distribution of large numbers of liturgical books with corrected and supervised texts among the ecclesiastical centres of the empire.

As part of this deliberately organized ecclesiastical practice, the monks were required to say daily prayers for the monarch, his family, their immediate community, and the whole Christian nation. The need for monastic prayer was clear to monks and rulers alike. This was a prominent function of the ‘royal abbeys’ since prayer was essential for the well-being and salvation of religious communities.

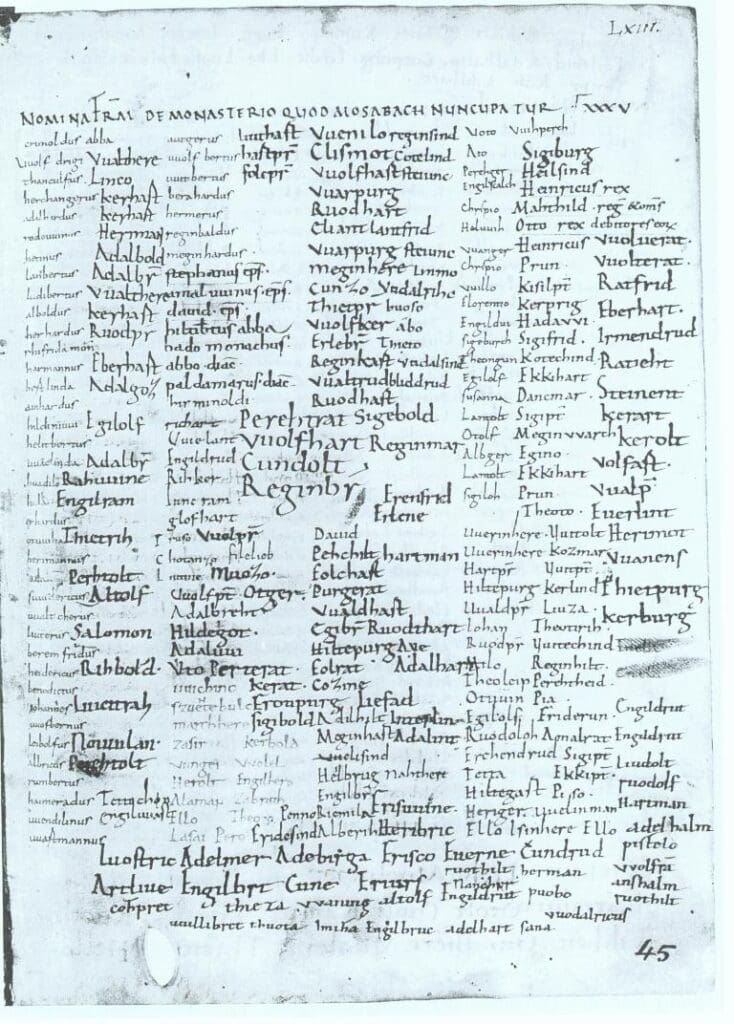

Organizing a commemoration for the dead and the living required a lot of background. From the second half of the 8th century, so-called prayer communions began to emerge, whose members’ names were inscribed in manuscripts known as confraternity books (Book of Life, German Verbrüderungsbuch). The persons named in such books were regularly commemorated in the prayers of the monks, and as a result, a veritable network of prayer was woven around the whole Carolingian Empire. Between 700 and 900 the abbeys became the powerhouses of prayer.[6]

An entry in the contemporary Fulda yearbooks best attests to the functioning of the prayer communion. The year 874 was a disastrous one, with an exceptionally cold winter destroying many people and animals. At the same time, King Louis of Germany had a vision of his father one night, telling him how much he needed the help of prayer to gain eternal life. The stunned King immediately sent a letter to all the abbeys in the empire, asking them to pray to God for his father’s salvation. Finally, the bad winter was also interpreted as a punishment for not praying for the late emperor.

Of all the surviving manuscripts, the one from the German Reichenau is certainly the best known. It was composed at the Reichenau Abbey from the 820s onwards and preserves not only the names of the abbey’s founders and benefactors but also the names of those with close spiritual ties to the abbey, with 164 pages containing over 38 000 names. Some 700 names from the 11th to 12th centuries are known now, including that of King Stephen of Hungary. Abbott Berno of Reichenau (d. 1048), ‘after Stephen had generously helped the Gauls, Germans, and others who were making pilgrimages through his country to Jerusalem and other holy places…, celebrated masses for the spiritual salvation of him and his wife Gisela, and entered both their names in the Book of Life’. The name of the King of Hungary was entered in the confraternity book of St Peter’s Abbey in Salzburg in a similar way. Unfortunately, no similar sources have survived of medieval Hungary.

The Hungarian King certainly believed that the heavens had helped him on the battlefield.

Therefore, it is not unreasonable to trace the Hungarian royal dynasty’s veneration of Mary back to the time of King Stephen. This seems to be borne out by the legend of Stephen and the offering of the country to the Virgin Mary described in it, in addition to the patronage of Mary in the Hungarian bishoprics of the time.

[1] Herwig Wolfram, Conrad II 990-1039. Emperor of Three Kingdoms, University Park, 2006, pp. 227–238.

[2] R. L. Benson (ed.), Imperial Lives and Letters in the Eleventh Century, transl. Th. E. Mommsen and K. F. Morrison, New York, 1962, p. 85.

[3] Gábor Klaniczay et al. (eds.), The Sanctity of the Leaders. Holy Kings, Princes, Bishops and Abbots from Central Europe (11th to 13th Centuries), transl. Cristian Gaşpar, Budapest–New York, 2023, pp. 71–72.

[4] The Sanctity of the Leaders, p. 73.

[5] Imperial Lives and Letters, p. 85.

[6] Mayke de Jong, ‘Carolingian monasticism: the power of prayer’, in Rosamond McKitterick (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 2, Cambridge, 1995, p. 651.

Related articles: