Reading Bishop Suriel’s Habib Girgis and the Education of a Coptic nation

‘The church of today rests upon three very important pillars. The first is the Blood of the Martyrs. The second is Monasticism. And the third is the School of Alexandria.’ - Abouna Youssef Khalil

There was a time not too far off in the recent past when very few people in the Western world would have recognized words like ‘Copt’ or ‘Coptic Christian.’ In 2015, ISIS extremists abducted and murdered 21 Coptic migrant workers in Libya who elected to be killed rather than convert to Islam and be released. As a result, the popular awareness of Copts in the Western consciousness has become more consolidated, and their identity more widely recognized.

The 21 Martyrs of Libya, as they are called in the church, are a new and important addition to the long list of cultural, religious, and historically significant figures that make up the tapestry of Coptic identity today. But there is more to Egypt’s Copts than the 21 Martyrs alone, or martyrdom itself, both past and present. When Abouna Youssef Khalil, Archpriest of St Mary and Archangel Michael church in Budapest, was interviewed by the Danube Institute in July of this year, he stressed that the Coptic church was founded on not one, but three pillars—Martyrdom, Monasticism, and the School of Alexandria. In this three-part series, I will introduce the Copts of Egypt in relation to each of these three pillars, and explain how they have shaped the Coptic people and faith, pash and present.

The School of Alexandria, From Birth to Resurrection

Coptic Christianity is said to have begun when St Mark the Evangelist, author of the eponymous Gospel, arrived in Egypt sometime around 42 AD. St Mark remained there for seven years, and founded a church which still stands as the historical seat of the Pope of Alexandria (one of five cities whose religious leaders were afforded that title under the Pentarchy system, along with Antioch, Constantinople, Jerusalem, and Rome). The School of Alexandria, which blossomed from the seeds sown by St Mark, developed over time, and came to have two very distinct meanings: one conceptual, one literal. Both meanings are simultaneously and intrinsically linked to Egypt’s Copts, and to what they believe today.

Conceptually, the School of Alexandria is an intellectual school of thought and the culture associated with it, both of which developed over several centuries in Egypt during the pivotal years of early Christianity. Many scholars and saints belong to this school—St Origen, St Clement, St Athanasius, and St Dioscorus the Great (known to Copts as the Champion of Orthodoxy for his stance at the Council of Chalcedon in 451). The writings, teachings, and works of these church fathers shaped and continue to shape apostolic Christianity and are relevant not only to Coptic Christians but to Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and other Oriental Orthodox believers even today.

Literally, the School of Alexandria was also a place—a physical school with its own dean and hierarchical structure.

This was where the church fathers would teach and lecture to students who brought Christian theology and praxis not only to other parts of Egypt, but to the entire ancient world. Scholars from across the Roman Empire would also come to the school to learn, making Alexandria one of the most important nodes in the network of early Christianity for its time. In the words of Dom. D. Rees:

‘The most renowned intellectual institution in the early Christian world was undoubtedly the Catechetical School (Didascaleion) of Alexandria, and its primary concern was the study of the Bible, giving its name to an influential tradition of scriptural interpretation. The preoccupation of this school of exegesis was to discover everywhere the spiritual sense underlying the written word of the Scripture.’

Unlike its intellectual counterpart, the physical School of Alexandria lost its status around the time of the Council of Chalcedon and fell into obscurity after the Islamic invasions placed Egypt firmly under Muslim rule. The centuries that followed saw a gradual but decisive process of disenfranchisement as Copts were converted (sometimes by force) to Islam, and Coptic institutions—including schools, churches, monasteries, and libraries—were appropriated by or repurposed for the benefit of Islam and its followers.

According to economic historian Mohamed Saleh, a decisive factor in this conversion was the presence of the Islamic poll tax, or the jizya: the annual tax paid by non-Muslims in exchange for the guarantee of safety when living under the governance of Islamic rule. Saleh shows that between 641 and 1856, when the jizya was in effect, a gradual and pronounced process of religious shift can be identified—something that was most prominent among the lower socioeconomic classes of Coptic Egyptian society. Those who could afford to retain their religion largely did so; those who could not, did not.

By the early modern period, after twelve centuries of Islamic rule, Egypt’s Copts were left in a peculiarly difficult situation. Socioeconomically, they were successful, but culturally and religiously, they were in dire straits. More than anything,

Copts had become entirely deprived of the socioreligious infrastructure bequeathed to them by the School of Alexandria

in the early centuries of Christianity; the churches, cathedrals, libraries, and monasteries that were built for them had long since been converted into mosques or expropriated for some other use. In some cases, they were simply demolished. The patriarchal libraries that once served as the beating heart of Christian scholastic life in Egypt became closed off to outsiders, and knowledge of the faith became less and less accessible even to the faithful.

Even in these dire straits, the spirit of the School of Alexandria survived—and indeed thrived—in large part due to the widespread use of an educational system imported by the Arabs known in Arabic as ‘Kuttab.’ The Kuttab system, meaning ‘according to the book,’ was used by both Christians and Muslims in Egypt, and entailed rote memorization as well as extensive lecture-based instruction on geometry, arithmetic, religion, and good manners. Both Christians and Muslims learned scriptural exegesis (called tafsir in Islam) from local teachers who were supported by their communities—either wealthy families or local bishops and church leaders. Coptic Christians were deprived, to be sure; but they, like the School of Alexandria, survived. Yet in the 1800s Copts would be confronted by a threat that had nothing to do with Islam or Muslims, but everything to do with the West and its Enlightenment values.

In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt, seeking to stymie Britain’s ability to trade with its cash-cow colony of India. Bringing the full might of Revolutionary France upon an unprepared and underdeveloped Ottoman backwater, Napoleon first made landfall at Alexandria before storming up the Nile and taking Cairo in Blitzkrieg-like fashion, winning battle after battle in a campaign that left Egyptian defenders (Christian and Muslim alike) dazed and disillusioned. Ultimately, the French occupation would last only a scant three years before being ousted from Egypt in 1801, but their conquests and archaeological accomplishments (such as the discovery of the Rosetta Stone) constituted an attractive legacy that left the Western gaze fixed upon Egypt.

The Enlightenment values of secularism and rationalism (a word we should take with a grain of salt) brought by these newcomers led to what Bishop Suriel refers to as a profound ‘dislocation of values.’ But that was not all. As Britain and France competed for Egypt, foreign missionaries, educators, and financial speculators flooded into the country, seeking to win influence for their nations and to locate opportunities in formerly Ottoman-ruled lands. Both before and after the British takeover in 1882, Protestant and Catholic missionaries also competed for converts—not among Egyptian’s majority Muslim population, but instead among the Copts, who were seen at this time as misguided and archaic demi-Christians that needed to be brought back into the fold.

As the influence of the Coptic church continued to dwindle under the administration of the British, who were more interested in excavating Ancient Egyptian relics and soothing local Muslim leaders than they were entreating with the church of St Mark, a serious capability gap between Western and Eastern Christian institutions became apparent. Whether Protestant, Catholic, or something else, Western missionaries in Egypt had the advantage of being able to deploy highly sophisticated frameworks and principles; these included Sunday Schools for children (pioneered in England in the 18th century), church-led activity groups for men and women, Christian charity organizations providing welfare for the homeless and the sick, and much, much more.

The gulf between the missionaries, who practiced a bold, open, and confident version of Christianity, and the Copts, who after centuries of Muslim rule had come to practice a timid, closed, and secretive Christianity, was profound. Exploiting this gap, and benefiting from their advanced methods of organizing, preaching, and convincing the unconverted, the Western arrivals took to their mission, which Bishop Suriel describes in the following manner:

‘The missionaries’ ultimate goal was to colonize the Egyptian mind. The missionaries believed that in order for the Copts to convert to an “unadulterated” Christianity, they had to conform to an evangelical mindset rooted in a particular interpretation of the Scriptures.’

The main vehicle for the colonization that Bishop Suriel describes was education.

Education, by itself, is not and has never been perceived negatively by Egypt’s Copts. Yet the various Christian seminaries and schools established by British and French expatriates in Egypt weaponized education as a means by which to undermine the confidence among Egyptian Copts in their identity, heritage, and religious convictions—supplanting these with Western visions about how Christianity should be practiced, and what Christians should believe.

During the papacy of Pope Kyrillos V, the Coptic Church came to realize that it had to fight fire with fire. In the face of the challenges imposed upon the church by opposing forces, Pope Kyrillos elected to reform church practices (but not doctrine) by learning from the Western missionaries and their emphatic focus on education as a tool for instructing future Christian minds. To that end, in 1893 he inaugurated the Coptic Theological Seminary, established as a direct successor and continuation of the School of Alexandria. At this school, Coptic Christian students were instructed in Coptic theology, the Coptic language, and other subjects, utilizing the Western style of education adopted from British and French missionaries working in Egypt. Furthermore, the entire content of the Coptic Patriarchal Library in Cairo was made accessible to all students of the seminary—marking the first time in modern history where Coptic theological wisdom was offered to those not inducted into the priestly or monastic lifestyles.

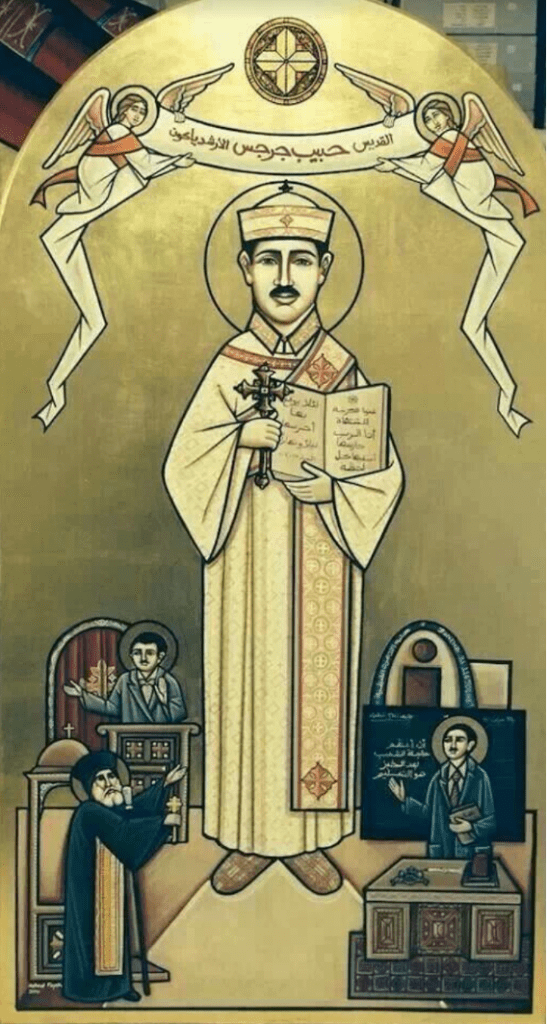

The resurrecting of the School of Alexandria by Pope Kyrillos V as the Coptic Theological Seminary paved the way for the ‘Coptic revival’ of the 20th century. An early graduate of the school was Habib Girgis, who established Sunday schools to teach young children Coptic doctrine. Having realized how the organizational structures and frameworks exported to Egypt by Western missionaries might benefit Copts if appropriately reconfigured, Girgis dedicated his life to the establishment of Sunday schools throughout Egypt—particularly in rural and impoverished areas where Christian Egyptians had for centuries been deprived of access to any kind of formal instruction in the religion they were born into. The educational format Girgis established is now a standard part of life and schooling for Coptic Christians, both in Egypt as well as among diaspora populations in Australia, the United States, Hungary, and many more countries worldwide. By doing so, Girgis was not merely copying Western systems of education to suit his own needs—rather,

he combined Western ingenuity with the wisdom of the School of Alexandria,

and thereby innovated a model of religious education that is now enjoyed by Copts around the world.

In conclusion, when asking who exactly Egypt’s Copts are, and what they believe, we invariably find that the three pillars of faith for Coptic Christians — Martyrdom, Monasticism, and the School of Alexandria—will be found somewhere within the answers given. For Coptic Christians, the School of Alexandria itself is not merely a literal place, or indeed a theological concept; rather it is both things, as well as a deeply treasured religious tradition integral to Coptic identity and thought today as in the past.