‘The church of today rests upon three very important pillars. The first is the Blood of the Martyrs. The second is Monasticism. And the third is the School of Alexandria.’

– Abouna Youssef Khalil

In the first entry of our three-part series on Egypt’s Copts and the pillars of Coptic Christianity, we discussed the School of Alexandria. Thought to have been founded by the Apostle Mark the Evangelist around 42 AD, the school played a major role in the critical stages of early Christianity, nurturing talented scholar-saints such as Origen, Clement, Athanasius, and perhaps more controversially to non-Coptic audiences, St Discorus (who was an active participant in the events that led to the schism between Oriental Orthodoxy and Roman Christianity in 451). In the second part of our series, we will examine another pillar of the Coptic Church that arguably played an even greater role in the history of Christianity as a whole. It originated an ascetic lifestyle, an occupation, and a way of thinking about faith and the world that even today retains a presence across almost the entire globe. I am speaking, of course, about monasticism—a cornerstone of Christianity that few now even recognize as an authentically Egyptian innovation.

In 2017, conservative thinker Rod Dreher published The Benedict Option, a religiously inspired meditation on the contemporary phenomenon of sociocultural decay in the Western world. At its core, the book is a manifesto; it is deliberately designed to be a call to action for those unnerved or alarmed by the decline, who wish to ensure the safety and innocence of their families and close friends in defiance of these prevailing trends. Numerous strategies are proposed, critiqued, and considered as potential means by which to successfully survive this cultural apocalypse (a term that is only a slight exaggeration) that Dreher argues we are presently experiencing. The person at the heart of all Dreher’s arguments, though, is an Italian (or late Roman) monk known as St Benedict; a man who lived between the 5th and 6th centuries AD, whose experience of the increasingly corrupt and chaotic society of his time gave rise to feelings of disillusion and Durkheimian anomie so profound and severe that he was forced into radical action.

The radical action taken by St Benedict, who was undeniably a religious extremist in comparison with the norms and values of contemporary society, is very far from what a modern observer might predict—especially in the context of the countless violent acts committed by religious fanatics across the world in modern times. Unlike the so-called ‘religious’ extremists, St Benedict’s response did not involve strapping a bomb to his back or attacking random civilians with knives and guns. Rather, he opted to withdraw from the sickness in society he knew he alone could not cure, and instead embarked upon a way of life that has no instruction manual, no textbook, and no teachers to instruct or guide him along the way. The way of life in question, of course, was monasticism, and in the monastic life St Benedict did indeed earn the veneration he still commands today. While I recommend that those interested in the fruits of St Benedict’s labour consult Dreher’s book in full, the fact that the monastic community St Benedict founded almost 1500 years ago still exists today in the heart of Italy speaks for itself as a testament to the success of his endeavours.

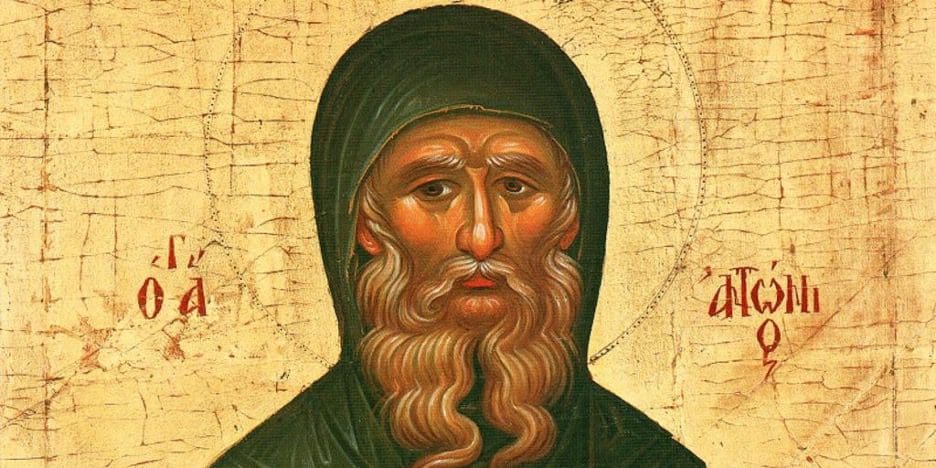

But while St Benedict of Nursia may not have had an instruction manual, textbook, or teacher, he did indeed have a role model. This person earns only one mention across the entirety of Dreher’s work, appearing just once on page 14, but as the founder of Christian monasticism he would presumably not take offense to that fact. The role model in question is none other than St Antonious the Great, or St Anthony, to most Western Christians, and it is to him that the nearly 2000 years of Christian monasticism can be accredited.

Very little is known about the life of St Anthony prior to his embarking upon the hermetic life of a Christian monk that at the time was entirely undefined. What we do know comes almost solely from St Athanasius, a Doctor of the Church who played a critically important role in the School of Alexandria and in Nicene Christian theology.

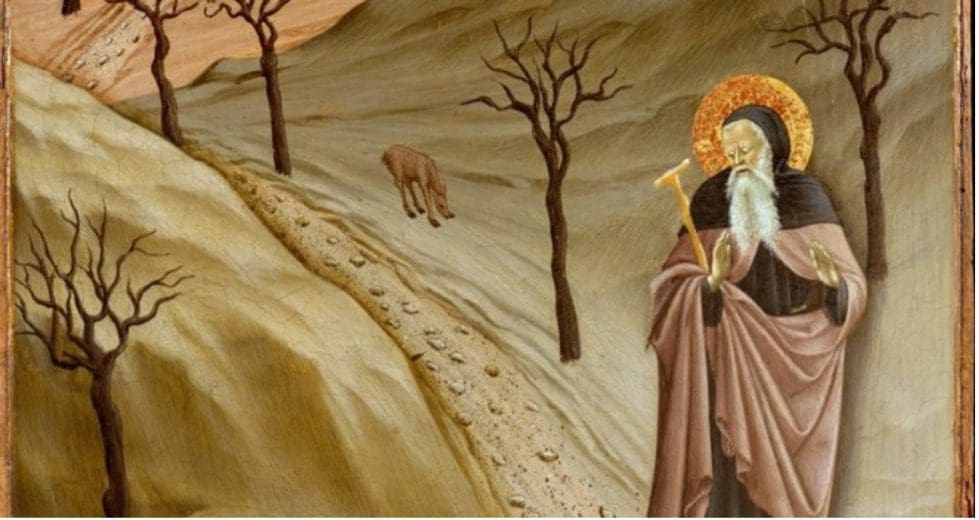

Athanasius tells us that St Anthony was born into an affluent family of landowners in upper (northern) Egypt, who gave him a Christian upbringing that was typical for the time, albeit with less emphasis upon Biblical studies given his lack of interest in and patience for the written word. In his late teens or early 20s, Anthony’s parents died, leaving him as the sole inheritor of their wealth. This loss was evidently painful for the soon-to-be monk, and in the aftermath he is described as attending church multiple times a day, for multiple months at a time, which only ended when the young Anthony became struck by a revelation instructing him to follow the words given in Matthew 19:21: to sell his possessions, to give all he owned to the poor, and to ‘follow’ Christ, which for reasons known only to Anthony himself, led him into the hostile Egyptian desert.

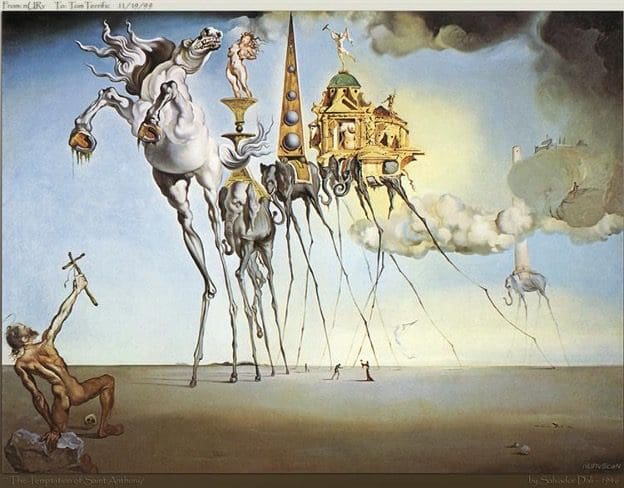

What followed from the Egyptian saint’s self-imposed exile is effectively unverifiable, although numerous writings attesting to acts or even miracles performed by the desert hermit have been recovered. One of the most famous episodes of the genre is the spiritual war allegedly waged between St Anthony during his desert isolation, and Satan, fulfilling his role as the ‘great tempter’ working to thwart such spiritual pursuits. As St Athanasius describes it: ‘When we visited St Anthony in the ruins where he lived, we heard a commotion, thousands of voices and the clash of arms. Also, at night, wild beasts would come, and the saint fought them off with prayer.’ This episode in the life of St Anthony was and still is so dramatic that it has earned itself a perennial place in Western art and culture, being depicted in paintings by Hieronymus Bosch, Matthias Grunewald, Paul Cezanne, and Salvador Dali among many more.

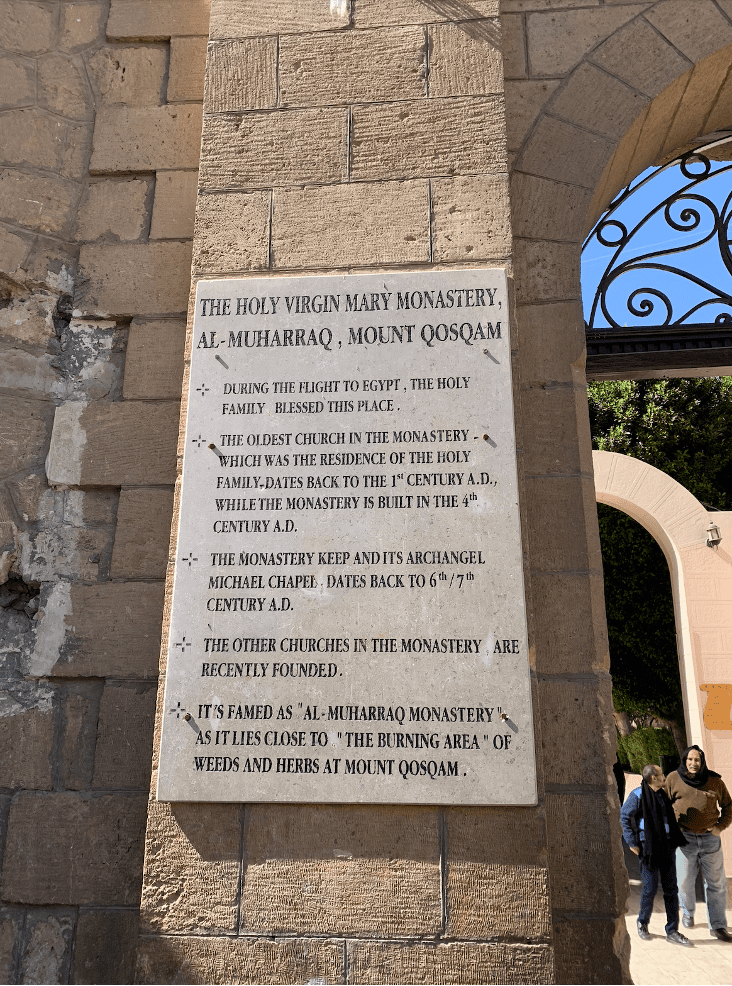

Over time, St Anthony attracted a cadre of disciples, whom he organized into what would later become the hierarchical structure of a modern monastery. The legacy of these efforts still exists today in monasteries such as the Holy Virgin Mary Monastery in Egypt, known also by its Arabic name ‘Deir el-Muharraq’, where the pillar of monasticism still survives and thrives in the modern age, and continues to influence the thought and feelings of Coptic Christians even now.

For those of us living in the present day who seek to understand Coptic Christianity, from its very beginnings roughly 2000 years ago to the present day, it is a simple fact that not all questions are born equal. For scholars of Egypt’s Copts and their beliefs, it is ultimately not worth asking whether Saint Anthony truly deserves to be called the ‘father of monasticism’ (a title that has been contested by some Western scholars in recent years). To interrogate the historical accuracy of the acts he is remembered for is also ultimately missing the point. What matters is that St. Anthony and the role he played in collecting Egyptian Christian disciples around him to form a new kind of institution are real—if not according to objective historical records, then at the very least in the minds and beliefs of millions of Coptic Christians not only in Egypt, but around the entire world. Pre-empting such concerns, St. Athanasius assures us not to worry about the details of St. Anthony’s life, as ‘when all have told their tale, the account will hardly be in proportion to his merits.’