‘The church of today rests upon three very important pillars. The first is the Blood of the Martyrs. The second is Monasticism. And the third is the School of Alexandria.’

– Abouna Youssef Khalil

In the first entry of our three-part series on Egypt’s Copts and the pillars of Coptic Christianity, we discussed the School of Alexandria. In Part 2, we focused on the ascetic tradition of monasticism, which began in the Egyptian desert with St Antonius the Great, but has since become a cornerstone of Christianity as we know it. As we reach the finale of this series, which deals with the third and final pillar of Coptic Christianity—martyrdom—it is worthwhile to remember what led us here to begin with.

Who exactly are the Copts? And what does it mean to be a Coptic Christian? In Hungary, as in the rest of the Western World, these questions were not commonly asked, nor were they considered particularly relevant or topical, throughout modern times. Today, that is no longer the case. For the first time in recent memory, Westerners have become familiar with the word ‘Copt’, and become aware of the fact that in Egypt—the beating heart of the Middle East, home to great pyramids and obelisks, sand-blasted cities lost to time, and to countless mosques from which the call to prayer can be heard on loudspeakers five times a day—there are in fact Christians as well. This newfound awareness was not an accident, nor did it result from some collective spontaneous interest in Copts or their ancient faith. Rather, it emerged as the consequence of a specific event—an event which both inspired and horrified, in equal measure.

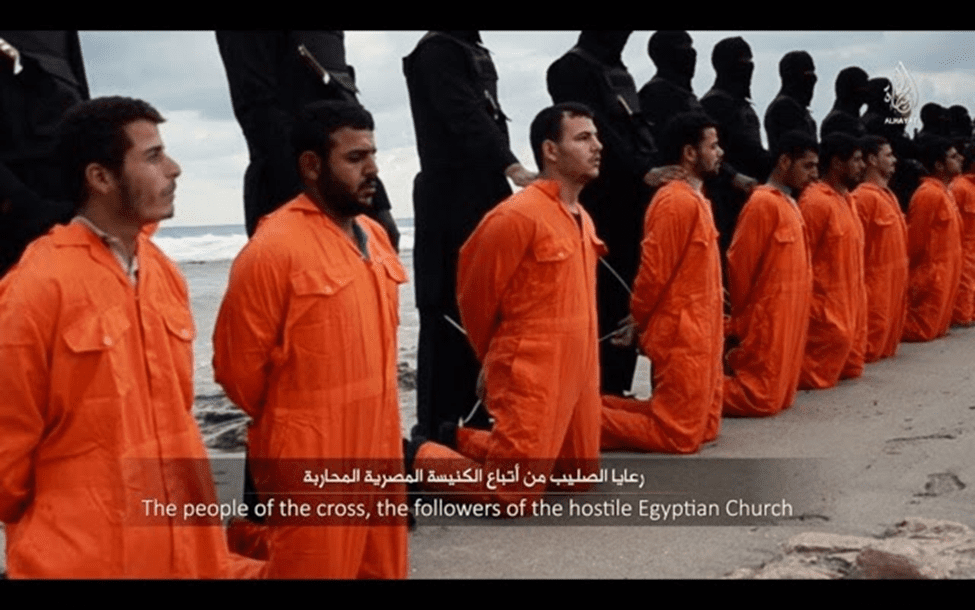

On 12 February 2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria made an announcement that shocked the entire world. Through the seventh edition of their web-only propaganda magazine Dabiq, the Islamic State proudly reported that they had kidnapped and intended to kill 21 Coptic migrant workers in Libya, ostensibly as a retaliatory act against the actions of Western ‘crusaders’ in Syria and Iraq. The prisoners had reportedly been offered freedom upon converting to Islam, but had refused to do so. The report was horrifying enough, and the accompanying photographs (slickly compiled by Islamic State’s al-Hayat Media Center) were frightening enough to curdle one’s blood. If, like me, you had read the report detailing these shameless threats on 12 February, you would have found it impossible to imagine, let alone comprehend. And so I lived in disbelief for the following three days, until al-Hayat Media Center released a video footage of the atrocity to emphasise their unrelenting glee over what they had done.

The five-minute video begins with introductory speeches in impeccable American-accented English, glorifying the Islamic State and describing what is about to ensue as ‘Muhammad’s answer’ to the ‘nation of the cross.’ Subsequently, the kidnapped Copts – wearing bright orange jumpsuits, coordinated as if for a perverse publicity photoshoot—are shown kneeling on the sands of a Libyan beach, where they are summarily decapitated. More speeches are made, the video concludes, and the horror of what we have witnessed sinks down like a stone.

As news of this evil atrocity spread like wildfire across the world, it was described by the media in many ways: as a massacre, a mass murder, an act of genocide. To Coptic Christians, what took place on 15 February was all of these things, but far more importantly, it was an act of martyrdom. The emphasis, for Copts, is not on the actions of the perpetrators, but on the actions of the victims. What is emphasised is a collective decision made by 21 souls—a conscious choice—to refuse apostasy in the face of death, which would ultimately lead them to a Libyan beach upon whose sands their blood would be spilled.

Unfortunately, as the 21 came to dominate the news cycle during the first six months of 2015, something very regretful happened. While Copts suddenly shot up to the forefront of public awareness for Western observers (much like what happened with Yazidi Kurds in 2014), this awareness revolved around the revolting nature of the crime committed, and the perpetrators who committed it, rather than those it was committed to. The conceptualisation of Copts became dominated by images of black-clad men killing anonymous victims in orange jumpsuits; images that induce retroactive and reflexive feelings of anger and sympathy, but not admiration or understanding.

The intentionality and agency of the victims, or rather the martyrs, of Libya is the focus of a 2019 book called The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic Martyrs by German Catholic writer Martin Mosebach. As a writer and activist, Mosebach played a significant role in sharing the events that took place in Libya to an international audience, both in the West and beyond. Mosebach’s book names each and every one of the martyrs, describing them not as passive victims but as active heroes in a tragic drama— a characterisation that aligns more closely with how the martyrs are viewed by Copts themselves.

The sanctification and heroic embellishment of martyrs, and of martyrdom as a deliberate act of the free human spirit, was at one point in time an important feature of all Christian denominations. Although there are considerable differences between these denominations in how they approach the aesthetic of martyrdom today, they nevertheless share a common descent that leads back to early Christianity—a period in which mass executions and killings of Christian believers were a very widespread phenomenon both within and outside of the Roman Empire. During this time, Christians suffering from persecution drew inspiration from the definitive character in their religion, Jesus Christ, and theodicised a response to their aggressors by willingly accepting death with their heads held high. This concept of ‘stoic, pious acceptance as heroism’ is a distinguishing feature that separates the martyrdom of early Christianity from its antecedents in the Old Testament and Judaism, such as the Judge Samson and King Saul, and when demonstrated during public persecutions or mass killings, it became a powerful attestation of religious conviction that was profoundly influential to the bystanders or observing civilians in the Roman Empire. People who witnessed the persecutions, or heard news of them, were forced to make sense of the supremely unblemished confidence of these protomartyrs, who did not offer resistance to their persecutors because they considered their own deaths in the faith as a kind of victory.

The stoic acceptance of suffering is a virtue highlighted by all Christians, but it is the extreme case of martyrdom where the Coptic Church is arguably distinct from the rest. While it is not the only denomination to feature extensive martyrologies during mass (the Synaxarion), the religious calendar used by the church does not date back to the birth of Christ as other denominations do, but rather to the year 284 A.D.; the year when Emperor Diocletian came to power in the empire, initiating a regime of violent persecutions that were the worst in Christian history until that time. Copts are thus living literally in Anno Martyrum (the year of the martyrs) rather than in Anno Domini (the year of our lord). These features of the church, among many others which may be both religious and cultural, bestow individual Copts with a direct and personal engagement to the concept of martyrdom as a supremely sacred act; a kind of higher calling which should under no circumstances be sought out, but could at any time fall upon an individual believer, in which case it can either be refused, or accepted with a clear conscience and a steady mind. The 21 Martyrs of Libya, who were tortured by ISIS for months after being kidnapped as a way to coerce a religious conversion but did not yield, were able to accept their fate so readily because when the time came they had a familiarity and a lucid understanding of their situation and what it meant. To them, this was something they had seen before; something they had read about and heard about for their entire lives, enabling them to behave with a calmness in the final moments of their lives that has been seen as shocking, disturbing, or even unnatural to Western observers, to whom this intense relationship with martyrdom is entirely unfamiliar by comparison.

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the 21 Martyrs though is the fact that one among their number was not a Coptic Christian at all. Though now canonized by the church as St Matthew the Copt, the man—Matthew Ayariga—was a West African immigrant who had come to Libya in order to cross the Mediterranean into Europe. According to Mosebach’s research, his kidnappers did not consider him to be a Christian at all, and were intending to let him go.[1] Yet St Matthew chose voluntarily to go with his companions and die as one of them. While we will never know what thoughts occupied the minds of St Matthew and his companions in those final moments, or in the brutal months preceding them, their actions are seen by Copts today as a source of pride. The 21 Martyrs of Libya are viewed by Copts as a validation of their faith and community as believers, and as unshakeable proof that their church today continues to face evil and persecution with the same grace and pride that it did nearly 2000 years ago.

In memoriam:

Tawadros Youssef Tawadros

Magued Seliman Shehata

Hany Abd el Messiah

Ezzat Boushra Youssef

Malak (the elder) Farag Ibrahim

Samuel (the elder) Alham Wilson

Malak (the younger) Ibrahim Seniut

Luka Nagati Anis

Sameh Salah Farouk

Milad Makin Zaky

Issam Baddar Samir

Youssef Shoukry Younan

Bishoy Stefanos Kamel

Abanub Ayat Shahata

Girgis (the elder) Samir Megally

Mina Fayez Aziz

Kiryollos Boushra Fawzy

Gaber Mounir Adly

Samuel (the younger) Stefanos Kamel

Girgis (the younger) Milad Seniut

Matthew Ayariga

[1] Martin Mosebach, The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic Martyrs, Plough Publishing House, 2019, 112.