Hungarian Conservative has launched a ten-part series of articles on the past decade and a half of the Hungarian economy and society, titled ‘Revealing the Facts’. Rather than looking at a lot of different, isolated data, it is worth providing an overview, comparing, and analysing trends over time, in order to understand the details. As we detailed in the previous parts, stable work and growing incomes), that is, the security of livelihood, are economically the most important for the Hungarian people. The improvement of living conditions, the reduction of poverty and the increase in family benefits has been the great achievements of recent years. Now inflation has not hit the Hungarian people as hard as it did during the regime change. Both the population and the economic players have been able to move forward, we have achieved substantial economic growth, which has been accompanied by a decade-long improvement in fertility. In the eighth instalment our authors highlighted the turnaround in Hungary’s tax system after 2010, while in the previous piece they focused on the history of innovation in Hungary. To conclude the series, we present the labour market situation of women from a different perspective than the usual feminist one.

‘Thank you, women who work! You are present and active in every area of life – social, economic, cultural, artistic and political. In this way you make an indispensable contribution to the growth of a culture which unites reason and feeling, to a model of life ever open to the sense of “mystery”, to the establishment of economic and political structures ever more worthy of humanity.’ (Pope John Paul II)

Today, unfortunately, women can only be discussed from the perspective of left-wing gender ideologists, i.e. only the differences between men and women are allowed to be examined. According to them, women are disadvantaged if they differ from men in any way, and their only legitimate aim is to eliminate this difference.

If someone dares to compare the situation of Hungarian women not to that of Hungarian men, but to that of women in another country, his or her analysis will not be considered gender-sensitive and thus, it will be stigmatized. But in reality, no meaningful action can be taken if our thinking is unnecessarily shackled.

Employment

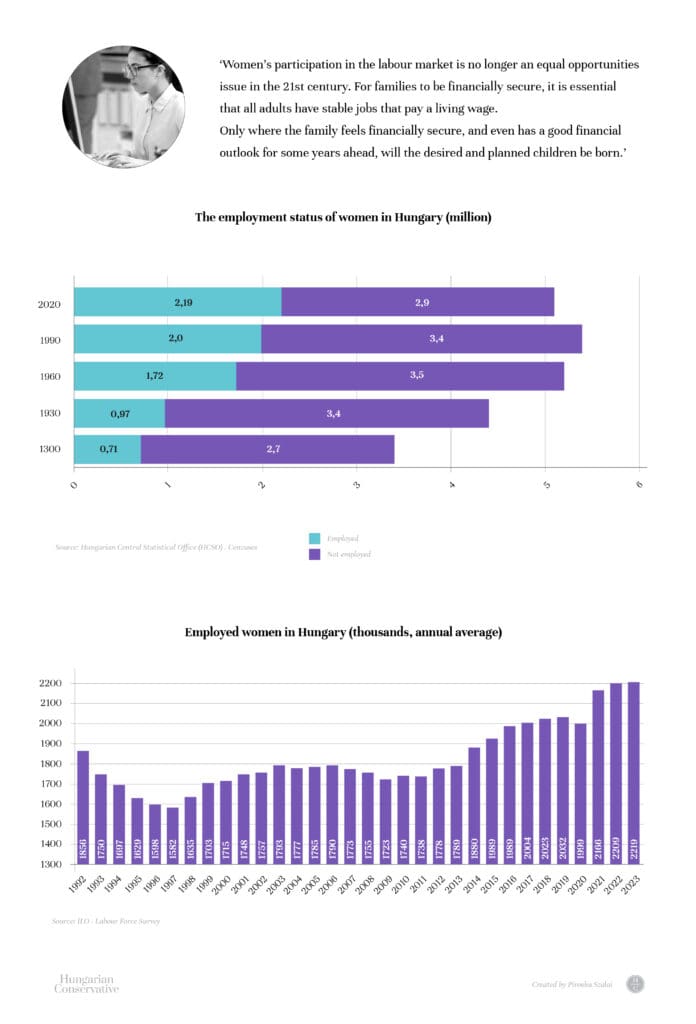

Women’s participation in the labour market is no longer an equal opportunities issue in the 21st century. For families to be financially secure, it is essential that all adults have stable jobs that pay a living wage. Only where the family feels financially secure, and even has a good financial outlook for some years ahead, will the desired and planned children be born. If parents believe that having a child will mean an unbearable additional risk of poverty, they will postpone having a child.

The high participation of women in the labour market in the Eastern bloc after WWII is not the result of feminist struggles. In these countries, women everywhere started working full-time as early as the 1950s, whereas in the Western world it was not until the 1970s, and the process was much slower, with many countries moving to part-time work first.

More than two million women worked in Hungary before the change of regime. Their number reached its lowest point in 1997, falling by almost half a million to 1 million 582 thousand. The last time the number of working women was so low was in the 1950s, after the Second World War. After decades of bleak labour market conditions, the average number of women in employment reached 2 million again in 2017.

In contrast to previous crises, employment in Hungary did not decline during the polycrisis period after 2020. There was a dip in the second quarter of 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, which reduced average annual employment by 33,000, but within a year we not only corrected this but also managed to increase it significantly.

Women have accounted for the largest share of labour market growth in Hungary in recent years.

The growth was mainly driven by women aged over 55 and those with young children. Since 2014, mothers have been able to work legally from the age of six months of their child without having to give up the childcare fee (GYED), thanks to a measure called GYED extra. The impact of this measure is clearly visible in the graph above, as a significant improvement in women’s employment started in 2014. The increase in the number of women aged 55 and over in the labour market is partly due to the extension of the retirement age and partly to the fact that a much higher proportion of women aged 55–64 now have secondary and tertiary education than in 2010, when the age group was made up of those born at the end of the war. Those with at least secondary education are better able to maintain their employability until retirement age.

In their writings, feminists repeatedly highlight the under-representation of women in managerial positions. On average, women hold one third of managerial positions in the EU. In Hungary, the figure has been 39–40 per cent since 2010, and although it dropped a little during the COVID-19 pandemic, we are still among the top member states. ILO, the UN’s labour organization, also has a rate for senior and middle management positions in its databases, which is also above 35 per cent in Hungary.

As we analysed previously, Hungary has a particularly high share of people working in high-tech sectors in the labour market. This is also the case for women, with 5.1 per cent of female employees working in high-tech sectors in 2022, the fourth highest share in the EU after Ireland, Estonia and Slovenia. Of these, 2.7 per cent work in high-tech manufacturing, by far the highest share after Ireland.

Earnings

In fact, until the fifties, women’s income was more of a supplement to the family budget. Until the middle of the 20th century, our great-grandmothers’ income came from milk, eggs and garden produce. From the 1950s, however, the two-earner family model became commonplace, with women’s income becoming one of the pillars of the family’s livelihood. Without either the woman’s or the man’s wages, the family’s financial base would be eroded.

Another problem that is misidentified in ideologically driven analyses is the gender pay gap. Many consider this to be the most important indicator of women’s economic status. The pay gap never compares the earnings of women and men with the same seniority in the same job. Nor are these indicators suitable for analysing the financial situation, as they only take into account the gross earnings of workers, not the number of family members, nor any tax or other benefits or social security allowances. Furthermore, they do not cover all workers, as they do not consider workers in micro-enterprises or in certain sectors.

Moreover, each of the major organizations uses different indicators. The OECD looks at the median of total earnings, which they say is average for Hungary, while Eurostat looks at the difference in average gross hourly earnings by gender, where they say we are much worse than the EU average.

Risk of Poverty

We believe that a much more accurate picture of the economic situation of women is provided by looking at the proportion of women at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The latest figures from Eurostat are for the reference year 2021. At that time, the proportion of women at risk in Hungary was 1.7 percentage points higher than for men, a much smaller gap than the EU average of 2.3 percentage points.

***

With this series, we wanted to provide a factual snapshot of the progress Hungary has made over the past decade and a half. There have been peaceful years during this period, but since 2020, one unexpected challenge after another has kicked down the door. Even in these years of polycrisis, we have coped better than we did in the years of the financial crisis between 2006 and 2010. This has required good governance, fast and effective action and the cooperation of all actors involved.

Piroska Szalai is a labour market expert, a researcher at Economy and Competitiveness Research Institute of the Ludovika University of Public Service.

Mátyás Zsolt Varga is a journalist at Mandiner.