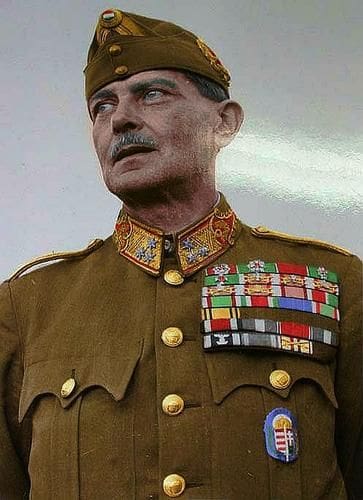

Gusztáv Jány (born Hautzinger) was the commander of the Hungarian Second Army, which saw its demise on the Eastern Front near the Don River, at the time of the Battle of Stalingrad. His tragic fate and bravery mirror those of his army, and, in many ways, of Hungary itself.

Early Life

Gusztáv Jány was born in 1883, to a Hungarian German family. After being educated in two Lutheran high schools, he enrolled in the Ludovica Academy, the military school of Austro–Hungary. Jány graduated in 1905, becoming a lieutenant, and subsequently started to serve in an infantry battalion of the Austro–Hungarian Empire. Later, he continued his studies in Budapest, and, as one of the best students, he was sent to the Vienna military academy as well, where he graduated as a first lieutenant.

When the First World War broke out, Jány was sent to the front as an infantry officer. He saw action first against the Russians in the Eastern part of Austro–Hungary, around Galicia, fighting so gallantly that he was promoted to captain as soon as 1914. During the course of the war, Jány mostly fought on the Galician Front, however, in 1917, he was sent to the Western Front to study the tactics of the German army. During 1918–19, Jány served in ministerial and other government positions, until

he was appointed commander of the legendary Székely Battalion,

consisting of Transylvanian Szekler Hungarians. However, since the Hungarian Soviet Republic disbanded the battalion, Jány decided to surrender to the Romanians. He was arrested and held on unclear charges, until his release in 1920.

Interwar Years

Upon his return to Hungary, Jány reported for duty. He was promoted to major and was entrusted with the command of an infantry battalion. However, since the Treaty of Trianon restricted the size of the Hungarian army, his unit was eventually disbanded, and Jány was was offered a university lecturer post at Ludovica. In 1924, he was knighted as member of the Order of Vitéz founded by Regent Miklós Horthy, and was promoted to the rank of colonel, but in order to qualify for the honour, he had to change his surname to his mother’s maiden name, Jány. During these years, Jány continued his activity as teacher, but also briefly headed a battalion, this time in Székesfehérvár.

In 1931, Jány was named as head of the Ludovica Academy. As a practising Lutheran, he ordered the construction of a Protestant oratory, and also considered it important to teach the cadets about the tragedy of the Trianon Treaty and the loss of Hungarian territories. In 1934, he was promoted to general, and, in 1936, Jány left the academy. He led various units until 1940, when he was named as commander of the Hungarian Second Army, a decisive and fateful post both in terms of Hungary’s future and his own life.

During the Second World War

Hungary entered the Second World War in 1941, declaring war on the Soviet Union, and Horthy, albeit unwillingly, sent the Second Army to the Eastern Front. The Hungarian troops were stationed around the Don River, near Stalingrad. Jány, by now Army General, found himself leading an offensive against the Soviets. It must be noted that Horthy believed that the offensive would be a short and victorious one, and the position he gave Jány was supposed to be a reward for his long and loyal service.

As commander, Jány often boosted the moral of his soldiers by visiting them on the front lines, often with his own small military airplane, named Gólya (‘Stork’). During one of these trips, he was wounded and had to be hospitalized.

Despite Jány’s eagerness to support his soldiers personally, the moral of the army swiftly deteriorated due to the freezing of the front lines during the summer of 1942. Reinforcements and supplies were not arriving, and the soldiers ran out of ammunition. Atop of all this,

the Germans assigned unrealistic tasks to the Hungarians.

Therefore, Jány requested his relief from his post during the autumn, which Horthy declined, and instead ordered him to keep the lines at all cost. The Germans did little to help the increasingly desperate Second Army, while pressured the Hungarian military leadership to hold the lines regardless of the lack of appropriate clothing, ammunition and food supplies of the Hungarian troops. Meanwhile, the Germans were suffering heavy losses themselves and were forced to retreat inside the city of Stalingrad.

In January 1943, the Hungarian Second Army started to disintegrate and could no longer hold up the advancing Soviets. Enraged by their failure, Jány issued his infamous order, in which he declared that the Second Army had ‘lost its honour’, and ordered continuous resistance, until the end. However, two days later, Jány realized that the situation was untenable, and ordered the soldiers to fall back, and, in March, he officially revoked his January order. During the spring of 1943, the Hungarian Second Army, or rather, what was left of it, was pulled back from the front and sent back to Hungary. Jány himself only left with the last transport in May. Upon his arrival, he was finally relieved from his post, almost a year after he had pleaded for this decision.

After the Tragedy and Conclusion

After his traumatic experience, Jány did not take active part in the course of the war anymore. Furthermore, he specifically refused to hold any post under the Nazi puppet government of Ferenc Szálasi, which took over in October 1944. During 1945, Jány fled to Germany, but

he declined the US offer to be airlifted to Spain.

Jány argued that he must tell the truth about the tragedy of the Second Army, and side with his comrades, who might be unfairly blamed for the catastrophe. He, furthermore, did not fear retribution, as he considered himself innocent. Despite of his clear conscience, he rightly suspected that the Communist-influenced court will seek to execute him. And even so, Jány voluntarily returned to Hungary in 1946. He was arrested and accused of war crimes. His case was handled by a special and political ‘people’s court’, and not by a regular, military court.

The Communists thus strongly influenced the work of the court, in an attempt to exploit Jány’s case for their political aims. It is telling that the court was forced to send back the court materials to the prosecutors, as those did not hold enough damning evidence of Jány.

Jány was finally sentenced to death for allegedly ordering the execution of abducted civilians, soldiers, and partisans. He was also found guilty of having advocated for the war. Of course, the entire proceedings was lawless. The first main count against Jány could not and was not verified, while the second count was even more absurd, since, as a soldier, Jány had no say in whether Hungary should or should not go to war against the Soviets. The only seriously morally dubious action Jány had taken was ordering the shooting of every tenth soldier of the troops that fled the Soviets. However, this order was largely symbolic, lightly executed, and later revoked by Jány himself. Despite the obvious lack of evidence to sustain the charges, Jány’s sentence was upheld. Famously, Jány refused to plead for clemency. He was executed by a firing squad in 1948 and buried in Budapest, in the Farkasrét Cemetery. His previous tombstone bore one of his last words:

‘I am not strong, but Christ behind me is.’

After the fall of Communism, historians started to debate the role of Jány. While some considered him reckless in ordering extended resistance, even after the Germans suffered heavy casualties, others argued that he merely used harsh methods to uphold discipline, which was crucial during the war situation. In legal terms, in 1993, Jány’s case was reviewed, and eventually, he was rehabilitated. His trial is now considered to have been one of the most blatantly unjust ones held between 1945 and 1950.

While Gusztáv Jány made several mistakes as commander of the Second Army, he behaved bravely during and after the war, especially during this trial. He was condemned in a kangaroo court, and essentially was made a scapegoat for the tragic loss of the army. However, after the fall of the Communist regime, he was rehabilitated and increasingly seen as a heroic figure, embodying Hungarian military virtue. Gusztáv Jány upheld his military oath steadfastly, shared the fate of his soldiers, and did his best to save his comrades. The next step to fully restore his honour and reputation would be to restore his military rank posthumously.