The people of two German states went to the polls this Sunday, 1 September. Elections for the state parliaments were held in Saxony and Thuringia, about a year before the German federal election is set to take place in September 2025. Mathias Corvinus Collegium’s (MCC) German-Hungarian Institute held an event to look at what could be expected and to make some predictions.

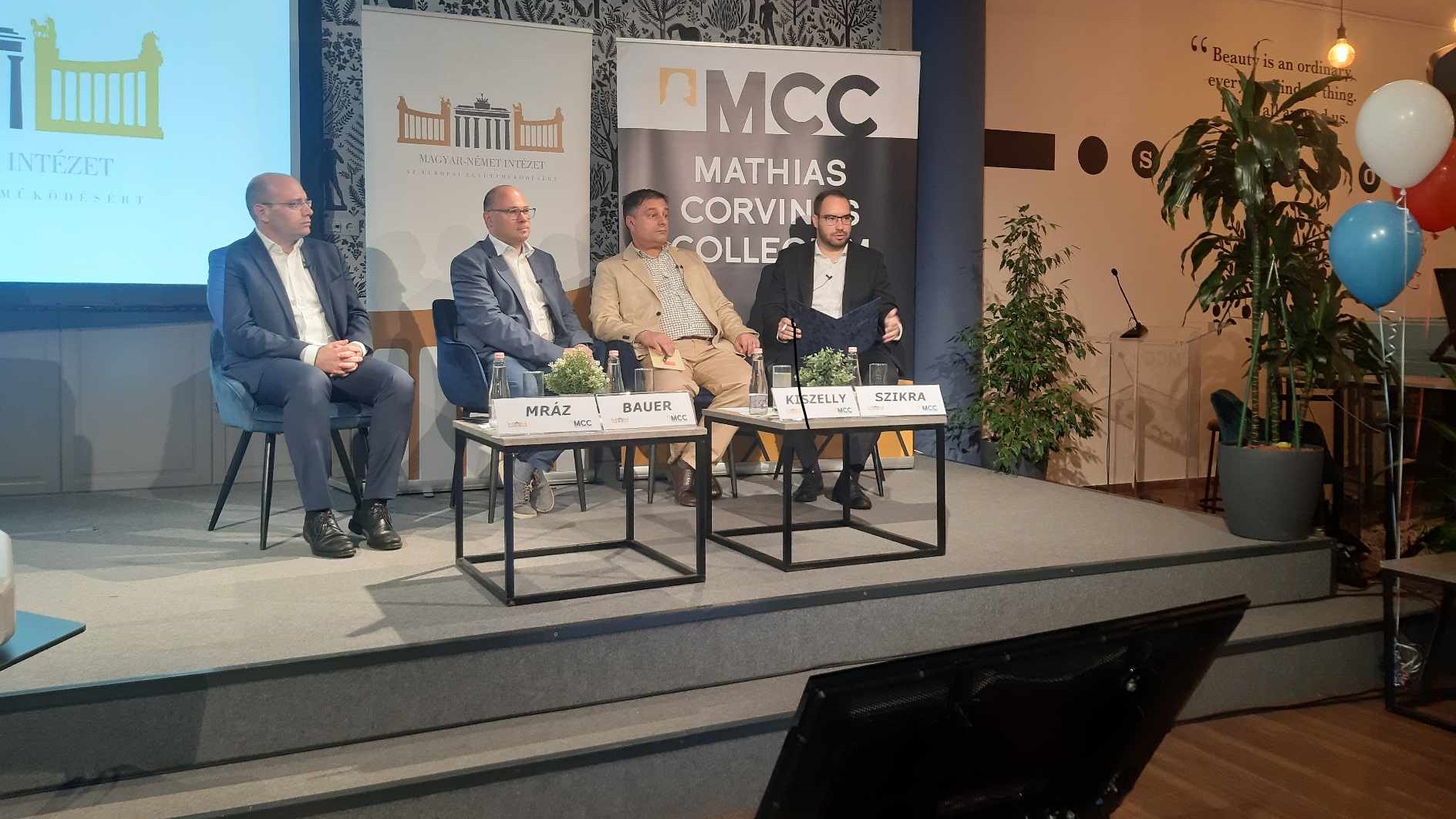

Bence Bauer, Director of the German-Hungarian Institute explained in his opening remarks that the Collegium has been hosting panel discussions for each major political event in the past year, such as the Polish elections, the European Parliamentary elections, or the French special elections. This time, it was the German state elections on the schedule. The event took place at MCC Scruton, the café located on the premises of MCC’s Budapest campus, on the afternoon of the elections.

Mr Bauer also explained that in many ways, state elections are more important in Germany than federal elections. The big question of the night, as he pointed out before the results came in, was whether or not the German establishment would manage to contain right-wing populist AfD in a ‘political quarantine’.

He also reminded that this was the eighth election in both states since the unification of East and West Germany in 1990.

Ágoston Sámuel Mráz, CEO of the Hungarian polling and research firm Nézőpont Institute (Nézőpont Intézet) and Zoltán Kiszelly, the director of political analysis for the Századvég Research Center joined Mr Bauer for the panel discussion about the elections, which started before the results came in, but followed the live updates from the German state television of the vote count after about an hour into the discussion. Levente Szikra of the Center for Fundamental Rights served as the moderator.

Mr Mráz started by reminding all that the candidate selection for next year’s federal election is starting soon, giving these state elections even more weight. He went on to opine that in today’s election,

‘the failure of the German migrant policy is on full display,’

with the recent migrant attacks in the country fuelling AfD’s support. He also pointed out that the German elite as a whole went on a full-on attack against the far-right party, with local bishops releasing a joint statement that no Christian should vote for them, and so-called ‘economic experts’ warning that the German economy could collapse if they got into power.

Mr Mráz also spoke of the recent strengthening of migration laws in Germany, some of which he found quite comical. For example, the German government now forbids people with asylum requests granted to go back to their home country for holiday—which happened quite often despite the fact that these people supposedly fled from grave dangers in their countries…

Mr Bauer commented on the same topic. Recently, just before the elections in Saxony and Thuringia, 28 Afghan criminals were deported from Germany at last. Chancellor Scholz has also vowed to increase and speed up deportations, which Mr Bauer believes, is still not enough to solve the problem. He also pointed out that the current SPD-led administration has a record-low approval rating right now.

Mr Kiszelly said he thinks the German leadership still views mass migration as the solution for their demographic problems, so, despite the recent public rhetoric, he expects no long-term change in their policies, only minor concessions for temporary political gain. He also pointed out that AfD holds radically different views from the German mainstream not just on migration, but on the Russo-Ukrainian war as well. They also serve as a ‘protest vote’ for those who do not necessarily agree with them, but want to show their discontent with the current state of affairs in the country, In that way, they are similar to Geert Widler’s PVV party in the Netherlands, who won the special election in 2023, but failed to form a coalition with Wilders as the Prime Minister.

Mr Mráz spoke up again, saying that there is a good reason to be discontent in Germany right now, as the country has been in a recession for four and a half years. He also pointed out that in the former East German state of Thuringia, the population is very friendly to the Russians, given the generations of communist indoctrination, thus AfD’s war policy resonates there a lot more than in other parts of the country.

Then, the exit poll results for the elections in Saxony and Thüringen were released.

AfD ended up winning in Thuringia with around 33 per cent of the popular vote (these are tentative results), with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) coming in second place with 24 per cent, the far-left BSW party coming in third with 15.5 per cent, the centre-left Die Linke party coming in fourth with 13 per cent, and the socialist SPD party, the party of the incumbent Chancellor, getting just six per cent (!) for fifth place.

In Saxony, CDU won with around 32 per cent, narrowly beating out AfD with 31 per cent. BSW finished third there too, getting 12 per cent, while SPD got 7.5 per cent of the vote in the state.

End Wokeness on X (formerly Twitter): "BREAKING: AfD becomes largest party in Thuringia, 2nd largest in Saxony 🇩🇪 A massive defeat against globalism pic.twitter.com/IH1HFe3WAB / X"

BREAKING: AfD becomes largest party in Thuringia, 2nd largest in Saxony 🇩🇪 A massive defeat against globalism pic.twitter.com/IH1HFe3WAB

These results were by and large what was expected, so they did not shift the tone of discussion.

Mr Bauer noted that the two parties on the opposite ends of the political spectrum, BSW and AfD, could form a majority coalition in Thuringia, which was a possibility given that both are anti-establishment. Mr Márz, however, claimed that this is unlikely. He also spoke of how he believes these results reflect on the federal election next year.

He thinks that, just like US President Joe Biden, Chancellor Scholz may not be his party’s nominee in the next election either. It may be Minister of Defence Boris Pistorius instead, who remains quite popular in the country. While there were rumours about a possible draft bill passing, he believes that may not happen to keep Minister Pistorius’ favourability high. Mr Mráz also thinks that Friedrich Merz of CDU has a very good chance of winning next year’s election, and becoming the next German chancellor.

He also spoke of the possibility of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany banning AfD, which it has the power to do. It last banned two radical parties in the 1950s, as the expert pointed out. It remains to be seen if the German establishment will go that far with a popular anti-globalist, right-wing party on the rise.

Related articles: