Since ancient times, foreign policy has been like stepping into a river: we never step into the same water twice. Foreign policy is the art of following changes, but we need to know just what has changed and by how much, and who wins or loses as a result. Given that the last quarter of a century or so has seen the emergence of increasingly complex interstate relations around the globe, ever fewer events can be seen as having merely a local, limited impact. The era of stagnant water ended a long time ago, and even then, looking back, we can observe that there were tectonic movements during those periods too, it is merely that they are more difficult to observe, and are generally recognized only in retrospect. Over the last decade, however, structural changes have emerged in rapid succession in the global system of international relations, in the world economy, and in global communication. Sometimes the wind has blown from the west, sometimes from the east, sometimes from the north, and sometimes from the south; on some occasions it has brought storms, on others calms, sometimes a pandemic, at other times a tragic war.

Some Thoughts on the Hungarian Perception of the Turkic Past

A search for the roots of the Hungarian people leads us eastward, to the Volga region, Western Siberia, the western reaches of Central Asia, the North Caucasus and the southern zone of the Eastern European steppe; a geographical region which for millennia witnessed Eurasian turmoil, with Uralic/ Finno-Ugric, Indo-European/Iranian, AltaicTurkic, and Paleo-Siberian languages and their associated peoples mixed and intermingled. It was during this process, perhaps as early as the fifth century bc, that the Hungarians became a distinct nomadic people. At least two centuries of research into Hungarian prehistory has clearly proven that the linguistic, anthropological, social organization, and cultural roots of Hungarians come from different backgrounds. In many cases, it is almost impossible to resolve linguistic, archaeological, and historical contradictions. This explains why so many elements of Hungarian prehistory are lost in the mists of time, and why it has proved such a popular area for amateur speculation.

The Hungarian language has a Uralic/ Finno-Ugric base, but the ancestors of the Hungarians had intermingled with Western Turkic tribes since very early times, and this memory left a deep mark in our language, primarily through many loan words.1 Today, the only survivors of this Western Turkic linguistic environment are the Chuvash, who inhabit an area of Russia to the south of Moscow. The conquering Hungarians were, as a result of various fusions, Turkic in their anthropology, and their pre-Christianculture was also determined by their Turkic— primarily Khazar—heritage, while their musical roots lead back to the Volga Turks and the northern Turkic world.2

The Hungarians were one of the tribal confederations that travelled the east–west migration route stretching from the Dzungarian Gate (now on the western border of China) to the Carpathians. These migrations began in the fourth century AD with the appearance of the Huns on the banks of the Danube, and successive waves continued to arrive until the occupation of Eastern Europe by the Mongols in the thirteenth century.

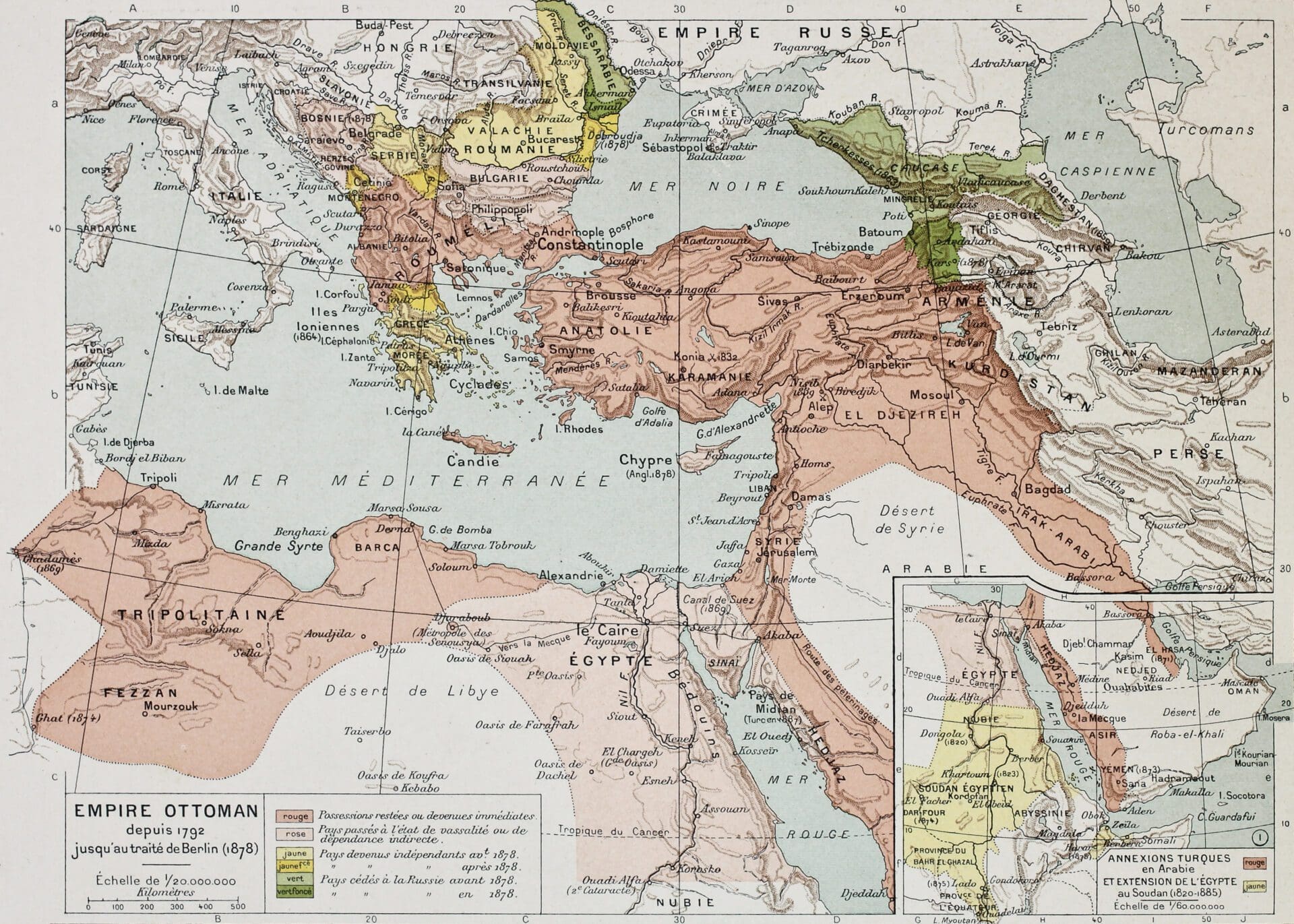

The present contours of central Eurasia only began to take shape as a result of Russian colonization from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries.

We cannot discount the possibility that some scattered Hungarian groups, or tribes living in close contact with the Hungarians, appeared in the Carpathian Basin together with the Huns and Avars, several centuries before the Hungarian conquest in the late ninth century. What is certain is that, at the turn of the ninth and tenth centuries, the conquering Hungarians found a number of ethnic groups in the Danube–Tisza region whose culture, ethnography, and lifestyle were almost identical to their own. Since there are no relevant written records from this period, it is impossible to say with any confidence what languages were spoken.

The Carpathian Basin, which from the tenth century on became the homeland of the Hungarians, welcomed and integrated a number of migrating Turkic peoples between the tenth and thirteenth centuries: these included the Pechenegs and the Oghuzes, and, fleeing before the Mongols in the thirteenth century, the Cumans, who formed the westernmost branches of the Turkic-Kipchak linguistic and social community that stretched from Central Asia (modern Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan) across the southern part of the Eastern European Plain (via the Nogai and the Crimean Tatars) as far as the Great Hungarian Plain. The Mongol invasion and the establishment of the Golden Horde in the second half of the thirteenth century—as a result of both necessary military defence measures and the Mongol migrations taking place in the region—permanently closed Hungary off from the Eastern European Turkic world. But even in the rapidly westernizing Kingdom of Hungary, home to Central European and Western settlers, the Turkic cultural heritage survived almost down to the present day in material and intellectual folk culture, especially pastoral folk art and folk music, but also in Hungarian folklore. From the Middle Ages down to the modern era, the Hungarian nobility considered themselves to be of Turkic origin, and considered the royal house of Árpád to be the descendants of Attila or his sons.3

The almost six centuries of Hungarian relations with the Ottomans paint a two-sided picture. The wars that began at the end of the fourteenth century ended only at the beginning of the eighteenth century. These proved fatal for the Hungarians. The once powerful Kingdom of Hungary lost its national sovereignty during the first third of the sixteenth century—primarily as a result of its defeat at the Battle of Mohács in 1526 and the death of King Louis II—and only regained it in 1918. Hungarians were suborned to the interests of the Habsburgs on one side and Ottoman foreign policy on the other, and the central core of the country, together with its ancient capital of Buda, became Ottoman Turkish territory for nearly a century and a half. Fighting alongside the Habsburgs, the Hungarians in the north and west of the country halted the Ottoman advance, while those in the east formed the Principality of Transylvania, nominally independent but a vassal of the Ottomans. The defeat of the Ottoman Turkish army which besieged Vienna in 1683, and the resulting Habsburg campaign in Hungary, led to a major turning point in the history of the Carpathian Basin, and by the treaties of Karlowitz (1699) and Passarowitz (1718) the entire territory of the Kingdom of Hungary was freed from Ottoman rule.4

From the beginning of the eighteenth century, the relationship between the Hungarians and the Ottomans changed, and for three centuries the Ottomans became the devoted—often indeed the only—supporters of Hungary’s struggle for freedom from Vienna. They also gave refuge to thousands of fleeing Hungarians. During the First World War, Hungarian soldiers fought for the Ottoman Empire, and Ottoman-Turkish troops fought for the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. But

at the end of the war, the Hungarians and Turks both found themselves the victims of the Entente’s peace-making efforts.

Hungary accepted the Treaty of Trianon, by which it lost much of its territory, but the Turks took up arms against the Entente diktat imposed upon them, and thanks to their victories, they were able to preserve their ethnic borders. The leader of this struggle, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was always considered a hero by the Hungarians.5 The relations between Budapest and Ankara were excellent during the interwar period, and one of the uplifting memories of this is that Prime Minister Miklós Kállay, who defended Hungarian national sovereignty with all his might, was given diplomatic protection at the Turkish Embassy in Budapest during the German invasion of Hungary on 19 March 1944.

The Cold War put an end to Hungarian– Turkish friendship: Budapest’s relations with Ankara could develop only in accordance with Moscow’s interests. One consequence of the events of 1989–1990 was that a new chapter in Hungarian–Turkish relations could be opened, while the dissolution of the Soviet Union meant that Hungarian diplomacy could develop closer relations not only with the Turkish, but also with the Turkic world.

Varietas Delectat

Hungary has been a bastion of the West for a thousand years, and an integral and integrated part of it, together with other states in the region—possessing the characteristics that Jenő Szűcs summarized in his study ‘Vázlat Európa három történeti régiójáról’ (A Sketch of Europe’s Three Historical Regions) in the 1979 István Bibó’s Memorial Book, with an argument that is still valid today. Essentially, he argued that the great Western, Central, and East Central European traditions were built on strong structures, values, and traditions, within such a sturdy framework that the Soviet system could only weaken and suppress them, but could not destroy them.

The Hungarian and East Central European democracies sprang up at the end of the 1980s from this intellectual and political memory,

as well as from favourable changes in the international political situation. Central Europe—like many large world regions—has undergone huge changes in the last three or four decades, as part of a historical journey. Though Europe was divided into tacit spheres of influence at the end of the Second World War, the Western influence (and from the 1990s the Euro-Atlantic influence) has returned. Within this new historical situation, over the last three decades the Central European nations have preserved their own regional and national traditions, which the Soviets once sought to trample underfoot, even while successfully transforming and catching up economically with Western Europe. The fact that this is not understood, or is misunderstood, in some centres of the Western world calls into question the idea of European diversity, stretching from Andalusia to the Baltic, from the wonderful Greek islands to Scotland. However, if we look into the well of history, as Thomas Mann conceived it, we can see that this has happened many times before, and history has continued on its way, with everything sometimes turning out for the better, sometimes for the worse. We might also quote Thucydides, who noted that human nature never changes: there are certain kinds of people, certain kinds of politicians, certain kinds of states, and certain kinds of alliances. We should not judge one by the standards of another, though unfortunately it can happen when we are truly threatened politically, economically, or militarily. However, we should keep it before ourselves at all times, varietas delectat.

In the Middle Ages, Hungarian foreign policy had to focus on developments in a number of different directions, and to assess which were the weightiest and most consequential. It is no different today. From our perspective, we have no opportunity to take stock of the twenty-first century. Posterity will do that for us, since by then it will have become clear which were steps in the right direction, which were mistakes, and which were merely diplomatic faux pas or instances of insensitivity. In this article, we shall review just one segment of Hungarian foreign policy, its policy towards Turkic states, which is at times misinterpreted or mishandled in Hungarian and international public discourse.

The Turkic World as an Independent Geo-Cultural and Geopolitical Force

Globally, according to the calculations of Turkologists, nearly 300 million people speak 41 different Turkic languages, from the Lower Danube to the Pacific Ocean and from the Arctic Ocean to the mountains of Afghanistan.6 Slightly more than half of them live in a country whose state language is Turkic: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Türkiye, and Turkmenistan. The remainder live in states where the official language is not Turkic. Most live in the Russian Federation, China, or Iran, but they are spread across dozens of other states.

Ever since the historic changes of 1991 culminating in the collapse of the Soviet Union, five Turkic states have had the opportunity to pursue an independent Turkic foreign policy: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. Though in 1991–1992 their ministries comprised only a few dozen diplomats,

they now employ more than a thousand people, and all have established excellent diplomat training institutions.

Over the past decade, Baku, Nur-Sultan, Tashkent, Bishkek, and Ashgabat have successfully taken advantage of Ankara’s professional, open-to-the-world diplomacy, with a centuries-old foreign policy tradition.

The initiator of comprehensive pan-Turkic cooperation was the late Turkish President Turgut Özal (1927–1993), who, in 1992, recognizing the new opportunities arising from the process of Soviet disintegration, launched the annual meetings of heads of state. This led to the establishment of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States (Türk Dili Konuşan Ülkeler İşbirliği Konseyi) in 2009 in Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan, by Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Turkish diplomats, to facilitate closer intergovernmental cooperation. In 2019, Uzbekistan also joined the council. In 2020, the heads of state gave the organization a new name—the Organization of Turkic States (Türk Devletleri Teşkilatı)—to better express the new aspirations of the organization, which aim to achieve deeper political, economic, and cultural integration, in a specific step-by-step implementation process that is sure to last several decades at the least.7

Today, the Organization of Turkic States is a form of intergovernmental cooperation in which heads of state and government commit to coordinating the policies of their respective countries based on shared interests across a vast geographical area stretching from the Altai Mountains to the eastern basin of the Mediterranean Sea. The Organization of Turkic States is now an indispensable geopolitical, economic, and geo-cultural intergovernmental cooperative association within the international relations system.

Hungary, the EU, and the Turkic World

Every member state of the European Union maintains important relations with the Turkic world, purchasing large quantities of raw materials, agricultural products, and manufactured goods from there. From a geographical perspective, meanwhile, the area to the east of the Stockholm–Hamburg–Munich– Rome line is more important, given transport routes and economic relations, than the area west of it. Hungary is located in the former region, and its interests naturally necessitate productive economic relations with Türkiye, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan; in other words, with the dominant states of the Turkic world, to whose peoples we are bound by many threads due to our history, language, and culture. Hungary has long been a well-known state in the Turkic world, and this has traditionally been a great advantage in opening doors for diplomats from Budapest, but of course, this only works smoothly if it operates on a basis of reciprocity. There is no reason why this should not be the case.

Hungary has been an observer state within the Organization of Turkic States since 3 September 2018. Naturally, this did not happen by accident. The leaders of the Turkic states have always greatly appreciated the attention paid to them by successive Budapest governments since the political transformation of 1990. In 2022, we commemorated the fact that thirty years ago, together with several members of the international community, we officially recognized the independence of Azerbaijan and the Central Asian states. Recollecting this, it is evident that

Hungary was among the first to extend the hand of friendship to these newly independent states.

On 3 March 1992, we established diplomatic relations with Uzbekistan, on 2 April with Kazakhstan, on 17 April with Kyrgyzstan, on 27 April with Azerbaijan, and on 11 May with Turkmenistan.8 But history also reminds us that the Republic of Türkiye, which was established on 29 October 1923, signed its first international treaty, the Treaty of Friendship (Muhadenet Muahedenamesi/ Dostluk Antlaşmaşı) on 18 December 1923— making it an approaching centenary—with the Kingdom of Hungary.9 Hungarian foreign policy, when it has been free to follow its own principles, either during the 1919–1941 period or thanks to the restoration of Hungarian foreign-policy sovereignty in 1990, has traditionally been open to the Turkic world. A fuller treatment of these relationships lies outside the scope of this essay, but there can be no doubt that we have much to commemorate and to celebrate.

After the events of 1989–1990, Hungary spent at least two decades searching for its new place in both the Euro-Atlantic world and in Central Europe. Up until the 2010s, successive Hungarian governments considered the former as a priority. The opportunity to reassess Hungarian foreign policy arose only after 2010, when, in addition to the existing Euro-Atlantic and Central European priorities, Budapest began to adapt diplomatically to global trends, and announced a global opening. Building comprehensive relations with the Turkic world became one area of particular success. Within this framework, Hungary has signed bilateral international treaties on strategic partnership with Azerbaijan (11 November 2014), Kazakhstan (3 July 2014), Kyrgyzstan (29 September 2020), and Uzbekistan (30 March 2021).

Hungarian diplomacy has traditionally fostered ties with various inter-Turkic organizations, including the Ankara-based International Organization of Turkic Culture (Uluslarası Türk Kültürü Teşkilatı, TÜRKSOY), the Baku-based Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic-speaking States (Türk Dili Konuşan Ülkeler Parlamenter Asamblesi, TÜRKPA), the Nur-Sultan-based Turkic Academy (Uluslarası Türk Akademisi), and the Baku-based Uluslararası Türk Kültürü ve International Turkic Culture and Heritage Foundation (Mirası Vakfı). These institutions, each of which specialize in particular fields, all operate under the oversight of the Organization of Turkic States, though of course they have independent decision-making powers. In 2014, Hungary signed a cooperation agreement with TÜRKPA and the Turkic Academy, and became an observer member of these institutions. During this period, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán made several successful visits to Turkic states. It was in connection with this that the heads of state of the Turkic Council invited Prime Minister Orbán as a guest to the sixth Cholpon-Ata Summit, held on 3 September 2018, during the Kyrgyz presidency—the event at which Hungary was offered observer membership. This was the first time in the history of the council that such an expansion had taken place. It was thus both an honour and an opportunity for Hungary to establish a new kind of relationship structure.

For the Turkic world, meanwhile, the opening of new doors to Hungary also meant an opening towards Central Europe and the EU as a whole. This presents Hungary with the estimable task of bringing the politics, economy, and culture of the Turkic world closer to Central Europe and the EU, as a new bridge country, while at the same time building closer bilateral ties.

It is likewise gratifying that in recent years the relationship between the European Union and the Central Asian states and Azerbaijan has also strengthened, especially through the signing of Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (EPCA), which the EU has so far signed with Kazakhstan, on 26 October 2015, and Uzbekistan, on 6 July 2022, and may sign with Kyrgyzstan at the end of the year. Azerbaijan became one of the key countries in the EU’s Eastern Partnership through the signing of the Partnership and Cooperation Treaty on 22 April 1996. Despite this, in the developments this cooperation has fostered, Azerbaijan has tended to lose out. Now, however, thanks to its geo-strategic and economic importance, the time has come for Azerbaijan to finally benefit from these developments; something, incidentally, that the president of the Council of Europe, Ursula von der Leyen herself emphasized during her visit to Baku on 18 July 2022.10 During the visit, the ‘Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership in the Field of Energy between the European Union and Republic of Azerbaijan’ was signed by the president of the European Commission and the president of the Republic of Azerbaijan as a document recognizing the significance of the strategic energy relations and cooperation between the sides as a key factor contributing to open, competitive, diversified, and secure energy markets. Accession negotiations between the EU and Türkiye stalled in 2016, but

Turkish diplomacy has maintained extensive cooperation with the EU despite numerous disputes.

It is time, especially given the current political, military, and economic crises, for Brussels and Ankara to place their relations on a new footing.

The Organization of Turkic States

The member states of the Organization of Turkic States have a combined population of 156 million people, and cover a total area of 4.2million square kilometres, which is roughly the same size as the EU. It is by no means easy to coordinate and harmonize political and economic processes over such a vast geographical area. This extremely difficult work is the responsibility of the General Secretariat in Istanbul. In 2009 the General Secretariat began its coordination work, in which the diplomats of each affected state takepart according to a previously agreed quota. The head of the organization is the secretary general, who has a three-year mandate, and appointment follows the country names in alphabetical order according to the Latin alphabet. The current secretary general, Baghdad Amreyev, is a Kazakh diplomat, who will be succeeded by a Kyrgyz diplomat. The presidency is held by countries, and rotates on an annual basis. Türkiye currently holds the presidency, and will hand it over to Uzbekistan in November 2022, which will in turn be followed by Kazakhstan in 2023. Since 2021, the other observer member of the organization has been Turkmenistan. The General Secretariat of the Organization of Turkic States in Istanbul has operated a Representation Office in Budapest sinceSeptember 2019, where one diplomat from each member state serves together with the Hungarian office staff. The RepresentationOffice is an important tool to help Hungarian diplomacy promote inter-Turkic cooperation, and to aid these states in seeking out new opportunities within the EU as well.11

The establishment of the Organization of Turkic States two decades ago was in many ways a response to the new political, economic, and cultural challenges that were emerging at the beginning of the twenty-first century. But it is also true that by this time

the demand for vertical political, economic, and cultural cooperation had already become a vitally important part of the international relations system.

Behind these cooperative efforts among states with common roots lay the impulse to form a new centre of gravity in the world economy and international relations, to better serve their interests. This would allow them to occupy a more favourable position within the web of global networks that enmeshes them in relationships of cooperation and dependence, and which offers many opportunities, while at the same time forming obstacles to their national development or political objectives.

Reflections on the Formation of Common Turkic Identity

The common Turkic sense of origin is the result of the self-consciousness which arose across the large geographical area stretching from the Balkans to the Altai and from the Volga region to the eastern reaches of the Taurus Mountains, and which in the second half of the nineteenth century gave new impetus to the political, economic, and cultural aspirations of the peoples living here, while at the same time their sense of a common identity became one of its core tenets. The germs of national feeling, popular consciousness, and linguistic and cultural awakenings all appeared contemporaneously, seeking to find a place within the Ottoman Empire and Tsarist Russia at a time when industrialization, railway construction, oil mining, and modern journalism were all spreading. At that time, all Turkic languages used the Arabic script, and the text of newspapers was widely understood everywhere, because vowels were generally not indicated in the printed Arabic script. This meant that a newspaper published in Crimea could also be read in Central Asia, as could the journals of the Ottoman Empire. The increasing interconnectedness of the Turkic world from the middle of the nineteenth century launched modern Turkology, the academic research of individual Turkic languages and cultures, and their teaching at universities; a discipline in which Budapest—where, though under various names, the world’s first Turkology Department has been operating since the 1870s—has a distinguished place.12

The Turkish—with the Young Turk Revolution of 1908—were the first among the Turkic peoples to embark on a new path of national development, which came to fruition in their national struggle of self-defence following the First World War (1920– 1923), ending the Ottoman imperial era. In the former Russian Empire, meanwhile, the Bolsheviks made many promises to the national movements that had sprung up in the Caucasus, the Volga region, and Central Asia, to win them over. This policy was largely successful, and they were able to establish themselves in these regions. When Soviet rule had become sufficiently entrenched, however, the Turkic national movements were Sovietized, and at the same time, the nomadic and semi-nomadic social structure, which had been an important means of maintaining their cultural identity, was destroyed. The larger Turkic peoples were given the status of member republics in the Soviet Union, within somewhat artificial borders. Soviet colonialism brought both industrial development and a loss of national self-consciousness. The development of the national languages did not receive any support, the self-consciousness of the Turkic community was relegated to the corners of university classrooms, and during the decades of the Cold War it could be spoken of only in whispers.

The Turkic elite of Tsarist Russia, whether from Central Asia, the Volga, or Crimea, could travel to Istanbul and from there to various cities of Europe, including Paris, Berlin, and Budapest. The Soviet Union did not allow such cross-cultural opportunities, and thus meaningful international Turkic cooperation was made difficult or even impossible, even in the sciences, until the end of the Cold War. The situation was such that even scholarly books on Turkology had to be smuggled out of Türkiye via Budapest, East Berlin, and Warsaw to Central Asia and Azerbaijan, as well as to research institutes in Moscow. Valuable packages of books from Turkic scientists in the Soviet Union also arrived in the universities of Istanbul and Ankara by this route. International Turkology, a discipline which included many Hungarian scholars, regularly broke through the barriers of the Cold War by holding scholarly conferences that were attended by people from both sides of the Iron Curtain. Two Hungarian Orientalists—Denis Sinor from Indiana University and György Hazai from Humboldt University in Berlin, with a sort of Cold-War Hungarian wink—managed to organize the first real East–West Turkologist– Altaist meeting in East Berlin in 1969, at the Permanent International Altaic Conference (PIAC), which can boast of continuous, effective operation down to the present day.13 However, scholarship is only a small part of everyday life, and the better, more comfortable part.

In terms of political, social, and economic relations, the Turkic world followed two diametrically divergent models.

In the Soviet Union, they trusted in the communist, centrally planned economic policy, which by the 1980s had decisively failed. In Türkiye, meanwhile, a Western-style market economy was introduced in the 1980s, which gave the Turkish economy a drive and dynamism that it has retained to this day. Thus, after the Cold War, there was plenty to admire in the Turkic world.

The Most Important Strategic Issues of Turkic Cooperation: the Middle Corridor and Its European Aspects

Azerbaijan and the Turkic states of Central Asia, which gained their independence in 1991, looked to Türkiye as a model, but it soon became clear that, due to their different historical paths, it would prove difficult to connect the gears of the Turkic world. Even today, many divergent forces operate across the vast area from the Altai Mountains to the Mediterranean Sea, marking the bitter imprints of past centuries, and are often the relics of great-power arrogance, the internalization of external post-colonial interests, or simply the extinguishing of local/national/tribal self-awareness during the time of Russian/Soviet empire building. Eurasian networks (the Eurasian Economic Union, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization) provide the Turkic world with new opportunities only to a limited extent, since the Turkic states must find the best modus vivendi between the huge and resourceful People’s Republic of China and the strong Russian Federation, which dominates Eurasia’s energy sector.

In 2020, the Organization of Turkic States announced a new Turkic integration initiative, involving closer cultural and economic cooperation between politically connected Turkic regions. However, the effectiveness of all this can be ensured only if the countries of the region are able to create a new transport and transit infrastructure. This should also be part of the New Silk Road (One Belt One Road/Belt and Road Initiative) connecting Western China with Europe and the Indian Ocean, announced and begun by the People’s Republic of China in 2013, including what the literature dealing with the issue calls the ‘Middle Corridor’, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route.14

The transport and delivery corridor connecting Central Asia and present-day Türkiye crosses the Caspian Sea (from Kazakhstan to Azerbaijan) and the Caucasus (via Azerbaijan and Georgia). This was also partially the case in the Middle Ages, during the heyday of the Silk Road, when caravans transported various goods from the Turfan Depression to the Balkans, and to Italian merchant ships on the Black Sea coast. This extremely important overland network, the route of which is now marked by ruined cities and abandoned caravanserais, was weakened and then destroyed by the great global economic reorganization—due to the transfer of world trade routes to new geographical areas—in the second half of the sixteenth century. Caravan trade could not compete with maritime trade. For at least three centuries, Indian and Chinese goods reached Europe via the Indian and Atlantic oceans, as a result of which first the Portuguese, then the Dutch and later the British grew rich. Under these conditions, the vast Central Asian and Western Asian regions, as well as the Balkans and East Central Europe, faced several centuries of economic decline, impoverishment, social and economic stagnation, and, consequently, very limited development.

The development of railways created new trade routes in the nineteenth century, offering new opportunities for land transport, and

many large regions of the world were able to break out of their peripheral or even isolated positions in the world economy.

However, the railway lines were not built based on the interests of the Turkic peoples, but rather according to the current state of the Great Game15 between Russia and Great Britain, in which the Ottoman Empire was sometimes also dealt a card, especially from the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries on, when Germany sought to further its imperial interests and project Berlin’s power even as far as British India through a direct railway link to Baghdad.16 A transit corridor across the Caucasus was not in the interest of any great power, and indeed the violent rivalry between the Ottoman and Russian empires naturally made such a link inconceivable. The Caucasus region could only become an East–West corridor after the disintegration of the Soviet Union. As long as the Soviet empire was in existence, Moscow had no interest in allowing the transport route for Baku oil, Central Asian mineral resources, and agricultural products to run south of the Eastern European Plain to the Black Sea and/or northern Anatolia. Change could only begin in 1992, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union the previous year.

However, even today, the realization of this goal still presents challenges for the Turkic world and the other peoples of the Caucasus. There is no question that this is the biggest challenge for Turkic cooperation in the twenty-first century. But it is also much more than that. The Russian–Ukrainian War that began in February 2022 has highlighted that the EU also desperately needs the Caspian–Caucasus corridor to replace the transport routes across the plains of Northern Russia and Eastern Europe. In recent years, the Aktau–Baku ferry connection (the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route) has been established on the Caspian Sea, and the development of its intersectional nodes is progressing at full speed. After a decade of work, the Baku– Tbilisi–Kars railway line across the Caucasus has been renovated or built from scratch, and road transport infrastructure is being developed in parallel with it.

Chairman of the Council of Elders of the Organization of Turkic States Binali Yıldırım (who was prime minister between 2016 and 2018) has overseen huge Turkish railway development work over the last two decades, and in 2016 the Eurasia Tunnel was opened, which allows rail transport to take place between the two sides of the historical strait without trans-shipment. Railway wagons departing from Baku now have a new way of reaching Europe. The goods launched from Baku can also be loaded onto a ship in Trabzon, so that they can continue their journey by sea from there. These are huge achievements, and the expansion of these capacities is of particular interest to the Turkic world and to Europe. Of course, serious improvements are also needed on railway lines in the Balkans. If this happens, however, Budapest will become the ideal hub for goods transported overland from Central Asia, while of course goods can also be transported from west to east by the same system.

The Russian–Ukrainian War and its consequences have increased the value of the oil and gas reserves in the Caspian region.

The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline is already sixteen years old, while the Trans- Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) was completed in 2018. One branch of this, the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) leads to the boot of Italy, through which Azerbaijani gas reaches the European networks, as well as, of course, through other auxiliary gas transfer systems. Only now is it truly apparent how big a mistake it was for the EU not to give sufficient support to the Nabucco Plan, which could have supplied Central Europe with a sufficient amount of gas from Azerbaijan, Iraq, and Turkmenistan, and instead to let this great plan expire in 2013. Now we are living with the consequences. This should not be forgotten, at least in the scholarly literature of international politics.17

Visions of the Future and the Importance of the Turkic World

Across the Eurasian landmass, on which the Turkic states are located, centripetal forces are currently acting as counterweights to the effects of challenges and external pressures, strengthening Turkic cooperation and the cohesion of the Organization of Turkic States. These states are conscious of the geopolitical situation that has developed in recent years, and their geostrategic responses realistically take into account the Eurasian role of China and Russia, their global economic capabilities, and also their importance in the global world order in the short, medium, and long term. This does not mean that the Turkic world is willing to shut itself off in Eurasia; on the contrary, they strive for openness towards the EU, the Middle East, Iran, the Indian Ocean region, as well as South Korea and Japan. They are aware of the global political weight and power of the United States, and also of the Indo-Pacific Strategy’s overtures towards them. Türkiye is the coastal window of the Turkic world, as well as a special transport hub to any part of the world, which is well known in Azerbaijan and Central Asia.

The Russia–Ukraine War—despite the emerging international crisis—has led to increased appreciation of the Turkic world. For this huge region, which is horizontally extremely affected by the crisis, the question of what policy it will follow in this new, post-globalist conflict is of the utmost importance. Will it close itself off, or will it commit to constructive mediation and crisis prevention? There can be no doubt that the capitals of the Turkic world are committed to the latter course. Since February 2022, the Turkic world has become more important to all global factions than it was before. The diplomatic threads of relationship building and strengthening from Moscow, Beijing, Washington, New Delhi, Tehran, and Tokyo are almost woven into the network of Turkic capitals. Nor is there any doubt that they are willing to follow different interests and different styles. For this, the EU and many of its important member states, especially Germany, France, Italy, and Poland, must prepare. After all, many different vectors meet in this huge geographical space, and can bring both good and bad results. That is why inter-Turkic coordination is extremely important in terms of the interpretation and management of challenges. The Organization of Turkic States, as the coordinating node of Turkic policies, must play a decisive role in this, strengthening its related capabilities and visibility.

The Turkic world plays a role in the supply of energy and raw materials in Eurasia—and perhaps even beyond.

However, the Turkic states cannot meet these obligations at a sufficient level with their current capabilities. They need complex structural reforms or conversion processes—as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have announced—through which they can not only improve their innovative capabilities, but also improve the quality and increase the quantity of their production. This follows from the rising demographic indicators of many Turkic states, but the import needs of the regions surrounding the Turkic world are at least equally important. The Turkic states can only achieve major economic transformation with international cooperation: through well-thought-out and reasonable loans, a sufficient level of technical expertise, and university and research collaborations. The member states of the EU must play a decisive role in this, but the decision-makers of the European states should perceive this more clearly than they currently do, and start implementing mega-projects.

Hungary is an accepted partner of the Turkic world, the reasons for which I have detailed in this article from several standpoints. There is no question that this will remain the case in the future. The intermediary role that Hungary holds can only be fully realized if our views and experiences are listened to at the global level. The doors we can and should knock on the most are in Brussels, as well as, of course, in Berlin, Paris, Rome, Warsaw, and other European capitals. The Visegrád Group—which, despite the current disputes, is the vertical essence of East Central Europe— should play a decisive role in this, starting as soon as possible. Incidentally, Warsaw will in all likelihood come to the same conclusion based on its own geopolitical perspectives and economic interests, while Prague’s and Bratislava’s very successful trade with the region should lead them in a similar direction. Budapest, meanwhile, is extremely interested in this initiative due to the successful opening towards the Turkic world.

It is worth noting, in the light of the Russia–Ukraine War, how the interests of the EU and the Organization of Turkic States align in so many areas.

Acknowledging this at a sufficiently profound level and translating it into Brussels policies is one of the remedies for the new economic crisis affecting so many countries around the world, and Europe particularly.

We are living through a period of major global crisis. It is at such time that one has to be open to the new, to discovering new export channels, to going beyond stuck policies that lead nowhere, and to escaping the golden cages of prestige, which have become diplomatic backwaters. One has to step into new rivers, whether fast-flowing torrents or muddy trickles, because they lead somewhere. Unfortunately, this will not bring peace between Moscow and Kyiv, but the strengthening of European–Turkic cooperation can help alleviate pain, stupidity, destruction, and the consequences that are rushing to the world like an ocean wave, and sometimes prevent them altogether. In today’s world, that is already something.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

NOTES

1 András Róna-Tas and Árpád Berta, West Old Turkic. Turkic Loanwords in Hungarian (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2011).

2 János Sipos, Comparative Analysis of Hungarian and Turkic Folk Music – Türk-Macar Halk Müziğinin Karşılaştırmalı Araştırması (Ankara: TIKA – Ankara Hungarian Embassy, 2006).

3 Gyula László, The Magyars. Their Life and Civilisation (Budapest: Corvina, 2017).

4 Pál Fodor, In Quest of the Golden Apple. Imperial Ideology, Politics and Military Administration in the Ottoman Empire (Istanbul: Isis Press, 2000).

5 János Hóvári, ‘The Emergence of the Turkish Political and Military Resistance to Great Britain and Its Allies (1919)’, in Ulrich Schlie, Miklós Lojkó and Thomas Weber (eds), Vom Nachkrieg zum Vorkrieg. Die Pariser Friedensverträge und die internationale Ordnung der Zwischenkriegszeit (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2020), 109–135.

6 Cf. Hendrik Boeschoten, ‘The Speakers of Turkic Languages’, in Lars Johanson and Éva Á. Csató (eds), The Turkic languages (New York: Routledge, 2022), 1–12.

7 Organization of Turkic States, ‘History of Organization’, accessed 8 September 2022, www. turkkon.org/en/organizasyon-tarihcesi.

8 Magyar Külpolitikai Évkönyv 1992 (Hungarian Foreign Policy Yearbook) (Budapest: Külügyminisztérium, 1992), 114.

9 Kövecsi-Oláh Péter, Török-magyar diplomáciai kapcsolatok a két világháború között (1920-1945) (Turkish–Hungarian Relations between the Two World Wars, 1920–1945) (unpublished PhD dissertation), 47–48. https://edit.elte.hu/xmlui/ static/pdf-viewer-master/external/pdfjs-2.1.266-dist/ web/viewer.html?file=https://edit.elte.hu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10831/40630/K%c3%b6vecsi- Olah_2018-09-17_JAV%c3%8dTOTT-converted. pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

10 ‘Statmenet by President von der Leyen with Azerbaijani President Aliyev’, European Commission, 18 July 2022, https://neighbourhood-enlargement. ec.europa.eu/news/statement-president-von-der-leyen- azerbaijani-president-aliyev-2022-07-18_en.

11 Organization of Turkic States, Representation Office in Hungary, ‘Turkic Council and Hungary’, accessed 8 September 2022, www.turkkon.hu/EN/news/ representative-office/.

12 Suzanne Kakuk, ‘Cent ans d’enseignement de philologie turque à l’Université de Budapest’, in Ligeti Lajos (ed.), Studia Turcica (Budapest: Akadémia, 1971), 7–27.

13 György Hazai, Against Headwinds on the Lee Side: Memoirs of a Passionate Orientalist (Berlin–Boston: de Gruyter, 2019), 83–84.

14 Naghi Ahmadov, ‘First Trilateral Meeting of the Ministers of Türkiye, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan’, Eurasia Daily Monitor, 19/107 (2022), https://jamestown.org/program/first-trilateral-meeting-of-the- ministers-of-turkiye-azerbaijan-and-kazakhstan/.

15 Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game. The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia (New York: Kodansha International, 1992).

16 Sean McMeekin, The Berlin–Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany’s Bid for World Power, (London: Penguin Books, 2011).

17 Joe Kirwin, ‘The Nabucco Failure: Juncker and Vestager Negligence Enhanced EU Dependence on Russian Gas’, The Brussels Times (21 March 2022), www.brusselstimes.com/211842/the-nabucco-failure- juncker-and-vestager-negligence-enhanced-eu- dependence-on-russian-gas.