The European Migration Crisis seems to have entered its second phase this year, precisely because of the Ukrainian war, the ensuing energy and food security crisis, and the consecutive global financial upheaval that caused tens of thousands in the Middle East and Africa to leave their homes and embark on the dangerous—and expensive—journey to Europe. We have already written about the situation at the Hungarian-Serbian border, where locals are reporting weekly gunfights between rival smuggler gangs that split up the entire length of the border fence and declared the Serbian side their own, privately controlled territory. The growing demand of tunnels under or openings in the fence not only drives profit but competition, too. As of early September, more than 160 thousand illegal entrants have been apprehended by Hungarian border guards this year, which is an almost threefold increase compared to last year’s numbers.

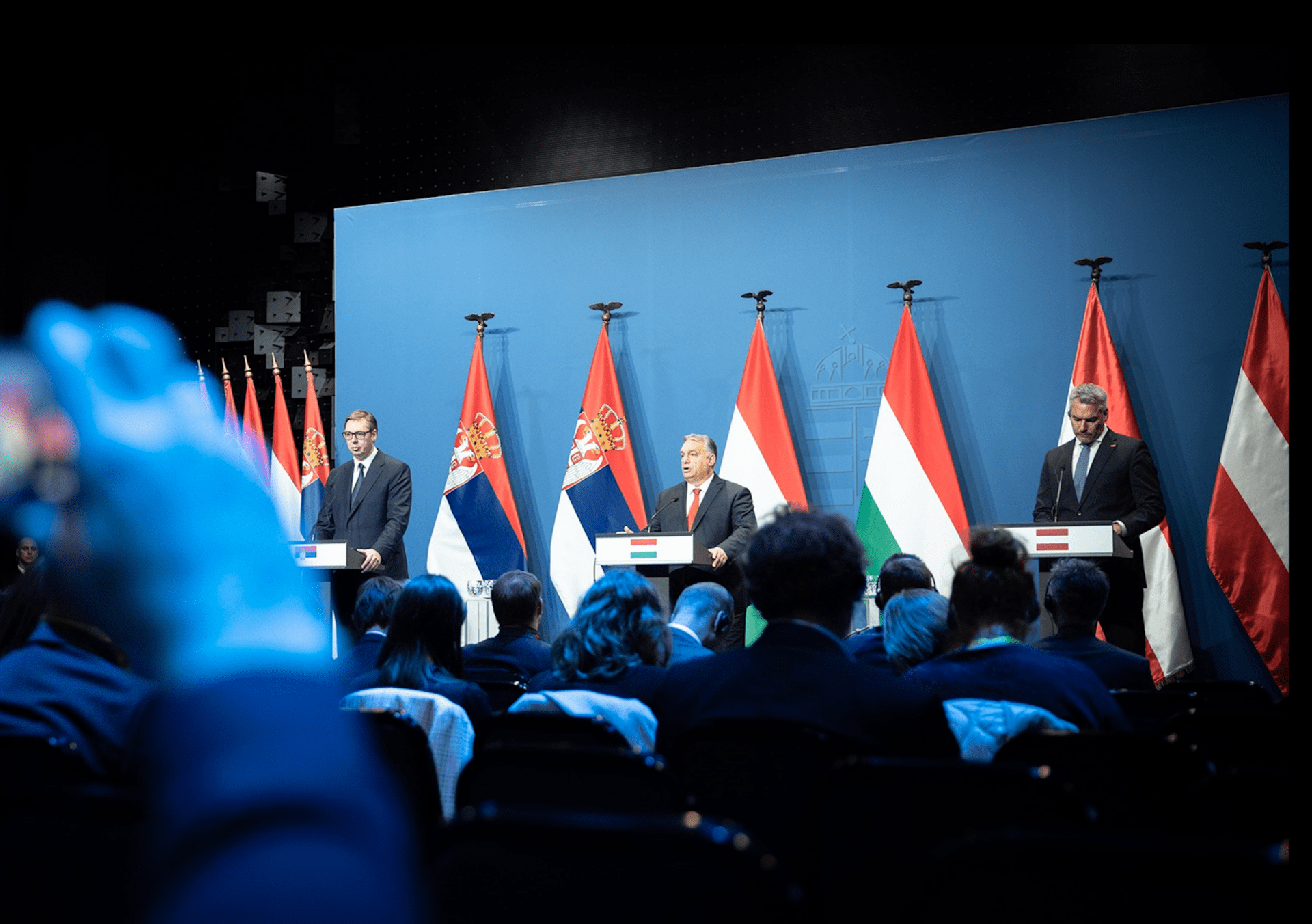

The first steps of this new strategy were revealed at the summit

All of this activity is a mere presage of what is yet to come over the next months and years as the crises progress, and therefore now it is time that the Schengen borders were reinforced. Hungary has already set up a new professional border patrol force, but Budapest also realised that it is not enough to stop the influx of illegal migrants at the gates; the whole phenomenon of migration needs to be addressed at an intergovernmental level. The first steps of this new strategy were revealed at the summit between the leaders of Austria, Hungary and Serbia earlier this week.

Politically speaking, Hungary has been widely known as perhaps the most anti-immigration country within the European Union ever since it took centre role in opposing the relevant EU policy directives in 2015. Hungary was the first to build a border fence to combat illegal immigration, setting an example that is still being followed by a steadily increasing number of countries around the bloc. It was also thanks to Hungary and Poland’s joint pressure within the EU institutions that Brussels was unable to push through with its initial plan of mandating Willkommenskultur for all member states. As outlined above, it became clear that in 2022, even though the war in Ukraine and the resulting energy crisis have overshadowed all other issues in the media, the migratory pressure on Schengen’s southern border not only persists but is relentlessly growing. Hungary once again assumed leadership in searching for solutions by hosting the Hungary-Austria-Serbia Summit with the goal of devising a joint action plan to be implemented on both sides of the EU’s current border.

‘Our southern border is constantly under siege’

Along with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the summit was attended by Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer from Vienna and Serbian President Alexander Vučić. At the press conference held after the meeting, PM Orbán explained that these three leaders represent the countries that are most direly affected by the growing migration crisis, and who spend the most energy, human resources and capital in order to stop it. Even in previous years, Austria and Hungary have been allocating sizable funds to help Serbia and North Macedonia—the countries closest to the European Union’s external borders on the West Balkans migrant route—but their cooperation would need to be expanded to face the mounting challenges. ‘Our southern border is constantly under siege’, Orbán said, and pointed out that the number of migrants attempting to illegally enter the EU will only increase in the following period. That is why Nehammer, Vučić and himself decided to come up with a new strategy that would make the fight more effective.

At the summit, the leaders agreed on a three-step draft plan, the legal and institutional details of which are yet to be specified in later meetings. First, the enormous pressure on the Serb-Hungarian (Schengen’s) border needs to be reduced by reinforcing the Macedonian-Serbian border as well, to slow down the waves of migrants before they enter Serbia. Second, these countries will have to find a way to deport the migrants residing illegally in their territories, preferably with the help of specific EU funds. And thirdly, they need to establish so-called migrant hotspots outside EU (as well as Serbian) territory where asylum requests would be processed. This latter proposal is very similar to how Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s new prime minister plans to deal with the migration issue: by setting up migrant hotspots in the form of offshore asylum centres.

The summit, albeit successful, was only the first step. This initial meeting of premiers will be followed by a second meeting in Belgrade between the respective ministers to agree on the specifics (such as funding, resources, manpower and legal framework), and a third meeting is also in the works to be held later in Vienna. This cooperation between Budapest, Belgrade and Vienna could open a new chapter in the European fight against illegal migration, and depending on the initial results, it may even be joined by other countries later on. Stopping illegal migration is— and should always be— regarded as a common European cause, even if Brussels doesn’t seem to care for the moment. Nevertheless, the first steps toward a systematic, unified approach have been already made in Budapest.