Introduction

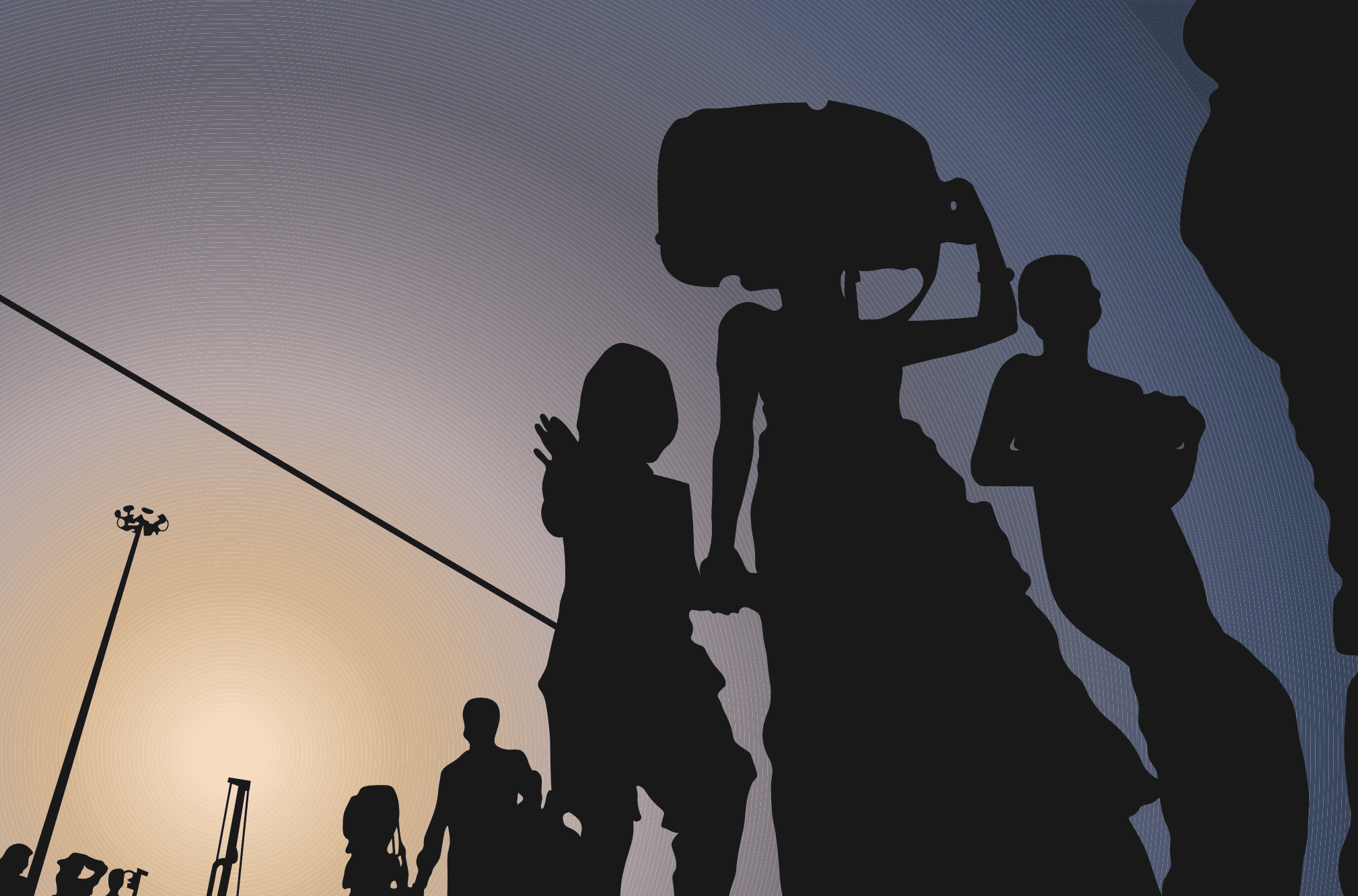

Without a doubt, illegal migration presents us with one of the greatest challenges of the twenty-first century. Therefore, the responsibility of the countries involved clearly goes beyond the short-term technical management of these processes. The migration policies in force today will affect essential social and political structures further down the line, while also demarcating the direction in which the culture will be headed. The purpose of this study is to explore the characteristic features of illegal migration to the European Union over the past five years, along with the major routes of migration, the political and economic situation of the source countries, and the global phenomena shaping migration.

For any serious survey of the migration crisis it is inevitably necessary to adopt a precise definition of basic terms—migrant, refugee, economic migrant, human trafficker— especially because these terms have often been used in a wrong or misleading sense in recent years, depending on the given political agenda. The diverse subjective interpretations of these notions are largely to blame for the current fragmented state of the EU’s system of refugee affairs, burdened by rifts that reflect a divergence in fundamental values. In thefirst section, I will review the aforementioned terms, along with the major paths and trends of migration to the EU. In the second, I propose to examine the changes in the EU’s migration policy. Finally, I will attempt to provide a detailed description of illegal migration to Hungary in the context outlined in the previous sections.

I. Basic Terminology of Illegal Migration and Major Migration Routes in the EU

The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, adopted in Geneva, defines the notion of ‘refugee’ for purposes of international law, sets forth the rights of refugees, and establishes the legal obligations of states vis-à-vis those refugees. The refugee is defined as a person who, ‘owing to well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country’. By contrast, a migrant is a person who leaves his or her home country, typically due to financial considerations, in order to settle or stay for a longer period in a different country.

Illegal migration is closely linked to human trafficking and organized crime. Under Hungarian criminal law, persons engaged in human trafficking are sanctioned by imprisonment. A human trafficker is defined as someone who assists another person or persons in crossing Hungary’s national border in violation of applicable regulations. The offense is qualified as aggravated when it involves a motivation of financial gain, multiple individuals as clients, the damaging or destruction of national border defence facilities, the extortion or torture of the persons being smuggled, and/ or is committed by an armed individual as part of a business enterprise or an organized crime ring. We can talk about organized crime when the criminal act is performed or agreed upon by several individuals in an organized manner.

In terms of their destinations, the major routes of migration to Europe fall into three large groups: the Central Mediterranean route, from North Africa to Italy, involving the crossing of the Mediterranean Sea; the Eastern Mediterranean route, to Western Europe via Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans; the Western Mediterranean route, to Spain, including the Spanish enclave of Ceuta and Melilla in North Africa, and the Canary Islands reached from the shores of West Africa. The latter path is often lumped together with the West African route because both are bound for the same destination. In 2021, a new route of illegal migration began to take shape along the Belarusian–Polish border as a result of a decision by the Belarusian political elite to transport masses of illegal migrants arriving from the Near East and Africa to the border of the EU. The Belarusian government decided on this course of action in response to a series of demonstrations and the movement to overthrow the ruling regime in the wake of the 2021 elections in Minsk.

Another distinction to be made is between source countries and transit countries. The former means the countries where migration stems from, while the latter typically consist of countries along the major routes of migration. Of course, a source country can be a transit country at one and the same time. For the Central Mediterranean route, the most important source countries are found in the Sahel Belt, comprising Mauritania, Mali, Burkina-Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, and Eritrea. What these countries have in common is overpopulation, exacerbated by the effects of climate change that have hit this zone particularly hard. It is characterized by short-term, regional migration. In the past four years, however, the increasingly powerful terrorist organizations (Islamic State, Boko Haram) have forced a significant part of the civilian population there to relinquish their former ways of life for good, launching increasingly formidable masses toward the transit countries of North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya). Those arriving here do not file for political asylum but move on instead directly toward Europe as economic migrants using the services of well-formed trafficking rings.

Owing to the direct support of the EU, the number of migrants returning to their home country voluntarily has skyrocketed from 2,777 in 2016 to 50,000 between 2017 and 2020

Of particular note among the transit countries of North Africa is Libya, where the EU, the African Union, and the UN created a joint working group on migration in 2017 with the aim of stepping up efforts to respond to the migration challenge on a shared platform. As part of the covenant, since 2016 the EU has sponsored the training of 477 new officers of the Libyan Coast Guard. The success of the programme is evidenced by the performance of the Libyan Coast Guard, which has rescued 50,500 migrants from the sea since 2017. Owing to the direct support of the EU, the number of migrants returning to their home country voluntarily has skyrocketed from 2,777 in 2016 to 50,000 between 2017 and 2020. However, the domestic political situation in Libya has been destabilized by civil war since 2014, and the escalation of the internal conflict in 2020 triggered an intense wave of mass migration from the country toward Europe.

Another phenomenon impacting illegal mass migration is the wave of democratization in North Africa that took off in 2012,1 resulting in the overthrow of various dictatorships that had put the brakes on illegal migration. In the attendant vacuum of power, human trafficking emerged as a new element, posing a serious security threat to Europe.

Despite the joint action of the EU and the UN, the number of sea crossings along the Central Mediterranean route increased dramatically between 2016 and 2018. Although the border locks forced by the coronavirus pandemic caused a significant drop in the number of border crossings, that number along this route increased by 154 per cent in 2020 once the restrictions had been lifted. The rise was in part due to the civil war in Libya, which amplified the role of Tunisia as another transit country geographically close to Italy.

The Eastern Mediterranean route constitutes the most important overland passage for illegal migration to Europe. Turkey has doubled as both a transit country and a target country, providing a home for the highest number of refugees in the world as a proportion of the native population (over 4.5 per cent). Currently more than 3.5 million

Syrians live in Turkey, most of them in the seven refugee camps set up to accommodate them.

In the aftermath of the migration crisis of 2015, the EU reached an agreement with Turkey in 2016, under which illegal migrants arriving at the Aegean Islands in Greece must be sent back to Turkey if they fail to file for asylum or their application is rejected. As part of the deal, the EU approved support funds totalling 6 billion euros for Turkey, of which the first 3 billion was disbursed by 2018. In return, Turkey undertook to enforce more stringent policies in monitoring the lines of illegal migration by sea and land, and to use the aid to provide for the welfare of refugees in the country.

The EU–Turkey pact meant temporary relief from the pressure of migration for Greece. For its part, the Greek government contributed to reducing that pressure in the long term by modernizing its border protection, building a wall and connecting technical barricades along the mainland border shared with Turkey. While illegal migration to Europe was thus gradually reduced thanks to the pact with Turkey, the secondary wave of the migrants stranded in Greece led to increased pressure on countries along the Balkan route, including Hungary.

In 2018, the EU reached an agreement with Turkey on the use of the remaining 3 billion euros in funds. The first instalment had been exhausted by Turkey by 2021, while the second instalment is earmarked for programmes running until 2025. The objective remains unchanged: improving the welfare of refugees in Turkey. Between 2016 and 2018, Ankara increasingly prioritized the voluntary repatriation of Syrian refugees, creating an artificial security zone along the Turkish–Syrian border to this end. By doing so, the Turkish government essentially sought to ease social tension over the refugee situation, brought about mainly by the still ongoing Syrian Civil War and the economic recession.

The migration trend along the Eastern Mediterranean route, having slowly risen from 2016 to 2018, reached a turning point in 2019, owing to the coronavirus pandemic and the border closures necessitated by it. The increasingly rigorous border protection regime introduced by Greece caused an unprecedented boom in human trafficking in the region, for the most part targeting the Aegean Islands and sections of the Turkish–Greek border not yet fortified with physical barriers.

In 2020, governments around the world implemented border closures in an attempt to keep the coronavirus at bay. In the short term, these measures helped stem illegal migration as well, even as they boosted internal political pressure within the host countries, including Turkey. Beset by massive economic difficulties, the Turkish administration tried to overcome the crisis in early 2020 by opening its borders to attain a better position at the bargaining table with the EU. Essentially, this amounted to using migration as a negotiating tool. Athens, however, succeeded in offsetting Turkey’s ambitions by strengthening its ties with international allies, and by modernizing its army so as to counterbalance Turkey’s power interests. The political tension between the two countries has continued to define migration trends along the Eastern Mediterranean route.

Although more Afghans have filed for asylum in the EU since the Taliban takeover, we cannot talk about a massive new wave of refugees at this point

This latter route has also been influenced by the withdrawal of American and NATO troops from Afghanistan in 2021. By any reckoning, the uncertainties in the wake of the Taliban takeover can be expected to set in motion further waves of illegal migrants. Preliminary studies carried out by the Greek authorities suggest that about one million Afghan citizens may soon set out toward the EU. Should the Taliban renege on the commitments they undertook upon assuming power, a significant portion of the Afghan population may decide to leave the country, exposing Turkey to another wave of refugees. This in turn would undoubtedly raise the issue of renegotiating the 2016 agreement between Turkey and the EU. Although more Afghans have filed for asylum in the EU since the Taliban takeover, we cannot talk about a massive new wave of refugees at this point. Among the factors impacting migration from Afghanistan, the most significant are the country’s economic situation and the relations between the Taliban elite and the international community.

The Western Mediterranean route, which targets Spain via Morocco and Algeria, saw a steady and intense increase in traffic between 2016 and 2018, in part due to the policies introduced by Italian Minister of the Interior Matteo Salvini, which demonstrated Italy’s capacity to shut down its marine borders. By 2018, the Spanish direction had become the number one route of illegal migrants bound for the EU, the majority of whom came from sub-Saharan countries. The dynamism of the growth is evident from the figures. The number of illegal migrants arriving in Europe through this route rose from 8,000 in 2016 to 22,000 in 2017 and 58,000 in 2018—a seven-fold increase over the period.

Following a peak in 2018, the following year saw a decline in new arrivals as a consequence of the bilateral agreement signed in February 2019 between Morocco and Spain on maritime rescue operations. Morocco then shut down its borders because of the pandemic, further relieving the pressure of migration. In 2019, Frontex began to take an active part in enforcing Spain’s external borders, which proved instrumental in curbing human trafficking operations.

By 2021–2022, Portugal had emerged as another major target country of the Western Mediterranean route for migrants deterred by the efficacy of Spain’s measures in protecting its own borders.

Ceuta and Melilla, the two Spanish enclaves in North Africa, faced extraordinary pressure in 2021, when tens of thousands of migrants arrived there from Morocco in a matter of a few weeks. The crisis was triggered by the political friction between Morocco and Spain. The latter country responded by stepping up the border protection of the two enclaves, successfully reducing the number of new arrivals to 3,000 people in 2021, according to UN data.

Mention must be made here of the Western African route, which is also used by migrants headed for Spain. Most of them arrive at their destination in the Canary Islands from sub-Sahara through Morocco, Western Sahara, Mauritania, Senegal, and Gambia. The number of illegal new arrivals along this route hovered around one to two thousand in 2020, but has increased dramatically since then. Much of this change can be attributed to the coronavirus pandemic, which forced the majority of African countries to shut down their borders, further aggravating the position of the already underdeveloped West African region. Under the circumstances, those seeking to reach the Canary Islands by these means must be regarded as economic migrants.

The newly formed migration route across the Belarusian border to Poland and Lithuania is linked with the 2020 presidential elections in Belarus, which set off a chain of demonstrations across the country for the removal of the regime in power. The Belarusian government responded with violent repression, for which it was condemned by the EU and the international community at large. The Belarusian government’s response is the most eloquent example of how to use migration as a tool in one’s political arsenal. Both Lithuania and later Poland took action to halt the flow of migrants by building a border fence and reinforcing their border-defence personnel.

II. Changes in the EU’s Migration Policy

In light of the migration crisis unfolding in 2015 and the experiences over the years since then, the EU’s current administration of refugeeaffairs can safely be called both flawed and obsolete. In order to grasp the fragmented nature of the system it is necessary to define thethree basic types of migrants and migration. The first group comprises legal migrants enjoying freedom of movement within the SchengenArea. The second consists of migrants arriving from outside the EU in possession of valid documents. The third is made up of those crossing the EU’s borders for financial reasons without proper legal authorization. These are illegal migrants.

Pursuant to the Dublin Treaty, the handling of illegal migrants is the responsibility of the receiving country. The refugee crisis of 2015 made it clear that this system is outdated, if only because the integration or deportation of illegal migrants presents the frontline countries of the Mediterranean with insurmountable difficulties. As a consequence, the mandatory admission of migrants on a quota basis became a divisive issue within the EU.

While Hungary has consistently rejected the mandatory distribution of incoming migrants in a quota system ever since the refugee crisis erupted in 2015, the project has been actively advocated by certain Western European states. Hungary’s recommendation was to create hot spots outside the territory of the EU, based on the idea that it would not be necessary for someone to enter the EU in order to file for refugee status. This would pre-empt the problem of subsequent deportation—a process not only costly but often impossible to implement in the real world. Today, more and more member states have come round to the Hungarian position in this matter and begun to support the alternative of creating hotspots and strengthening the physical protection of borders. The viability of this solution has been amply demonstrated by the EU’s willingness to financially support the maintenance and operation of existing border fences.

The five frontline countries directly facing migration along the major routes, known as the MED5,2 have adopted bilateral agreements in an attempt to mitigate the pressure on their countries. Such support deals were signed by the EU with Turkey and, subsequently, with Libya and Morocco. Although these pacts have yielded a meaningful decline in illegal migration, they open opportunities for exerting political pressure using migration as a weapon. Indeed, this potential leverage was exploited by Turkey in the spring of 2020 and by Morocco in respect of the Spanish enclaves.

At present, there are three prevailing views on migration in the EU. Those seeking to encourage legal migration consider it desirable and vital as a way of offsetting the decline in workforce and population growth caused by the coronavirus pandemic, adding humanitarian considerations to their arguments based on the economic potential inherent in migration. The states rejecting migration contend that the integration of migrants is an enterprise doomed to failure from the start, given the broad cultural differences and a lack of willingness to fit in with the host country. The fiasco of trying to integrate migrant groups admitted to date certainly underlines the illusory nature of the idea. In this second view, the potential threats entailed by illegal mass migration, including infiltration by terrorists, health hazards, and the formation of parallel societies, call for the protection of borders and sovereignty as the obvious solution. The dispute between these first two camps is intensified by the blurring of semantic boundaries between the categories of illegal migrants, economic migrants, and refugees. The third approach is held by the frontline countries, with their essential vested interest in obtaining and increasing their share of the support funds they can draw from the

EU in return for handling the migration crisis. The single question on which the EU has arrived at a widespread consensus in recent years has been the operation of Frontex, an organization whose budget has quadrupled since 2015. Despite accusations of abuse, the agency has succeeded in renewing its mandate to protect the external borders of the EU. Another option for the EU’s migration policy was presented by the Migration Pact, which Hungary refused to join and which remained in effect until 2020. The pact urged mandatory solidarity and cooperation in a wide range of issues including migration, border protection, vetting, refugee policy, integration, repatriation, and partnership with entities outside the EU. It would have enabled each member state to contribute to the Union’s efforts to deal with migration only so far as it saw fit to do so.

At the same time, the objectives articulated in the pact returned—repeatedly, if in a different guise each time—to the idea of distributing migrants according to a quota system. It was in an attempt to resolve this dilemma that Hungary proposed the creation of external hotspots, as previously mentioned.

The EU’s migration policy in recent years has shifted the focus from supporting external third countries to bolstering the Schengen borders and revamping its obsolete refugee management schemes. A number of member states have abandoned their former stance and begun to side with Hungary’s position, agreeing that the halting of illegal migration cannot be divorced from issues of national sovereignty and the protection of European culture. The shift in attitudes has been attested to by several bilateral agreements3 and projects of operative collaboration in border protection with non-EU countries.

III. Trends of Illegal Migration to Hungary

The entire bill was footed by the Hungarian state, despite the fact that the fence protected an external border of the EU, stretching along the length of Hungary’s borders with Serbia and Croatia

After the record year of 2015, starting in early 2016, the number of successful crossing attempts was reduced significantly, owing to Hungary’s border protection measures. Recognizing the gravity of the situation, the Hungarian government set about fortifying its physical barriers without delay. Essentially, this meant building a tiered barrier system consisting of two rows of fencing with barbed wire, complemented by a multi-component surveillance system. The entire bill was footed by the Hungarian state, despite the fact that the fence protected an external border of the EU, stretching along the length of Hungary’s borders with Serbia and Croatia. Hungary was condemned by the majority of member states on the grounds that humanitarian concerns should have taken precedence. The rapidly increasing pressure of migration also necessitated the enactment of new legal institutions. Formerly sanctioned as a misdemeanour, the act of unauthorized border crossing was reclassified by the National Assembly as a felony, accompanied by the new criminal categories of illegal transgression and vandalization of the physical barrier. It is important to see, however, that these physical and legal barriers have continued to serve the territorial integrity of the Schengen borders to this day.

Ever since 2016, the country’s southern border has been subject to a steadily increasing number of illegal crossing attempts, while human traffickers in the region have staked out new routes heading toward Slovenia and Croatia. It is safe to say that the border barrieris the embodiment of Hungary’s migration policy.

The pressure of migration on Hungary’s borders has been growing since 2016, despite the fact that the saturation of the Eastern Mediterranean route has been rather uneven. This is explained by the secondary wave of migrants stranded in Greece.

The figures posted by Hungary were naturally not immune to the effect of border closures implemented globally in early 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. In fact, trends of decline observed around the world failed to bring relief to Hungary’s borders. The threat to public health linked to waves of migration has emerged as a new risk factor. The overwhelming majority of migrants arriving at the borders have still not been vaccinated for COVID-19.

The Hungarian government holds that no alien should be able to enter a foreign country except in compliance with international regulations, in possession of the requisite documents, and at designated points of border crossing. It follows that a person seeking asylum does need to enter the country in order to file for refugee status. For them, so-called transit zones have been created along the country’s southern border, in an attempt to prevent the cumbersome process of deporting those whose applications have been rejected. In a judgement of 2020, after the European Court ruled that Hungary had defaulted on its legal obligations as a member of the EU, the transit zones were abolished before the end of that year. At present, petitions for asylum in Hungary can be submitted in any of the country’s embassies. The possibility of a rejection obviates the need to set out on a journey, typically through several safe countries.

The success of Hungary’s border fence is reflected by the fact that several other member states of the EU have implemented similar protection measures since 2015. A case in point is Greece, which is now in the process of fortifying its mainland border with Turkey with a five-metre tall steel fence and surveillance systems to match. In order to improve the efficiency of uncovering and preventing illegal migration, the Hungarian law-enforcement authorities have contributed to the protection of relevant borders based on bilateral agreements of cooperation. Hungarian police detachments are currently assigned to the borders with North Macedonia, Croatia, and Serbia.

Hungary’s government is of the position that the best solution is not to import the problems of illegal migration but to handle the problems creating migration waves locally. In 2017, it launched a programme named Hungary Helps, providing aid and assistance for individuals and groups suffering ethnic or religious persecution in developing countries. Beyond first-response humanitarian help, the programme envisions cooperation on development projects, predominantly with countries in the Near East and sub-Saharan Africa. By implementing such programmes, Hungary is contributing to eradicating the root causes of illegal migration from some of the leading source countries.

Forecast

Considering current trends of illegal migration to the EU, it is reasonable to expect a further swelling of the flood in the coming years. In the short term, it is unlikely that the source countries will be able to stabilize their internal, security, and economic situation, which is an inevitable precondition for keeping their populations at home. The building of fences and the tightening of border protections may lead to new, alternative routes of migration, while the overall number of attempts to cross the EU’s borders can be expected to remain constant.

For the past six years, the migration policy of the EU has diverged considerably from that followed by individual member states. The documents drafted to ensure joint action have failed to offer a solution to the problem of illegal migration that would guarantee the national sovereignty and national security of individual member states in the long term. Moreover, the growing pressures of migration cannot be expected to help reduce the gap between the differing positions. In flagrant disregard of worsening figures and a flourishing human trafficking business, the pro-migration lobby remains strong both within the establishment of the EU and within the member states themselves.

Ever since the outbreak of the migration crisis, Hungary has stood by its migration policy tailored to the needs of Hungarian society, and has consistently opposed mandatory quotas and solidarity. The government’s measures of strengthening border protection, forging operative cooperation with third countries, and aiding source countries in their efforts to deal with their problems locally, serve the interests of halting illegal migration instead of simply managing and orchestrating it. Hungary’s position has been vindicated by a string of walls being built along the Schengen border and by the mounting discontent with illegal migration within the EU. Although the political opposition in Hungary has put forward a few vague proposals, the national administration will respect the will of the decisive majority of Hungarian citizens as it continues to defend the borders of the country and the EU, its own security, and European culture.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel

NOTES

1 Known as the Arab Spring.

2 The ‘Mediterranean 5’, namely the frontline countries of Greece, Italy, Spain, Malta, and Cyprus. 3 Agreements of cooperation in combatting illegal migration were signed between Spain and Morocco in early 2019, and between Portugal and Morocco in 2022.