This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 2 of the print edition.

Nowadays, the hazards of prices escalating beyond any reasonable limit are compounded by the fact that the phenomenon is not confined to consumer prices but has encompassed wholesale, invested assets, as well as incomes and wages. Moreover, the rapid, global spread of uncertainty, aggravated by wartime circumstances, constitutes a further obstacle in the path of efforts to regain control over inflation as successfully as we managed after the 1980s, with the exception of a few developing countries. This lends special gravity to the current inflation challenge, which demands that we find a way to accommodate the near and more distant future of prices in the decisions we make today.

In this study, I seek to answer that question by exploring the main underlying causes and correlations of inflation. For starters, it is worth pointing out that inflation is highest in the countries of the Baltic and Eastern Europe due to the rising prices of energy and food products, even as the price hike of energy and fuels is more modest in Eastern Europe than elsewhere. Inflation in industrial products is a general tendency across the member states of the European Union, but wages have been rising more consistently in those European countries where the revenues of the service sector have been increasing faster.

Let us take a look at food prices first. Hungary has led the four Visegrád countries in terms of the rate of rise in food prices since 2006, in part as a result of weaker exchange rates. Another reason for this has to do with the low participation of subsidized farmlands, particularly in the context of recurring droughts afflicting agricultural production. Even though Hungary continues to lead the region in terms of output, the ratio of irrigated lands lags far behind that in the Mediterranean countries and the Netherlands.

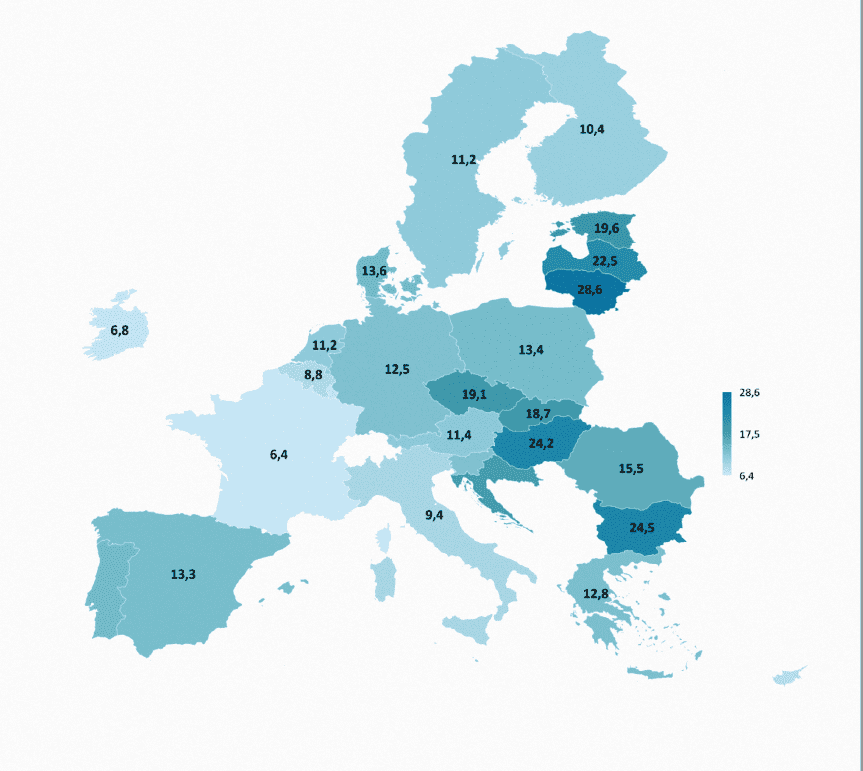

The high food prices in Hungary are also due to the 27 per cent VAT assessed on food products, the highest in the EU, where the average is 20.4 per cent. Finally, it is important to note that food products weigh more in total household consumption in Eastern Europe, with Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Hungary posting 24–26 per cent, compared to the EU average of only 17.5 per cent. This is another factor contributing to inflation. The overall trend in European food prices is shown in Figure 1 below.

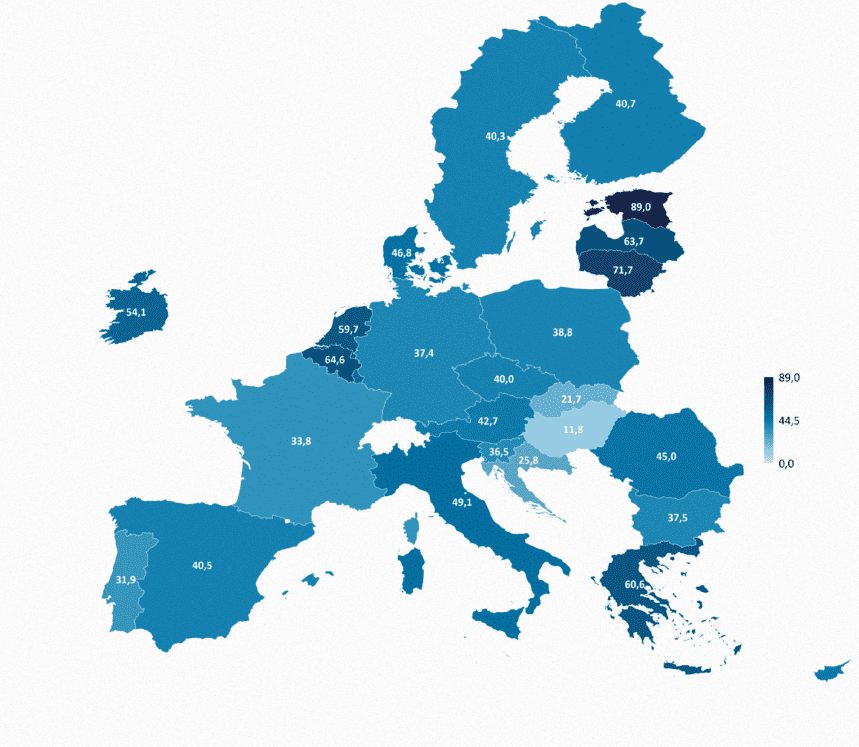

The other major factor impacting overall inflation consists of higher energy and fuel prices. That we have entered what looks like the harshest energy inflation for decades is indicated by the fact that, in November 2021, crude prices surpassed the average of 2017–2019 by 30 per cent, while the price of both electricity and gas skyrocketed by 350 per cent compared to the same reference period. This is particularly true for gas, an important energy source (27 per cent primary increase and a 73 per cent hike for end users, both residential and corporate). In the utility expenses of companies, electricity accounts for a multiple of their gas bills, and fuel costs also figure very highly in the equation. Therefore, it matters a great deal how global price increases affect corporate bills, which in turn ratchets up inflation further while scaling back household purchasing power. Fortunately, in Hungary, centrally regulated utility prices have helped to keep households more or less immune to escalating utility costs. It is also worth pointing out that higher energy prices have an adverse effect on a nation’s fiscal balance, for instance, due to the losses incurred by state-owned corporations and the higher energy costs shouldered by the municipalities. As a result of all these processes and interactions, the inflation in energy and fuel prices in Hungary is the lowest in the EU. In this ranking, as of June 2022, Hungary (11.8 per cent) was followed by Slovakia (21.7 per cent), Croatia (25.8 per cent), Portugal (31. per cent), Slovenia (37 per cent), Bulgaria (37.5 per cent), Poland (38.8 per cent), and the Czech Republic (40 per cent). The situation of the other EU member states is shown in Fig. 2 below.

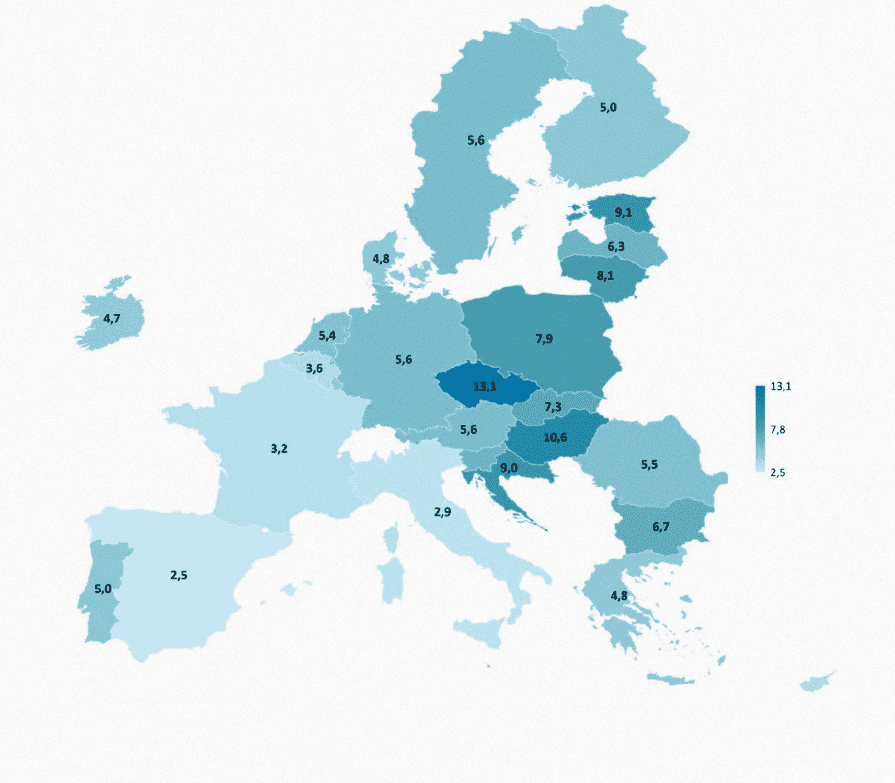

A price hike in industrial products is also prevalent across the EU, with extremities posted in June 2022 by the Czech Republic (13.1 per cent) and Spain (2.5 per cent). The second highest was Hungary, with 10.6 per cent, of which approximately 3 per cent must be ascribed to the weakening national currency. Worsening exchange rates also contributed to higher inflation in Sweden and Poland. Fig. 3, showing the regional trend in the inflation of industrial product prices, tells us that this index was higher than 6 per cent in all countries of East Central Europe and the Baltic, with the exception of Romania. This is in contrast with the northern and Mediterranean countries, where the rate was more modest, with Spain reporting the lowest figure (2.5 per cent), followed by Italy (2.9 per cent) and France (3.2 per cent).

The escalation of industrial product prices has been simultaneously stimulated by:

- supply factors (passed-on increases in the prices of raw materials, anomalies in international supply chains, such as the so-called container crisis, droughts impacting food supplies, the effects of climate change, the introduction of more stringent environmental regulations);

- factors on the side of demand (increased consumer demand in excess of ‘business as usual’ capacities, excess consumption at the expense of household budgets, and the reflection thereof in prevailing prices of market services).

It is characteristic of the current global inflation cycle that each of these factors and influences has asserted itself in it. As a further challenge, these effects can not only infiltrate but positively come to form an integral part of our expectations regarding subsequent inflation, the prevention and alleviation of which present fiscal and monetary policies with an urgent task if we are to stabilize and maintain viable price levels.

One crucial aspect in this regard is that the changes in the real economy and inflation caused by the coronavirus pandemic came about due to a combination of factors on the side of both supply and demand. On the side of supply, prices went up as a result of more expensive raw materials and energy, compounded by interruptions in supply chains. The process was aided by demand factors such as the need of households to make up for consumption deferred during the crisis and a boost in demand owing to subsidies from the national budget. The central banks responded by attempting to prevent a concurrent financial crisis by making more monetary funds available on demand, even though this, combined with the fits and starts in the production sector, eventually contributed to escalating prices across the board.

‘80 per cent of the rise in inflation in Hungary could be attributed to external circumstances, and only 20 per cent to strictly domestic reasons’

In terms of the inflation of industrial product prices, it is important to see that the price hikes in several countries have been greater than those of the inflation in the service sectors. This amounted to a shift in the structure of overall inflation, forced by the cost constraints underlying the inflation of industrial product prices and the altered structure of consumption due to the pandemic. This shift, compared to the average for the period between 2010 and 2019, was largest in eleven member states, including Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Finland, and Hungary. By contrast, in countries where the inflation of prices of market services is higher than that of industrial products, wages tend to rise more dynamically as well. This trend is readily observed in the Baltic states and in East Central Europe, including Hungary. Indeed, in these regions, further intense dynamic shifts in wages can be expected, especially in the service sector, even as the processing industries will likely be posting a more modest increase in wages. The foregoing analysis of inflation factors encourages me to cite and concur with the preeminent economist Professor Emerita Katalin Botos in making a parenthetical remark concerning the efforts of member states in the Baltic and East Central Europe to close the European wage gap.

‘The belated, retroactive corrections of wages in the sectors of education, health, and culture—slow and incomplete as they may be— have been accompanied by escalating social tension’

To the aforementioned causes of inflation and the major psychosis triggered by the ongoing war, we must certainly add the demands for higher wages that have been voiced by the workforce of Eastern European countries for a historically meaningful period. To quote Botos, I am referring to the time when ‘the earnings of citizens were tampered with on ideological grounds; when the members of the intelligentsia, and specifically educators, were judged to be of lower rank than manual labourers and workers. The dire consequences of this communist experiment have never been remedied by anyone. Not that we have ever had the resources to do it. Any surplus revenues that could have occasioned such a wage adjustment have for decades been spent on servicing the national debt. In the past, even the EU never permitted its funds to be used for the improvement of wages.’1 Of course, the idea of settling the question on a market-oriented basis comes up, except that ‘in Eastern Europe, these considerations have never been a part of establishing wages’.2 There were other initiatives, such as the very vocal proposal after the democratic turn for a new Marshall Plan, which could have allowed us to shake off the shackles of an ingrained economic structure inherited from our past as a country under communist rule.3

‘The rapid, global spread of uncertainty, aggravated by wartime circumstances, constitutes a further obstacle in the path of efforts to regain control over inflation’

The belated, retroactive corrections of wages in the sectors of education, health, and culture—slow and incomplete as they may be—have been accompanied by escalating social tension and an even higher rate of inflation inevitably caused by it. This clearly distorts our ability to make meaningful statistical comparisons in the international context.

Last but not least, let me stress that, in the complex system of correlations which attend the phenomenon of inflation in Europe, the role of international factors and influences cannot be overestimated. In closing, therefore, it is important to remember that, compared to the stable period of 2017–2018, some 80 per cent of the rise in inflation in Hungary could be attributed to external circumstances, and only 20 per cent to strictly domestic reasons. Taking into account the ambivalent effects of the war situation and the ensuing sanctions, these rates are likely to remain important determinants of inflation developments in 2023.

NOTES:

1 Katalin Botos, ‘Infláció, összegzés’ (Inflation: A Synopsis) (Manuscript, 2022).

2 Botos, ‘Infláció, összegzés’.

3 Gusztáv Báger and Miklós Szabó-Pelsőczi, eds, Global Monetary and Economic Convergence. On the Occasion of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Marshall Plan (Ashgate, Aldershot, Brookfield, USA, Hong Kong, Singapore, Sydney, 1998), 513.

Related articles: