Even though Christianity is perhaps the most persecuted religion in the world and the severity of the living conditions of oppressed Christians is getting worse year by year, the topic hardly ever gets substantive coverage in the global news media. For those of us well-acquainted with the facts regarding the plight of Christians living in countries where they are discriminated against, it is hard to comprehend why this burning issue gets so little attention in the press. However, it is not just the mainstream media that fails to focus on this topic as much as it would merit, but the academic world as well. Realizing the lack of serious studies in this field, a group of researchers, including myself, at the Hungarian think-thank called the Danube Institute has launched a research program this year titled “Attacks on Christian Communities and Institutions”. Our team, led by programme director Prof. Jeffrey Kaplan, will conduct fieldwork in ten countries in the Middle East, Africa and in Europe, where, although in different forms, discrimination against Christians is perceptibly on the rise. The project will investigate three categories of anti-Christian violence: 1) Religious persecution, which is the product of active governmental policy; 2) Intercommunal violence conducted by sub-state actors targeting Christian communities and institutions; and 3) Internecine violence in which different factions of the same religious tradition are in conflict.

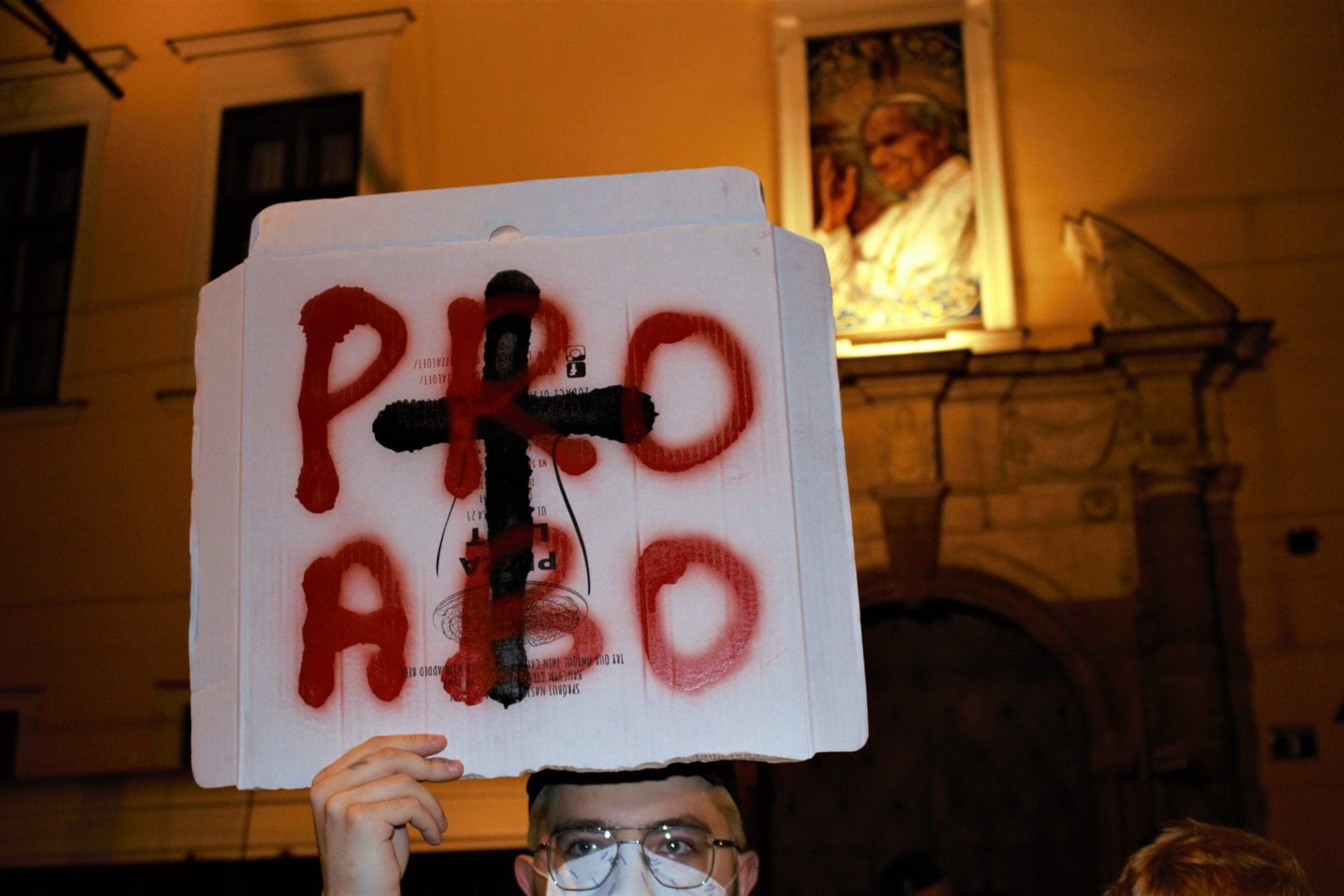

Over the past few years, Catholic churches and prelates in Poland have been subject to attacks by mainly feminist and LGBTQ activists who claim be Catholics themselves

At the end of April, we completed our first fieldwork trip to examine the unique situation in Poland, which has been included in our research as a case of internecine violence. Over the past few years, Catholic churches and prelates in Poland have been subject to attacks by mainly feminist and LGBTQ activists who claim be Catholics themselves. The first wave of such attacks started in 2020 with feminist groups protesting against the ruling of the Constitutional Tribunal that tightened abortion law in Poland. The second wave of attacks has been ongoing since 2021. These cases are concurrent with a new wave of attacks by LGBTQ groups protesting both against the abortion legislation and the street violence aimed at their community. In the course of our fieldwork trip, we conducted eleven interviews with people on all sides of the conflict: members of conservative Catholic organizations, pro-life NGOs, feminists, LGBTQ activists, and the so-called “Church Defenders”.

PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK

The question may arise: how is it possible that there are violations against Christians in a country where, according to statistical data, 87 per cent of the population is Roman-Catholic? [i]

The conflict that led to the attacks on Catholic churches had in fact started in 2016, when a draft bill to ban abortion was submitted to Parliament. In that year, the vocal opposition of the feminist groups was successful as the proposed bill was overwhelmingly voted down in the Polish legislature. [ii] At that time—as our interviewee from the conservative institute called Ordo Iuris said—the bill was only partially supported even by the Catholic Church. Four years later, however, in 2020, the Polish Parliament did pass a strict abortion law that only allows abortion if the woman’s life or health is at risk or if the pregnancy results from a criminal act. Feminist activists, outraged by the law, organized the National Women’s Strike in Warsaw, which started a wave of attacks on Catholic churches. According to a report by Polish think-tank Laboratory of Religious Freedom, in 2020 there were 280 cases of violations of the right to religious freedom throughout Poland.[iii] Attacks varied from verbal harassment to the vandalizing of churches, religious symbols and objects, and also included physical attacks on not just clergy and laity, but also on conservative government officials and pro-life activists.

Many young people joined the protests not necessarily because they opposed the abortion law, but because they were frustrated by COVID-19 restrictions and how the government handled the pandemic

Besides the controversial abortion law, there were several other drivers of the strike. The COVID-19 pandemic greatly affected the dynamic of the protests. Many young people joined the protests not necessarily because they opposed the abortion law, but because they were frustrated by COVID-19 restrictions and how the government handled the pandemic. Another reason why so many people attended the protests was that they felt it was a great opportunity to express their dissatisfaction with state and church not being fully separated in Poland. Moreover, the protests were also motivated by the powerful documentary about the sexual abuse of children within the Catholic church in Poland titled: Hide and Seek. [iv] The documentary that was released in 2020 was seen by 2.5 million people in less than 24 hours, and today, more than 8 million people have seen it only on YouTube.[v]

When we asked our interviewees about the lack of secularization in Poland, representatives of conservative think-tanks and NGOs were of the opinion that while it is true that the Catholic Church in Poland has more power than in other countries, the church does not interfere with politics as a rule. They usually added that the Catholic Church and its teachings have played an integral part in Polish history, and the reason why most Poles do not have a problem with the close relationship between the Church and the government is that almost 90 per cent of the Polish population is Catholic. The fact that Catholicism has a major influence in Poland is evidenced by the fact that even many of the feminist and LGBTQ activists who criticize the current leadership and take part in the protests identify as Catholic. However, data suggest that in recent years many young Poles have turned away from the Church. When we asked about this phenomenon, our respondents cited the increasing influence of liberal movements on the younger generations as an explanation, as well as the paedophilia scandals within the Catholic Church, which have alienated a large number of formerly church-going youth.

PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK

Another interesting aspect of the attacks was the role of the so-called “Church Defenders”. One of the most common ways in which activists protested against the Catholic Church was by disrupting Sunday masses. As the police were apparently unable or in some cases unwilling to protect the churches from these kinds of protests, members of far right nationalist movements organized a group known as “Church Defenders,” who took the matter of protecting churches into their own hands. According the spokespersons of the Defenders we spoke to, they always tried to proceed as safely and non-violently as possible. By contrast, some feminist activists we interviewed told us stories of some protesters whom the Defenders deemed to be too aggressive were beaten up. On the other hand, “Church Defenders” belonging to the All-Polish Youth movement noted that they had been greatly outnumbered and often physically attacked by the protesters.

According to the mainstream media, the influence of the LGBTQ movements and feminist activists has grown immensely in Poland in recent years. As opposed to that, members of one of the conservative Polish organizations told us in an interview that the opposition movement has actually lost much of its popularity and impetus since 2020. In their opinion, the reason why the protests no longer attract as many people as before is that after the 2020 riots, attacks on churches became even more radical; therefore, many Poles decided not to participate in these kinds of protests anymore because, as our interviewee added: ‘It’s important to understand that Polish people don’t like radicalization.’

[i] Eurydice, ‘Poland: Population: demographic situation, languages and religions,’ Ec.europa.eu, (8 January 2022), https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/population-demographic-situation-languages-and-religions-56_en, accessed 30 May 2022.

[ii] BBC News, ‘Poland abortion: Parliament rejects near-total ban’, BBC News, (6 Oct. 2016), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37573938, accessed 26 May 2022.

[iii] Laboratory of Religious Freedom, ‘Report on violations of the right to religious freedom in Poland in 2020’, Laboratorium Wolnosci Religijnej,(2020), https://laboratoriumwolnosci.pl/en/reports/ , accessed 26 May 2022.

[iv] Paulina Guzik, ‘New documentary highlights abuse cover-up in Poland’, Crux, (17 May 2020), https://cruxnow.com/church-in-europe/2020/05/new-documentary-highlights-abuse-cover-up-in-poland, accessed 30 May 2022.

[v] Zabawa w Chowanego, [online video], Sekielski, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T0ym5kPf3Vc&feature=emb_title, accessed 26 May 2022.