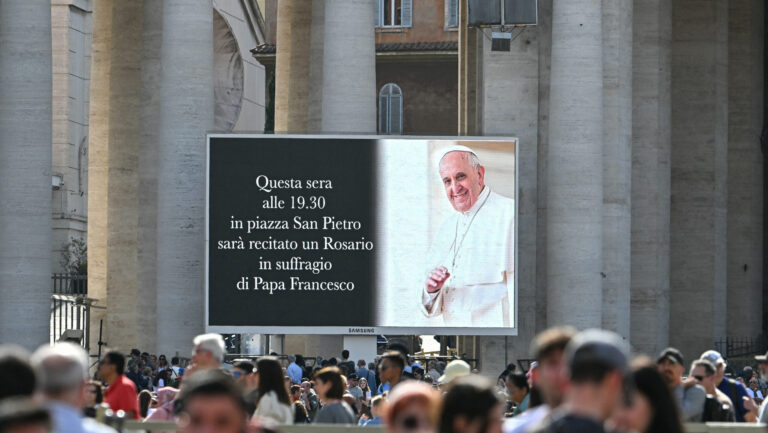

On the last day of 2022, the Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI passed away. An acute German theologian and orthodox enforcer of Church doctrine had shocked the world when he announced his resignation on 11 February 2013, living for nearly a decade afterwards behind Vatican walls.

Brief Biography

Upon his election to the Throne of St Peter on 19 April 2005, then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was one of only four cardinals still alive who had been raised to the Sacred College by Pope Paul VI.

After he completed his philosophical and theological studies in 1951, he was ordained to the priesthood that year. In 1953, he obtained his doctorate in theology with a thesis entitled ‘People and House of God in St Augustine’s Doctrine of the Church’. Four years later, he qualified for University teaching with a dissertation on ‘The Theology of History in St Bonaventure’. After teaching dogmatic and fundamental theology at the Higher School of Philosophy and Theology in Freising, he went on to teach at Bonn, from 1959 to1963; at Münster from 1963 to 1966; and at Tübingen from 1966 to 1969. During this last year, he held the Chair of dogmatics and history of dogma at the University of Regensburg, where he was also Vice-President of the University.

From 1962 to 1965, he made a notable contribution to Vatican II as an ‘expert’, being present at the Council as theological consultant to Cardinal Joseph Frings, Archbishop of Cologne. On 25 March 1977, Paul VI appointed him Archbishop of Munich and Freising; he was consecrated bishop on 28 May of the same year. Ratzinger was the first diocesan priest in eighty years to take on the pastoral governance of the great Bavarian Archdiocese.

There are two notable acts of his that stirred controversy: his Regensburg address in 2006 and his Motto Proprio Summorum Pontificum (On the Use of the Roman Liturgy Prior to the Reform of 1970) in 2007.

The Regensburg Address

In his famous discourse at Regensburg, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the very nature of man’s understanding of a free conscience, his thirst for knowledge in both reason and revelation, his understanding of the limitations of the will and the nature of his ability to understand his neighbour.

The Pontiff raised the question whether, under the notions of faith and reason, is it moral to convert a person against his or her will by means of violence? Referring to Muslims who blindly follow the lead of Islamic militants, he sought to explain the obstacles in finding a common ground between Christian-based Western society and Islam. Thereupon, Benedict, citing the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus (1391-1425), stated:

‘The emperor [Manuel II] must have known that sura 2, 256 reads: “There is no compulsion in religion.” According to some of the experts, this is probably one of the suras of the early period when Muhammed was still powerless and under threat. But naturally the emperor also knew the instructions, developed later and recorded in the Quran, concerning holy war. Without descending to details, such as the difference in treatment accorded to those who have the “Book” and the “infidels,” he addresses his interlocutor with a startling brusqueness, a brusqueness that we find unacceptable, on the central question about the relationship between religion and violence in general, saying: “Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.” The emperor, after having expressed himself so forcefully, goes on to explain in detail the reasons why spreading the faith through violence is something unreasonable. Violence is incompatible with the nature of God and the nature of the soul.’

Overshadowed by the violent reaction and rioting throughout the world, the Regensburg address sought to identify, as Robert Sokolowski, Professor of Philosophy at the Catholic University in Washington explained, ‘an issue that is at the core both of the cultural crisis in the West and the conflict between the West and militant Islam.’ In addition, as he constantly called to mind during his Pontificate, Pope Benedict XVI also strived to highlight the importance of resurrecting the concept of the natural law in society.

Summorum Pontificum

The Pontiff Emeritus, with his controversial Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, criticized by non-conformists, i.e., those who upheld a fundamental application of the Missal of Paul VI that introduced what would be known as the Novus Ordo mass, officially reintroduced the public celebration of the ‘Traditional Latin Mass’ (also known as the Tridentine Mass). The Tridentine Mass was codified by Pope St Pius V in 1571 after the conclusion of the Ecumenical Council of Trent (1545–1563), and was last promulgated by Pope John XXIII in 1962.

What the Pontiff essentially did was not just restore the external beauty of the sacred liturgy, calling to mind the liturgical abuses after the Second Vatican Council, but he reminded us that contrary to so-called experts, the Traditional Latin Mass was ‘never abrogated’—it is still in use and drawing more and more young Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

Regrettably, Benedict XVI’s legacy is marked by his resignation, with many wishing he had never abdicated the Papal Throne, myself included. Yet it is important, notwithstanding his misgivings, to recall, as with anyone else, the good he did during his brief reign as Pope.