Romanian political life has changed overnight. An independent candidate, Călin Georgescu, shocked the mainstream party elites and the media by securing 22 per cent of the votes in the first round of the presidential election. This is a development that remained wholly unpredicted by all significant polling companies and experts. As one out of fifteen candidates, he had conducted a persuasive online campaign, primarily on TikTok, focusing on the importance of an autochthon economy, the inherent superiority of rural life in Romania, and essentially claiming that just like a national poet from the 19th century, he is a divine messenger.

The campaign consisted of thousands of TikTok profiles distributing ten-second videos about him, with many influencers suggesting in the past weeks that they would vote for him. According to Georgescu, he didn’t spend any money on the campaign, but the scale and the professionalism in which it was conducted suggest otherwise.

However, Georgescu is in fact not unknown to the public. He has held important positions in the state bureaucracy and was the candidate for prime minister of the party called AUR, which became notorious for its open dissatisfaction with having Hungarian minorities within Romania’s border. In the past years he became marginalized both in influential political circles and within the AUR party, because he called the founder of the Romanian fascist movement a national hero on a number of occasions.

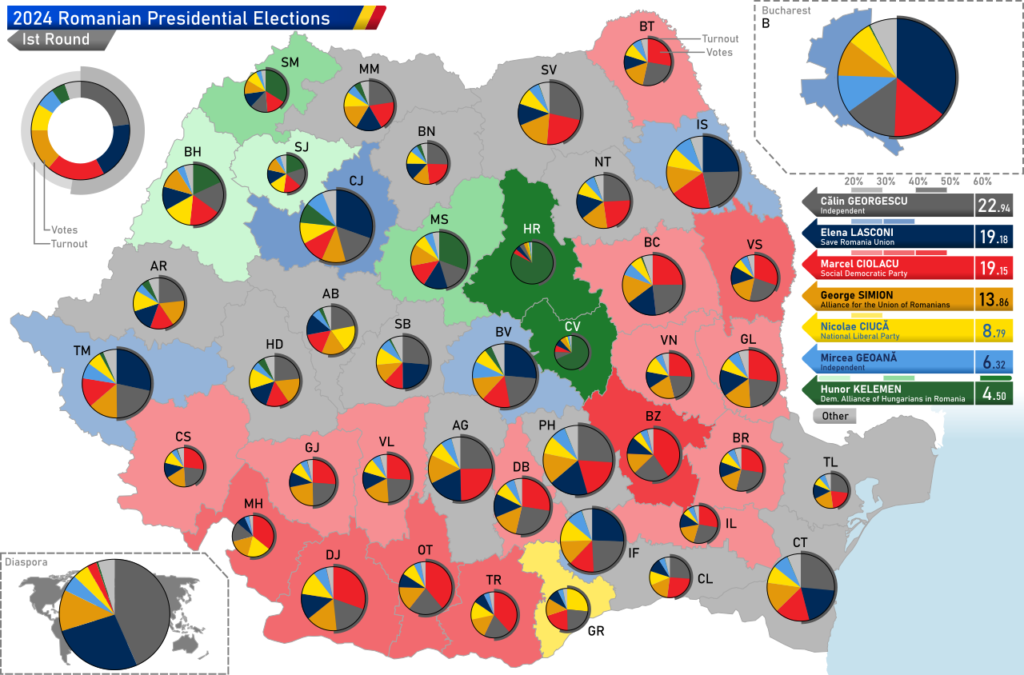

A poll conducted immediately after the election revealed that a significant portion of Călin Georgescu’s electorate consisted of young or middle-aged people, who potentially worked abroad or are currently living outside of the country’s borders. Most of the Romanian diaspora—which represents 15 per cent of all Romanian citizens—voted for him, but within the country, no clear trend has emerged. For example, one of the poorest counties supported Călin Georgescu, but so did some of the most developed ones as well, such as Arad, Constanța, and Nagyszeben (Sibiu). These are regions known for their economic significance, prestigious universities, naval ports, and modern industrial bases.

💰🎓 In 2022, there were wide variations when looking at the rate of young people neither in employment nor education or training in the EU.

— EU_Eurostat (@EU_Eurostat) May 26, 2023

This ranged from 4.2% in 🇳🇱the Netherlands to 19.8% in 🇷🇴Romania.

What about your country❓

👉 https://t.co/h6tUJoWPYC pic.twitter.com/oKtqGwR2ru

The voting patterns become more revealing when they are analysed within individual counties. Take Constanța County, for instance: in the urban centre—Constanța, the port city—the liberal candidate secured a majority. However, in the surrounding Administrative-Territorial Units (ATU)—which consist mostly of small towns and villages—Georgescu and other ultranationalist candidates won.

The phenomenon is also apparent in counties such as Brașov, Timiș, and Iași, where most the voters favoured Elena Lasconi, a liberal candidate who will face Georgescu in the second round of the presidential election. It is also not uncommon in counties won by either Georgescu or Lasconi to see these two candidates in the top two or three positions among the fifteen contenders.

The Reasons Behind Georgescu’s Rise

This raises an important question: why did voters in small towns and villages close to big urban areas choose to cast what they called a “protest vote” against the system? They have actually benefited from the large infrastructure projects carried out by the state and the substantial inflow of FDIs concentrated in major cities. This meant new residential parks, shopping malls and factories. The number of construction projects kept rising in 2023 compared to 2022), even though inflation rose to over 10 per cent. In 2023 the base interest rate rose by 5 percentage points, the economy had been in recession since 2020, and the urban population was shrinking.

All this meant lucrative business opportunities and growing affluence for many years. Local governments, politicians, banks and a significant portion of the population were pleased that progress and prosperity had finally been brought to the country and new business opportunities opened up.

Companies and people from the middle class started to sell or buy properties at ever-higher rates. As a consequence, however, the cities that had become the economic powerhouses of the country also experienced elevated expenses for groceries, restaurants, healthcare, and other daily necessities, further squeezing household budgets.

Secondly, this economic model did not create jobs for most of the people. Developed regions require highly skilled professionals with university degrees, not manual labour. Nowadays few people work in factories, and these kinds of jobs often require special training. A shown in Table 1, less than 20 per cent of the population has higher education, and less than 20 per cent of those employed are managers or professionals.

Education level and place of residence

| Category | Total | Men | Women | Urban | Rural |

| Total persons aged 25–64 (million persons) | 10.074,2 | 5.056 | 5.018,2 | 5.319,6 | 4.754,6 |

| Higher (college and university education, PhD, post-PhD, post-university studies) | 18.6% | 16.6% | 20.6% | 29.4% | 6.6% |

| Secondary (post- secondary, secondary school, vocational school, trade school) | 61.8% | 64.9% | 58.6% | 62.0% | 61.5% |

| Primary (elementary school, no completed education) | 19.6% | 18.5% | 20.8% | 8.6% | 31.9% |

The rural population has fewer chances of acquiring well-paying jobs, as economic development in these areas remains limited. A national survey conducted by the National Statistical Institute showed that 96 per cent of young adults wished to work more hours, but they don’t have an opportunity to do so. In addition, access to higher education and vocational training is also limited in these areas, which is a significant barrier for upward mobility.

But living in Romania was never a guarantee of a comfortable life. As of 2021, Romania is the second most unequal society in the EU based on its Gini Index. In 2022, poverty or social exclusion (referring to those earning less than 60 per cent of the national median income) affected half (50.1 per cent) of the rural population. This is 34.4 percentage points higher than the rate in urban areas. This is alarming given that Romania’s population of 19 million is 54.67 per cent rural and 45.33 per cent urban.

In 2022, 15 per cent of Romanians were unable to heat their homes adequately during winter, a 5-percentage-point increase from the previous year. Around 10 per cent of the population lives in buildings with leaking roofs or other structural damage, and 21 per cent of households lack basic sanitation facilities like a toilet, shower, or bathtub—far above the EU average of 1.5 per cent. Adding to this, Romanians live in relatively crowded conditions, with only 1.1 rooms per person, compared to the European average of 2.6 rooms per person).

Clearly there are plenty of reasons why people try to escape these conditions, but they face fewer and fewer possibilities to do so. Western European countries, which were the destinations for decades for Romanians seeking a better life, have become less welcoming in the past years, as they are grappling with their own deep economic and social problems.

It is no wonder therefore that relatively large swathes of Romanian society see Georgescu as a figure who may bring about change, resulting in economic prosperity. It remains to be seen whether his radical nationalist and far-right rhetoric and agenda will convince the majority this coming Sunday.