The facts are these. On April 23, the village of Nag al-Fawakher, a small rural locale in the outskirts of the city of Minya in Upper Egypt, became the site of an atrocity. At approximately 9 PM, a large group of extremists – large enough to comprise a significant proportion of the local population – assembled outside of civilian homes inhabited by the local Coptic Christian minority, chanting ‘Allahu Akbar’ (God is greatest) and ‘Allahu A’adham’ (God is supreme).

The mob demanded that the Christians living there come out from their homes—a request which, perhaps understandably, was denied. Within short order, the assembly, which had now taken on the characteristics of what Westerners would typically call a ‘race riot’, proceeded to set fire to the Christian domiciles, while their inhabitants were still inside.

The screams of fear and desperation from those locked inside their burning homes had little effect on the mob, which dispersed only after security forces arrived an astonishing 90 minutes later. No less than 4 civilian homes occupied by Christian families were burned down. Some homes were apparently looted, with valuables such as gold and silver, but also more trivial household goods like gas cylinders being stolen by the riotous mob. By the following morning, the worst of it seemed to be over. The mob had been dispersed, security forces were on-site, and some of the perpetrators had been taken into custody, with others actively sought for arrest. But by no means is this a happy ending, nor a cause for catharsis.

In the most blunt and frank terms, what happened in this small village just outside Minya was an act of attempted murder. It was a race riot. It was mass arson. It was an act of hate perpetrated with murderous intent against innocent Christians. All we have left to ask is: how did it happen, and who is to blame?

enggeogy sharqawy on Twitter: “الهجوم علي منازل المسيحيين بالاسلحه والحجاره وتدمير اجزاء من المباني بعد صلاه الجمعه بقريه الكوم الاحمر #المنيا و الاستعانه بتعزيزات قريه الفواخر للاحتواء .اين العمده عواد عقيله و والدة؟ ماذا يحدث خلف الكواليس !ان الاوان لنزول الجيش🤚صعب ندخل اسبوع الالام والقيامه بهذا المشهد! pic.twitter.com/1CjtG2fwOB / Twitter”

الهجوم علي منازل المسيحيين بالاسلحه والحجاره وتدمير اجزاء من المباني بعد صلاه الجمعه بقريه الكوم الاحمر #المنيا و الاستعانه بتعزيزات قريه الفواخر للاحتواء .اين العمده عواد عقيله و والدة؟ ماذا يحدث خلف الكواليس !ان الاوان لنزول الجيش🤚صعب ندخل اسبوع الالام والقيامه بهذا المشهد! pic.twitter.com/1CjtG2fwOB

video footage of second riot in Egypt against Christians

Egypt and Anti-Christian Violence

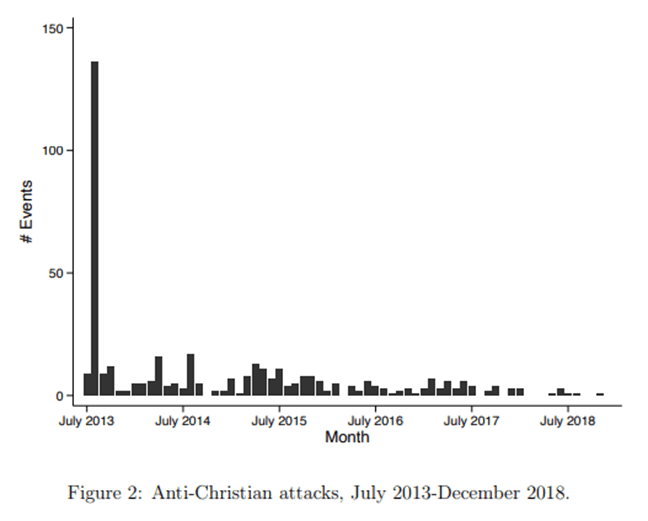

Anti-Christian violence is rarer in Egypt than in most other countries in the MENA region, but is no less devastating in its consequences. In recent Egyptian history during the 21st century, two inflection points for anti-Christian violence stand out in particular: the period of communal violence that followed the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, and the period of planned terrorist attacks following the declaration of an Islamic State in Iraq and Syria in 2014.

The first inflection point came in the immediate aftermath of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, when 30-year president Hosni Mubarak was deposed from office by popular demand. The fantastical success of the revolutionaries was not reflected in their management of Egypt’s newfound democracy—something that became apparent when the Muslim Brotherhood-backed FJP candidate Mohamed Morsi won the subsequent elections and became Egypt’s new president.

This was followed by a period of chaos and social anarchy that was impossible to predict, let alone control. Islamists assumed that the new regime would endorse their expropriation of infidel property. Secularists, threatened by the new regime, took to the streets in violent opposition to its dictats. Christians, predictably, suffered in the midst of the maelstrom. In his book Motherland Lost: The Egyptian and Coptic Quest for Modernity, author Samuel Tadros describes the adverse circumstances faced by Copts as follows:

‘Copts in small villages were increasingly forced to adhere to the Islamists’ standards and vision enforced on the ground… The most worrisome aspect for Copts remains the participation of their neighbors, coworkers, and people they had grown up with in attacking them.’[1]

This account seems at first to match what took place last week in Nag’ el-Fawakher, which as mentioned, lies on the outskirts of the city of Minya. But a closer look suggests otherwise.

A recent study on sectarian violence in Egypt by authors Barrie et al.,[2] first published in Cambridge University Press, shows that attacks by unaffiliated civilian mobs against Christians dropped precipitously from 2013 onwards, declining consecutively each year after that. By established metrics, the attack on Christians in al-Fawakher should not have happened; yet it did.

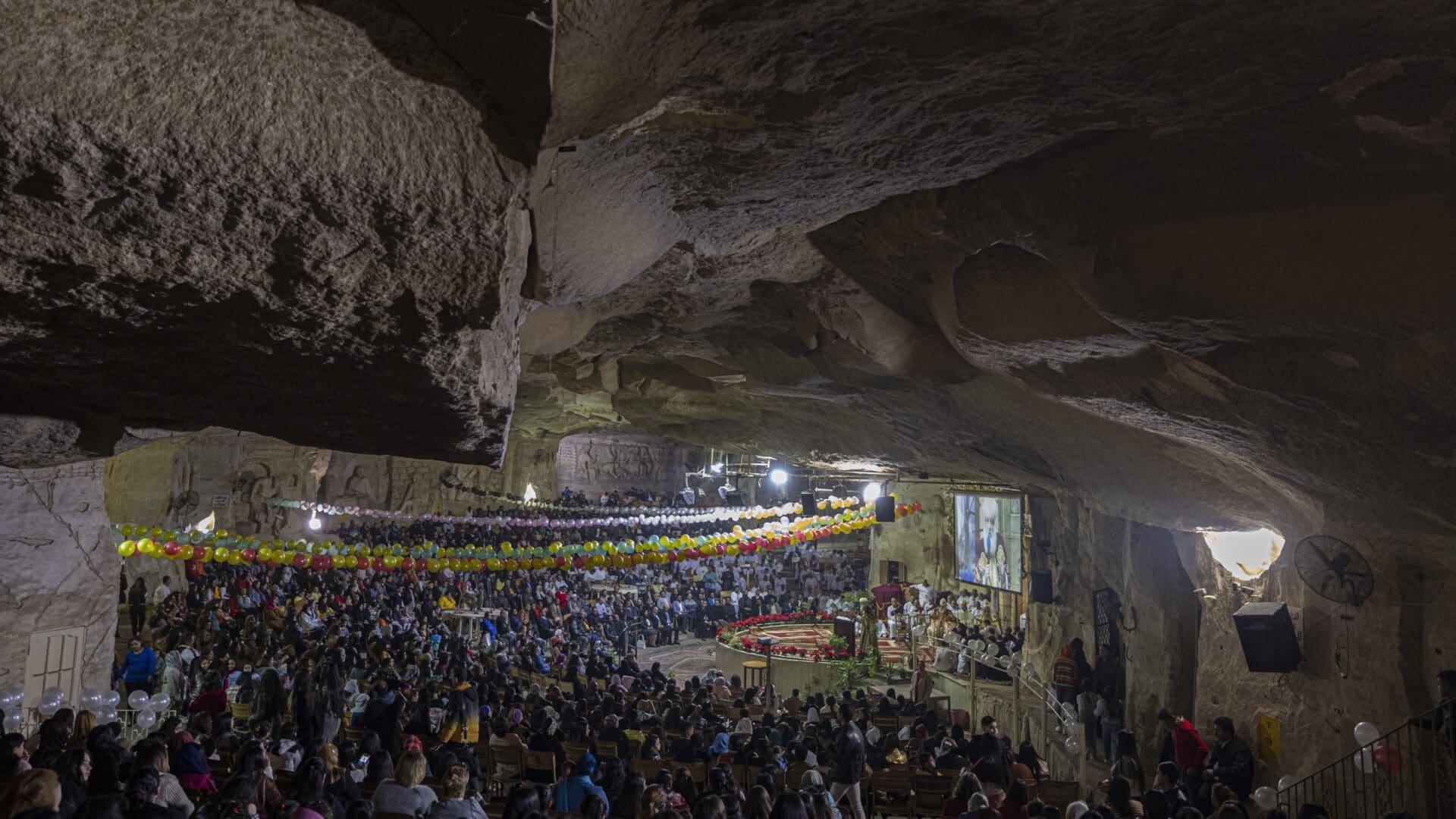

Not only is Minya one of the most populous and economically vibrant cities in Egypt—it is also one of its most Christian cities. Approximately 50% of Minya’s residents confess the Christian faith, according to Egyptian data.[3] Nag al-Fawakher is approximately 12 kilometers, or a little over 30 minutes’ drive from the city center, putting it in commuter range for those residents who work in the city proper.

None of this makes sense. If anti-Christian violence is declining steadily, if Minya is a city where Muslims and Christians have lived in coexistence for over 1000 years, and if al-Fawakher is a small village on the outskirts of town far removed from sectarian politics, how on earth could this have happened?

Technological Violence

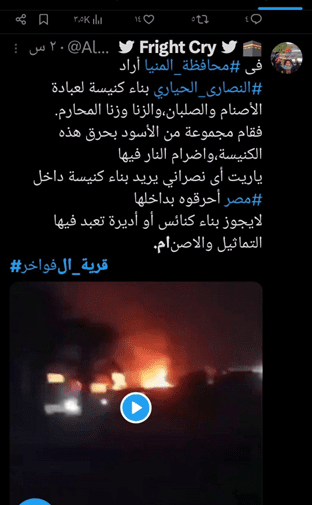

Last week’s violence in Minya started long before April 23. According to credible local sources, the villagers were antagonized by the weekly visitation of a Coptic Orthodox priest to a local civilian house, which was used for Mass on a weekly basis. This was a necessity for the Christian residents of the village, as many residents do not have vehicular transport, and the closest church is located some kilometers away. A rumor arose among the villagers, spreading like wildfire on local Facebook and WhatsApp groups, that the house used as an ad-hoc site for weekly mass was planned to become a full-scale Christian church in the future. Simply put: the locals believed in a conspiracy theory, that the Christian community was conspiring to take over their town. What came next needs no repetition.

In previous eras, galvanizing an entire town or village to acts of violence against a minority group would have been a difficult endeavor. Today, this difficulty has vanished. Social media allows for local town or village populations to form decentralized communicative channels where users can hype others up into a frenzied state. And this phenomenon is by no means uniquely Egyptian.

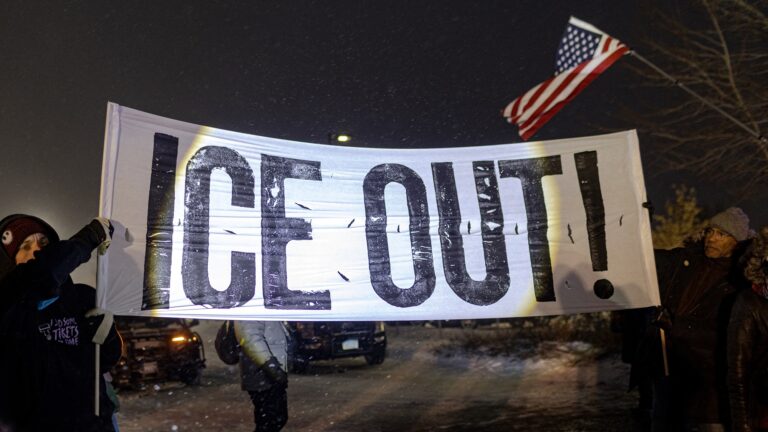

The January 6 Capitol Riots, the 2022 episodes of interethnic violence in Myanmar, as well as more recent outbreaks of intercommunal violence in Ethiopia, have all been linked to the use (and misuse) of social media platforms. In the context of anti-Christian violence in the MENA region, the increasing prominence of social media platforms marks a significant break from the past. Unlike the 2010s where extremism was disseminated from centralized sources that could be located and shut down with ease, recent years have seen the proliferation of decentralized and autonomous groups on platforms like Facebook, Telegram, and others.

The core problem here is the fact that the users of these platforms outside of the Western World are often decoupled from anything close to the kind of moderation we have come to consider normal within the Anglospheric internet domain. In the aforementioned case of Myanmar for example, where it is reported that ‘social media is Facebook, and Facebook is social media’ local community groups can quickly turn toxic, hateful, or even violent when unmoderated. What makes the Burmese case so perverse is not Facebook’s provision of echo chambers to wilful participants, but rather the fact that Facebook’s algorithms ‘proactively promoted violence’ against minority groups, simply by default. There was never any conspiracy by these platforms to facilitate mass murder in Myanmar, Egypt, or anywhere else. Rather, by virtue of their basic operational models and attention-seeking algorithms, they create a context in which such horrors can become the inevitable outcome.

Speaking to Ghaffar Hussain, a leading British expert in deradicalization and extremism with decades of experience in his field, I heard the following explanation, ‘Social media platforms have developed a business model in which algorithmic amplification is used to usher users into political silos in which they are exposed to more and more extreme content. This is something extremist groups can exploit to recruit vulnerable people.’

Hussain is correct in describing the capability of these platforms to act as ‘silos’, ushering users into increasingly extreme bubbles of groupthink, becoming more and more vulnerable to the suggestions of malevolent extremists. On the other hand, there is no indication that any extremist group, of any affiliation, had any hand in the burnings of Christian homes that took place in Nag’ el-Fawakher. What this incident appears to be, by contrast, is an outbreak of violence exploding out from the internet into the real world with devastating consequences.

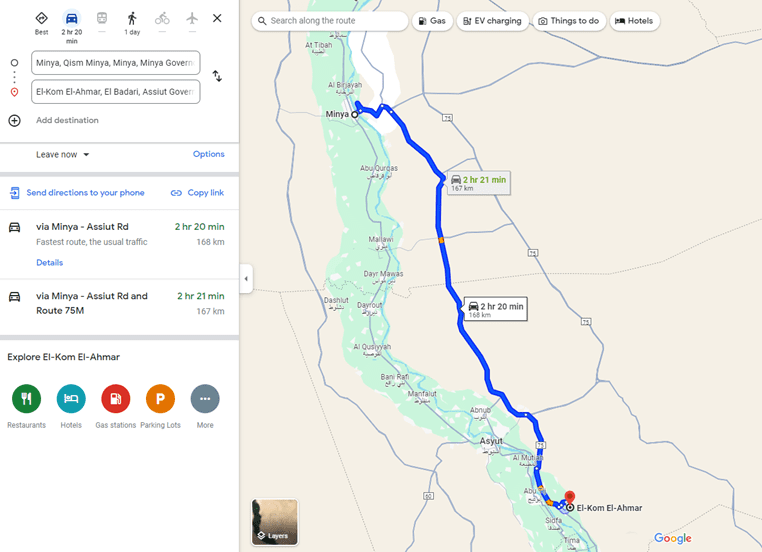

Support for this hypothesis can be found in last week’s violence itself. While April 23’s attacks on Christian homes occurred close to Minya city, a second spate of attacks against an Evangelical community took place in El-Kom El-Ahmar; roughly 130 kilometers away from the initial site of the attacks. These two communities, located hours apart if driving with optimal conditions on the rocky roads of Upper Egypt, have absolutely nothing to do with each other.

Rather than an extremist group exploiting a social media platform to recruit vulnerable people, what took place last week appears to be quite the opposite. Decentralized local communities, far from governmental reach, are utilizing social media platforms to hype themselves up into a state where riotous violence becomes a necessary consequence. The ultimate conclusion to this sad series of events is that Egypt, as a centralized authority, is struggling to monitor these autonomous decentralized social media groups, and therefore these ‘Islamic vigilantism’ incidents may continue to occur.

Finally, I spoke with Medhat El-Banna, President of the MENA Forum, who was deeply sympathetic to the plight of the Christian communities affected by last week’s violence. He told me that ‘What we need right now, urgently, is to modernize and improve the Islamic discourse in Egypt’. Surely, he must be right. The alternative is to accept that intercommunal violence of the kind we witnessed last week in Upper Egypt is simply the ‘new norm’ we should accept.

[1] Samuel Tadros, Motherland Lost: The Egyptian and Coptic Quest for Modernity. Hoover Institution Press Publications. Chapter: The Bitterness of Leaving, the Peril of Staying

[2] Christopher Barrie, Killian Clarke, and Neil Ketchley, ‘Burnings, Beatings, and Bombings: Disaggregating Anti-Christian Violence in Egypt, 2013–2018’, Perspectives on Politics. Published online 2022:1-20. doi:10.1017/S1537592722002730

[3] Al-Ahram, Issue No.43948, 4 April 2007