The European Convention on Human Rights, which deals with freedom of thought and conscience states:

‘Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs shall be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public safety, for the protection of public order, health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.’ (Art. 9, 2)

This article essentially recognises that, notwithstanding a person’s right to exercise or not exercise their religious belief, if the body politic of a country judges an individual’s or a group of persons’ religious expression to be a threat to the order of its society, it could curtail the freedom of religious expression and even penalise those in question as it sees fit.

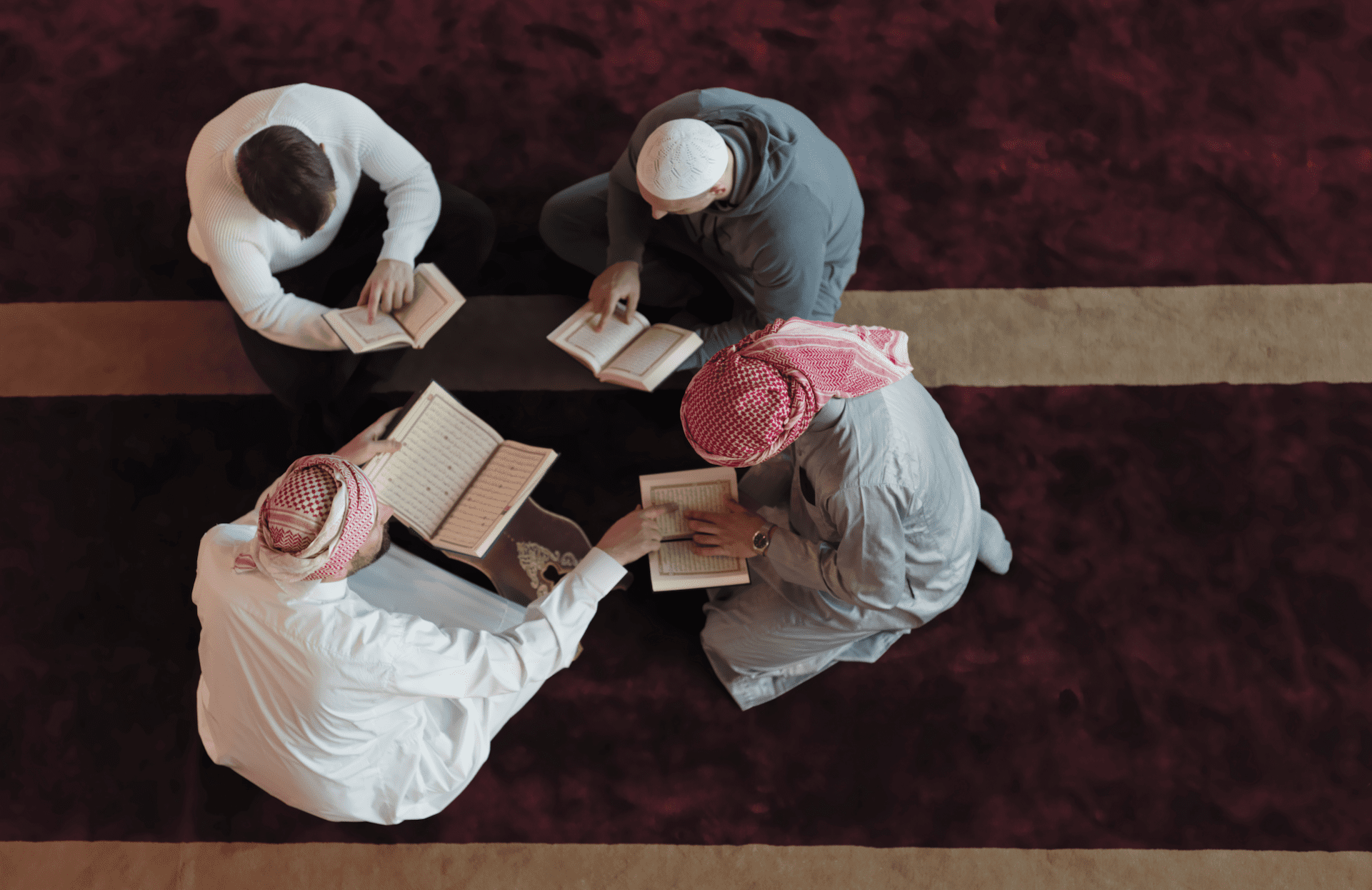

Recently, the city of Grenoble was in a litigation over Muslim women wearing the burkini as swimsuits in public. As explained by Soma Hegedős in his article Muslim Religious Clothing in the Context of Religious Freedom, ‘it is not only in France that there are legal disputes over Muslim garments: in Europe, the issue has been a challenge since the 1990s, with European courts in Strasbourg and Luxembourg having passed several rulings on such cases.’

France is often accused of being Islamophobic because of its ban on the burqa and religious symbols such as headscarves in public schools

France, home to Europe’s largest Muslim population, is often accused of being Islamophobic because of its ban on the burqa and religious symbols such as headscarves in public schools. Muslims hold that this is a direct violation of their freedom of religious expression. Yet the defenders of French secularism say this is a fundamental misreading of laws which aim to keep religion out of public life. Does the Grenoble decision, which is identical to other laws in Europe, contradict the EU’s Convention on religious freedom?

The city of Grenoble’s norms approved in May, without naming the burkini, allow people to wear any kind of swimwear, including letting men or women fully cover their body or allowing women to go topless in the same way as men can. Eventually, the local court upheld France’s full ban on wearing the burka or Islamic headscarf in public places, thus sustaining that the contrary would violate French secular laws.

The point to be made is that freedom of religion for Muslims is an altogether different concept from the Christian one, which embraces the separation between institutionalised religion and state, whereas Islam does not.

Freedom of Religion as a Political Right

Society, which is composed of individuals, is organised as the State itself, but it is limited in its governmental powers because government exists to carry out certain functions relative to the needs of society.

The late John Courtney Murray, S.J., who drafted the Vatican II Declaration on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae (1965), made this clear: ‘the issue of religious freedom arises in the political and social order—in the order of the relationship between the people and government and between man and man.’[1]

Referring to the separation of church and state as detailed by the First Amendment to the US Constitution—‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof’—Murray elaborates:

‘The American thesis is that government is not juridically omnipotent. Its powers are limited, and one of the principles of limitation is the distinction between state and church, in their purposes, methods, and manner of organisation.’

This is because in some of the former American Colonies and subsequently some states of the United States of America, institutionalised religion was enforced on Americans. In Virginia, for example, if one did not publicly adhere to and financially support the Anglican Church, which then became the Episcopalian Church, the State had the power to deprive the individual of their rights and privileges, such as holding public office or maintaining an occupation—in certain cases even children could be taken away from their parents if they did not raise them Anglican/Episcopalian. It was such excesses that prompted Thomas Jefferson to advocate for the separation of church and state in his Bill of Establishing Religious Freedom (12 June 1779).[2]

Freedom of religion, however, does not mean that individuals may solicit “rights” in opposition to truth or demand “freedom” that would contradict the natural law, such as those claimed by the LGTB+ movement.

Benedict XVI once said that there can be a peaceful co-existence between Christians and Muslims, if there is mutual respect and an open dialogue which focuses on the common values of human nature. Religious freedom, which is a social and political dimension indispensable for peace, promotes co-existence and provides a harmonious path for a shared commitment in the service of noble causes, as well as for the quest of the truth, which does not impose itself through violence, but by its own strength.

The dilemma is that certain religious-based tenets in Islam, like those found within sharia law, not only pose a danger to individuals, but threaten the common good of society.

The Dilemma of Islamic Religious Expression

Islam, historically speaking, developed as both a sect and as a political and religious commonality without any bureaucratic institutions or clergy. It was a populace in which the Prophet Muhammad was the one and only authoritative narrator and interpreter of a divine and transcendent law that governed all human activities; it was an egalitarian and undifferentiated institution set under the auspices of an individual who did not legislate but instead narrated what he claimed was God’s revelation.

As explained in Islam: Religion of Peace? – The Violation of Natural Rights and Western Cover-Up, Islam evolved from a simultaneous establishment of a political-juridical structure and an institutionalised set of religious mandates, which instantaneously translated into a theocratic nation. As a monocratic nation-state, it instituted norms making the body politic one and the same with the established religion. Anyone who desires to be a member of the Islamic community is coerced into accepting Muhammad’s socio-political doctrine as their profession of faith.

It is not that religion and State are united; under Islam, the religion is the State and the State is the religion

The Prophet of Islam did not propose a new social doctrine but rather a moralistic exigency, which materialized into an Arab civitas—a self-reliant and independent nation-state—with the mandate to proliferate Allah’s kingdom throughout the whole world, to every nation. The adherent, therefore, in the act of yielding to the tenets of Allah, simultaneously becomes a member of a worldwide faith community established by Allah’s Prophet. By submitting, the Muslim ‘incorporates a religious identity that is both individual and corporate, as well as a responsibility or duty to [unconditionally] obey and implement [Allah]’s will in their personal and social lives.’[3] In other words, it is not that religion and State are united; under Islam, the religion is the State and the State is the religion—the gospel notion of ‘Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s’ (Mt 22, 21) is alien to it.

Religious freedom in the Islamic world, which continues to be an almost non-existent topic, requires every believer to follow the sharia. Since the sharia is ‘understood [as] the totality of Allah’s commandments relating to the activities of man,’[4] logically “those who abandon the [Islamic] community by converting to another religion or by becoming atheists are considered traitors and therefore lose their rights’ or even their very lives: ‘Whoever changes his [Islamic] religion, then kill him.’ (Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 84, hadith 57)

One should then not be surprised at the repetitive efforts of Muslims to religiously manifest themselves any more than at westerners’ concerns thereof. The author does not have a problem with Muslim women sporting a headscarf any more than a Jewish man wearing a yarmulke. The issue is not the expression of religious beliefs by Islamists, rather the socio-political predicaments that come along with it.

[1] Walter M. Abbot, S.J., The Documents of Vatican II., Piscataway, America Press, 1966, p. 676.

[2] The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5, eds. Phillip B. Kirkland and Ralph Lerner, Indianapolis, Liberty Fund, 1987, p. 77.

[3] The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, ed. John L. Esposito, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 144.

[4] Andrew G. Bostom, Sharia Versus Freedom: The Legacy of Islamic Totalitarianism, New York, Prometheus Books, 2015, p. 111.