Henry Kissinger is nothing short of a legend of international relations. His name has become indelible from the Cold War history of the United States and of the entire Western world. While serving as the US Secretary of State (as perhaps the most respected person to ever occupy that office), he was the primary architect of the policy of détente towards the Soviet Union under the Nixon administration. He is also well-known for his advocacy for realpolitik, a strategic outlook on foreign policy that puts the pursuit of practical aims and interests in front of morals and principles. So, what does realpolitik dictate now in terms of Russia and Ukraine?

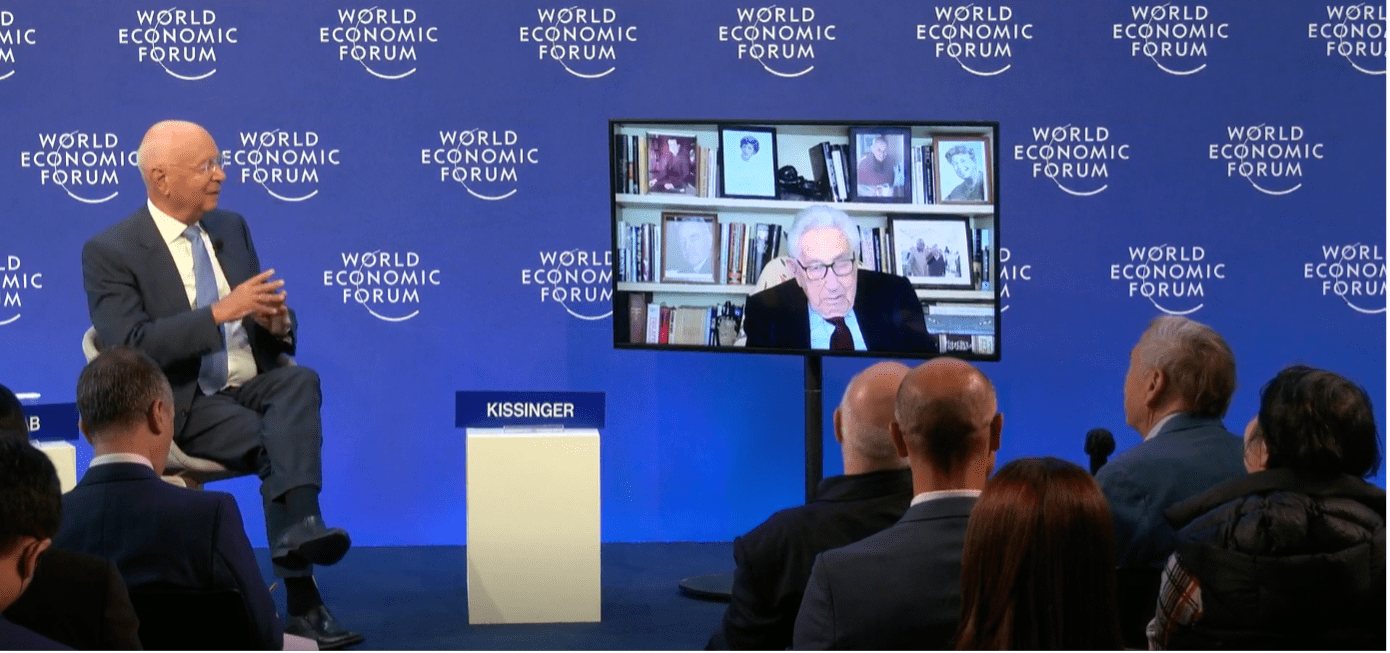

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Kissinger reminded the West of Russia’s historical importance in the European and global security framework, and that it would still be needed post-Ukraine to keep the geopolitical balance. Now that Moscow’s grip on Ukraine is undoubtedly weakening by the day, the former official urged Western leaders not to seek an excessively humiliating defeat of Russia in the conflict, lest Europe’s long-term stability be lost. If effective negotiations do not begin in the next two months, he warned, the West might be unable to deal with the resulting tensions and upheavals. In regards to what he imagines as possible concessions on the Ukrainian side, Kissinger said ‘Ideally, the dividing line should be a return to the status quo ante’ – which means the “previous state of affairs”, referring to the pre-war occupation of Crimea and Donbas, the regions that could become subject to negotiation should Kyiv finally agree to talks. ‘Pursuing the war beyond that point will not be about the freedom of Ukraine, but a new war against Russia itself’, Kissinger added.

‘The dividing line should be a return to the status quo ante’

The restoration of the status quo in Ukraine in exchange for avoiding global escalation seems fairly reasonable and should not sound like a ludicrous idea (after all, those territories had already been de facto controlled by Russia), yet the reactions of world leaders–and particularly of Ukrainian officials–were almost religious shock and disbelief. President Zelensky has long been saying that the conditions for peace talks include the restoration of the complete pre-invasion borders, and recent polls showed that the vast majority of Ukrainians are in favour of their president’s demands and firmly against ceding any territory to Russia, even if that means the war could drag on for years. One Ukrainian MP even calledKissinger’s statements a ‘pity’ and ‘truly shameful’, while Zelensky’s advisor Mykhailo Podolyak responded by sayingthat his country would ‘not trade its sovereignty for someone to fill their pockets’. To be honest, these reactions are quite understandable; Ukrainians are the ones truly affected by this conflict and no one is entitled to tell them how to feel about their own country. But they also speak from a place of emotion and principles, while true statesmanship always requires a touch of realpolitik as well.

And again, Kissinger was not talking to Ukraine, but to the Western leaders, who have seemingly all bought into the plan of completely destroying Russia as punishment for the invasion (and in a strategic sense as well, so that they do not have to deal with the Russian threat on a geopolitical level ever again). The idea is to provide Ukraine with enough weapons and funds to make a stand long enough for Russia to crumble under the economic weight of the sanctions until its regime crumbles under the West’s sanctions and under internal political pressure. Only once Vladimir Putin is gone and a new government takes the necessary steps for Russia to return to the rules-based international system (under Western influence, of course), can there be peace again. But this wager is based on the very fragile assumptions that Putin will fall in the foreseeable future and that whoever follows will be different. Unfortunately, neither of those assumptions are certain to turn out to be correct.

The real struggle of the West in the twenty-first century will be with China

Putin has proved to be unpredictable before, and that is something the West should keep in mind. For instance, we do not know what embarrassment in Ukraine and the fear of a possible coup in the Kremlin would push him to do. For all we know, Putin could follow through with his nuclear threats if he believed all is truly lost to him. But even if we do not go that far, another side effect of the current policies of the West is that Russia is effectively being pushed into the arms of Beijing. The real struggle of the West in the twenty-first century will be with China, and we should be mindful of that when thinking about the post-Ukraine world. Historically, the role of Russia in European geopolitics has been oscillating between being an observer and an adversary, but is also potentially that of ‘the guarantor, or the instrument, by which the European Balance could be re-established,’ said Kissinger, adding that ‘current policy should keep in mind that the restoration of this role is important to develop, so that Russia is not driven into a permanent alliance with China.’

Naturally, neither Kissinger nor I advocate for the condoning of Moscow’s actions or meeting all of Putin’s demands. The invasion of Ukraine is a horrible violation of international standards, as well as an apparent blunder Putin made that must be strategically exploited to a safe degree. What Kissinger proposed was merely setting the negotiation table before the West runs out of options entirely, as well as to keep developments relatively under control and not let the present crisis escalate into something significantly more horrific for all of us. Most critics of his assessment have said that giving up some Ukrainian territory would never result in lasting peace, but would only postpone the bigger war by a few years. Well, this is most probably correct, and I doubt Kissinger didn’t take that into account. We may have already past the point where a larger conflict could be avoidable, and in that case, postponing it does not seem like a bad option at all.

At the Munich Conference in 1938, the Western powers willingly ceded the whole of Czechoslovakia to Hitler. From a perspective of principles, Europe – and especially the Czechs and Slovaks – viewed this move as shameful and even cowardly. But in hindsight–viewed through the lens of realpolitik–it is now regarded as one of the most important decisions that contributed to the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany, as it provided valuable time for the Allies to prepare for the inevitable. Let us hope we are not there yet. But in any case, we should remember what Kissinger said, and let us ‘not get swept up in the mood of the moment’, but let reason prevail.