Monday, 6 February 2023 was a typical day for most of the world. For millions of people in Turkey and Syria, it was a day of nightmares, beginning with an earthquake that levelled cities and ended with a frantic effort to recover the bodies of both the living and the dead. The work is ongoing. Here is why it matters.

——————

It is the 6th of February, 2023, 4 a.m. to be precise. You are at home in your bed in the apartment you own. It is one of many such apartments within the residential building you moved into as a young adult as soon as you could afford to take out the loan required to do so. The building is not particularly impressive, nor is it stylish, but it is at least a home—your home, to be exact. You may not have dreamed of living in such a place when you were younger and more ambitious, nor are you particularly happy about the idea of staying there for the rest of your life.

But nevertheless, this is a space you can call your own—and both you and your young daughter, who has her own room in this two-bedroom apartment, are both perfectly happy to have the safety and stability that this provides.

In about seventeen minutes, while you slumber peacefully, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter Scale will strike Kahramanmaraş, the city where you were born and where you and your family now live.

For 80 seconds, the colossal force will generate energy so powerful that if captured could power all of New York City for over four days.

It is more than enough to destroy a shoddily-erected apartment block such as the one you and your family live in. When this earthquake arrives—and it is only a few minutes away by now—you will feel the ground beneath you shake, shatter, and rupture, swallowing you alive and burying you beneath as much as ten metres (33 feet) of concrete and dust.

While this family is fictional, their story is one that became horrifyingly real across Turkey and Syria in early February of this year. For some victims—those killed in the initial impact at 4 a.m. in their homes and businesses—both the story of the disaster and of their lives ended there. For at least 120,000 that survived with injury, or for millions more who escaped bodily harm but are forced to live on with mental scars, shattered livelihoods, or broken families, this quake was merely the opening chapter of a nightmarish story that continues to this day.

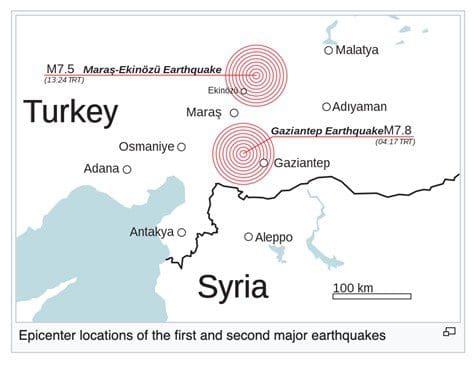

Urban areas closest to the epicentre of the earthquakes, such as Gaziantep and Kahramanmaraş, were hammered by continuous shocks for almost an entire day. Yet the one-two punch of the two major quakes striking seven hours apart was a factor in the disaster’s overall lethality. Within a few hours after the first impact, civilian volunteers and emergency service personnel had already mobilised in nearly every city and town across the region, working to rescue survivors still trapped in the rubble. Another priority was to evacuate people from residential buildings that were still standing in the anticipation of further shocks. By 12 p.m., the most severely devastated neighbourhoods and districts were flooded with survivors and rescue workers, some of whom had begun to re-enter damaged buildings to evacuate immobilised residents or to recover their personal belongings.

It is for this reason that the gap in time between the two strikes so greatly amplified the horror. At 1:24 p.m., without warning, compromised apartment blocks with civilians still inside were flattened. Multi-storey structures came crashing down upon volunteers attempting to rescue survivors in the rubble of adjacent buildings. Torrents of toxic ash, dust, and powdered asbestos flooded entire street squares, spilling out over the open-air emergency medical sites set up some hours before. This second strike, and its timing, had an impact comparable to twin car bombings, which are well-known traumas in the region. In twin bombings, a first explosion is set off in a public area, attracting volunteer rescuers and first responders as well as crowds of onlookers—the true intended targets. A far bigger explosion goes off a few hours later, killing both first responders and locals alike. It is a cruel irony that people living in fear of terrorist attacks were beset by a natural disaster that resembled this terrible playbook.

At present, the twin earthquakes have left over 50,000 people dead, and more than 120,000 injured. These figures will likely increase in the coming weeks, as the disaster itself is far from over.

Over 6,000 aftershocks have been recorded since, many of which produced more fatalities. Feelings of grief, helplessness, and pain have become ubiquitous fixtures for social media users from Turks and Syrians alike. Videos of victims and survivors crying out to their government for answers are now a staple of viral content in both countries.

The post-disaster discourse revolves around just one burning question: how could this happen, and why were we not protected?

Natural disasters, while unpreventable, can still be mitigated, as earthquake-prone cities like San Francisco, Tokyo, and Santiago have shown. Turkish law upholds standards based on those of California, and has done so since 1999—yet little sign of that can be seen in the catastrophic aftermath of this disaster.

So what, many ask, went wrong?

The question as to why buildings in this earthquake-prone region were not made safe or resilient in the event of a disaster is now at the forefront of social consciousness in both Turkey and Syria. Having been ravaged by war and bombings for more than a decade, Syria is in no position to enforce rigorous earthquake-resilient building codes, especially in its north and northwest regions which are occupied by foreign forces or terrorist groups, hostile to the regime in Damascus.

In Turkey, however, regulations for the mitigation of earthquake damage did indeed exist. Yet apparently, these were not enforced or maintained in the afflicted southeastern area of Turkey, where the Kurdish ethnic minority just so happens to be heavily concentrated. While there is no evidence to suggest that building code laxity is connected to ethnic discrimination against Kurds by the Turkish government, there are some within the Kurdish community who have begun to promote this view on social media, to the government’s displeasure.

Beyond recovery, both Syria and Turkey now face a new set of problems as a consequence of the earthquakes. Whether the divisions that are already being created and expanded within society, or the hostile forces seeking to take advantage of this disaster in other ways, there is now a multitude of new threats looming on the horizon. For the victims of this catastrophe in the Northern Levant, as well as rescuers and aid workers seeking to help them, the greatest fear is to be caught in the crossfire. Such dangers are covered in a continuation of this story, which is written by my colleague Logan West.