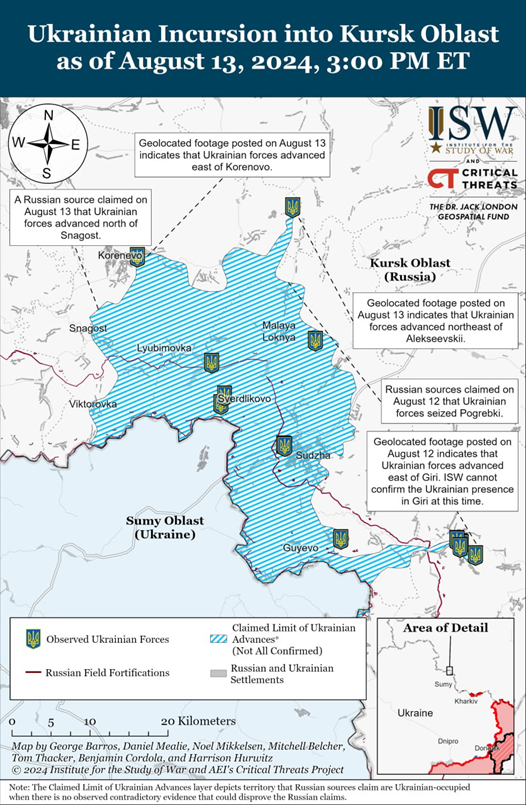

On 6 August Ukraine launched an unprecedented incursion on pre-2014 Russian territory and has been ravaging parts of the Kursk and Belgorod regions ever since.

In the beginning of August, Ukraine caught the world by surprise by invading the territory of the Russian Federation even staunch opponents of the Kremlin consider to be unquestionably Russian—that is, parts of Kursk and Belgorod regions, located within Russia’s internationally recognized 1991 borders. Until now, Ukraine has only been engaging in probing paramilitary raids in the region; as opposed to that, the current attack involves a formidable force, possibly with armoured vehicles, directly controlled of the Ukrainian army.

Despite alarmist headlines, there are reasons to assume that the fears of escalation are unjustified.

In fact, both Ukraine’s desperate actions to bring the war to the Russian populace and the humiliation inflicted on Russia by demonstrating its inability to push Ukrainians back to behind its 1991 borders might actually signal the war is heading to an end. As neither side seems to be able to decide the outcome of the conflict with military means, the Ukrainian attempt can be interpreted as a last effort to capture more bargaining chips before the inevitable peace talks.

Albeit part of Ukrainian society is invigorated by the videos and photos their soldiers are posting in the seized Russian villages, Ukraine’s ‘numbers problem’ has not disappeared—the army is still lacking manpower. Regardless of how many desolate border villages fall into their hands, the math does not add up for Ukraine. The only plausible justification for the attack experts have come up with is that Ukraine wants to exchange the seized Russian territory for Russian-occupied lands, as well as to force Russia into withdrawing some of its troops from the Donbass, where Ukraine’s position is the most precarious, in order to repel the Ukrainians from Kursk and Belgorod. But to the objective observer the invasion seems more of a desperate, last-ditch escapade with vague prospects than a well-thought-out plan with a clear objective in mind.

The second objective that might be behind the incursion is to undermine the legitimacy of the Russian leadership. However, this goal is difficult to achieve. It is true that thousands are fleeing the border regions with nowhere to go; displaced people only get meagre payments only in compensation from the government—10,000 roubles as announced by Vladimir Putin, which is equivalent to 115 USD. This contributes to the overall chaotization of Russia, where there has been a rapid increase in serious crimes since the war started, with uncontrolled migration, the influx of weapons and the return of mentally traumatized war veterans only making the situation worse. This goes against the core narrative of Putin’s legitimacy—the one of a strong leader who is the token of security to Russia. Nevertheless,

tarnishing Putin’s reputation among ordinary Russians is not an easy task.

The Ukrainian attacks are not kept on top of the news cycle by the Russian (propaganda) media, and as people’s main source of information is not keeping them informed, there is no real popular awareness about the issue in the Russian society. On the other hand, the regime has already proved that such incursions can be effectively used to justify the need to ‘carve out a buffer zone’ in Ukraine, near the Russian border—Putin used a similar line of argument earlier this year when justifying the offensive against Kharkiv.

Connected to Ukraine’s apparent objective of undermining Russia’s self-assurance is the symbolism of the attack. The incursion started on 6 August, very close to the tragic accident of the Russian nuclear submarine K-141 Kursk. The submarine sank in the Barents Sea on 12 August 2000, with the whole crew, 118 members of the Russian Navy, dying in the sinking vessel. Many have argued that with the date of the incursion Ukraine is reminding the Kremlin of this rather inconvenient episode.

Kyiv has demonstrated earlier its willingness to use symbolic dates for its attacks. The strike on Russian-occupied Sevastopol, Crimea, in which five civilians (among whom, according to Russia, two children) died due to the falling missile fragments, happened on 23 June, that is, on the first anniversary of the late Prigozhin’s march against Moscow. Russia claimed that ATACMS were used during the attack; just before the strike on Sevastopol, Washington was reported to have given a green light to Ukraine to use US weaponry in attacks against targets in Russia. With such symbolisms, which are arguably also PR ploys, Kyiv may also be hoping to revive Western enthusiasm that seems to be flickering out.

Be it a PR move or an attempt to secure bargaining chips, Ukraine’s incursion and its aftermath very much reinforce the impression that both sides have lost momentum in this war, and they are unable to reach settlement by military means.

Related articles: