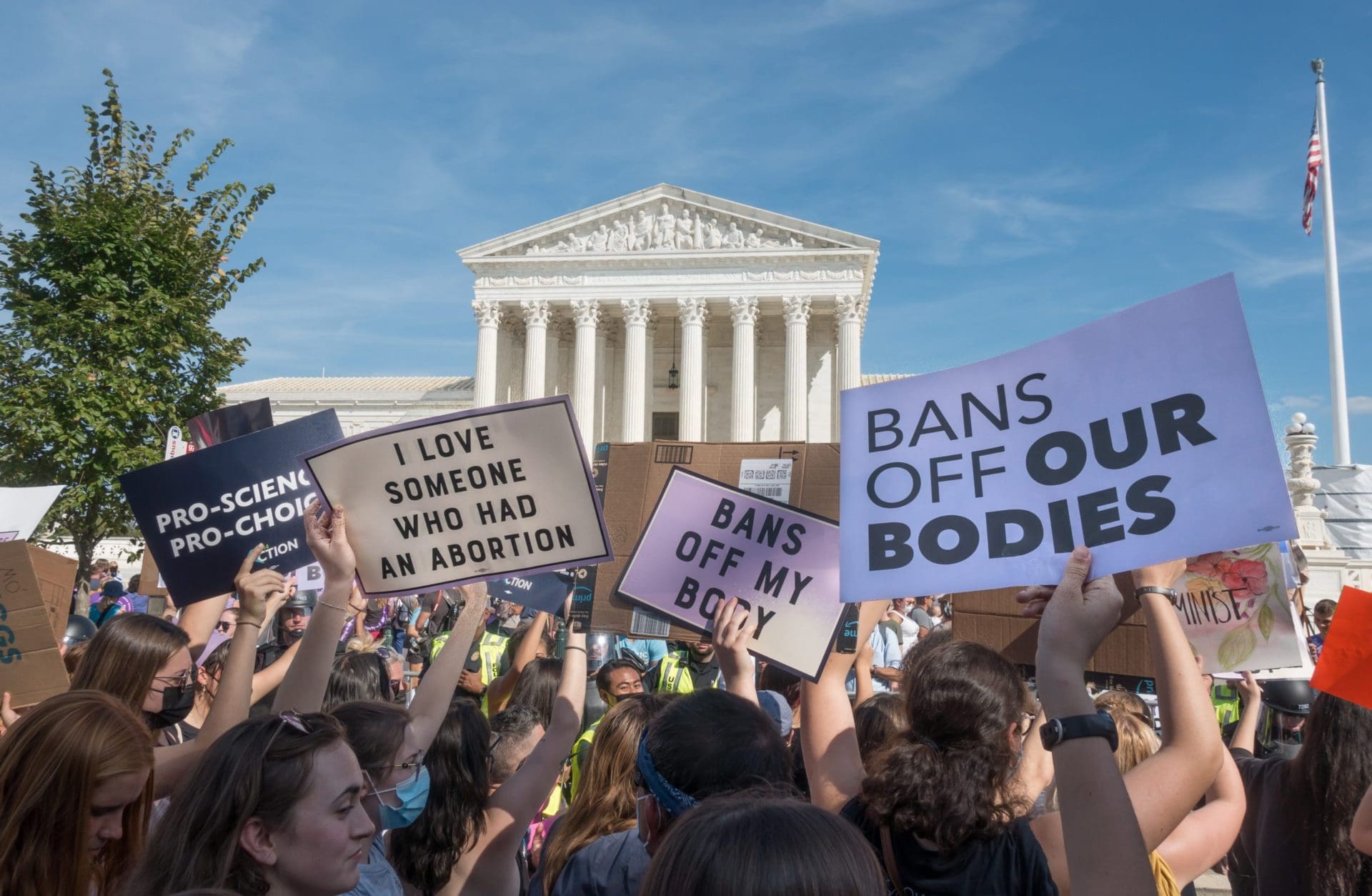

The US Supreme Court, in a 5-4 ruling, eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion, overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision and leaving the question of abortion’s legality to the individual states.

The Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization upheld a law from Mississippi that bans abortion after fifteen weeks of pregnancy, roughly two months earlier than what has been allowed under Supreme Court precedent dating back to Roe.

While the Court’s decision is a watershed moment for unborn children to have their inherent right to life protected, NGOs like the United Nations still insist a mother is entitled to ending her child’s life since children in their mothers’ wombs are not considered human persons.

Man’s dignity and worth are the founding premises of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), not to mention that Article 55 of the UN Charter requires States to promote and encourage ‘the principle of equal [human] rights’. Yet nowhere does the Charter define precisely what these rights are. This is because, as reflected by the wording of the UDHR, the natural rights which were universally declared have no absoluteness, since they are not based on moral natural law and therefore are subject to provisos. Such is the case with the Convention of the Rights of the Child.

The Convention of the Rights of the Child

The Convention in 1989 declared that ‘[e]very child, without any exception whatsoever, shall be entitled to these rights [i.e., protection to live as a dignified person], without distinction or discrimination on account of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, whether of himself or of his family.’

The Convention also calls for a ‘universal respect for the rights and duties of parents in providing religious and moral guidance to their children.’ Yet as per Article 14: ‘Children have the right to think and believe what they want and to practise their religion, as long as they are not stopping other people from enjoying their rights. Parents should help guide their children in these matters.’

Aside from the fact that a child, at least in the pre-pubescent age, is limited in making a mature and conscientious decision, Art. 14 not only contests the parents’ right to and obligation of raising their children under the laws of God, but it gives great leeway to the child to rebel from a religious upbringing, regardless of age. This ultimately divides the family into individuals independent from each other, each being allowed to do as he or she pleases, instead of consulting with one another as to what ought to be done.

Article 1 is silent on the age at which childhood begins

No ethically compelled person can deny a child protection under the law, which includes the right to be properly raised, equal opportunity to education and tutelage against any form of violence or abuse. However, while Article 1 of the UN Convention classifies that a child is any human being under the age of 18, it is silent on the age at which childhood begins, and unclear regarding whether the rights reserved to children under the Convention apply to the unborn.

The complexity is that while the original Declaration of the Rights of the Child (1959) stated that ‘[the child] shall be entitled…[to] special care and protection shall be provided both to him and to his mother, including adequate pre-natal and post-natal care,’ Article 1 of the Convention tends to juridically override it, thereby leaving the question of when life begins up in the air. Such obscurity therefore leaves the unborn child to the whims of the legislator or judge, since it is unclear whether life begins at fertilisation or at conception, or at birth.

The juridical parting point is how life is defined by pro-abortion advocates and justices. The term life is semantically poor, as is its Latin lexicon (vita), which stems from ancient Roman vocabulary. The Romans, being the pragmatics that they were, did nothing else but Latinise the various Greek terms for life, which are:

- Bios: life, in as much as a being is born and dies in its precariousness and mortality.

- Zoé: eternal life, which has no beginning and has no end. It is a dimension of life which is other than bios, such as divine life. Here, the divine is not subject or destined to life or death. As in Christian tradition, the martyr sacrifices his own life, i.e., he surrenders the bios knowing that he shall find the zoé.

- Psyché: life in motion or movement, for which in certain circumstances human life is more than bios, bringing into play other things, such as character, which cannot be derived from the physical human body.

- Soma: a dimension of life that is inseparable from the bios but which is not reducible to the soma; it can be translated as a body.[1]

It is clear that the ancient Greeks had a subtle perception of the different manifestations of life without confusing them with each other. Therefore, with a philosophical language, all of these meanings were synthesised into one sole word: person. And although the English vocabulary defines life with terms reflecting the aforementioned Greek words, its fixed meaning has been reduced to biological existence. Subsequently, the concept of human life then becomes arbitrary, despite modern technology being able to detect the baby’s heart beat eighteen days after conception and signals from the brain can likewise be observed after six weeks. Therefore, it should be of no surprise that since there is no legal recognition of a child in the mother’s womb as a person, such life can be terminated at any point after before gestation. In like manner, countries like Italy sustain the right of a woman to abort her child in the womb up to the end of the third month of pregnancy because while a foetus is acknowledged to be a living being, it has not developed into a person.

It is quite clear that a child’s life, judging by the wording of the Convention, must be protected at all costs

Again, it is quite clear that a child’s life, judging by the wording of the Convention, must be protected at all costs. However, whether this principle encompasses the unborn child in the mother’s womb, (or, for that matter, a child who survives the process of an induced abortion), is left up to subjective interpretation of what exactly the term “child” means.Arguably, if the drafters intended the term “child” in the Convention to apply to a point before birth, they would have explicitly noted that application in the Article 1 definition.

The United States, thanks to Democrat lawmakers, is one of seven countries where abortion is allowed up to the day of birth: it is the case in New York, Alaska, Colorado, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, and Vermont—the other nations are China, North Korea, Vietnam, Canada, the Netherlands, and Singapore. This is something that the UN, via its World Health Organisation, continues to advocate as a human right under the pretension that women have fundamental rights over their own bodies. And as can be seen by the reactions of US President Joe Biden as well of as of abortion supporters in general to the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, the fight to defend the unborn has only begun. Let us hope, pray, and continue to make it evident to pro-abortion advocates and to the mothers who contemplate abortion in particular, that life begins at conception and that unborn babies have an equal right to life as those of us who have been born.

[1] Francesco D’Agostino, ‘Lecture from the Seminar on Bioethics (Seminario di Bioetica Giuridica – 25069)’, Pontifical Lateran University, Rome,6 October 2015; see also in Francesco D’Agostino, Parole di bioetica, Torino, Giappichelli, 2004, pp. 27-34.