This is an abridged version of the original interview first published on 777.hu.

I met Gyula at the American Hungarian School’s Congress (AMIT) last year. He arrived late and accepted the award recognizing his 20 years of service as school principal with a sad smile. I was shocked to learn that he was returning from his wife’s funeral. Next year when we sat down for this interview, it was the first anniversary of her passing away. I was convinced that Gyula would talk mostly about his family, but he got so deep into his early years, including his immigration to America, and then the history of the Hungarian school, that we almost ran out of time to cover his family— which gave him the main inspiration to fight for his Hungarian heritage.

***

In Hungary

Gyula was born in Budapest in 1943, followed by his sister, Gyöngyike in 1944 while their father, Gyula János Varga was fighting in the war against the Soviets as a military officer. When the Soviets advanced towards the end of the war, Gyula’s father fled with his unit but was tricked into an ambush and ended up in a Soviet prisoner-of-war concentration camp, where he was held for two years. In 1944, the rest of the family fled Budapest amidst the bombings. Their plan was to join their father and flee to the West together, but when they found out that he was in captivity, they returned to Budapest. Gyula’s father was hit by typhus but returned from captivity in 1947. He eventually recovered, but with many health complications. ‘My father was a diligent and intelligent man who spoke six languages. Back in Siberia, he worked for an old watchmaker. He couldn’t get a job upon his return from captivity, but he passed the watchmaker’s assistant exam and was able to find work afterwards. A bit later, he also passed the accountant’s exam and could work as such. Meanwhile, in 1949 my younger brother Zsolt was born. We lived in Márvány Street in Budapest.’

Many retired military officers lived in the area, and Gyula’s parents were married and he was baptized in the nearby Krisztinaváros church. His mother, Klára Bakai worked at the economic department of the 12th district’s head office (known today as the municipality). ‘My first school was the Márvány Street primary school; I will never forget my first teacher, Ms. Piroska. In 1951, our family was deported by the communist authorities due to my grandfather’s military background and connections, and because none of them were party members. They had to evacuate their home with a 48 hours’ notice.’ Together with their maternal grandparents, Alfréd Bakai and Erzsébet Bakay, they had to move to the town of Szikszó, where they spent more than two and a half years, until the so-called ‘amnesty regulations’ of 1953. The seven-member family was crammed into a single room, while another family of four was forced to move into the other room. The communists penalized the house owner’s family, who were obviously upset about it.

Gyula’s grandparents were too old to work, so they took care of the kids while his mother worked as a bricklayer’s helper at a construction site until she was 7 months pregnant. Her baby was born prematurely, and died of pneumonia after five months. His father was initially forced to perform military penal labor, but later ended up in an office doing accounting. Absurdly, while being deported, his father received a letter one day from the government announcing that as a sign of their ‘respect’, he was appointed as a judge, which he ‘sadly’ rejected considering his penal labor duties…

When their deportation ended, they could freely leave, but were banned from returning to Budapest. Since they had no place to live, the family split. The grandparents went to live with their eldest daughter, while the parents got a job in Budapest, but because they weren’t allowed to live within the city, they rented a sublet room in Budaörs (a suburban village adjacent to Budapest) that could only accommodate two. Since their landlord suffered from lung disease, they preferred not to have their children around. Gyula’s sister went to live with her uncle, the boys lived with their grandmother in a tiny room for a while, and then ended up in an orphanage in the countryside, run by former reformed church sisters. (The Catholic and Reformed Church orders, with very few exceptions, were dissolved and banned to operate at the end of the 1940s by the communist authorities).

‘Despite the way the communists treated these sisters…they still cared for and educated children. They were real heroines’

‘I have many fond memories from that time. The sisters had a plot of land on a small island of the Danube, and while they would go over to cultivate it, we often splashed in the river. We would drive the goats of the orphanage out to graze. We played a lot with wooden swords around a castle ruin nearby. Sometimes we went to harvest melons, or we stole fresh sweet corn and roasted it over the campfire. I really liked to read, but when the sisters saw me read pulp fiction, they gave me Christian books instead,’ he laughed. The sisters often didn’t even know what to give the children for dinner. They prayed for long hours in the evenings just to kill time. The villagers, who also didn’t have much, showed up several times unexpectedly, and brought them food. ‘Despite the way the communists treated these sisters (and all other religious people), they still cared for and educated children. They were real heroines,’ Gyula stated emotionally.

After a year and a half, they could reunite with the rest of their family. On a hillside in Budaörs, his parents moved into a dilapidated wine cellar. There was no running water, heating or toilets, only electricity. They had to walk half a kilometer to a public well for water. Firewood wasn’t available for sale and the parents couldn’t stand in line for brown coal during the day, so they could only bring home some black coal from their work in their briefcases. Gyula attended the boys’ school in Budaörs, along with ‘hard-headed children’, several of whom always wanted to beat him up, because for them he was the city kid. Nevertheless, Gyula loved learning and can still recall his favorite teachers by name. ‘In the summers we wandered around the hills and hung out by the foundations of an old destroyed church, among broken statues of saints. After communism fell, a chapel was erected there in the 1990s, which I visited a few years ago. The wine cellar where we lived is gone—luxury homes were built around there.’

The family moved back to Budapest in early 1956 and lived with relatives close to their former home. Gyula returned for his 8th grade to the Márvány Street primary school shortly before the revolution broke out. His father participated in the demonstrations, but not in the street fight. The children weren’t allowed to leave their home, but Gyula stood in line several times for bread, and often saw Russian armored vehicles drive past pointing guns at them. Barricades were also built at the train station nearby and there were heavy gunfights for days damaging multiple buildings in the neighborhood. Gyula’s parents decided to flee at the end of November, when the Soviet troops oppressed the freedom fight. They knew that his mother would be subject to retaliation, because at her workplace she provided access to freedom fighters to a secret list of previously deported families.

The family travelled by train to the town of Csorna, in the vicinity of the Austrian border. At night, they tried to cross the border on foot, but a civilian stopped them on their way claiming that the Russians had already sealed the border, so they walked back to town. The next day they took a train to another border village where his father saw a priest waiting at the platform. He addressed him in Latin, checking to see if he was a priest indeed. He answered in Latin, so Gyula’s father asked him if it was still possible to sneak through the border. The priest pointed them to a smuggler. That night they tried again. ‘It was very cold and it was difficult to stumble across the deep plowing. Border guards were patrolling ahead of us on the service road, so we had to run through the area in small groups. A barbed wire fence slowed us down, too. Even though its electricity was turned off, it wasn’t easy to grope through in the dark. Every time the border patrol fired rocket flairs, everybody lay down to the ground and waited motionless for a while.’ Two villages became visible in the distance, one with white lighting and another with dim yellow; they chose the former. When they were certain that they were on the Austrian side, their group sang the Hungarian national anthem before it dissolved.

They entered the first farmhouse. ‘It’s a life-long memory. The owners were Hungarians.’ (The easternmost province of Austria, Burgenland was part of the Kingdom of Hungary until the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 and had some Hungarian population). ‘They fed us, gave us shelter and placed us kids into their own beds, that’s how kind these people were,’ he recalled emotionally. The Red Cross registered them and a local family from a nearby village took them in temporarily, in a large room of their inn and restaurant. Gyula’s father, being fluent in German, applied for a job at a West German phone company and was offered a planning engineer’s position. Their other option was America, where a friend of his father’s offered to sponsor them. After a month of hesitation, they chose the latter option; they felt that Germany was just too close to the Soviet Union.

In America

At the end of December 1956, they crossed the Atlantic by air. Gyula remembers that they had to stop mid-way in Iceland to refuel—and that’s where he had his first Coca Cola. They were processed at the Camp Kilmer Military Base. ‘Our sponsor picked us up on the following day. I was amazed by the four-lane highway, given that I had never travelled by car before. Phoenixville was an old steel town in Pennsylvania, where the row-houses were all from the early 1900s; it looked like a movie scene. Our sponsor gave us his attic space to live in temporarily, but we started our own rental two weeks later, because my father quickly got a job.’ He translated German blueprints in the steel works and later passed the bookkeeping exam and worked with inventory. During the 1973 economic crisis he lost his job; he then re-started his business as a watchmaker and continued that along with bookkeeping until his death.

Gyula’s mother never learned English well and was only hired for odd jobs. The family only spoke Hungarian at home. ‘My father was talented at many things, he even won prizes with his paintings and sculptures. They wished to return home for years, but by the time the unexpected regime change took place in Hungary, their kids had grown up and had their own jobs and families—there was no way back.’

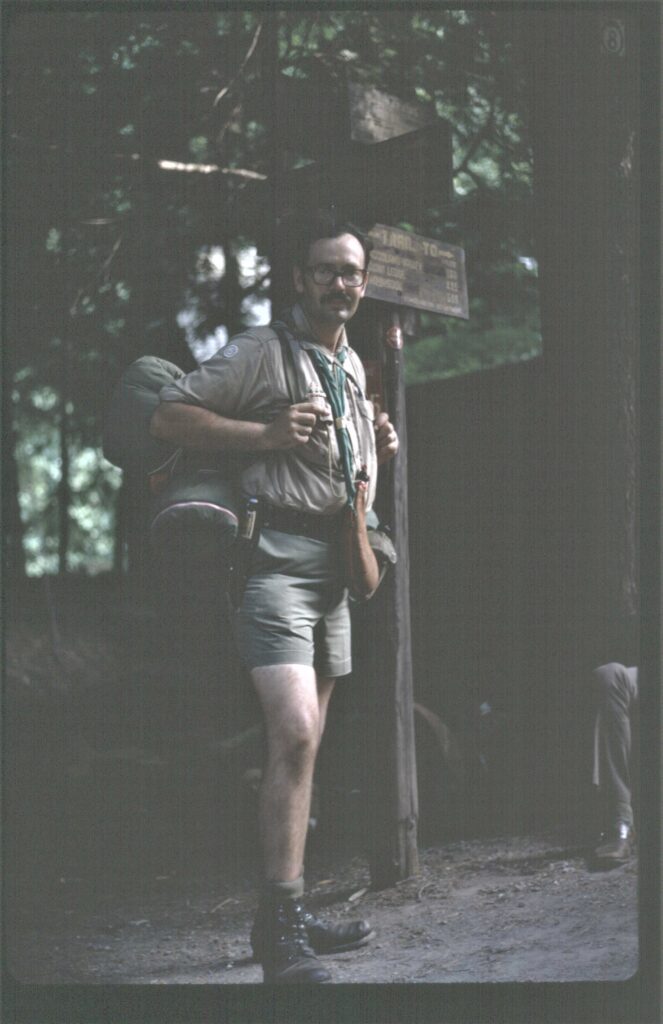

Scouting

Gyula attended high school in Pennsylvania and graduated from Drexel University as a chemical engineer. Shortly after graduating, he started to work at a Hungarian-owned engineering firm in New Jersey. When he moved to New Brunswick for the job, he got involved with the local Hungarian scout troop. Previously, as a high school student, he was strongly influenced by the local Hungarian scout leaders in Pennsylvania. ‘Kati and Laci Pigniczky were able to recruit anyone, they knew how to handle young people. I became the assistant scoutmaster there without leadership training. When I moved to New Brunswick in 1968, Miklós Schlóder, the local scoutmaster—who became my best friend—sent me to the Scoutmaster training camp, where I learned from the best: Chief Scoutmaster Gábor Bodnár, founder of the Association of Hungarian Scouts in Exteris (KMCSSZ), Chairman György Némethy, New York Scoutmaster Viktor Fischer and St Ladislaus Church Pastor Vazul Végvári, OFM, with whom I forged life-long friendships.’

In 1973 Gyula became the assistant Scoutmaster of the New Brunswick Troop. In 1978 he was asked to start managing the local Hungarian school and kindergarten—and he took the call because of the oath made in the scout training camp to do all he can in the interests of Hungarian youth and the preservation of Hungarian heritage.

Hungarian School

From the early 1970s the local Hungarian Catholic and Reformed Churches and the scout troop operated the Hungarian school jointly, and in 1975 they also launched a daily daycare/kindergarten. It was suggested by Gyula’s mother-in-law and was led by his wife Magdi as financial manager and Mrs. Ágnes Balla as daycare supervisor. They started with seven children between the ages of 3–5, including Gyula’s and Magdi’s first son, Gyuszi. While after nineteen yers of service, in 1994 the daycare was discontinued for lack of interest, after a few years of hiatus, Mrs. Balla’s daughter, Enikő and granddaughter, Réka have re-started a private daycare to fill this gap under the name Aprókfalva Hungarian Preschool. The local Hungarian school and scouting were mostly built on the solid foundations laid by these daycare services over the past 50 years.

When at the local scout leaders’ request Gyula took over the school as principal, his and the supporting organizations’ intention was to have a Hungarian Saturday School with no political affiliation based on Christian faith and on the spirit of scouting—learning the Hungarian heritage through experience and games. Gyula completely rearranged the school’s infrastructure, made it part of KMCSSZ, and simplified its administration. The affiliation to the churches waned over time, but the cooperation with the Hungarian scouts continued throughout. Until the early 1990s, they had to collect and design their own teaching materials, because they didn’t want to use the Soviet communist style educational books and materials that were published in Hungary at that time. After the regime change, it was easier to obtain textbooks and other materials from Hungary. As time went on, the initial staff of enthusiastic volunteers became exhausted, which led to a high staff turnover, leaving gaps. The school yearbooks attest that attendance has also fluctuated between 40 and 100, correlating with the political situation in Hungary, the number of new Hungarian immigrants in the area, and the willingness of local families to preserve their children’s Hungarian identity.

Gyula’s 20-year tenure as principal was followed by the younger generation, including Zsolt Balla, who built a parental organization that helped draw families into the school’s life, and later János Gorondi, a very capable organizer and manager. Second and third generation Hungarian youth also started to get engaged with several former students becoming teachers, scout leaders, organizers of cultural events, music and folk dance groups.

‘More and more former students took advantage of their language skills to go to college and accept employment in Hungary…However, we continue seeing a need for nurturing our Hungarian heritage, culture and language, and keep strengthening our relationship with our mother country,’ states an excerpt from the 2003 School Yearbook. Gyula commented: this implied a continuous sacrifice and dedication, which must continue. Without a good command of the Hungarian language, community spirit, responsible and self-sacrificing youth, there will be no one to hand the baton over when the first generation is gone.

‘Our collective survival drove me, as did all the others who worked in the Hungarian community along all these decades’

‘The melting pot mentality can only be avoided by working together and supporting the community. This is why teaching the language and culture to our youth should always be our common goal, instead of leaving it on the shoulders of a few dedicated parents, teachers, and scout leaders that are overburdened and overworked. Family, school, church, scouting, meaning parents, teachers, pastors and youth leaders—their common strength is needed to guarantee children’s Hungarian heritage.’

‘Our collective survival drove me, as did all the others who worked in the Hungarian community along all these decades. Whether you believe it or not, at the age 14 I was already thinking to myself, I’m Hungarian: this is why I became a Hungarian scout, accepted the management of the school, and requested Hungarian citizenship, and this is why I told the audience at both award ceremonies where I was honored: ‘‘I don’t deserve this. I only did my duty.’’ I accepted the awards though, because I hope acceptance serves as an example. Please continue what we started because we don’t want to lose it. My scout oath is for life: as long as I live, I’m a scout leader and I’ll serve my Hungarian heritage until my last breath. This isn’t easy beyond 80, and since my dearest Magdi has left me, but my children and grandchildren keep me going,’ concluded Gyula.

Family

Gyula’s wife Magdi was born in 1947 in Hungary and fled the country with her family after 1956. Gyula met her shortly after arriving in New Brunswick, and in 1969, after his four-month military training—during which he wrote a ten-page letter to her—he proposed to her. Father Vazul married them in 1970, and Laci Hajdú-Nemeth Sr.—Magdi’s first cousin and Gyula’s good friend—helped them with the preparations. The ‘first real Hungarian wedding celebration’ was held at St. Ladislaus School Hall with 200 guests, folk dance group and other performances. Gyula smiled: ‘Magdi was known and loved by everyone. She was the family’s irreplaceable centerpiece, like the heart is to a body. I can thank her for my strengthened faith as well.’

Magdi was also Scoutmaster and a girl scout troop leader for years. With two such active parents, there was no question that their four children—Gyuszi, Laci, Imre and Ildikó—attend Hungarian school and scouting. Gyuszi works as an IT manager and volunteers as a scout parent. His wife, Chilla was also a Scoutmaster and girl scout troop leader and keeps volunteering. They live nearby with their two children: the 16-year-old Livia is a patrol leader and folk dancer; while the 14-year-old Adam is also a scout and a folk dancer. During the Covid pandemic the family lived in Budapest, Hungary for a year with the children attending school, which improved their Hungarian language skills and attachment to Hungary. Both Laci and Imre were Scoutmasters and boy scout troop leaders for several years. Laci lives in Princeton and isn’t an active scout now, while Imre is a marketing researcher and is very active at the leadership of KCSMSZ. He lives in Syracuse, New York with his second wife. Gyula’s and Magdi’s only daughter Ildikó spent more than eight years in Hungary after graduation. She’s an economist, works at a French company and lives with her husband and two little girls—two-and-a-half-year-old Cilike and six-month-old Evelin—in the family home next door to Gyula.

Church

‘Family, school, church, scouting. The combination of these four elements is the only way the Hungarian diaspora can survive in North America. Despite the lack of a perceivable enemy today, we give up ourselves,’ Gyula said sadly. He was the Parish Council President at both occasions when the community had to struggle for keeping their Hungarian priest and the church doors open. After the regime change in 1989–90, the Hungarian branch of the Franciscan order scaled back its missionary presence in the U.S., offering priests the opportunity to return to Hungary or to stay and be absorbed by the local dioceses. Father Máté Kiss chose to stay and serve in New Brunswick, but after some time his bishop decided to reassign him elsewhere, meaning that St. Ladislaus parish would have been left without a Hungarian priest. ‘At our request, Father Capistran Polgar, OFM was sent here. He grew up in New Brunswick, attended the St. Ladislaus School, but his spoken Hungarian language skills had waned over the decades he served in English speaking parishes. He could keep the mass in Hungarian but said his homilies in English. Even so, he was an exceptional pastor.’

The most recent occasion to defend the church occurred when approximately 10 years ago parishes were consolidated across the U.S., which negatively impacted several Hungarian parishes, e.g. those in New York City and Cleveland, OH besides theirs in New Brunswick. ‘Laci Hajdú-Németh and I went to the bishop’s deanery meetings and spoke up, but they didn’t appreciate us being there at all. We appealed the bishop’s decision, first to the papal congregation and then to the papal higher legal court but they also dismissed our appeals. These procedures caused me great disillusionment and cost us a lot of time, effort and some 10–15 thousand dollars…’

‘Family, school, church, scouting. The combination of these four elements is the only way the Hungarian diaspora can survive in North America’

He confessed: at a personal level, he had a long road to his faith. He always believed in God, went to church, raised his kids in a Catholic spirit and within the church community, but he was not a ‘man of prayer’. Over time, faith became of greater importance to him, especially when he had to pass it onto his kids and realized it was fading from scouting and school life as less and less parents were taking their children to church. At this point, a long silence followed, and I was about to say good-bye when Gyula’s eyes suddenly got teary.

‘My faith has deepened since the death of my wife, this lovely woman I loved so much. Her life completely mirrors her last day: at 8 am someone called her for help to get their medication order sorted out. She placed a few calls and fixed it in 45 minutes. Then she left for the hairdresser, because we were expecting guests in the afternoon. She came back with a pretty hairdo and even had her car washed and vacuumed with which she went grocery shopping for dinner. Back home, she immediately started cooking the family’s favorite chicken soup, which we call mom’s soup. Around 5 pm she called me: ‘‘Gyuszi, come in, the soup is done!’’ A few minutes later I heard a loud crash from the kitchen. She laid on the floor unconsciously. It hit her like a bolt of lightning… We both had health issues and were under physician’s care. I had a heart problem, even had a pacemaker implanted, that’s why I thought, I’ll be gone first, she was only 75 and very active… There are so many things I wanted to share with her… It wasn’t long ago that we moved into the newly refurbished house … She didn’t get to see her youngest grandchild or be at Imre’s wedding… It’s very difficult. But my faith has grown since, because even though this is a great tragedy and devastating loss, God was merciful to her: she was taken by the angels this quickly. I couldn’t have asked for more on her behalf.’

Read more Diaspora interviews: