I met Kinga at events organized by the Saint Stephen’s church community in New York. I’ve only recently learned from her that for the past ten years she’s been working to carry on the professional legacy of Lajos Szamosi, a Hungarian singing teacher unjustly neglected in his homeland, and to make his valuable teaching approach—based on free singing and not fitting into the mainstream—known to the singing and vocal pedagogy community back in Hungary.

***

Is the love of music and singing a family legacy?

My parents were not musicians, ‘just’ simple people who loved music, but were very supportive of their children’s musical education. My grandfather was a choir singer in the local church, and my grandmother also had a beautiful voice. So no one in the family was a professional musician, but for me, it was very clear from early childhood that I’d pursue a musical career. I grew up in Budakeszi—a small town close to Budapest—and after finishing kindergarten, I enrolled in the special music class of the local elementary school, where Kati Béres was my first music teacher. Just as I finished elementary school, a music class was launched at the Táncsics Mihály High School in Budapest, where Géza Klembala became my music teacher. From there, I was immediately admitted to the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music, majoring in Kodály concept and choral conducting, which qualifies me to be a music teacher in any kind of school and to lead any kind of choir.

However, since singing has always been a great desire of mine, I wanted to engage in that as well. When I was planning to write my thesis about singing pedagogy at the Academy of Music—a topic I was always drawn to—I came across the book The Path of Free Singing by Lajos Szamosi, which had just been published. I felt as though fate had sent to me this man: every thought he expressed about singing matched exactly what I had thought myself. That’s when I learned that Szamosi’s two children live and teach in Vienna, Austria, and I thought that someday it’d be wonderful to seek them out and learn from them directly…A few years later, this happened—again, quite fatefully. After graduating, I applied for a special postgraduate program in the Netherlands. After a while, I decided to move to The Hague, as I was very drawn to the elegant, French-style royal city. A friend told me he knew a singing teacher there who was renting out rooms. When I met that lady, I felt from the very first moment that I had something important to do with her. It turned out that Heent Prins had been one of Lajos Szamosi’s students…

Before you continue your story, please briefly introduce Lajos Szamosi to us.

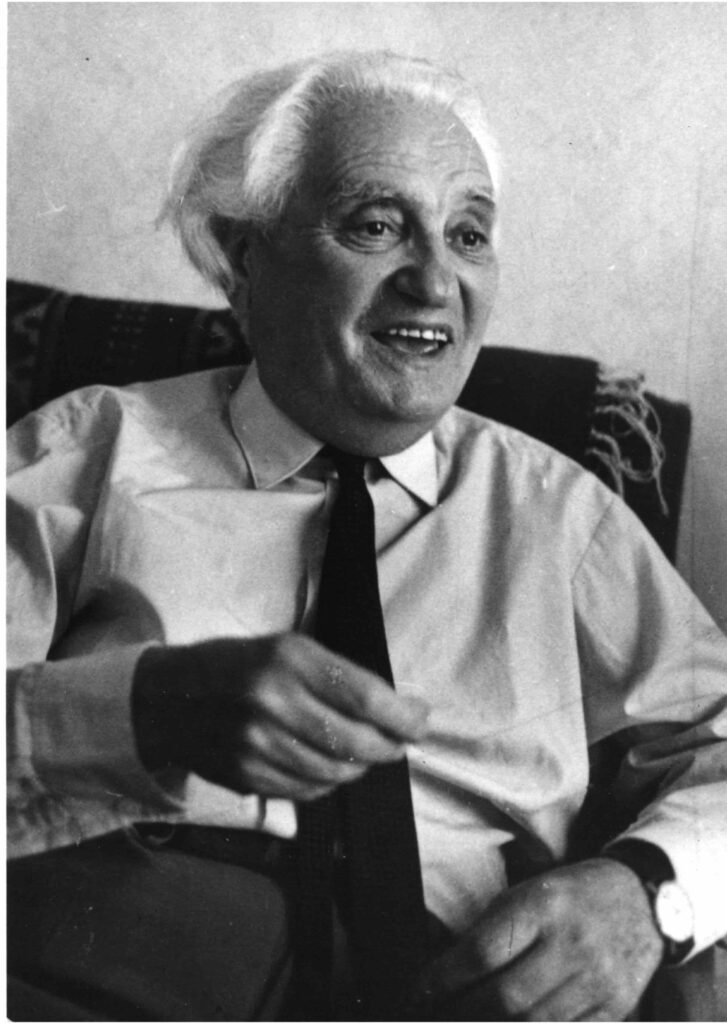

It would be worth writing a whole article—or even an entire book—about his life and work, because sadly, he is barely known in Hungary, while practically everyone knows Zoltán Kodály despite the fact that Lajos Szamosi also developed a complex pedagogical system during his lifetime. Szamosi’s ideal was the old Italian singing schools; he aimed to follow the traditional aesthetic they represented. Driven by insatiable curiosity and a restless thirst for knowledge, he studied these traditions in a self-taught manner and sought a solution to his own ‘vocal fault’, which the most renowned Hungarian and international voice teachers of the time were unable—and unwilling—to take seriously enough to help resolve. Nevertheless, he traveled through half of Europe to understand his problem from medical, special education, vocal pedagogy, and even psychological perspectives. In the end, not only did he resolve it—and helped many other singers—but he also developed an entirely new way of singing teaching, the main ideas of which he summarized in the aforementioned book The Path of Free Singing.

However, in 1944, due to his Jewish background, he was forced to leave Hungary. He ended up in Italy, where he rented a studio in one of Rome’s musician districts (Prati), and took on students—mostly Italian singers—with whom he achieved spectacular results. Within a few months, he was already organizing house concerts, and his name became increasingly known. The press also started to take notice, and articles began appearing about him in various newspapers. They realized he knew something that other singing teachers didn’t. They claimed he had ‘discovered the lost secret of bel canto’. He was offered a teaching position at the prestigious Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, but accepting it would have required renouncing his Hungarian citizenship and taking up Italian nationality. So, he was practically on the brink of international fame when he had to choose between his family (and homeland) and his professional advancement.

Since his children and grandson had remained in Budapest, and he had also been offered a good position there, he returned home. Unfortunately, not only did he not receive the promised position, but professional jealousy prevented him from advancing. Due to the continued neglect and attacks, in 1956, at the age of 61, he emigrated to Austria. After successfully rehabilitating the voices of two actors from Vienna’s Burgtheater, he was appointed as a teacher at the Vienna Academy of Music. After retiring, he continued teaching private students. From among his advanced students, he formed a vocal ensemble called Collegium Canticorum, with which he organized Austrian and international tours. The Dutch and Swedish press published articles about him. One of his students performed as Oscar with Plácido Domingo and as Musetta with Luciano Pavarotti. He taught until the last day of his life. His work was assisted by his son Edvin and daughter Hedda, who, after their father’s death in 1977, continued his private teaching work. Due to the enormous workload, the comprehensive book he planned was never completed.

What is the essence of his methodology, and what drew you to it?

In today’s mainstream vocal education, they essentially try to impose some sort of technique on each student, while Szamosi wanted everyone to find their own, completely unique voice. His goal was not to mass-produce singers on an assembly line, but to draw out what’s most individual in each person. This isn’t easy because the teacher needs to have a huge toolbox and a deep empathy to understand where the students currently are and where they want to go. It’s a highly personalized form of work, and it’s like a kind of investigation—that’s why it’s so exciting. It requires a certain maturity, self-awareness, and curiosity on the part of the students as well, because the singing teacher can only guide and assist them to find the right direction, but cannot walk the path for them. In addition, every person carries a backpack full of troubles, sorrows, traumas, etc., all of which get in the way of singing and expression—in breathing, as in life—and this pedagogy can help to loosen them up a bit. However, what gives great freedom can also provoke fear. So free singing also requires courage. Since I’ve always loved this kind of freedom, I felt from the very first moment that this approach was made for me.

Let’s return to the years in The Hague…What drew you there so strongly?

In the early 90s, the Netherlands felt to me as if I had landed on another planet after communist Hungary. Dutch people were very open and culturally rich; many nationalities lived there, including ones I had never heard of. When I went to the market, I was shocked to realize that I didn’t know most of the fruit and vegetables there. I began to understand that the world is much bigger and more interesting than the one I had known until then. At the same time, I was completely captivated by Heent’s personality—she was not only one of Szamosi’s students, but also a follower of anthroposophy, founded by Rudolf Steiner. She was deeply drawn to the Waldorf schools’ human-centered, holistic approach to teaching and child rearing. It was very nice to be around her. She opened up a world for me that I had always deeply longed for—therefore, I consider her my second mother. When I met her, I had the feeling of arrival. She first heard about Lajos Szamosi in a radio program in the 60s, and read an article about him in a local newspaper—these inspired her to decide to study singing with him, even though her first son had just been born at the time. She kept going to Vienna to study until Szamosi’s death.

‘The ultimate goal is to create a teacher education program so that those who are really interested in this approach can carry it forward’

How long did you stay in the Netherlands? Why did you return to Budapest?

I had a lot of impressions to absorb and a great deal to learn and reconsider in a short time. After completing the postgraduate program, I applied to the Royal Conservatory of The Hague for the vocal program and was accepted, but I suddenly felt an intense homesickness. I began to feel emotionally unstable; I felt I could no longer stay in the Netherlands. After returning home, Heent traveled to Vienna and introduced me to Edvin and Hedda Szamosi. That was another fantastic moment for me—just five years earlier, I had only dreamed this might happen. From that moment on, my fate was practically sealed. I taught in Budapest but went to Vienna two or three times a year; I sang at a small opera company there, then began giving concerts, and also went to Edvin for singing lessons. I’m very grateful to fate that he was able to teach me for ten years, while he was still healthy. They treated me as family and welcomed me among them—just as Heent and her family had earlier. They treated all their students like this; that’s why such a strong singing community could form around them. Meanwhile, at Deborah Carmichael’s invitation, Edvin traveled to New York two or three times a year, where he also built a class and a community. I met Deborah in Vienna; she also has her own story of how she met the Szamosi family. In 2010, Edvin officially authorized only Deborah and me among all his students to carry on the Libero Canto approach.

How surprising was this for you? Is that why you moved to New York?

I always felt that he was continuously guiding the two of us in such a way that we’d have to work together closely, having joint concerts and workshops. It was very important to him that we understand each other very well and could always rely on one another. In 2014, I moved to New York because I realized that the two of us needed to be in the same place in order for our plans—to establish a singing studio—to actually become a reality. There were 20–30 people here who were already part of the Libero Canto group when I arrived. In addition, Deborah’s family is able and willing to financially support the singing studio. Since I moved here, we’ve held countless workshops, organized concerts, taught students, and arranged ongoing education events for singing teachers and advanced students. We are trying to expand the singers’ and singing teachers’ community as much as possible—that is, to spread the ‘Libero Canto seeds’. The ultimate goal is to create a teacher education program so that those who are really interested in this approach can carry it forward. In New York, we launched the first official teacher education program in 2020, which consists of two years of a foundation program (the basics), followed by two years of an apprentice program, and then final exams.

Did you return to Hungary with this goal as well?

Yes. Last year, I felt that the time had come and that it was necessary, because we won’t live forever. If I start building the community now, we could have teachers in ten years’ time. Thus, in January 2024, I gave a presentation about the ‘Path to Free Singing’ pedagogy at the House of Music Hungary, this year I continued the series of lectures at the House of Dialogue and at two music schools in Budapest. This summer, from 28 June to 6 July, I’ll have a special workshop, working with the basic song material of the Libero Canto approach. Earlier, we launched an international research project to find the original versions of songs from the popular Parisotti singing books. We will perform about 20 of those songs and arias at this summer workshop, accompanied by period baroque instruments. We will have two concerts with the Hungarian Simplicissimus Ensemble, on 5 July in Budapest, in the auditorium of the Szabolcsi Bence Music School, and on 6 July in the beautiful Havas Boldogasszony Catholic Church in Zebegény.

How easy or difficult do you think it will be to establish this methodology in Hungary?

My primary goal is to make people aware of the existence of this singing pedagogy. Since the political situation has changed, we don’t face the same obstacles as Szamosi did, but not surprisingly, no one supports us either. The Libero Canto approach presents a completely different paradigm that hasn’t entered the mainstream, because traditional singing schools have a very tight pace of teaching, there are tough exams and performances, which we don’t have because we don’t see the point, as everyone develops at a different pace. Thus, we couldn’t fit into the existing traditional schools; for us, the alternative path is the only option: to introduce this vocal pedagogy to as many people as possible, and to reach out to those singers and singing teachers who can’t find their place in the mainstream.

Do you think there is an existing need for this?

Definitely. There are many people who find traditional singing teaching difficult because they develop differently or struggle with problems that they can’t deal with in music schools and conservatories due to the time constraints of the constant pressure to perform. This was exactly my main problem at the time. Last year, when I worked with choir singers, many of them showed interest. With this year’s course, I’d like to reach those who have already studied singing, but are still searching for alternative paths. I hope that those searching for a different path and we, who offer a new approach, can ultimately find each other. We can’t recreate the cultural milieu that existed in Szamosi’s time, but we can at least ensure the survival of his approach. He was a brilliant Hungarian vocal teacher who loved the Hungary that existed before World War II—that incredibly rich Jewish cultural and intellectual circle of acquaintances and friends, where scientists, musicologists, artists, psychologists, singers, pianists, etc., met regularly and supported each other. When Edvin told me about this, I could feel how truly amazing, special, and mutually enriching that community must have been. Perhaps that’s part of the reason his father returned home from Italy: he believed that the old world could be recreated—but in those five years, the country had changed so much that this dream or desire became completely impossible… Since then, those people have literally disappeared, emigrated, or passed away, and their descendants are already different people, because we live in a different world now. We can only think of it with nostalgia but can’t bring it back. Even Edvin and Hedda could only maintain a very small community; they kept the memories, this special atmosphere, and the fantastic heritage of their father in their own home. When Deborah met Edvin, she recognized almost immediately that this was a brilliant approach to singing pedagogy. It’s thanks to her that this small group of singers and singing teachers still exists, otherwise this brilliant pedagogy would have disappeared from the world…

‘I’d be willing to do anything because choral singing is extremely enjoyable and, moreover, builds community’

How did you get involved with the Saint Stephen’s Catholic community?

Margaret Arnóczy invited me into this community during the COVID pandemic, when the world came to a halt. The singing school couldn’t organize performances, events, conferences, and couldn’t travel either. At the same time, the local Hungarian communities opened up to me, which I hadn’t had time for—or interest in—before. Since then, I’ve developed a very close friendship with this community, especially with Róbert Winer, the president of the Lay Committee. I’m not a devout Catholic, but at his invitation—when there is an important official guest, a festive or funeral mass, or if the cultural standard of an event needs to be elevated—I gladly come to sing whenever I can, because to me, this is service. There were times when they hosted us; we held two concerts in their church. We also offered our cooperation to the Hungarian Consulate General in New York, and they gladly accepted it during the pandemic, because at that time, they too couldn’t invite artists from elsewhere. Since then, however, they haven’t invited us again, though I’d very much like to continue serving the local Hungarian community. I’d love to work with the Hungarian School in New York and the local scouts as well…

I remember you having a charity concert at the Hungarian House in New York. What’s the story behind? Any plans for continuation?

The first performance of our Ágról Ágra program was the charity concert we had at the Hungarian House in New York in 2022, and the proceeds were donated to the local Hungarian Scout troop. There is a beautiful story behind the birth and development of this program. Deborah’s mother loved music very much, and we always celebrated her birthday with a small house concert. When once I sang a Hungarian folk song for her, she liked it so much that she asked us to make a full-length program out of it. She envisioned a program of only solo Hungarian folk songs, but I developed it further. I first selected the folk songs, then added a couple of pieces by Béla Bartók, and finally approached four composers—an Argentine, a Korean, a Portuguese, and an American—to each arrange a different Hungarian folk song. The program became quite unique: it includes traditional Hungarian folk songs in their original form, pieces by Bartók, and contemporary folk-song arrangements. Many people around here love and study Hungarian folk music. Bartók’s music is highly regarded by both jazz and young musicians here in America. After the concert, we did some smaller tours. The program can be revived at any time, and there are even plans to perform it in Hungary at some point.

Do you have any other plans?

My life is now fully occupied with teaching, developing, and promoting the Libero Canto approach, and I am hoping to start a teacher education program in Hungary as well. In addition, I recently conducted a mixed chorus on two occasions, so conducting has returned to my life, and I’d like to have my own choir. If someone in the Hungarian community is interested, I’d be very happy to offer to start singing with Hungarian children or even adults living here. I can also imagine working project-style—either a group of children or adults would come to me, or I could travel to them occasionally for a weekend, and I’d work with them. Thus, it wouldn’t have to be just children from New York—it could be those from farther away too, from Long Island or nearby states. I’d be willing to do anything because choral singing is extremely enjoyable and, moreover, builds community.

Read more Diaspora interviews: