This is an abridged version of the original interview first published in Magyar Nemzet on 19 October 2023.

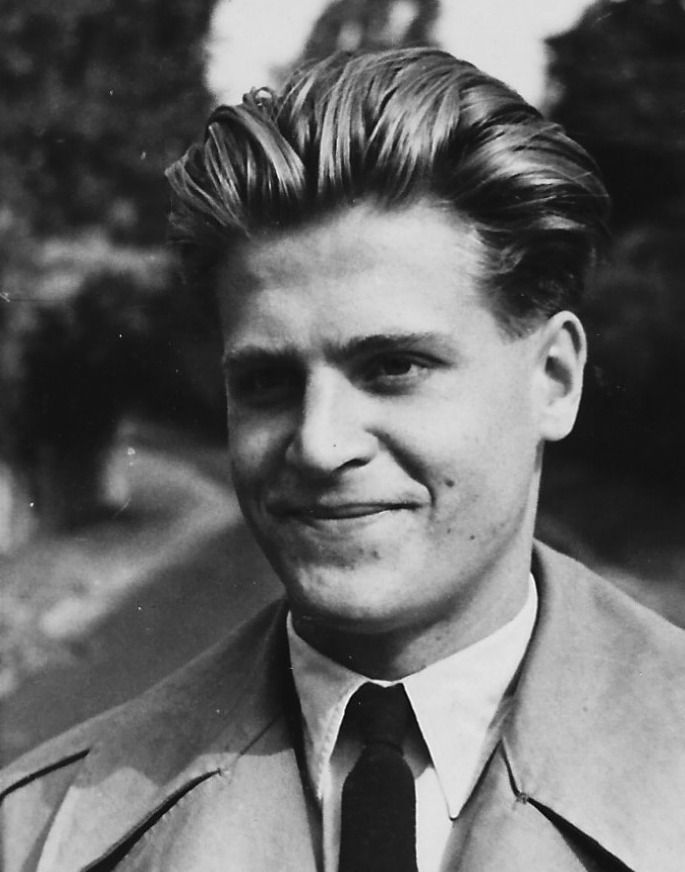

I first heard about Balázs Somogyi from his sister, Mária, and later, Kálmán Magyar introduced me to him. When I visited Balázs at the Hungarian Day in Wallingford in September 2023, I briefly inquired about the circumstances of his family’s immigration and, at length, about his diverse service to the Hungarian communities in New York and later in Connecticut, for which he was awarded the Cross of Merit of Hungary in 2016.

***

Balázs Somogyi was born in 1938 in Győr, Hungary. His paternal grandfather was a Reformed minister, while his father, Pál Bertalan Somogyi, was a military doctor who served in the Hungarian Army during World War II, including the Battle of Stalingrad. His mother, Mária Csermez, originally came from a family of landowners in Upper Hungary (currently Slovakia), later settling near Győr. During World War II, Balázs spent time at his mother’s family estate in Győr, but as the Soviet troops advanced, the family fled to Germany. While working as an orthopedic surgeon there, his father struggled with such intense homesickness that the family returned to Hungary after the war, where the shortage of professionals allowed him to continue his work despite his family background, which put him at a disadvantage under Communist rule.

Balázs had just started his medical studies when the 1956 Revolution broke out. During the freedom fight, he worked alongside his father in the Szabolcs Street hospital, treating primarily gunshot wounds, both Hungarians and Russians. The visual memories left a lasting impression on him: he still clearly remembers certain agonizing faces, such as when they had to amputate the leg of a 16-year-old girl or when they buried the girl next door in the backyard. After the revolution and freedom fight was crushed, the family decided to flee. By early 1957, they were living in Vancouver, Canada, where his father was initially promised a job at the local hospital. Balázs and his younger brother had to work in the woodworking industry, his mother sewed tents, but his father remained unemployed. Eventually, through medical connections, they managed to secure a medical position for his father in New York, so the entire family moved there. They soon became active members of the local Hungarian community, centered around the now-defunct St. Imre Club, where they regularly organized balls, sports events, and scout meetings. It was there that Balázs met his future wife, the visual artist Csilla, daughter of the renowned Transylvanian cameraman Árpád Makay, who, after a four-year detour in Switzerland following World War II, arrived in America with his family in 1952. They married in 1964, and after moving to Connecticut, they had three daughters. They have one grandson, Kristóf. Balázs worked as an orthopedic surgeon until the age of 82. For decades, he and Csilla have been active members of the local Hungarian community, and they continue to be so. In addition to leading the New York-based Hungária Dance Group for two decades, they are still active members of the Hungarian Communion of Friends (Magyar Baráti Közösség, MBK), which organizes the annual ITT-OTT Conferences at Lake Hope, Ohio. Balázs is the founding president of the Connecticut Hungarian Cultural Society and the cultural program coordinator of the Hungarian House in Wallingford, Connecticut. They have also organized numerous cultural events in their own home.

You said that in the 50s, you were schizophrenic and felt constant tension, yet you didn’t become mentally ill. Generally, those who speak about this period don’t usually emphasize this state of mind, though it would be very important since nowadays being mentally ill has almost become a trend…

Surviving with a sound mind is obviously an individual ability, but the support and overall atmosphere in the family certainly contributed to it. One of my grandfathers was a Reformed pastor, and the other was a county chief magistrate, so, from the Communist regime’s point of view, we were a ‘reactionary’ family who didn’t accept the people’s democracy. Our family certainly helped us develop a healthy outlook on life. We weren’t spoiled; we got used to difficulties, and we even took them for granted. Such behavior was necessary because the environment in those days could be inhumane. The Communists’ ideological demands made our lives harder. Unfortunately, I’ve recently started noticing the manifestations of such ideology even in the United States, but that’s a topic for another discussion… At home, we constantly received the ‘counter medicine’: when we returned home from school and reported what had happened there, my parents would tell us: ‘My dear son, that’s not exactly how it is; in fact, it’s completely different…’ Thus, we developed an attitude that made the manifestations of the Communist regime seem almost negative or non-existent. Additionally, in our family, there was a healthy attitude towards life, setting an example for us to follow, showing that we shouldn’t always expect the worst; instead, we should see that there is a way out. At the same time, I met many people after 1956 who, despite having gone through similar experiences, reacted quite differently later on. Based on my memories, at least half of them survived this period intact, while the other half had problems. I met people who suffered from almost unbearable homesickness; others smoked 40 cigarettes a day, and yet another constantly longed for his mother and, therefore, returned to Hungary.

‘Surviving with a sound mind is obviously an individual ability, but the support and overall atmosphere in the family certainly contributed to it’

Your family members not only remained mentally intact but also turned their coping strategies into active energy. You, your wife, and your sister continue to make significant contributions to the Hungarian community to this day. Could this lifelong volunteering, which characterizes your family even after 80, be related to the experiences you had as a child?

Certainly, though interestingly, until I was 18, I was a very introverted person; I didn’t really like communicating with others, appearing in front of an audience, or even speaking up. This changed when Gábor Csordás, a Reformed pastor, once told me that I had to be the master of ceremony at the Protestant Ball. I was in my 20s then, and since then, I’ve had no problem talking to people. This skill must have been deep down in me, but it only came out then. I’m grateful to very few pastors, but to him, I definitely am.

You and your brother decided to leave the country after the revolution was crushed, regardless of whether the rest of the family followed you and despite the fact that your father had previously returned from post-war Germany because of his homesickness…

I’m a little ashamed of myself because, in a way, we forced our parents to choose between us and Hungary. At the same time, it was their decision as well. I know they contemplated for long nights before making the final decision: the family should stay together. I also know that both of them, especially my father, lost a lot by leaving Hungary. He was able to be a very successful doctor and a respected social figure back home despite his family background; however, in America, he had to start all over again. I felt strong guilt because of this, but later, I realized that he wasn’t an unhappy person in the end. Indeed, in Germany, his homesickness was so intense that it actually made him mentally ill; that’s why we returned to Hungary, but he somehow didn’t bring his homesickness here, to North America, which I still can’t explain. He never said, for example, that he’d like to return home. He accepted the new life here immediately, which was very bitter for him, especially in the beginning. Even though he lost everything and had to start over multiple times, he persevered and kept trying. This was a big lesson for me: if something doesn’t work out the first time, try again. I’ve been following this principle since then, and I’ve benefited from it many times. Even during the one-and-a-half-year stint in Canada… We glimpsed the life of ordinary people and realized that some must do the same thing for their entire lives: go to a company and work there for eight hours a day, with no other option. I quickly realized that I didn’t want to live like that. Luckily, I didn’t have to. Canada was a good lesson. It also changed the way we saw the Hungarian community in the West.

What do you mean by that?

In Hungary, people don’t really have a comprehensive understanding of the Hungarian community living in the West. In Canada, we experienced a very wide range of connections. When we arrived in Vancouver, there was a Hungarian house where we occasionally went. Some people, despite sitting or standing only a few meters away from each other in the same room, chose not to talk to each other and continued this habit for the rest of their lives. They probably didn’t even remember what the original cause of their hatred was; they only knew they ‘had to’ hate the other person. This was very sad, and I still occasionally experience it nowadays, although it’s much less of a dominant feature than it was back then. I understand those people who said they wouldn’t go to places filled only with such hatred. We had a similar experience with fierce disagreements among Hungarian communities in the U.S., but since then, thank God, they have softened greatly. Perhaps because those who really believed in this behavior have already passed away. I’m not saying that in 2023 this phenomenon no longer exists, whether in Canada or the U.S., but it’s much more bearable now.

You said that the belief that life would be different in America kept your family’s spirits up while you were in Canada. Did it turn out to be true?

Yes. This became a family saying; we used it to encourage each other. But it wasn’t so easy to come to America either because my father was accused of being a Communist party secretary. In Vancouver, they investigated his life in Hungary, and finally, it was verified that he wasn’t antisemitic or Communist. Yet, when he finally received an invitation from a hospital in New York through his medical connections, and we submitted our application to the U.S. consulate, we got an answer a week later: they couldn’t let us into the country. Fortunately, we had a friend who could access the files, and we discovered that there was another doctor with the same name who was a committed Communist party secretary. Eventually, the American authorities recognized the mistake and gave us permission to immigrate. This meant a great deal to us: I could start studying again, develop professionally, and work; in this sense, it brought only good things to me. In America, at that time, everything depended on how committed a person was. Even though I came here as a Hungarian, and my accent still made it clear after many years that I wasn’t a child of this country, I didn’t encounter any obstacles in my professional life.

Not only did your professional dreams come true, but also your personal ones. You planned to have a Hungarian wife. Why was this important?

In those times, if a Hungarian man married an American woman, in most cases, the marriage didn’t work out. However, I was in a lucky situation because, besides meeting Csilla, a true Hungarian community developed over the years around the Hungária Dance Group; many of its members married one another. At least 90 per cent of these marriages are still working; only death will put an end to them. They were and remain a very important part of my life because I found myself in an environment where, both as a person and a folk dancer, I was able to stay positive. I can only speak positively about them. We spent our youth in a positive community.

You met Csilla at the St. Imre Club, and you’ve been a great ‘team’ ever since. What motivated you beyond the good communal experiences?

The St. Imre Club was a central gathering place for the Hungarian community in New York, where several events, including scouting, sports activities, and balls, took place—this is where I encountered the concept of the Pöttyös Ball, which I had never heard of before. Our involvement in community work stemmed from the Hungária Dance Group, where we recognized that it’s really worth working in a community where we can count on each other and create something together. That’s where it all started, but I can’t explain what exactly triggered this enthusiasm in us beyond the fact that we always felt it was essential to preserve the traditions of the Hungarian community living here and to keep things running along Hungarian lines. My daughters are always accusing me of having big ideas, which my wife has to make happen; in other words, I force my ideas on Csilla and expect her to take part in them. The truth is, Csilla sometimes gets tired, but she doesn’t mind that we’re still doing something. Currently, we’re trying to save two initiatives that were on the verge of being stopped. At this stage of my life, my task should be to prevent the remaining Hungarian organizations from collapsing or disappearing…

What are these two initiatives?

One is the 70-year-old Pannonia Club in Fairfield, Connecticut, whose leadership included people my parents knew from Hungary. The club stopped organizing its balls for a while, but now it looks like the financial resources will allow us to carry on. We’re currently working on this. From the outside, it may not seem significant, but it’s an important factor for the Hungarian community living here. By keeping the ball, we keep Hungarian traditions alive: the ball will be conducted in Hungarian, a Hungarian band will play music, and children of Hungarian parents will be awarded scholarships.

‘By keeping the ball, we keep Hungarian traditions alive’

The other initiative is actually an ongoing matter. Leaving New York, we got involved in Hungarian life here in Connecticut as well. We had to face the same difficulties at the Wallingford Hungarian House that I had already mentioned: initially, we only heard about people shouting at each other in various ways, who clearly hated each other, and they made it obvious to the public. After we joined the Wallingford team, other people started coming here who didn’t spend most of their time shouting at each other. Since then, work has been done here in a way that wasn’t happening before. In 2006 it was suggested that we should sell it, but many said their children needed to preserve Hungarian traditions. At that point, Hungarian life here revived again, and although many people drifted away again since then, the future of the Hungarian House seems solid and secure at this moment. Moreover, we got tax-exempt status and received unexpected support. As a member of the board, I took on the role of the cultural officer, and I do it with great joy.

What cultural events are held at the Hungarian House?

Primarily, it’s about preserving our traditions. For example, we are restarting Hungarian language lessons for those who want to learn Hungarian or refine their language skills. Of course, we celebrate the major national holidays there, and we hold every Hungarian event that we have the opportunity to. Right now, for instance, a female vocal group called Pacsirta will unexpectedly perform for us. They play pop music, which doesn’t mean much to me, but many enjoy it. At the end of October, our old friend, Judit Havas, will come to recite Sándor Kányádi’s monumental poem ‘Halottak napja Bécsben’. Kányádi also visited us and stayed with us in the past. He was a very good friend of mine; I also visited him when I was in Hungary.

Many cultural events are hosted at your own house. Why?

A lot of effort, both individual and family work, has been invested in our house because certain programs can’t be presented properly in the Hungarian House, as the general public doesn’t necessarily want or tolerate everything. Therefore, if it’s something that draws a narrower interest, we host it at our house, and if it’s something that suits the public taste and attracts a larger crowd, then we organize it at the Hungarian House. For example, Pacsirta is a great fit for the Hungarian House. A book presentation is probably more suitable for our own house. In this sense, these two venues complement each other well.

You were president of the MBK twice and a regular participant of the ITT-OTT Conferences at Lake Hope, Ohio. Their calendar states: ‘A non-denominational Hungarian religious society registered in Oregon.’ Is this still the case?

The first ITT-OTT meeting took place in 1968. Csilla went there first in the early 70s with our children, and when she came back explaining that it was a very good initiative, I started attending as well. We were there this year, too, unveiling a memorial plaque in honor of Hungarian miners buried in the nearby cemetery called Congo, which also had its significance. There will be another ITT-OTT next year, but the question has arisen whether it will be the last one. That’s the next initiative that needs to be saved. However, there is also a positive development: some young parents with small children have appeared who want it to continue.

‘Hungarian life here revived again, and although many people drifted away…since then, the future of the Hungarian House seems solid’

As for the quoted text, the idea was initially that we should live our Hungarian life in a religious manner, which I had no objection to. Although this text remains in the MBK’s constitution, the religious aspect is only evident in the presence of a mass or church service at the beginning, led by Hungarian American pastors. However, it was never necessary for someone to show a specific religious belief or affiliation in order to participate. Yet there was a time when some people portrayed us as a crazy group who sacrificed a white horse by the lakeshore… Of course, this never happened; there was never any need or direction for it, yet the papers published it.

Our original goal was to preserve Hungarian traditions. Initially, we invited many Hungarian politicians and artists who had been silenced in Hungary, allowing them to freely express their opinions at Lake Hope. For instance, in 1986 István Csurka, Sándor Csoóri, Gábor Demszky, and Imre Mécs appeared there at the same time. The hatred between them was palpable, but we managed to survive that as well. I’m sure at that time there were Communist spies among us who were taking notes of and reporting everything. Later, I even got a hold of a document that detailed what they wrote about me. But who cares about it now?

In addition to political invitations, literature was the strong point of these conferences. How did the original aim change after the 1989–90 regime change in Hungary?

Preserving Hungarian literature was indeed one of our main goals. Gyula Gombos, a close friend and a dedicated Hungarian, initially visited Protestant groups operating in America, primarily Reformed, and wrote and spoke about them. Another key figure was György Faludy, who visited us many times and also attended the ITT-OTT Conferences. His intellect, education, and talent had a huge impact on us. I’m currently studying his poems; I think it’s important to engage with them. After the regime change, the MBK membership became a little uncertain about its goals, but we regained our strength when we realized that our task was no longer to give a voice to critics of the Communist regime but to demonstrate what was necessary to preserve the Hungarian identity. This became our most important aspect, and literature continued to play a central role in it. However, it’s true that in the past, the event lasted for a week, with attendance exceeding 200, whereas now it’s only four days, and we typically have 60–80 people, with a maximum of 100. This year, only 45 attended. Occasionally, there are clashes with other programs, like scout or folk dance camps; we tried to solve this, but unfortunately, we couldn’t always succeed.

You’ve been the president of the Hungarian Cultural Society of Connecticut (HCSC) since its inception. Do you still actively run it?

We started the HCSC at the end of the 60s in Connecticut. Our goal was also to preserve and, if necessary, adapt Hungarian traditions to local conditions. Every year, we organized a major gala ball, and the proceeds supported Hungarian communities in the Carpathian Basin, helping them access information when it was most needed. For example, we installed antennas in Transylvania (Romania), Vojvodina (Serbia), and Upperlands (Slovakia). We also operated a scholarship system, supporting 100 students in five Hungarian-language schools and colleges beyond Hungary’s borders. We hosted many important authors at our gala ball events, including András Sütő, István Soós, Sándor Csoóri, and Sándor Kányádi, who attended multiple times, as well as literary historian András Görömbei. The gala ball worked very well financially and enabled us to continue our work. We didn’t just host events but also supported every Hungarian event we considered high quality. Recently, it seemed as though we’d have to stop, but we received unexpected financial support two weeks ago—completely anonymously but entirely legitimately—that allows us to continue our work. I don’t have specific plans yet, but I’m already working on it enthusiastically.

Another revival task suitable for a doctor. But aren’t your daughters right: isn’t it too exhausting? Or the opposite: does it energize you?

There was a time when I thought I’d collapse during a patient examination, bidding farewell to life. That was my idea of how I’d die. I practiced until I was 82, but death still wouldn’t come. So, I have to keep myself occupied, and it looks like there will be plenty of opportunities for that in the future…

Related articles: