Péter Forgách fled Hungary with his parents in 1956 at the age of 10, and in a way he owes this decision to a poor math grade. Influenced by Hungarian scouts and the Piarist fathers, after the fall of communism in Hungary he used his professional contacts to establish MBA and other scholarships, support scouting programs and other similar initiatives enabling young Hungarians to study in the U.S., or young Hungarian Americans to spend time in Hungary. He is still actively seeking ways to support young Hungarian intellectuals as the Honorary Consul of Western New York.

***

The story of your immigration in 1956 is somewhat unusual…

I was ten years old when the Hungarian Revolution broke out in 1956. At that time, from the age of 7–9 we were already socialized by our parents about what we should or shouldn’t say to others. If we were sitting at a table and there was someone there we were not supposed to speak in front of, my mother would give me a good thigh squeeze or kick my ankle to shut me up. At the Ferenc Rákóczi II School in Gyöngyös, Hungary we operated a small toy printing press to create a lot of flyers proclaiming: ‘Russians, go home!’ in Hungarian and in Russian, and threw them out of the school window. My benchmate, László Halmai, with whom we cooperated concerning these activities, was the best student in the class, but as a consequence was excluded from all opportunities for the rest of his life in Communist Hungary. Eventually, he became a Franciscan monk and an excellent math and physics teacher.

I was also an excellent student, but at the end of that November, sometime after the revolution was crushed, we wrote a math exam which I hadn’t studied for, and for the first time in my life I got a D… I went home very nervous, and seeing how upset my mother was, I kept thinking I was in big trouble… However, my mother sat me down and said, ‘My dear son, the revolution is lost, they are rounding up people and your father and I are thinking of leaving the country. But we know that you have your school and friends here, you don’t know any other languages, and we don’t even know where we are going or what we are going to do there. Would you take the risk of fleeing with us?’ It was very nice of them to ask me, and it was a lifeline for me, so I immediately said yes and hid the gradebook in my underwear…

How did you manage to flee?

My parents were divorced by then, and my father worked as a physician in Budapest. He arranged for us to take the train to Sopron on 1 December, 1956. My mother fabricated a fake official-looking document claiming she had some business with the Sopron-based wine company. This helped when the border guards boarded our train as it approached the Austrian border. Thanks to my father, we were able to stay in the hospital in Sopron for the night. The next day we searched for someone to take us to the border. Our guide took us to a small forest and let us out, advising us to cross the forest, and the other side would be Austria. However, it wasn’t that easy. Before reaching the Austrian border, we had to cross a country road running through the forest, and every 15–20 minutes the border guards would pass by. Suddenly we heard voices. My mother instinctively left us and went towards the voices to draw attention away from us. She came back 15 minutes later and told us that she had met two very nice Hungarian woodcutters, former border guards. They advised us to wait until dusk, and they would return to help us cross to the border. Just as we were crossing the road with them, a border patrol vehicle with searchlights suddenly appeared around a bend in the road. I was sure that it was the end of my life… We dropped flat on the ground and the lights passed over us. We proceeded for another 150–200 meters, when the men told us: we should kiss the ground, because we would probably never see our homeland again. They pointed out the Austrian Border Guardhouse and left. As we approached the house, the door suddenly opened and two border guards with machine guns stood in front of us. For the second time within an hour I thought I was going to die…

But they didn’t shoot at you, right? What happened to you in Austria?

No, they started to speak to us in German, gave me an apple, and took us to the nearest village, where a very nice Austrian peasant family took us in for the night. They even gave us dinner. They had a 15-year-old son who turned out to be a football fan, just like me. At the time, Vasas Budapest won the Central European Cup, beating Rapid Wien. After the trauma of fleeing, it was a source of pride for me and I couldn’t resist telling him: ‘We beat you 8–2 last month and won the Cup.’ For my ten-year-old self, that was the most important thing… and my gradebook hidden in my underwear. Next day they took us to Eisenstadt and put us in a former Russian military barrack.

The Austrians offered for us to visit Italy for a week or two as part of a large Hungarian refugee group before emigrating to our final destination. Three days later, on Saint Nicholas Day, we were transported to Vienna by bus. There, a boy about my age with his father came up to me and gave me his presents from Saint Nicholas… I still get very emotional about it… We continued by train to Tarvisio, Italy, where I saw and ate mandarins and oranges for the first time in my life. When we arrived in Rome, we were taken to a very nice and cultured refugee camp for families with children at Monte Mario, outside of Rome. The food wasn’t good, so some Hungarian women took over cooking in the camp. Overall, we were treated very decently. My mother even got a job in a cosmetic salon, and we could visit Naples and Venice. Camp life became boring after a while, people began to get anxious. It was not until April 1957 when officials started to show up. First, the U.S. Army recruited young people, with the commitment that after five years of service they’d be granted U.S. citizenship. Next came the Australians. The Canadian delegation arrived a few days later, and we accepted their offer. The Americans showed up 10 days later, but there was no way for us to have known that…

Do you have other memories of the Italian refugee camp?

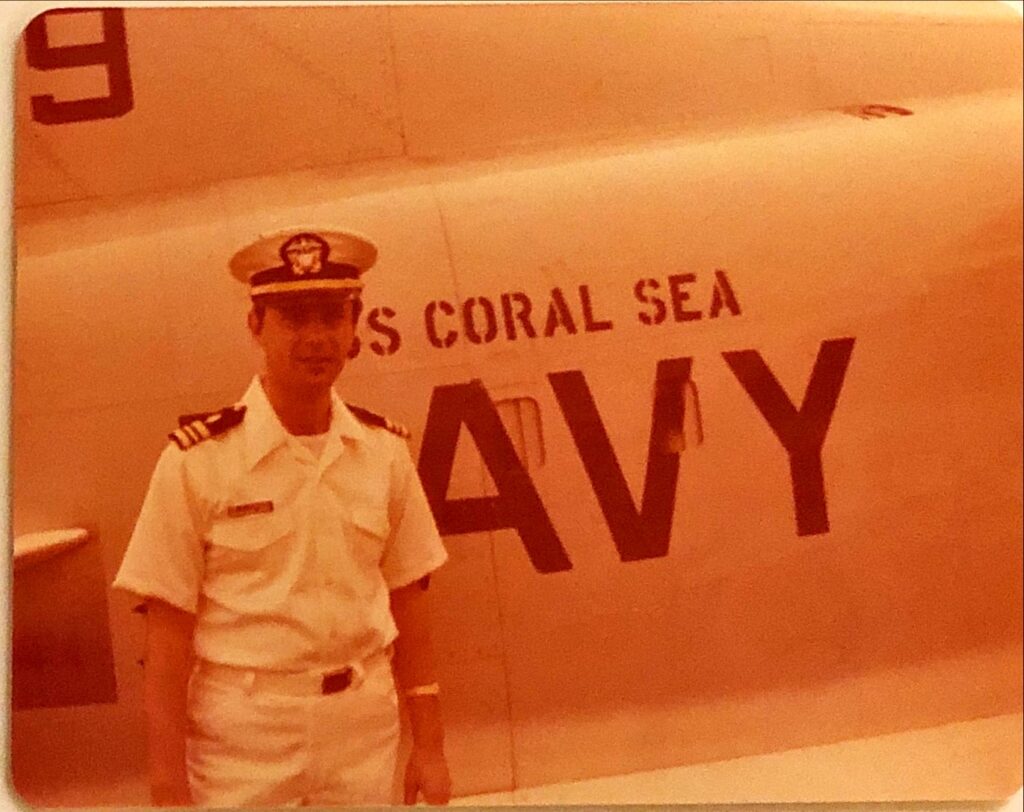

There was an American aircraft carrier, the USS Coral Sea, that docked in Naples, and the young people from the refugee camp were taken to visit. My guide on the ship was an 18-year-old American sailor, Dale Whigham, from Ohio. All I could say in English was, ‘My Name is Peter, I’m from Hungary.’ He was very patient showing me around, even though we couldn’t communicate with each other. It was the experience of a lifetime. I have a photo of us on board. Twenty years later, when I enlisted in the Navy, I was stationed in San Francisco, where coincidentally the USS Coral Sea was based… In 2018 I found and reunited with Dale.

I have another very memorable story. There was a soccer match between Budapest Honvéd and AS Roma in Rome, and Zoltán Czibor from the world-famous Hungarian Golden Team visited us the following day at the refugee camp, and played some soccer with us. I played on his team and he gave me a goal pass! I even have his autograph from that day. These are indelible memories for a refugee child… As for my math gradebook: I secretly tore it up and flushed it down the camp toilet in Italy. I finally got the courage to tell my mother about it only two years later. The thought never stops haunting me that the first time I almost failed in school ended up changing my whole life…

How were your first years in Canada?

I can’t say that they were the easiest years of my life… When I look back at old pictures and see how I looked in my European refugee clothes compared to how the Canadians looked, classmates with whom I couldn’t exchange a word because I didn’t speak English… My parents didn’t talk like or act like the other kids’ parents either; all at a time when I was entering the challenges of the teenage years. The lifeline for me, similar to other Hungarian refugee children, was the Hungarian church and Hungarian scouts. There were about 50 or 60 of us in the Árpád Boy Scout Troop No. 20 in Toronto, with whom we shared the same life circumstances. We had scout meetings on Thursdays, folk dance group on Saturdays, and attended Hungarian mass on Sundays, where we served as altar boys. During the summer we went to scout camps. These experiences gave us inner strength and a community in this new country.

When we left Hungary, I had just started fifth grade, and then missed nearly two years of schooling as a refugee. I was able to continue my education in seventh grade. My parents put a lot of emphasis on education, and sent me to an excellent private Catholic school, De La Salle in Toronto. Interestingly enough, I was learning the same math in seventh grade in Toronto that I had started in fifth grade in Hungary. When my mother remarried, her husband got a job in Fort Erie, a small town at the U.S. border, and we moved there. The quality of the local schools was terrible, and my mother panicked and proclaimed that she would rather return to Communist Hungary than let me attend the local school. But again, God threw me a lifeline: there was a very good private high school across the Niagara River in Buffalo, New York, founded and run by Hungarian Piarists. I enrolled there in 1959 and my parents followed me to Buffalo in 1961, when my mother got a job at Roswell Park Cancer Institute. My brother was born in Toronto in 1958, my sister in Buffalo in 1962.

You said you were heavily influenced by the Piarists. Why and how?

The Piarists fled Hungary and came to the U.S. after World War II and set up a boarding home for Hungarian immigrant children in Derby, New York. Subsequently, Father Gerencsér established the Calasanctius Preparatory School for Gifted Children, which was a selective educational institution. Perhaps they even went into excess in this regard: at the age of 13 we had to study from university textbooks. One could choose from 8 to 10 languages, including Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, and of course major Western languages, plus biology and chemistry at a college level. It was very demanding, but at the same time I was instilled with a life philosophy that became a guiding principle throughout my life. Their teaching method was to introduce us to the most virulent anti-Christian critique and allow the students to create a defense for their Christian beliefs. To this day, I read philosophy and theology extensively.

At 15, it occurred to me: I have a great life, with all kinds of opportunities. The only limit to my success depends on my motivation. This was made possible because so many young people have died or their lives were ruined in Communist Hungary… When I heard the saying, ‘Survivors carry the credentials of the forever silenced’, it really touched me. Due to the values instilled in me by the Hungarian scouts and the Piarists, as well as the American attitude of giving back, it slowly emerged as a conviction that I had a responsibility to help others who were less fortunate.

Before we continue with that, tell us about finding your profession.

My father was a physician, so I suppose there was a subconscious pressure on me to choose that career path. My mother would have been very happy if I’d become a research doctor, but this was not my calling. I spent two summers working in a research institute, but decided that I’d rather operate on people than experiment on monkeys and rats. I did my undergraduate education for three years at Notre Dame, then was accepted to medical school in Georgia, where my father lived at that time. After I got my medical degree, I did an internship at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, followed by residency training in Ophthalmology at the University of Buffalo. Subsequently I had a fellowship training in Retina and Vitreous surgery at Baylor University in Houston.

In 1978 I started my two years of military service. I chose the Navy, and was stationed at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in the San Francisco Bay Area. We treated active duty personnel and veterans, as well as their dependents. The San Francisco area was a choice spot to be stationed, and normally only more senior officers would get this assignment; however, as there were very few retina surgeons at the time, I was stationed there with the rank of Lieutenant Commander and assigned to establish a retinal surgery practice department. I enjoyed my job, so I asked for an extension for an additional year. I also met my future wife, who I ultimately ‘kidnapped’ from her parents and her dreams…

Tell us some more details about meeting her.

Kati’s father is Japanese, her mother is of German and Great British descent, while she was born in Texas. She was studying biology at U.C. Berkeley and was accepted to veterinary school. Her father was an Air Force retiree, and when Kati had an accident playing tennis, she came to our hospital where I treated her. She came for a check-up every month or two, and we had a good chat each time. When she heard me speaking Hungarian, she became very interested, and enrolled in a Hungarian language class at Berkeley. When I returned from my first trip back to Hungary since emigrating, I invited her to dinner and showed her my photos. Eventually we were engaged, and she had to make the difficult choice of giving up her ambition to be a veterinarian versus marrying and moving to Buffalo, where I planned to set up my own retina practice. Kati is a very smart woman; she knew right away how to help me establish my practice, which was very successful from the start. I’m more of a visionary, she is operational, implementing my ideas with practicality.

How well did she learn Hungarian? How did you talk to your children?

After our son Nándor was born, Aunt Irénke from Transylvania took care of him during the day. Kati soon realized that if she wanted to know what happened to her child during the day, she had to not only understand Hungarian, but speak it as well, as Irénke didn’t understand English at all. She became an assistant for my mother as a registrar for Hungarian scout camps. As her Hungarian improved, she joined the Hungarian scouts, completed the leadership training camps in Hungarian, and is now one of the leaders of the assistant troop leader camp. Four years later, Anna was born, followed by our twins Rózsi and Réka. They were all members of the Hungarian scouts. My parents and I spoke to them in Hungarian all the time. Kati and I spoke Hungarian to each other, but she spoke English to the children. These language house rules were always respected, the children never mixed the languages. When Nándi was three, we were visiting Italy at the time when Libya was bombarded by the Americans. I asked Kati to speak only Hungarian, but Nándi shouted at her, ‘Mommy, you have to speak English to me!’ and our alibi was blown. Our children’s spouses are not Hungarians, so they speak in multiple languages with their own children, too. For example, Anna lives in Hungary, but her husband came to Hungary from Denmark. He speaks Danish, while she speaks English to the children, and the kindergarten and school that they attend are Hungarian. It’s not easy but can be done, it just takes awareness and lots of self-discipline.

You’ve told us about the roots and finance of your philanthropic activities, but what exactly led you to start the first scholarship program?

Hungarian scouting has always instilled in us a healthy patriotism, but if I have to pinpoint a specific event, it was the 1989 scout leadership camp, where nine young scout leaders from Hungary took part in the Troop leadership training. One of these was András Edöcsény, who approached me a few years later in his capacity as the director of studies at St. Ignatius Jesuit College in Budapest, asking for my help to organize a fundraising in Buffalo for the college. My thought was if I organized a dinner at the Hungarian Social Club, I could raise a couple of thousand dollars. Instead, I offered my connections to the local universities to ask for scholarships for talented young Hungarians. I took András to the Jesuits’ Canisius University and to the Vincentians’ Niagara University.

Prior to that, I contacted these universities and informed them about the political changes in Central and Eastern Europe, including Hungary. I believe a good democracy requires experts in business, media and political science. I asked for scholarships for two year MBA studies. My view was that this is long enough to understand what America is all about, and it is impressive to return to Hungary with an American diploma. We ended up getting András four full scholarships at the two universities. In today’s terms, this was worth $70,000–$80,000 a year per student—I certainly couldn’t have raised that much money with fundraising dinners. Soon three or four other universities approached me as the initial scholarships were very successful. There were years when 15 or 16 excellent students were studying here simultaneously.

Was this program focusing only on business?

No, there was another program focused on pastoral care. Once I saw a nun comforting a patient after an operation. She explained that she was a pastoral caregiver. I told her this was an area of need in Hungary, and asked her to help with students from Hungary. This developed into a program for two–three pastoral care students per year. András Edöcsény also brought up the idea of medical students coming to the U.S. as well for training. I approached the director of the hospital where I was doing surgery with the idea of having senior medical students come here for two–three months of training in various departments. He said yes, and the program took off. Later, I was contacted by the Hungarian Medical Association of America to continue that program under their umbrella. I accepted the offer and ran it for four years. We’ve had Hungarian medical students coming to Buffalo ever since. In total, 250 students participated in the MBA and Pastoral Care programs over the years.

How did you manage all of this on your own?

After running this program on my own for three or four years, I sat down with the alumni and told them: I’d love to continue, but I can’t do it alone any longer; so I asked them to help out. They were very receptive and set up a board of trustees to select the students. They did an excellent job; there was never a problem with any of the students. They also organized several Hungarian exhibitions at the Niagara University. Three years ago we inaugurated a statue of Lajos Kossuth at Niagara University as well.

Later I told them about another project worth thinking about: a youth entrepreneurship program. When I was in the Navy in San Francisco, we did research at Stanford University. Visiting Silicon Valley once a week, I loved the enthusiasm and ’can do’ attitude of the young people working there. Based on that experience I suggested establishing a program for 15–17-year-old high school students in Hungary in entrepreneurship. It’s a one-week course for a group of 20–25 students, who are given the basics of how to start a business and then have to present a virtual company. We started more than 20 years ago, and it’s been working ever since.

You also supported the Hungarian scouts directly for years, right?

One of the programs I supported was a three-week trip to Hungary for 15–20 young teenage scout leaders. They bicycled 300 kilometers for a week, kayaked on the Danube for another week, and then spent the third week in Budapest. For the first 10 years, Kati organized and ran the trip, then others took over. When the Hungarian government established the well-organized Rákóczi camps, and the scouts of the various Hungarian scouting associations started rafting trips in Hungary, we stopped. While our tours were great, what we have now is much better. You always have to know when to stop and look for other unfilled needs.

What other projects have you looked for?

Firstly, we organize a ten-day study trip for American MBA students to Hungary, for which they get credits from their home universities. Secondly, we are developing a program to prepare highly motivated and talented Hungarian high school students to apply to top American and European universities. Thirdly, we organized gap year programs for high school graduates before starting university. This one-year program allows them to travel and work around the world, to help decide on their course of studies for the future. The fourth project is to bring 2–3 students and young teachers from Hungary and Transcarpathia to the Hungarian Summer School Camp in Fillmore, New York.

Read more Diaspora interviews: