This is the English version of the interview originally published on Magyar Nemzet.

The Hungarian folk dance movement started in North America in the 1970s. Kálmán Magyar Jr, a successful lawyer in Canada and America, still considers the folk music education his parents provided, as well as performing and entertaining Hungarians living abroad, extremely important.

***

You work as a lawyer but have never stopped making music. Where does this vocation come from?

My parents weren’t musicians, but my sister and I were sent to violin lessons with Erika Boyd, who learned the observation, listening, and imitation teaching methodology from Japanese master Suzuki. This is excellent for future folk musicians. Later, at the Manhattan School of Music, we engaged in more complex studies: classical violin and viola, music theory, ear training, composition, choir, jazz, and chamber music, and even played in a symphony orchestra. We studied with the school’s director, Stanley Bednar, who cared little for repertoire and worked more on tone, posture, the use of the bow, and musicality. He asked me to stop playing the Transylvanian contrapuntal accompaniment (balanced accompaniment emphasizing the rhythm, mainly played on the bass violin with a deeper tone) because it made my left wrist very tight. If I played it one night, he immediately noticed it the next morning. Nevertheless, I continued to play folk music, especially in the summer, when I could learn from people like famous Hungarian folk musician Béla Halmos in the camps in Jászberény and elsewhere.

Your parents led the Hungária folk dance group. Later you also joined it and even formed the band Életfa (Life Tree) with your sister. Why was it important for you to practice folk music in so many ways?

My parents formed the Hungária children’s group when we were also children, in which we performed several times. Like many other first-generation immigrant children, I spent my weekends cherishing my Hungarian heritage. I went to folk dancing every Friday night, Hungarian school on Saturday mornings, scouting in the afternoons, and then altar services, community lunches, and cultural commemorations on Sundays. I didn’t have much of a social life in secondary school, I didn’t play sports, so I missed out on many of the things that are part of life for young people in America.

I felt comfortable in the Hungarian community, although I was a bit of a black sheep: the aforementioned activities were only secondary to my music studies.

The latter was the foundation of all the good things in my life: my university studies, my marriage, and my vocation. In 1987, we founded the band Életfa, at which time we no longer danced at the Hungária, but my sister and I often played music together and we also found a double bass player. Attila Papp was a member of Hungária, so we started as a house band, but soon we also started to be invited to perform in Toronto and Montreal, and we regularly played in New York at the dance halls of the Hungarian House, too.

Then, during my university years, new members joined Életfa again. My sister graduated from medical school in Hungary, after which her husband joined us for contrapuntal accompaniment and my wife for singing and dancing, so we already had an extended Életfa family. Since then, it has grown into an open band of family and friends, even a movement.

You mentioned that your life had been different from that of your contemporaries. How difficult was it? How did it feel when your parents said no to your quitting music?

We have gone through this dilemma with my family, too. When quitting music, my daughter and I agreed that she had to take up tap dancing instead, which she has been doing ever since, after school, 25 hours a week. My son also had to stop playing music when he started playing professional football. But last year he studied in Hungary for a year, where he began to play the violin again. Thanks to the Óbuda School of Music, his musical knowledge is now much more developed, and he has a different approach to folk music. Sometimes he tells me off when I don’t play authentically, saying ‘I’m faking it’. And he is right. When I was a teenager, I didn’t have access to the original musical materials. My parents could have been more lenient too, but with them, music was the only thing on the table. It is still very difficult to say no to Kálmán Magyar Sr today. He believes that you can’t stop doing things, but you have to stand behind them even harder. That is why he was able to achieve so much in the field of folklore.

Today you play in Canada with the band Gyanta (Resin). Have you ever been in danger of burnout?

The band Gyanta was formed by musicians from Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa, and now I’m the one leading it. We play mainly at dance events, sometimes festivals and balls, with the addition of stage performances. I’ll be 50 in November, and I really feel now that making music, with all the travelling and little sleep, is more for the young. This year I’m taking my son to see Gyanta perform, so he can witness what we do. And I would like to take on less and less, especially since we are moving to Florida in a few years. I’ll come back for a gig or two from there as well, but I will not be able to take all the East Coast travel anymore.

I see the future in young folk musicians, and I like to inspire others, but it’s something that is hard to pass on.

A wise dancer, Norbert Kovács, said to me a few weeks ago that people in Hungary should learn from those in the diaspora to cultivate their culture with a pure heart and love. What is needed is not a competitive, one-upmanship, critical attitude, which is unfortunately the case within the movement, especially in Hungary. My son is right when he tells me that I don’t play accurately, but what is most important to me is that everyone has fun. This is the attitude that should be taught.

How ‘Hungarian’ is the youth community in America today? How much do they go back to Hungary?

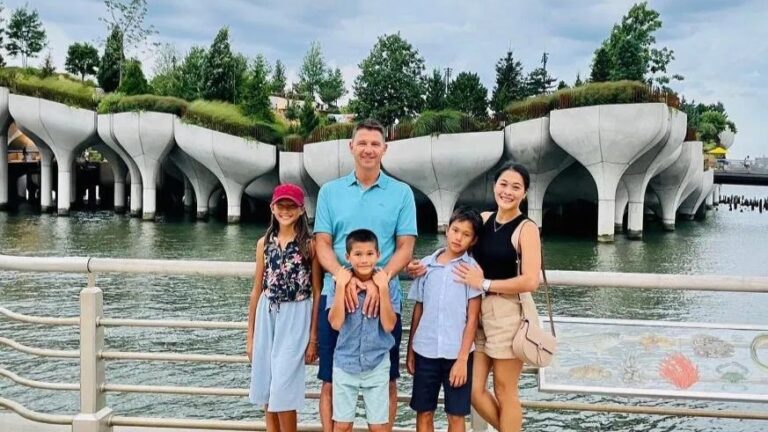

When I was born, my parents had only lived in America for ten years. Naturally, their circle of friends was all Hungarian, with only a few American colleagues or neighbours. Those born here, on the other hand, have a more mixed circle of friends, and our children have an even more mixed circle. One could criticize my children, for example, for not going to Hungarian school, scouting, or church. However, our American and Canadian friends might say as well that they are not American or Canadian enough. My daughter Csenge studied at the Bartók Conservatory in Budapest in ninth grade and wants to go back. She is now studying psychology and economics, will finish university next year, and then wants to get a master’s degree in Hungary and continue her folk music studies there. My son Soma was in eleventh grade also in Hungary last year and is now finishing secondary school here. He has not stopped playing folk music and has found his place in Gyanta, too. My younger daughter Bíbor is only in tenth grade, but she will probably not study in Hungary, as she cannot leave the dance studio for a long time.

How do you build the folk dance movement today?

No longer by performing at events, but with special projects. As a first step,

during the pandemic, I launched a podcast titled Táncház Talk in English.

On Facebook, I saw a Serbian guy from Chicago playing music and talking about events from the eighties. I found it so funny that I started something similar, which later evolved into an interview show. More than fifty broadcasts of Táncház Talk teach about Hungarian folk music and the Hungarian dance house movement in America. My children speak Hungarian, and my grandchildren might, but my great-grandchildren probably won’t, so I want them, too, to be able to use what I’ve collected.

Another initiative I’m working on is an awareness-raising organization promoting tours, camps, and festivals. My parents founded a similar thing in the seventies, but it has died since they moved back. Now we are starting a new organization called the Hungarian Folklife Association, where everything related to Hungarian folk culture in America will be available. There will be a common calendar, for example, to avoid clashes, or a historical catalogue describing the entire Hungarian folk dance movement in the US to date. In America, not only Hungarian dance companies have been created, but also an international dance movement, which is very special and unique. With my legal and musical skills, I hope to pass on the knowledge to future generations as well. However, I have to do it completely differently from my parents, as young people can only be reached through apps now. I want to create something like the Hungarian Heritage House. Part of the project is also the University of Chicago, a hands-on skills meeting place for folk dancers and folk musicians. There will be a course for dance teachers on how to teach the Mezőség turns or for musicians on how to run a dance house.

Tanchaz Talk INTERVIEWS – On the Road with Gabor Dobi and Attila Krasznai – November 22, 2022

Recorded in a Subaru during a wintery drive on Ontario’s highways, Gabor and Attila join Kalman on the road to discuss a wide array of topics. Gabor is one of the main figures in Canada’s Hungarian folk dance scene, and Attila is one of North America’s top Hungarian folk musicians.

Is the Hungarian Heritage House also aware of the initiative?

Of course. According to Director General Miklós Both, they cannot help with the creation, but they can cooperate with the finished project. I would like to finish this off if only because when I was wandering around the Budapest building last year, I happened to come across a cassette in the database that said ‘Béla Halmos’ conversation with Kálmán Magyar’ on the back. Incredibly, out of hundreds of thousands of cassettes and tapes, I touched just that one. That is what I call a real confirmation.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.