Click here to read the original article.

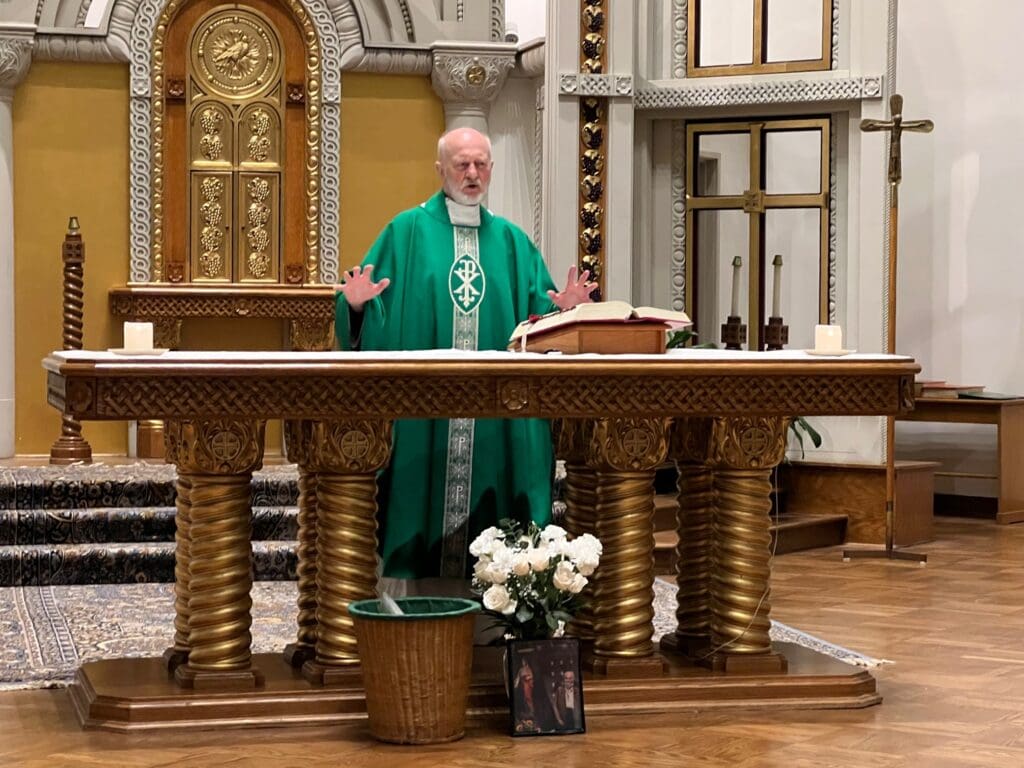

As the only Hungarian priest in New York State, Father Iván Csete travels 160 kilometres by train every two weeks to New York City to offer mass to the dwindling Hungarian community living there. He renders this service alternately each week with the Hungarian parish priest of Passaic, Father László Balogh. After a Hungarian mass in New York in September, I spoke to Father Iván about his adventurous life, during which he revealed that at 86, he still has plans for 14 more years.

***

At the mass, you mentioned that you had been retaliated against for the cross you wore already when you were in secondary school.

When I applied for secondary school in 1950, at the age of 14, I was an excellent student, so there was no reason not to be accepted based on my study results. But because of my family background, I was class-alien, so in the admissions office, Headmaster Csernai pointed to the cross around my neck and said: ‘Son, until you remove that, you’re not coming here’. Therefore, I couldn’t get into secondary school, which hampered my preparation because I wanted to be a doctor. I ended up in a commercial vocational school; I hated accounting…After graduation, I was ‘naturally’ not accepted to university either, so I worked at the hospital in Zirc for a year, while I was preparing for university admissions. My father had medical contacts, such as Imre Láng, a distinguished brain surgeon who had been on an American fellowship, at the University of Szeged, and he helped me get in after I had taken the entrance exam.

So, in 1956, you were a twenty-year-old medical student in Szeged and an active participant in the revolutionary events…

Yes, we were the ones who started the university movement: we tried to change the system through the Association of University and College Students (AHUCS). Initially, only within the medical school, in a clever way, demanding educational reforms, such as abolishing Russian, as German, French, and English were more useful for doctors, and then in other ways as well, for example, by initiating the abolition of compulsory military service. However, in no time at all, all that became politics. You know, the reburial of [Communist politician] László Rajk was on 6 October, and the rehabilitation of the executed comrades was a huge event at the time. We wanted free elections and an end to compulsory collective farming so that private estates could be preserved.

We also realized that as long as Soviet troops occupied the country, we would not succeed.

Thus, we came up with a list of sixteen points [containing key national policy demands], the essence of which was to withdraw Soviet troops from the country.

At my initiative, we included the restoration of the old Hungarian coat of arms among the points; that is, at first only the Kossuth coat of arms, because the Holy Crown would have been too much to bear at once for the Soviets. The secret police were alerted, but they did not want to strike straight away, because the ideology of the time was that Stalin was the main culprit, and the others were all ‘good guys’. Therefore, they tried to handle the situation delicately; they didn’t want to respond immediately with terror but sent a State Protection Authority (Hungarian Államvédelmi Hatóság, ÁVH) team down to Szeged to watch us and decide whether to strike or not. We took advantage of this by sending delegates to other universities, to Debrecen, Pécs, and Veszprém; I went to Miskolc with a friend, Karcsi Hámori, and the secret police had no knowledge of that. I went to the university assembly in Szeged on 21 October, talked to students, and then went up to Budapest, where the Revolution broke out [on 23 October]. We were really looking forward to the arrival of the Americans…When the cannons were fired at dawn on 4 November, I was delighted to see that they had finally arrived…However, when the Russians crushed the Revolution, the student organization of which I was a member told me not to be naïve and to run away, so I finally escaped with my brother and some friends to Austria.

Why did your brother emigrate?

He had no future under communism either, because jazz was considered reactionary capitalist music at the time, and was banned, but Jóska and his band still played King Cole, Big Band, Ella Fitzgerald, and Louis Armstrong in two permitted nightclubs, the Paradiso and the Pipacs…From Austria—where the refugees were nicely sorted out by the free countries—I wanted to go to Germany to join the West German armed forces because the communists were making such propaganda against the Germans that we thought they were ready to attack the Soviet Union together with the Americans…As we already know, that was not the case, and since my brother wanted to come to America for music and our friends for family reasons, I finally joined them.

What were your first years in America like?

A hundred Hungarian boys, including me, were taken to a college in Vermont, Saint Michael’s College, to study English. After three months we were sent to work—I became a waiter, then a carpenter’s assistant. Some of the Hungarian boys were placed in universities, because the major universities offered scholarships to Hungarians, for which even those who were not university students applied—no one could check their credentials at the time. I was accepted to two places: Dartmouth College—one of the best boys’ universities here, part of the so-called Ivy League and the Jesuit Fordham University. I chose the Catholic university, where I completed the so-called pre-medical training. Here, medical studies last a total of eight years: four years of pre-med and four years of ‘real’ medical training. In the meantime, I’ve had all sorts of jobs, such as dishwashing at the Empire State Building and cleaning in other places. Since I had no money, I decided to go to Europe to study because it was cheaper there. I knew a little German and French, so I thought about these two countries. In the meantime, I did not abandon Hungarian political activism either—we made anti-communist speeches, took part in demonstrations in front of the Russian Embassy, etc. At that time, Charles de Gaulle was the great French statesman who stated that ‘Europe stretches from the Atlantic to the Urals’—that’s our man, I thought, and thus I chose France. There, too, I first tried studying medicine but eventually gave it up…

Why did you do so if you had studied so much before?

I had no real ambition; I only chose it because of my father and grandfather, who were excellent doctors. In Paris, I was rather interested in history and political science, but I had to learn French first. I got a master’s degree from Middlebury College, one of the best language schools, and then enrolled at the Sorbonne, where I chose Kossuth’s Danube confederation as my subject, and in parallel attended Sciences Po as well [Paris Institute of Political Studies], a famously snobbish diplomatic school. Meanwhile, in the summers I worked here in America, sometimes in three jobs at once: some days I was an usher at the Metropolitan in the evening, a cleaner in a school at night, and a typist during the day; I had learned to type back in the commercial school. I barely slept, but in three months I had saved enough money to live for a year in Paris in a small attic without a toilet.

When and how did you become a priest?

Well, I met a very nice and religious French girl. Meanwhile, I had a great love affair here in America, but I knew it was time to get married because I was already around thirty. The French girl, Emmanuele Mallard invited me for coffee and then to a retreat. I liked her very much and I thought she must have plans for me, she must want to fix me, so I said, ‘why not?’. We were in a famous retreat house at the foot of the Alps, with about 200 other young people, and we were not allowed to speak a word for a week—it was very purifying. We could only talk to the priest and sing, but not to each other, only exceptionally, ‘in private’. So, one day I invited Emmanuele to my room and asked her if we would get married. It wasn’t very romantic, I admit—she looked at me strangely, smiled, and said ‘no’ and that we didn’t even really know each other, that wasn’t what she had in mind, and that wasn’t why she had asked me there. It was a big slap in the face, but from then on, my attention was no longer on the girl, but on the priest. I thought there was communism at home, half of the world was godless, didn’t know God or didn’t consider Him important, and nobody wanted to be a priest anymore…

Thus, out of some kind of Hungarian defiance, I decided that I would become a priest.

Of course, there were other reasons for this decision as well. One was that I was a very ambitious young man, I had many degrees, and I was just about to finish my doctorate at the Sorbonne when I was confronted with this sentence from the Bible:

‘What good will it be for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?’ (Mt 16:26)

My other defining experience was the eucharistic adoration in the Sacré Cœur Basilica in Paris. This church was built to atone for the sins of the nation; above the mosaic over the choir, entitled The Triumph of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the following is inscribed: ‘To the Sacred Heart of Jesus, France fervent, penitent and grateful’. There is continuous eucharistic adoration in the Basilica, women by day, men by night. I went to Sunday evening masses as a student and once a priest asked for a volunteer from the pulpit for that night’s adoration because someone hadn’t come, and I raised my hand. I kept vigil until 4 in the morning. From then on, I was invited to be a regular participant in the adorations. It was around that time that Emmanuele ‘came into my life’, who later, by the way, became a nun.

Why did you come back to America?

My brother got married and had two sons, but as great a jazz pianist as he was, as artists usually are, he was a bit unstable as well. Unable to make a living from art, he worked all kinds of jobs. Eventually, he and his wife divorced, and he needed my support. My brother was a big anti-communist, so much so that he once refused to accept a tip from a rich Chinese man and therefore was fired from his job. So, I started looking around for places to study here, and I thought, I’ve studied so much already, they must recognize some of it somewhere. But it was not the case—I had to study for four years at St Joseph’s Seminary & College in New York, where I was a so-called special student (Editor’s note: someone who does not attend classes to get a degree) for a year because I wanted to go to the Collegium Pazmanianum in Vienna to have a closer relationship with Hungarians.

When Cardinal Mindszenty was here, we met. I introduced my 12-year-old nephew to him, and his first question to him was: ‘Does your father speak Hungarian to you?’. He was very happy that I wanted to be a priest. However, my plan fell through; Mindszenty died, and [Rector of the Pazmanianum from 1971 to 1987] Reverend Egon Gianone told me that I should stay in America because I could serve the Hungarian community here as well.

I was finally consecrated as a priest in 1981, at St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York.

At that time, the only Hungarian church in New York was the St Stephen of Hungary Church, but it belonged to the Franciscan order, and I was not a Franciscan, so I could not go there. I was appointed to a nice American parish in upstate New York where there were some Hungarians; I was there for four years.

How did you end up in New York after all?

Eventually, I joined the Franciscans to serve the Hungarians even better. But even then, the path was not smooth. Fr Domonkos Csorba, OFM, Custos of the Holy Land, immediately put me in the very strong Hungarian parish of New Brunswick, where I was a Franciscan candidate for the priesthood for two years, and then he sent me to Boston to the novitiate. I was a novitiate there with two Hungarian Franciscans, one of whom was György Barnabás Kiss, who is now the ‘boss’ of the Hungarian priests in North America under Bishop Ferenc Cserháti. We were assigned to an Italian parish, where the Italians loved us very much, but the Novice-Master did not, so he had issues with whatever I did. For example, he didn’t like the way I sang the Gregorian chant, my suggestion to increase the confession time, or the fact that I wanted to watch the televised broadcast of the Pope’s visit rather than what he wanted to watch… Thus, I was finally sent to Burton, Michigan, which Father Csorba described as ‘the end of the world plus two miles’. There were a lot of Hungarians living there, too, and there was also a beautiful church, only the town was completely ruined. Later Father Csorba decided that the Burton estate needed to be sold. He bought a small house on 83rd Street in New York and set up a Hungarian centre there to strengthen the local Hungarian community. I had a nice little parish, the Church of Saint Thomas Aquinas in Forestburgh, New York State, which I ran for 17 years. There I introduced the Hungarian mass, which was attended by Hungarians sometimes from as far as 100 miles away. Unfortunately, that too was later closed.

What happened in New York during that time?

There was no Hungarian parish priest in the St Stephen of Hungary Church at the time. During the Great Depression of 1929, the beautiful church, which was built with money from Hungarian immigrants and had been consecrated the previous year, also went under during the crisis, so its management was handed over to the American province, which paid off its debt. There were many Hungarians living in New York at the time, as there are still, there were Hungarian Catholic, Calvinist, and Baptist churches. There was also a promise that there would always be two Hungarian priests in the St Stephen of Hungary Church, but neither of them could be a parish priest, which always caused tensions because the Hungarian priests were second in command in their own church. Then came the Hungarian regime change, and since the number of Hungarian Franciscans here had dwindled, a Vatican commissioner of Hungarian origin was sent here to assess the situation, and he concluded that the Hungarian Franciscans should either merge into the American Franciscan provinces or go home, since there are hardly any Hungarians left here, therefore, there was no reason to ‘push’ this Hungarian parish issue anymore.

So, the US archdiocese embarked on a major restructuring, closing sixty parishes in just two rounds, including the one in New York on 2 November 2015. They said they would merge it with the neighbouring Church of St Monica and allowed us to say Hungarian mass twice a year: on St Stephen’s Day and on the anniversary of the founding. I lobbied a lot against this decision, but I failed to prevent it. Father Csorba was allowed to stay for five more years, then he went home, and he still lives in Hungary, in the retirement home of the Esztergom monastery. After that, József Kormon was sent here, then two young Franciscans, but they didn’t stay long either;

in the end, there were no Hungarian priests left. Today, there are only ‘helicopter priests’ coming here,

like Fr Laci Balogh and myself.

And yet, we are not in the Church of St Monica now—what else happened?

It was a very chaotic transition. The last American parish priest here dismantled the great Hungarian youth group, causing serious financial problems, while a lot of important documents were lost with the relocation, the all-knowing secretary died, and the building has since become a school… The new parish priest of the Church of St Monica was very hostile to the Hungarians, he refused to cooperate with us, and in the end, we were not even allowed to play the organ. Therefore, in 2016, we took up Márta Keleti’s suggestion to move to the nearby German-founded Church of St Joseph, that is, here. Earlier, this used to be an all-German neighbourhood, but of the many German restaurants, only one, Heidelberg, remained, as well as one of the Hungarian restaurants, Budapest. Besides, Father Bonifác is very friendly—he allows us to hold one Hungarian mass a week.

And what about the present? How many people attend mass here and of what age group? They say it is only the elderly that go, but at today’s mass I saw several families with small children, and also, there was a Bible class before the mass, with people having a coffee together afterwards.

New York has always been a place of transit, because whoever can, sooner or later moves to a better place. The Hungarian House still exists, with a Hungarian school within it, but religion is no longer a priority. In the past, these were the last bastions of Hungarian Christianity: Hungarian school on Saturdays, and Hungarian mass on Sundays; these two were next to each other, and most people went to both places. However, today, believers have aged out, and for the younger ones, it is too much of a burden. Nowadays, there are 20–30 people who go to Hungarian masses, but today, for example, there were 45, mostly because of the Bible class before it, which we started this autumn.

Recently, the Hungarian community has started to grow a little, with a few young couples—mostly from Transylvania—coming here with their small children; a few years ago, it was really only the older people who came. Róbert Winer, a secular committee chairman from Nagyvárad (Oradea, Romania) has been promoting the Hungarian cause with all his heart and soul, producing the most beautiful Hungarian bulletin himself, and his grandchildren attending Bible classes here; and recently an agile lady, Ágnes Perényi, a paediatrician, has also appeared and is working with him to revitalize the local Hungarian Catholic community.

And my plan is not only to commute here but to be here most of the week. The parish does have a guest house, but I live elsewhere, and it doesn’t have an office, but I would still like to be more present: visiting the sick, taking care of the schoolchildren, and so on—as if they had a permanent priest. I live far away now, in Port Jervis, where I also have some work to do, which I took on of my own free will. Besides, I am retired, a free man, but I still help there, because I live there and I have my Hungarians from Upper Hungary there, whom I would never abandon.

Anyway, I still have 14 years left to live—I would like to use them all, although I know that Divine Providence should not be set a deadline…

All the photos in this article are courtesy of Ildikó Antal-Ferencz.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.