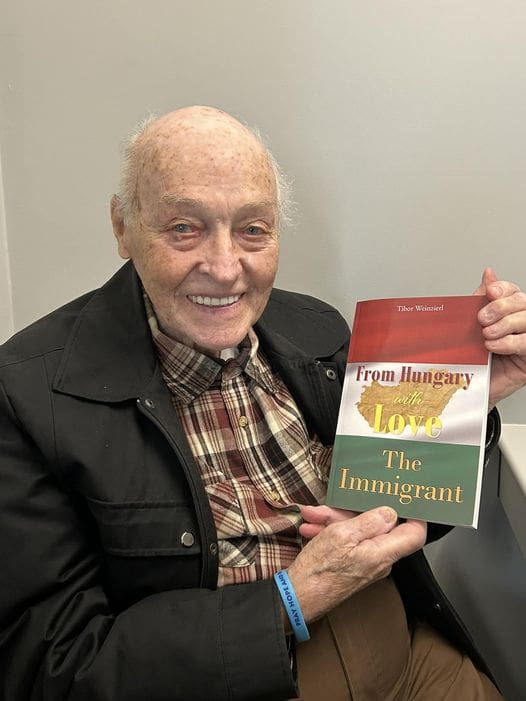

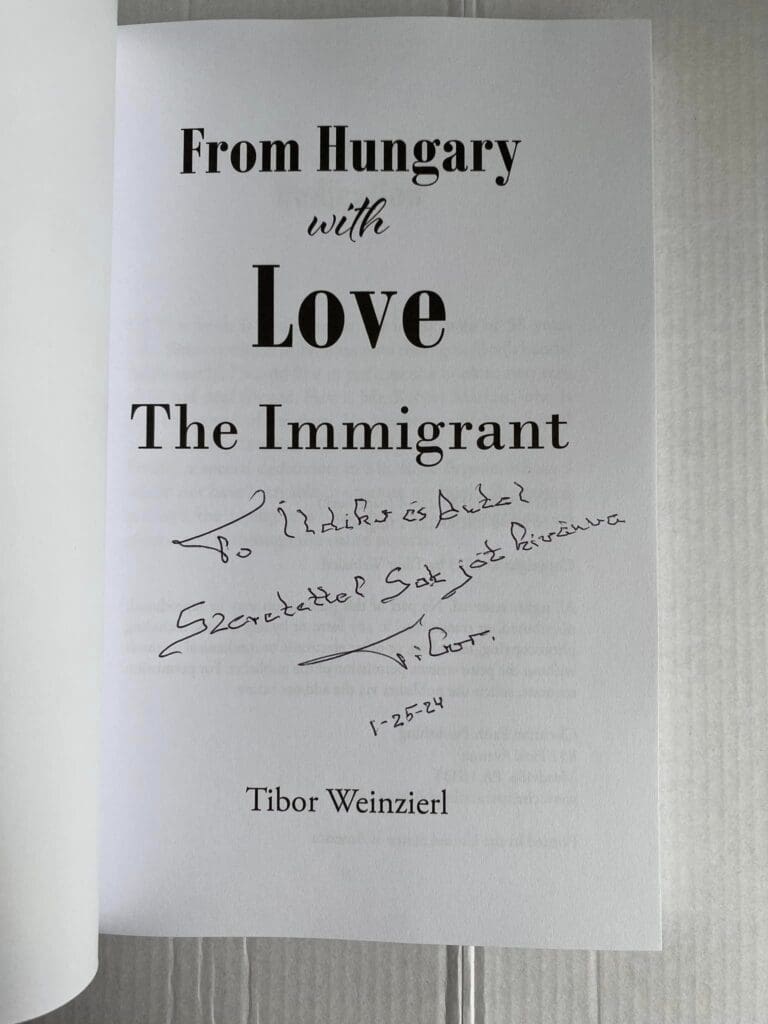

When the news of the release of this autobiography was posted in a social media group of Hungarians in Boston a few weeks ago, I was specifically made aware of the author as a potential interviewee. At that point I knew nothing about the 95-year-old Hungarian singer and violinist, who was well-known in Hungary, then Canada and later in Massachusetts. Since then, we have spoken several times and although we have never met in person, upon reading his book, I feel he has become a dear friend.

Written in plain (by far not literary) English and with unfortunate typos of Hungarian names, but filled with a lot of faith and love, this biography is not only a written record of a tumultuous life journey in an extremely readable form, but also a historical documentary.

Tibor Weinzierl was born on 2 February 1929 in Budapest; at the age of two and a half he met Baden Powell (‘BP’), the British founder of the scout movement in Gödöllő; at the age of five he started playing the violin, and then successfully pursued a variety of sports during his childhood. During World War II he attended a Jesuit school, which he eventually changed at the request of his military officer father to the military high school in Pécs (south of Hungary), where, at the age of fifteen, far from his family and friends, he had to say goodbye to his former sporting life and trophies, as well as to his beloved violin and promising musical career.

Military school started in September 1944 but was soon interrupted by the arrival of the Soviet forces. In December of the same year, following central military orders, they fled, first to Austria and then to the Sudetenland, further away from the frontlines. Their train to Erfurt was repeatedly attacked by the British air force, and then in the city they survived a 25-minute bombardment by the Americans. This was the first time Tibor saw a dead man still running for seconds without his head in place (a sight that still haunts him), and it was the first time he felt the fear of death and a strong homesickness. On 8 May 1945, in Orlick, a small town of Czechoslovakia, they received the news of the end of the war and the next day became American prisoners of war. They were treated well for two months by the US Army, but then had to be handed over to the Russians, who not only did not handle the young cadets with kid gloves, but offered the same and demanded the same as from the other about 150 Hungarian, Polish and German adult hostages: a long forced march to Strakonice, one meal a day, sleeping on concrete floors with bugs, humiliation, disease, lice, hard labor in breweries and cleaning the ruins of war along the roads.

They waited nearly two years for the Red Cross to intervene on their behalf as they were all well under 18; but that did not happen until the spring of 1947. They were released in September of the same year. After being away for two and a half years, Tibor literally fell into the arms of his mother, who was walking on the main street next to the train when he jumped off, thus avoiding the Hungarian military checkpoint. He re-enrolled in high school again and diligently tried to make up for the three years he had missed. When he fell in love with a girl named Klári, he tried to win her heart with a daring act: he crossed the sealed Austrian border back and forth to find her brother, a Hungarian Air Force private who had been in hiding in Austria for three years, to bring news of him to his family.

While Klári was a ballerina at the Hungarian Opera House, Tibor became a student at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music (Conservatory)

and had Zoltán Kodály, the famous Hungarian composer among his tutors.

He was also preparing for the Hungarian Idol competition that was launched by the State Radio at the time. He ended up being one of the four finalists out of 405 competitors (together with Márta Záray and Ákos Szente), thus launching his career in the music industry, and getting the artistic name Weinzierl at the ‘suggestion’ of the Communist management of the State Radio.

After his first live radio show aired on 28 July 1950, he was drafted for two years of regular military service to Nagykanizsa, a border town in southwest Hungary, 250 km from his home and from Klári, where they were trained for a potential armed conflict with Tito’s army. For Tibor, the only silver lining of this period was his meeting with his roommate, the talented pianist Miklós Kovács, who later became his sidekick on stage and a girl named Gitta, who he fell in love with. After joining the army’s official chorus, however, he was transferred to the Budapest unit and toured the country. By the time he finished his military service in 1952, he had lost both of his girlfriends, but landed several prestigious offers in a solo singer capacity from high-profile ensembles of that era, like the Péter Hajdú Quintet, the Czechoslovak State Radio Orchestra and Aladár Cirok’s Budapest jazz orchestra.

It was during this time that he met another lady named Gyöngyi, who confessed to him that she was married and was the mother of a three-year-old boy, but her husband was beating her and cheating on her, so she wanted to run away from him, but she did not have the courage to do so, because her husband was a member of the Communist Party. When the revolution broke out on 23 October 1956, with Tibor’s help, Gyöngyi fled with her son to Tibor’s family, about which his father was not happy, but his mother helped them to hide together. When the freedom fight was crushed on 4 November, Gyöngyi became very worried that her husband would track her whereabouts, so she filed for divorce remotely and quickly married Tibor, in the hope to apply for asylum in Austria as a married couple. The last time Tibor saw his father (who died in 1964) was when they soon fled for Austria. They managed to cross the border through cornfields in the roar of bullets, with Gyöngyi’s boy in Tiboe’s shrapnel-wounded arms. Since Péter Hajdú and his band also fled Hungary, they had a live show aired on 14 January 1957 on the Vienna radio station, offering hope to other Hungarian refugees.

They arrived in Montreal, Canada on 1 February along with several well-known Hungarian singers, such as Emília Rozsnyai and Ibolya Bán (singers of the Hungarian Opera House). In the Canadian refugee camp, Tibor met Steve Ness, a music industry insider, who offered them the basement of his house to stay there and helped them to find their ways in the local music industry later. While many were waiting in the refugee camps for a better life, Tibor took his fate in his own hands to support his family: he moved to the Ness’ house and took all kinds of jobs (he was a carpenter, a hotel helper, and a baker, and he was picking tobacco leaves on a plantation, too). At the bakery, he worked alongside a Hungarian doctor and a former military officer, which was not uncommon at that time. In the meantime, to establish his musical career, he learned French and English and practiced singing and playing the violin regularly. With his wife (her stage name was Pearl) they soon formed a successful duo, travelling all over the province of Quebec.

The happy immigrant life ended due to personal turmoil: the arrival of his wife’s family (first her parents, then her sister’s family) increased tensions between them, at the height of which Gyöngyi emptied their joint bank account and left with his son. It took Tibor a long time to recover from this disappointment since he basically left his family and country because of her, but after many tears and prayers, he slowly closed his past and focused on his future, one of the highlights of which was becoming a Canadian citizen in June 1962. Soon afterwards, he met Doreen, an English restaurant manager, who had divorced her alcoholic husband and arrived in Canada also in 1956. They soon married and she became his devoted wife and enthusiastic partner at work for the next 58 years.

The book tells the story of how they met and how they lived with an almost bewildering detail and honesty. They worked hard to build a decent life and successful career together. Their duo became so popular in the 1960s that Tibor was only able to fulfil an invitation in 1967 to Boston by the famous Cafe Budapest’s manager, Edit Bán, in the last days of 1969. The introduction led to signing a contract that eventually lasted for ten years. Their first performance was a huge success, with the local press welcoming them to the Boston artistic world. The secret of their success, according to Tibor, was that they played music that made the audience feel like they were in Europe, in Budapest or Vienna.

So they started to rebuild their lives in America, one of the highlights of which for Tibor was becoming a US citizen in October 1980. After 10 years, he left Cafe Budapest and worked in a number of restaurants, some American (e.g. Warner’s), some Hungarian (e.g. Csárdás, Duna). To supplement his livelihood, he learned to paint signs, which he did during daytime before his evening shows. The next chapter in his professional life was opening his own restaurant, Red Paprika, partnering with Steve Markus, the former chef at Cafe Budapest in Boston, and his friend, Joseph Vago, learning the ropes of restaurant management. After two years, he sold his share and worked as a manager, maître or sommelier at several locations. His longest job, lasting for 14 years, was in a brewery until its sale in 2006.

For a European, it is hard to imagine a 78-year-old unemployed man looking for work. Tibor even applied to McDonald’s and Burger King, where he was refused because of being overqualified, but was welcomed at Bertucci’s, an Italian restaurant, where he was employed from his 81st birthday as the oldest employee ever. He left this ‘dream job’ (which reminded him of his baker grandfather) six years later, at the age of 87. The final part of the biography details his daily caring for his wife. Doreen had initially battled breast cancer successfully, but she could not overcome the various complications and dementia. The lengthy description of the health complications and their daily lives all along (Tibor was also hospitalized with a stroke at a certain point) are interspersed with his childhood recollections and visits to Budapest with his wife and friends (first time in 1996). He regularly visited his wife during her last years in hospital, later burdened by the Covid pandemic, trying to instill a little home atmosphere and to spend family holidays with her and also to please her fellow sufferers with flowers and small gifts.

The life of Tibor Weinzierl (Várnay) is the

life of an extremely hard-working, persistent immigrant with a strong work ethic and a very deep faith,

someone who never hesitated to turn to God in all his moments of joys and sorrows, who was touchingly attached to his friends and employers, who were also a substitute for his distant family, and of course to his wife, whom he described several times as his sole partner since their parents were far away and they had no children. It is also very emotional to understand the love he expresses for Hungary as well as for Canada and the US. Finally, it is very touching how many times he cites his father’s words: ‘life is like a wheel that is constantly moving; after every low point comes a rise, and in the end all the good and bad experiences become just memories.’