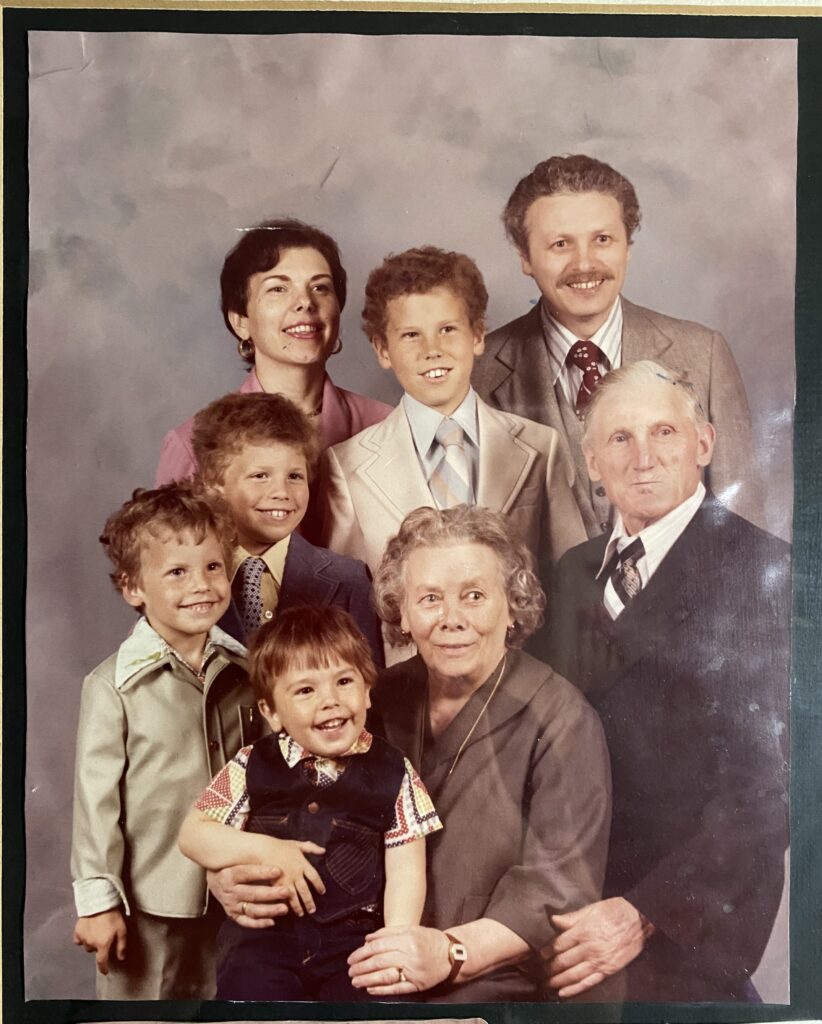

When the former New Brunswick scoutmaster Miklós Schlóder was greeted on the 70th anniversary of forming Boy Scout Troop 5, the celebrant recalled that he participated in the second scout camp organized in Bavaria in 1950 by the Hungarian scouts who had fled to the West from the Soviet occupation of Hungary. He confessed that somebody else from the audience also attended that camp. He didn’t reveal her name, but the audience immediately recognized and greeted Eva Kazella. I didn’t know at the time her family had also been deported. After nearly ten years of European ‘adventures’, she arrived in the United States with her mother, where the next stage of her life began, with a 1956 refugee husband, four sons and 13 grandchildren, as well as a strong friendship with the Püski family, the literary evenings held in their house and the ITT-OTT gatherings.

***

Why was your family deported?

When my father was born, in 1898, Dévény was part of Hungary, as it had been for a millennium prior to World War I. After the Treaty of Trianon in 1920, it was annexed to Czechoslovakia as Devín, so when my brother Béla was born in 1933, he was a Slovak citizen. In 1938 it was annexed to Germany (by that time Austria had become part of the ‘Gross-Deutsches Reich’) and renamed as Theben. I was born there in 1940. When the war was over, it changed its name back to Devín and became part of Czechoslovakia again.

All Hungarian and German inhabitants were deported so that Slovaks could move in. We were evicted from our home in 1946.

Previously my mother had packed six times since ships were leaving for Vienna where we had relatives. Unfortunately, my father refused to leave. He said, we would not have to worry since our name was Suchy. He was wrong…When deportation started, we had to leave our home within half an hour…

In the early ’90s my husband and I went to visit Devín once. Before the war, it was a very charming, even elegant little town, where wealthy Viennese spent the summer. It looked terrible at the time of our visit. We wanted to take a photo of my grandfather’s grave in the cemetery, but the guards tried to take away our camera. They took away our passports, which we only got back later. In my childhood, we had two houses, one of which we lived in and the other we rented out. Our home had been demolished; the other was still standing, but in poor condition.

What memories can you recall from the years following the deportation?

We spent six weeks in a refugee camp near Pozsonyligetfalu (Petržalka, Bratislava) because I became seriously ill. Then we had to choose between Hungary or Germany. My mother didn’t want to go to Hungary because the occupying Russian forces were there. Ultimately, we could only go to East Germany, at that time also under Russian occupation. We were crammed into wagons like the ones used to deport the Jews a few years earlier. It was horrible! They took us to the Baltic Sea and put us in a camp. My parents were able to purchase train tickets to Thuringia. I still remember the terrible sights of the bombed-out Dresden and Berlin…From Thuringia my father escaped to Bavaria, where he worked as a boat man. He visited us from time to time to bring us food, because there was nothing to eat in Thuringia. I remember going with my mother into the forest to pick berries and mushrooms. Once we sneaked onto a farmer’s field to pick potatoes, but unfortunately, he chased us away. My 13-year-old brother once had the courage to walk through the woods by himself, take the train to Regensburg (to our father) and bring us food. This would be unthinkable today, but we had to avoid starvation. We lived in a very cold apartment with many windows and only a small round stove. I remember sitting so close to it with my plastic doll that its face started to melt…My mother was afraid we would freeze in the winter; she wanted to leave. Since our village was surrounded by occupying Russian forces, she sent me ahead with my brother. We told them that we were going for potatoes and the Russian soldiers let us through the checkpoint. My mom followed us with another family, telling the Russians that her children were waiting for her. Thank God, they were let through, too…

How long did you live in Germany? Did you speak the language?

For ten years. After a while we got an apartment with a kitchen and a room in a block of old barracks. This was wonderful since at the time a lot of refugees, called ‘displaced persons’ (‘DPs’) were living in Regensburg and the defunct and now empty Messerschmitt factory provided housing for them in large halls, up to thirty or forty people in a single room with only blankets separating them.

Everybody in Theben spoke Hungarian and German with an Austrian dialect. My father spoke Slovak, too. My mother had moved there from Budapest and always spoke to us in Hungarian, but for a long time I only answered her in German. When some Russian soldiers were lodging in our house, my mother told me that the Russians didn’t like the Germans. Only then did I start to speak Hungarian. My brother considered himself German. We went to school in Germany, but I didn’t speak the Bavarian dialect and the locals didn’t like my ‘Hochdeutsch’ either…

Once a week I attended the Hungarian School, and I also became a Hungarian girl scout. I attended quite a few Hungarian scout camps while living there, where I met for example Gábor Bodnár, later the chairman of the Hungarian Scouting Association in Exteris (KMCSSZ in Hungarian). When I returned from my last scout camp, my mother said: we are emigrating to the U.S. In the meantime, my parents divorced. My brother started to work in a coal mine in Duisburg, Germany and later moved to Johannesburg, South Africa to work in a gold mine and to attend university.

How were your first years in the United States?

My mother and I arrived in New York on September 8, 1956. The sponsoring International Refugee Committee (IRC) took us to a hotel. One of my mother’s old friends, who lived in the heart of Yorkville, the Hungarian quarter of Manhattan, told us that there was a vacant furnished apartment across the street, so we moved in. The IRC also got my mother a job in a cookie factory. We registered at St. Stephen’s Catholic Church, where Father Slezák informed us about the Friday choir rehearsals for Radio Word of Faith (Hit Szava Rádió Énekkara in Hungarian). Viktor Fischer, later Hungarian scoutmaster in New York, invited me to join the scouts, where I immediately made friends and felt at home. It was much better than in Germany. At the choir rehearsals I met several other Hungarians who became my lifetime friends. I joined a school run by Dominican nuns, but I regretted it afterwards: when I graduated, I got a job at a firm in downtown Manhattan, but I didn’t have a high school degree, so I had to go to evening high school after work.

The news of the ‘56 revolution had reached you in New York...

We went to protest in front of the UN building. When András Ludányi threw red paint at the Russian consulate, he was taken to prison, but was eventually released. Later, he tried to cut the Russian flag off the Coliseum building but fell and suffered serious injuries. When I visited him in the hospital, I told the policemen outside his hospital room that I was his cousin, so they let me in. At that time, there were a few Hungarian radio stations in New York with Ferenc Koréh, Gyula Appatini and László Kálmán as commentators. László was a very good friend of ours. When he announced that Ceaușescu was in New York,

there were so many of us protesting that the Romanian dictator didn’t dare to go back to his hotel from his meetings.

László organized lots of Hungarian demonstrations in New York, also at the Romanian Consulate. Upon his urging we planned bus trips to the Capitol in Washington DC, to protest for the release of Miklós Duray, Hungarian writer from Slovakia. The radio often played Transylvanian-themed songs banned in Hungary.

The St. Imre Club was also nearby, frequented by many young Hungarians at the time. Is that where you met your husband? How did he come to America?

Ignác Kazella, a.k.a. Iggy grew up in Tát near Esztergom, Hungary. Because of his ‘kulák’ parents (the Russian term ‘Kulak’ was coined by the Communists to label somewhat wealthier farmers, who were discriminated against, persecuted and ultimately stripped of their property by the government), he was taken to a forced labor camp for two years and released only after Stalin’s death in 1953. He was unable to attend university and worked in a coal mine under very tough conditions. He took an active part in the 1956 revolution and therefore had to leave Hungary when the revolution was crushed.

He left with a few bottles of pálinka on his bicycle. When he was stopped by Russian soldiers, he gave them some bottles to take him to Győr, which was surrounded by the Soviets so he couldn’t have gotten there otherwise. From there he took a train to the border and then walked with others over to Austria. He arrived at Camp Kilmer in the early January of ’57, aged 23. There he signed up for a six-week English language course with other friends and Father Iván Csete. Later Iggy got a scholarship to Dartmouth University and started to study medicine. During summers, he came to New Jersey to work, as the scholarship was not enough to cover his cost of living. He started working at a country club with a friend, first as a dishwasher, next year as a busboy, and by the third summer they were waiters. After an accident with his newly bought car, he had to start working in New Jersey and studied at Fairleigh Dickinson University, changing his major from medicine to engineering.

How did the two of you meet and get married?

We had met several times, probably for the first time at the so-called Hungarian Pöttyös Ball. I had changed jobs as I wanted to join an airline company so I could travel. With Lufthansa, I visited my uncle and aunt in Caracas, Venezuela, where my aunt founded and oversaw the Hungarian kindergarten. When I travelled back from there, Iggy picked me up at the airport. He said that he was unable to work, study and court me at the same time, so he was just going to propose…I said yes since I was really trying to get away from home by that time. We got engaged in April and married in July 1961. We settled in New Jersey. After recuperating from an injury suffered at work, Iggy got hired by Unilever and had to start studying chemistry instead of engineering, which the company paid for. Our first two sons, István and Károly were born in 1969 and 1970, respectively. I was on maternity leave for only three months. The kids were looked after by an au pair. After getting his chemistry degree, Iggy enrolled at Fairleigh Dickinson Dental School and worked as a dentist for many decades. We worked in the same offices, a mile from our house in North Haledon. Péter and András were born there, in 1975 and 1976, respectively.

To what extent did you live a Hungarian life?

We spoke Hungarian at home, even with the dog, so that the children could speak Hungarian. They went to Hungarian schools on Saturdays and Hungarian scouting on Thursdays to Garfield, New Jersey. They loved it and had many friends from there to this day. In the mid ’80s, István and Károly went to the same Franciscan High School in Esztergom, Hungary where their father had studied before. One day, when Russian soldiers were passing by their building, the boys shouted out of the window: ‘Russians, go home!’ They heard this many times on László Kálmán’s radio. Father Pál Rácz was almost dismissed because of this incident, the boys were not allowed to enter Hungary the following year. As far as I know, even a Hungarian Communist propaganda movie was made about it. We often visited Hungary and met relatives there. I don’t remember my first trip to Hungary but recall the adventures. Once I flew to Vienna and took the train to Budapest. At the Austrian–Hungarian border at Hegyeshalom, the police searched my suitcase listing everything that I brought with me, including a radio for my brother-in-law. On the way back they noticed it wasn’t there. When asked about it, I replied that I had lost it. Meanwhile, of course, I was very afraid that something would happen to me…

Were you involved in the Hungarian American community’s life?

We of course helped the Hungarian scouts and went to Sunday masses at the St. Stephen’s Church in Passaic or the St. Ladislaus Church in New Brunswick, both in New Jersey. We organized a lot of literary evenings in our house with publisher Sándor Püski’s help, who lived in New York. We invited all the people we knew for these events, even from other states. For example, Balázs and Csilla Somogyi, Nusi and Tibor Cseh came over.

Many famous Hungarian poets and writers from Hungary and Transylvania visited us in the ’70s and ’80s, such as András Sütő, Sándor Kányádi,

Mihály Czine, Julcsi and Sándor Csoóri, Böbe and Győző Hajdú, the editor of Igaz Szó. They typically started their North American visit at New York, then at our place, before they went to the Bőjtös family in Cleveland, Ohio and to the Sass family in Chicago, Illinois. Many people attacked us for this, as they mistakenly thought that those who came from Hungary were all communists…

The same was assumed about the quests of the ITT-OTT (Here-there) gatherings, which you also visited regularly…

The first gathering was at the Magyar Tanya in Pennsylvania in the late ’60s. We attended the second on the shores of Lake Chautauqua in New York, together with the Somogyi, Ludányi, Éltető, Bőjtös and Sass families. When that place burned down, the camp moved to its present venue at Lake Hope, Ohio. Our kids loved it very much, they waited for it all year. We didn’t give lectures, but we were always present and supported the organizers. My husband also helped them as a doctor. On the 12-hour-long way back home, we always sang Hungarian songs in the car.

Have you ever thought about moving back to Hungary?

We had plans to move back upon retirement. Two of my friends did, because with the pensions we had here we could live very well in Hungary. We sold the dental practice in 2010, but then Iggy got Alzheimer’s. He died in 2013 and was buried in Hungary, but all my sons and grandchildren live here in the U.S.

You said your brother considered himself German. What about you?

I always considered myself Hungarian… I’ve recently received Hungarian citizenship. It wasn’t a straightforward process, but I’m very proud of being a Hungarian citizen.

Read more Diaspora interviews: