Edith K. Lauer witnessed the tumultuous events of the 1956 revolution and freedom fight as a 14-year-old from the balcony of their family home overlooking the Zsigmond Móricz Circus, one of the prominent locations of the fighting against Soviet tanks. Her entire family was involved: her mother worked at the local pharmacy dispensing medications and helping wounded freedom fighters; her father was a member of the Revolutionary Committee of the Hungarian National Bank; she, her sister Nóra and her grandfather worked side-by-side building barricades in the square as well as gathering supplies from the pharmacy to help classmates prepare Molotov cocktails. They escaped in two waves in November 1956, and after being reunited in Vienna, eventually headed for the United States 1957. In 1963, Edith married John Lauer, an American, and they started their common life in South Texas. In 1991, she was one of the founders and the first president of the Hungarian American Coalition (HAC). She currently serves as Chair Emerita of the largest umbrella organization of Hungarian Americans; at 81, she remains active in the Hungarian American community.

***

What were your most life-changing memories of the 1956 Hungarian revolution and freedom fight?

The totally unexpected outbreak of the revolution! After leaving school on the morning of 23 October, the first day of the revolution, I never went back to the school or saw my friends and classmates again. Overnight, my entire life—and also my family’s life—changed dramatically. I was only 14, but because I was an eyewitness, I saw and understood what was happening. I spent hours with my sister lying on the balcony and looking down onto the streets, observing trucks carrying injured or dead people. And right around the corner was the pharmacy where my mother worked. She was involved from the very first moments almost around the clock. My 17-year-old sister, Nóra and I were following the events in the company of our grandparents. My father mostly spent those days at his workplace as a member of the Revolutionary Committee of the Hungarian National Bank. My mother was busy in the pharmacy treating injured freedomfighters. The last thing they wanted was to have two teenagers roaming the streets when anything could happen. So, we were strictly forbidden to leave our apartment. Of course, we did not obey.

But you did not get into trouble, did you?

No, we only helped build barricades. This was our most active participation in the events. Somebody entered our apartment building—there were dozens of apartments

in it—and started shouting that people were needed to lift the heavy cobblestones to block the street, where the tanks were expected to enter the square. On 23 October, I also participated in the demonstrations, marching from the Bem statue to the Parliament. And so did Nóra, but we were there separately. Instead of getting home from school at 4 p.m. as usual, we arrived only at 10 p.m. and to our surprise, our parents did not scold us. They were too busy trying to listen to Radio Free Europe, because obviously, the Hungarian communist radio was not disseminating any reliable information about the events of that day.

In the following days, I witnessed the bravery, desire for freedom, the unity as well as the purity of spirit of the Revolution.

Some examples that I will never forget were the store shelves left untouched in broken shop windows, the boxes put out to collect money for the freedom fighters and the families of the victims, and farmers bringing fresh food from the countryside to Budapest. I also saw corpses of freedom fighters laid out on Móricz Zsigmond Circus and the accidental fall and horrific death of a young man who tried to tear down the red star—the hated symbol of communism—from a government building opposite our home. These images have never left me.

You mentioned in your Memory Project interview that the two biggest lessons of the freedom fight were that everything is possible and that it was the Hungarian revolution that revealed for the first time the true face of communism to the world.

Yes, everything seemed to be possible for 13 days. Suddenly, people were brave enough to say exactly what they thought. The free radio reported the release of political prisoners, including of Cardinal Mindszenty; and one day, an old bridge partner of my father’s who had disappeared years before knocked at our door. I remember the crowds on the street singing, and standing in line to take turns to read the free newspapers glued to the wall. Although the revolution was brutally defeated, it was ultimately successful as the first nail in the coffin of communism, because it eventually led to the fall of the communist system in 1989.

As for the second lesson, in countries like France and Italy there were active and popular Communist parties in the ’50s, but

their view of communism was based on Soviet propaganda, until the Hungarian revolution revealed that it was an oppressive dictatorship.

When hundreds of thousands of ecstatic people marched on the streets, sang the same patriotic songs, chanted ‘Russians, go home!’ and loudly expressed their shared hatred for the communist system, even former sympathizers had to believe them. The Hungarian revolution was the fiercest and most violent expression of opposition within the Soviet block. There were so many people deeply affected even outside Hungary. Let me mention just one: an American student in Paris, Lee Edwards, joined the demonstrations organized on behalf of the Hungarian uprising; similar demonstrations were held in other Western capitals as well. He later became the founder of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation (VOCMF) in Washington, DC. He is 90 years old now and I have the privilege of calling him a dear friend, and together we serve on the board of VOCMF. That is a motivation I admire: only hearing about the Hungarian revolution led him to a lifelong commitment to helping reveal and fight the evils of communism.

Do you think the world paid any (or enough) attention to the revolution at that time? The United States failed to help the freedom fighters.

I was always curious about that, so once the material became available, I researched that very question in preparation for a 1956 commemorative speech I gave in Cleveland. I think if the revolution had taken place in one of the subsequent decades, maybe the decision would have been different. But at that time President Eisenhower was at the end of his re-election campaign: the presidential election took place that year on 6 November. John Foster Dulles, then Secretary of State, advised Eisenhower that it was simply too costly to intervene. Accordingly, he sent a message to Khrushchev, the Soviet dictator at that time, stating that the US had no intention of intervening in the Soviet sphere of influence, which included Hungary. This meant that the Soviet Union did not need to worry about any US threat if they crushed the Hungarian revolution.

Your parents’ decision to leave Hungary must have been very hard as they loved their homeland very much. Do you have any personal memories related to their decision?

In those days children were to be seen, but not heard! But, at the same time we were aware of the discussions in our own family and saw many relatives who came to our apartment to say goodbye before their own escape to the West. My father’s brother and his family came first. My mother’s half-sister with three small children were next. Ultimately, all of them ended up in the Washington, DC area, where we lived close to each other for many years. At this time, we were living in the same apartment with my grandparents, who said all along that they were too old for such a journey and would never leave. Can you imagine that? Their two daughters and five grandchildren were about to emigrate and they really had no way of knowing if they would ever see them again or if their beloved family members would be successful in their escape to the West.

After getting married and moving to Texas you had a 100 per cent American life. Did you like it?

Yes. I was very excited about living an American life. I was extremely proud when people said they had no idea that I was a foreigner, because I had no discernible accent. What I did not like were the frequent moves—New York, Connecticut, Belgium, Kentucky, Texas, New Jersey, Ohio—as John advanced professionally. The moves required that we pack up the house, move across the country, set up another house, find schools for the girls, make a new set of friends and become active in a new community. It wasn’t easy, but looking back now, I learned so much in the process and grew stronger and more independent.

Years later, I heard about a young man, László Hámos, and his organization, the Hungarian Human Rights Foundation (HHRF), whose mission was to call the attention of US policymakers to the plight of Hungarians living as minorities in the region. This was our first involvement in the Hungarian American community. Until that time, I had volunteered for many American organizations and over the years, I learned how to establish and run a non-profit organization, to set up a board of directors, committees, etc. Although I didn’t realize it, that was my training process, which later was put to good use in the Hungarian American community.

You still managed to maintain your dual identity so well that you now feel at home in both countries. You became the first president of HAC and got involved (with your daughter, Andrea) in several other 1956-related projects. What happened in the meantime?

History happened in the meantime: 1989 to be exact, when communism unexpectedly collapsed in Hungary and across the region, and that’s when I became involved in the fundraiser for HHRF. Let me backtrack and talk a little bit about our family. At home we spoke English, but both of our girls knew ‘kitchen Hungarian,’ and we travelled to Hungary every two years or so to get them familiar with their heritage and meet their relatives. In 1990, Andrea graduated from Lehigh University with a degree in journalism, and decided to move to Hungary. This was a heady time: the wall came down and democracy would soon return to Hungary. She lived there for nearly six years, worked hard at learning Hungarian, discovered her love for Hungary and her 56er roots.

While being a proud American, I have always remained very proud of my Hungarian identity.

My family, especially my grandfather, definitely played a big role in this. He was a brilliant man from the famous Kozma family: which included actors, poets, a president of the Hungarian Radio, and others. He was highly educated in history and literature. When we were children, he often told us stories about how Hungarians prevailed even in the worst of times. He regaled us with examples of how talented Hungarians are, how many have won Nobel Prizes. Even after the devastation of WWI, WWII and 40 years of communism, Hungarian accomplishments in the fields of art, science and sports have been remarkable. He also recited Shakespearean poems in Hungarian and of course, lots of Hungarian poems, too. No wonder I ended up majoring in literature; he indirectly pushed me in that direction. Because of his pride in being Hungarian, I never had the feeling of ‘a poor little country, oppressed by the big Soviet Union that could not fight for itself.’

You also said in the interview that in the US you see the world through a Hungarian lens, while in Hungary you see it through an American lens. Can you give us some examples?

While establishing the Coalition in the early 1990s, I often tried to look at issues through the ‘other lens’. If something works in the US, why not try it in Hungary? And if it works in Hungary, why not try it in the US? There are a few examples of this. One of the first major projects of the Coalition was advocating for NATO expansion to include Hungary. One of the important steps in this process was to hold American-style town hall meetings in several Hungarian cities to acquaint Hungarian voters with the advantages and responsibilities of NATO membership. Afterwards, Hungarian voters overwhelmingly supported NATO membership. We also organized customized programs that brought a group of Hungarian mayors and later, secondary school directors to the US to observe the best practices of their American counterparts and share their own experiences.

And thus your dual identity and thinking enriched not only you but also your environment.

Exactly. We always had a large circle of friends in the various places where we lived. And quite often I would take friends to Hungary; Americans who would have never gone there on their own. I tried to show them the Hungary I knew. I took them to the Parliament, not only for a tour, but also for special lectures or programmes. We also took a few of them to Transylvania, which was an unbelievable experience. On one memorable visit, John, Andrea and I inadvertently found ourselves in Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca. Romania) when a demonstration broke out protesting the limitation of Hungarian language instruction in Hungarian schools. Of course, Andrea and I wanted to stay, but John, as the president of a large US company, had been urged to travel to Romania only with bodyguards. He had declined. When he mentioned this to the late Bishop Kálmán Csiha who we have became good friends with, his response was: ‘My dear John, you must not worry, you have the best possible bodyguard: God!’

Was this enough for him?

Yes! He was always very supportive and loved our many subsequent trips to Transylvania. He understood and supported another major campaign: when we tried to clarify the ownership of the Kolozsvár Collegium, which was founded 450 years ago, but the Romanian authorities refused to return it to its rightful Hungarian owners. Fortunately, I was able to develop a good relationship with an official in the US Embassy in Bucharest and kept sending him pictures and information about the continued harassment the displaced Hungarian students were having to endure. ‘How is this possible in a supposed democracy? How would you feel if your child faced this situation?’, I asked him. He advised me that this might be a good time to inform Romanian President Iliescu about these legal challenges. I managed to get the President’s direct fax number and in a period of 48 hours, we flooded him with 30-40 letters written by Hungarian Americans demanding the return of the Collegium building to its rightful owner, the Hungarian Reformed Church. To our delight, during the Christmas holiday in 2002, the school head, Árpád Székely, received a notice stating that the Collegium building could be reopened as a Hungarian school in January.

Turning to your Coalition, please tell the short story of the foundation to our readers. How did it start?

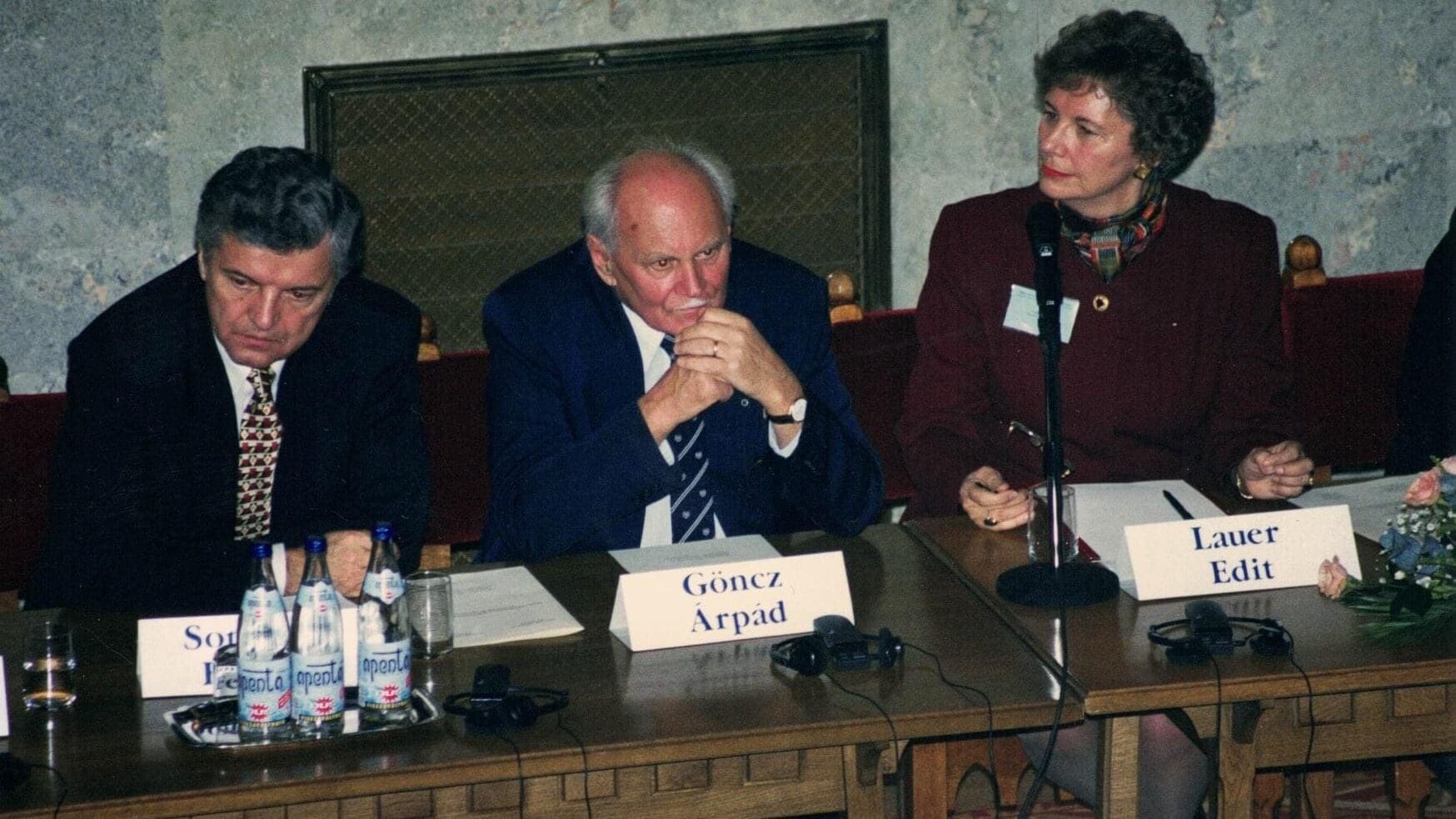

I often say that the stars were aligned! Just after I had met and worked with so many community leaders, we had a historic opportunity to build important bridges between our two countries. A small group of Washington area Hungarian Americans got together to discuss how best to help Hungary benefit from US programmes and scholarships established to aid post-Communist countries. At that time, there was no viable Hungarian American organization to take on this important role. So, 15 organizations and five individuals, myself included, formed the Hungarian American Coalition, based on the philosophy that we could accomplish more if we all worked together than we ever could on our own. To my surprise, I was elected to be the first president and would go on to serve for the next 12 years.

Andrea is now the President and you are Chair Emerita of HAC. Are you still active?

Andrea has served as President since the end of 2016. She has all the talents she needs: she is a wonderful organizer, speaker, a talented journalist and an unbelievably hard worker. I am extremely proud of her. One big difference between the two of us is that I started my work after our children had grown up, while she is very active while being the mother of two young boys.

I remain active in HAC, but more as an advisor in the background.

I am actively involved on the Boards of the VOCMF and in the Hungary Foundation, a major supporter of Coalition projects. One area where I try to provide guidance to all of these organizations is fundraising. An important rule that I follow is that if you ask someone for money, but you have not given any, it is very easy for the other to say no. When I ask people for support, I first tell them of my own contribution and ask them to follow my example. I think that comes across, which is why I am a pretty successful fundraiser. Since the beginning of HAC, we have had to raise the funds for every project we undertake, but we plan to start an endowment this year that will assist us in our long-term planning.