I met Anna at the 2023 Hungarian Congress in Cleveland, OH where her latest documentary was screened. However, I only learned about her adventurous personal and professional life a year later, when I visited and interviewed her; not only about her 96-year-old 56er father, but also about her adventures in the former Soviet Union as a university student during the regime change, then in Africa with her family, her travels to Transylvania, her involvement in the 1956 Memorial Oral History Project, and her future plans.

***

Your father came to Canada as a refugee during the 1956 revolution, yet found a wife in Hungary 10 years later.

My father was born in 1929 in Nyírbéltek, a small village in the Nyírség region of Hungary. He was the first person in his family to attend university. When the revolution broke out in 1956, he was working as an engineer in Budapest, and though he is not the adventurous type and had no desire to leave his homeland, he fled when he saw the uprising being crushed. He’s spoken to me about what the demonstrations in Budapest were like; how the power of the crowd moved him, but at the same time he feared that things wouldn’t end well. In the early days of the uprising, one of the first things employees did was break open the filing cabinets that held their personnel files. In those files my father discovered that his parents had been labelled ‘kulaks’ [a Russian term for a wealthy peasant], which meant that he’d have no future in communist Hungary.

Armed with a fake document giving him permission to visit a factory near the Austrian border, my father fled Hungary with two friends. From Austria he went to Wales, where he spent a few months learning English, and from there immigrated to Canada. Ten years later, when the Hungarian state granted amnesty to those who had left in 1956, he was able to return to Hungary to visit his parents, who by then had moved to Debrecen. This is where he met my mother, a young woman who lived across the street from his parents. He was so taken with her that he came to visit again the following year and married her.

My mother was born in 1943 in Subotica, Serbia (Szabadka). Her family had their own difficulties. Despite the fact that my grandfather, a dentist, was serving with the Partisan Army at the time, the authorities decided to deport his wife and children, simply because they were ethnic Hungarians. My grandmother and her four daughters were at the train station, when at the last minute an influential friend interceded on their behalf, and they were granted permission to stay. Shaken by these events, the family fled to Hungary shortly after, first to Békéscsaba, then to Debrecen, where my mother went to school and became a math and physics teacher. After their wedding in Debrecen, my father returned to Canada, but my mother had to wait nine months before she obtained permission from the Hungarian government to join her husband. They barely knew each other when they married, yet they’ve been together, happily, ever since.

What did your mother do in Canada?

When my mother first arrived in Canada, she didn’t speak English. I was born a year later, and my brother was born two years later. She stayed home to raise us but she later taught high school math. For 40 years she was also a heritage language school teacher on Saturdays at the Arany János Hungarian School.

Since the 1930s, Toronto already had a Hungarian heritage language school operating at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Roman Catholic Church, but given the influx of Hungarians following the 1956 revolution, there was demand to open a second school. In 1972, the Hungarian community purchased a bigger community center, which housed the Arany János school. In its first year the school had a Saturday afternoon program called Family Circle (Családi Kör), where parents could bring their kids for arts and crafts and other activities. As a child, I learned to embroider and crochet. There was a gym too, where we’d play basketball. The following year formal lessons began in Hungarian language, literature, history and geography. After school, there was an option to stay for Family Circle. Hungarian folk traditions were very important for school founders Tamás and Elizabeth Balogh; music and folk dancing were included in the curriculum. I attended this school as did my two sons years later. As an adult I helped my mother, especially with the school plays. The school still exists at the Hungarian Canadian Cultural Centre, which reopened in a new location about ten years ago.

You were and still are a member of the Kodály Ensemble.

Vera Nacsa introduced us to folk dance at the Arany János school. I loved it immediately. When I was 14, I joined the Kodály folk dance ensemble and danced until I finished high school. Gábor Dobi, a friend of mine from Arany János, who also joined the Kodály Ensemble at the same time, remained an active member. I later accompanied him on trips to Transylvania and Moldavia (Romania), where we went to witness and record folk traditions still being practiced in ethnic Hungarian villages. About ten years ago, Gábor started the alumni branch of the Kodály Ensemble, where former dancers can be together again. Unlike the younger Kodály dancers, this is not performance based, we simply get together to improve our dancing skills for the fun of it. Since then, in response to demand, he also started a very successful adult beginners’ group.

Tell us more about your trips to Transylvania and the documentary.

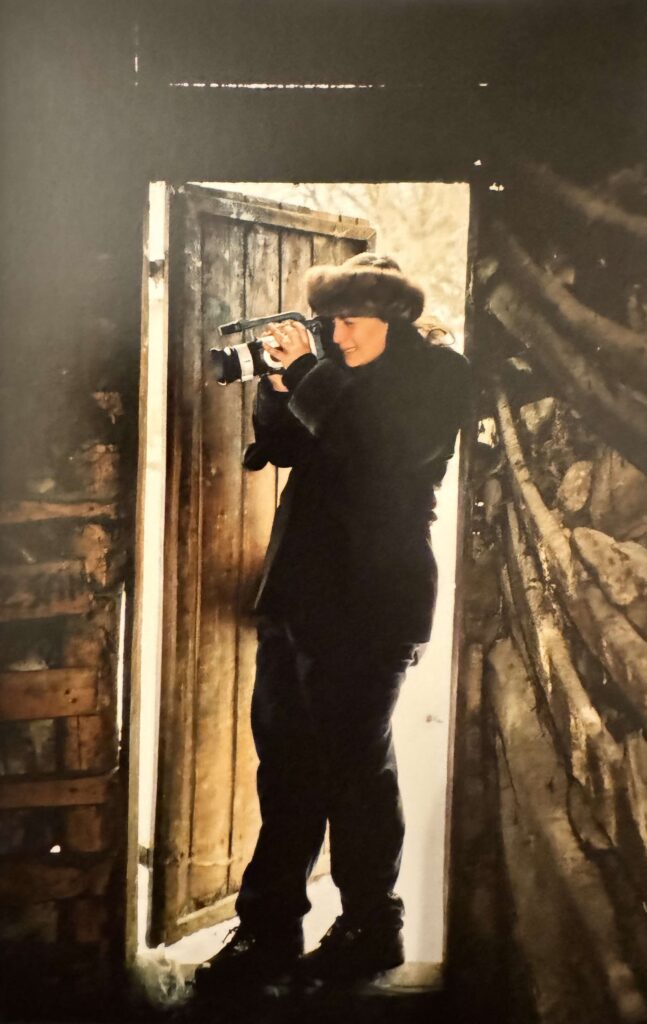

After I got married, my husband and I moved to Africa. When we returned four years later, I noticed an invitation at my parents’ house for an event organized by Gábor Dobi at the Paraméter Club (founded by local Hungarian language radio host Zsolt Bede-Fazekas) featuring Csángó folk songs, music and dancing. I hadn’t been active in the Hungarian community for years and this event pulled me back in. The young performers were fantastic. At the end of the show they told the audience that they were raising money to buy a video camera, so they could record quickly disappearing Christmas folk traditions among the Csángó peoples in Transylvania and Moldavia. After nearly four years of pursuing his dreams in Africa, my husband agreed it was my turn. We purchased the video camera and I ended up accompanying the small but enthusiastic group to Romania. I remember frantically studying the instruction manual for the camera on the plane. This is basically how my career in documentary films started.

We spent Christmas in Lunca de Jos (Gyimesközéplok), a village in the eastern Carpathian mountains and witnessed the Csángó people’s seasonal traditions. We met local musicians and took part in festivities, all of which involved going to other people’s houses, dancing, singing, drinking pálinka and eating delicious food. For this of course we had to first slaughter a pig, which was an experience in itself. The highlight of the trip was celebrating New Year’s Eve in a small village in Moldavia called Fundu Răcăciuni (Külsőrekecsin). Here we witnessed a tradition called urálás, which involved the local villagers dressing up in costumes and prompting a large goat puppet to dance. In quieter moments we learned beautiful songs from the locals as we peeled potatoes together. I’m fortunate to have witnessed these traditions first hand. Many years later in 2017 we traveled to Sic (Szék) in Transylvania, this time to record more well-known folk customs during the Easter season.

What did you study at university and do before filming?

I studied history at the University of Toronto, and then obtained a master’s degree in Russian and Eastern European Studies, just as the Soviet Union was falling apart. I’ve always been very interested in history, particularly Hungarian history, but I realized that Hungarian history cannot be understood without also understanding the histories of the great powers surrounding it: Germans on one side and Russians on the other. And so I learned German and Russian, and lived for a while in both countries. It’s interesting that I never actually lived in Hungary, perhaps because I thought I could go there anytime…

How did you end up in Germany and Russia?

When I was in high school, I was an exchange student in Berlin, then worked as a translator for an insurance company in Hannover. Had I not been invited to Moscow, I would have worked there after university. A university classmate, who was there when the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, invited me to visit him. I went there in January 1992, originally for two weeks because I had a job waiting for me in Germany, but the excitement of perestroika enticed me and I stayed until September and learned Russian. In September I started a two-year master’s program back in Canada, which gave me the chance to return to Moscow through a student work program. I traveled back in the summer of 93, extending that stint as well, staying again for a few months.

What were you doing there for that long at the age of 22?

Besides studying Russian, I had a small job at the Canadian Embassy. A friend and I bought a car. We traveled a lot, making several trips to the Baltic countries. Our big final trip was from Moscow to Crimea and from there through Ukraine to Hungary. When I came back a second time, I worked for a British bank, Barclays, which was very exciting given the enormous economic changes at the time. I also had a chance to travel to Kyrgyzstan, where I worked as an interpreter for a filmmaker who wanted to make a documentary about wild yaks. We never did find the yaks but the experience was unforgettable. Then I came back to Canada and finished my degree.

When did you meet your husband and how did you end up in Africa?

I met him at university and as soon as I finished my master’s degree, we got married and moved to Uganda. This was his dream. He had studied mathematics, but has always had an entrepreneurial bent and a desire to start something new. Uganda appealed to him because they speak English there, and because he sensed that there would be good business opportunities as the country was beginning to recover after the civil war. He ended up starting a business procuring good quality maize for the World Food Program. We originally went for a year, but somehow it turned into four… At the beginning I helped him with the business until I became pregnant. After my son was born, I worked for a geological company, writing a few chapters in a guide on how to do business in Uganda. These chapters provided information on the political and economic climate as well as on taxation and how to obtain licenses. I recall feeling fortunate to be leading such an adventurous life as a young woman.

You mentioned that those four years in Africa were difficult for you. Why?

Malaria remains a leading cause of death for babies and young children in Uganda and this was always on my mind. My husband contracted malaria on three occasions; one case in particular was quite severe. I was worried not only about him, but also about our little boy. On the way to town you could see the carpenters selling their wares on the side of the road; first you’d see the tables and chairs, then the regular coffins, then the tiny coffins….

Back to filming: did you continue making films between the two trips to Transylvania? Why did you end up becoming an editor?

Our trip to Transylvania was a defining point in my career. It was while I was editing the footage we shot during this trip that I realized how much I love editing. Since then I’ve worked on feature films, documentaries and news reports as an assistant editor and editor. In the meantime, my own material featuring the Hungarian community in Canada as well as Hungarian folk traditions have appeared on Duna TV, Hungary as well as the local Hungarian TV program. I also did a report on horseback archery for CNN.

Finally, tell us about your involvement with the 1956 Memorial Oral History Project.

The events of 1956 have always been in my mind, partly because of my father’s story but also because of my love of history. As we approached the 50th anniversary, I knew it was time to record these stories and interviews. At first I thought of doing this through the University of Toronto, but in the end it was the Rákóczi Foundation that made the project possible. The interviews were housed in the archives of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario, which specializes in preserving the immigrant history of Canada, but I was pleased that several years later a copy of the materials were transferred to the Széchenyi Library in Budapest; they are perhaps more accessible to international scholars.

How did the collection work itself take place?

We put out a call for volunteers to interview people who came to Toronto following the 1956 uprising. 15–20 volunteers from across Canada, primarily Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta conducted 100–120 interviews. Most of the interviews were recorded with an audio recorder, but there are some video recordings as well. Many subjects supplemented the interviews with personal photos, drawings and other documents. Another part of the project dealt with free form submissions from 56ers, which included memoirs and poetry. We featured these interviews, photographs and documents in an exhibition we put together to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1956 revolution. It was shown in several places, including Toronto City Hall. I have a lovely photograph of my father and my son at this exhibition. They are looking at a photograph of my father and a group of fellow refugees in Wales linking hands and pretending to build a bridge to Canada while waiting to be transported there. 10 years later, for the 60th anniversary, the Rákóczi Foundation continued the project, and I conducted another few interviews as part of this effort.

Which was the most memorable and special conversation for you?

There is one story that I’ll never forget. A newly married couple was walking through a field to the Austrian border. The husband went first, his bride of just one day a few steps behind so that if he stepped on a landmine, she at least would be safe. However, when she tripped over a piece of barbed wire and fell, they were deeply shaken. They decided to continue their walk hand in hand: if a mine blew up, they would die together.

The 70th anniversary is coming up soon. Do you have any related plans?

There are still a few 56ers who should be interviewed. I’d also like to make interviews with Transylvanians living in Toronto who took part in the Romanian Revolution of 1989, alongside Pastor László Tőkés in Timisoara (Temesvár). To my knowledge, no one has done this yet.

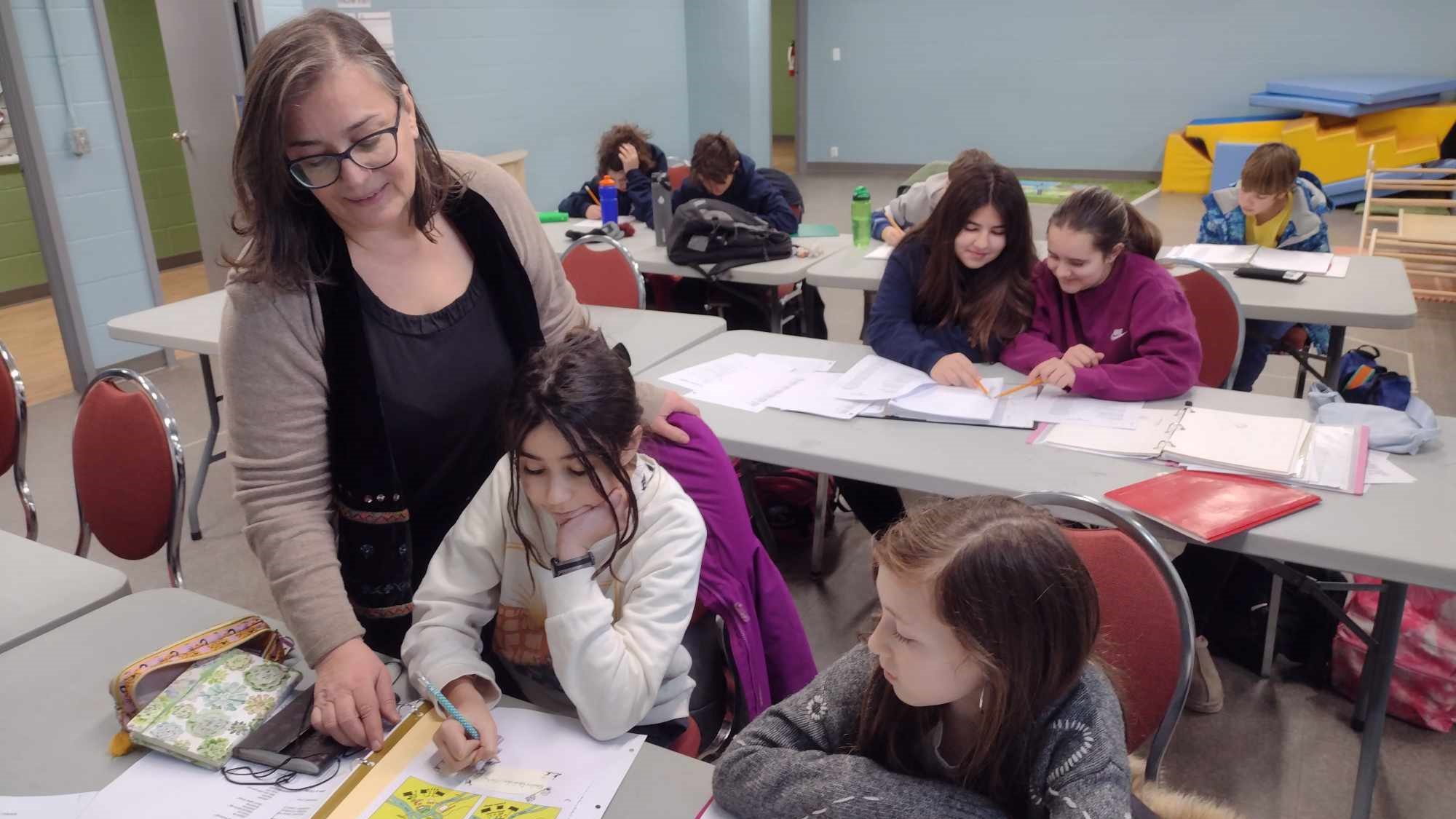

You now teach at St Elizabeth’s School. Do you pass on any of these interests to the children there?

It’s important to me that the kids know about their family history. One assignment I give my grade 6 class is to interview a family member who immigrated to Canada, and if that person is no longer alive, to interview someone who can tell them about this experience. The kids always learn something new, and so do I. A few months ago I asked my class where their grandparents or other relatives were when the events of 1956 unfolded. Seeing that most of the class is of Transylvanian heritage, I was not expecting much of a response. To my surprise a girl told me about her grandfather who was sentenced to seven years in prison because he expressed solidarity with the 56 freedom fighters by gathering with a group of like-minded youths in front of a monument of Sándor Petőfi in Sighisoara (Segesvár). I had no idea that the revolution in Hungary had such repercussions in Transylvania.

Do you also try to pass on folk traditions to them?

Yes, the Transylvanian trip has been a great source of inspiration for me and we referenced some of those traditions in our last Christmas performance. In the spring, we put together a folk fashion show, which was also very successful.

How do your sons feel about their Hungarian identity?

My husband and I are now separated, but I’m very grateful that when we were together, he always supported my volunteer efforts in the Hungarian community. And though he never learned to speak Hungarian, he didn’t feel excluded when I taught our sons to speak Hungarian. I know this isn’t the case in many families. My sons speak Hungarian very well and are an active part of the community. Thomas (16) dances with the Kodály folk dance ensemble, and Attila (27) has also recently returned, given that this is a special anniversary year for the group. When I go to alumni dance practice on Tuesday evenings, it’s a great feeling to see him there. Both my sons also attended Hungarian school on Saturdays, and took part in poetry recital competitions. They were particularly fond of reciting ballads by János Arany. This summer they went to Hungary together. The fact that they were there without me suggests that they do have attachment to their Hungarian roots. I’ve done my best to give them a solid foundation, now it’s up to them…

Read more Diaspora interviews: