I met Ferenc in Cleveland, Ohio at the Hungarian Congress in November 2023, where he helped his father with providing the technical background and then delivered a presentation about the Regös-tour to Hungary, Transylvania, and Moldavia. The interview with his father revealed how Ferenc experienced a childhood with three languages and cultures. I now asked the 22-year-old about how he serves local diaspora communities and how he tries to combine his parents’ cultural heritage with his studies and future career.

***

When did you decide that you wanted to continue your grandfather’s very rich cultural heritage?

Unfortunately, I never met my grandfather: he died in 1995 and I was born in 2002. His vast cultural heritage came to me through my father and my grandmother. I was in fifth grade when she passed away, but we always had a very close relationship; she held the family together. I started to get interested in my grandfather’s accomplishments in high school. That’s when I started to understand its importance and what it meant to me. That’s when I first looked at his papers, but I hadn’t read his writings in detail. I also heard a lot about him from my father. One of his greatest undertakings was the Hungarian Association, which at that time meant not only the annual Hungarian Congress, but much more: countless other Hungarian events and groups were organized, which unfortunately ceased to exist over the past decades. However, the Hungarian Congress is still being organized, in 2024 for the 63rd time. I’ve been attending it since I was one year old: my parents always brought me along. I was often the only child, just like my father used to be decades earlier. At these events I also heard a lot about my grandfather. So it wasn’t just one moment, but rather a process, having heard about him all my life, being always an example for me to follow…

When did you decide that you wanted to do something like him?

Until the end of high school, I wanted to be an engineer, but I realized that my mathematical talent was not as strong, and I started to become interested in international relations and history, especially family history. In my first or second year of high school, I started researching my grandfather’s family. I read the paper my grandfather wrote about our family history, I did some research on the internet about the Somogyi family, and asked my father to explain everything he knew about it. I started to feel more interested in another profession, and when I finally decided that I wanted to pursue relevant studies, I was very inspired by my father’s words: ‘You are stepping in your grandfather’s footsteps, following his example.’

I was also very impressed when we searched my grandmother’s house after she passed away and brought over my grandfather’s books and papers and started to sort them out. My father put the most important works on our shelves. Some of them are very valuable manuscripts and documents that my grandfather brought from Hungary when he had to flee at the end of World War II. This also helped me understand better what he was involved with, and although I couldn’t review all the documents in detail, later, during my university research, I managed to research some key documents. My grandfather wrote a history of the Hungarians in Cleveland, Ohio, in the 1970s and 1980s, providing not only facts, but also his worldviews. He also wrote a short piece on King St. Stephen and the Holy Crown.

What kind of academic research are you referring to?

A few years ago at Princeton University, I started researching Hungarians in Cleveland including the Hungarian Association for a longer research paper about them and their mission. That’s when I started reading the Hungarian Association’s Chronicles, which my grandfather and father had been writing and editing for many years.

And there was something else I forgot to mention previously. A few years ago my father contacted my grandfather’s family in Hungary. As my father has already told you, my grandfather’s first wife didn’t want to join him when he fled, so she stayed in Hungary with their four children. My father was born in America to his second wife. This summer my parents and I met all our relatives, but I already had met them a year earlier. Before the Regösök-tour to Hungary, Transylvania, and Moldavia, I contacted one of my cousins, and stayed with him for a few days, and after the tour I went back to him, and he drove me to Pécs, Hungary to meet the rest of the family there. My father had met them in the early 1990s, when he accompanied my grandfather to Hungary once, but unfortunately, he didn’t keep in touch with them later. He keeps telling me that I’m the connector, not him. I’m indeed on good terms with my cousin and his daughter of my age, as well as with other relatives. It was a great experience for me when in Pécs I saw photos of my grandfather and learned things about him that I hadn’t seen or heard before. It was also very interesting to visit his home village and the house where he was born in Nárai in Vas county…

As far as Regösök is concerned, you are a Hungarian scout and folk dancer. How natural was that for you, especially considering that your mother is of Romanian origin and she also actively cultivates her language and culture?

My parents brought me up to respect both languages and cultures, and to try to balance the two in my daily life as much as possible. This was often a compromise, because there are only 24 hours in a day… I was active in Hungarian scouting from the age of four, and I joined the Regös group at 13 or 14, but I already started folk dancing at the age of 10 in the Romanian community. My mother is a very active member of the Romanian community; she was also the Sunday school leader at one of the Romanian Orthodox churches for a long time, and she has been involved in folk dancing for about 12–13 years; now she leads a dance group with mostly younger children as members. On Sundays, we used to go first to a Catholic mass at St. Emeric’s Hungarian Church, then attend an Orthodox liturgy at the Romanian church.

Let’s also talk about languages and weekend schools. Your parents speak to each other in English, but they use their mother tongue with you.

I went to the Hungarian weekend school for eight or nine years, where my grandfather used to teach for a long time. Going to Romanian school is a bit more complicated, because only the Romanian Baptist Church had a classic weekend Romanian school. I don’t know if it still exists today, but I went there for a few years initially, and later only to the Romanian Sunday school run by my mother in the Orthodox church. It wasn’t the usual 2–4 hours of weekend schooling, but I still learned a lot more than an average student from her, especially when I started to take an interest also in my Romanian identity. During the Covid pandemic, for example, I searched for small Transylvanian villages on Google Maps and read about ethnography…

I’m lucky because my parents taught me both languages properly and didn’t allow me to use English at home. They are a bit more relaxed about it by now, but it still often happens that if I try to say something to them in English, they pretend that they don’t understand, so I have to repeat it in their language. This was always the case when I was a child. Because I only spoke Hungarian and Romanian at home, I didn’t speak English until I was 3–4 years old, and in the first two weeks of preschool I came home complaining I couldn’t understand the other kids…

What role did your mother’s family play in your life?

My maternal grandmother lived in Nagyszeben (Sibiu, Romania, in Transylvania) before I was born, but following that came to live with us for longer periods and then moved here permanently around the time when I was 6 to be with me and both her children living in America. She shared the same house with us and spoke only Romanian, which helped me a lot to develop my Romanian language skills. My two grandmothers barely knew each other’s language, but tried very hard to communicate and even became friends. I miss them both very much….

They both helped me a lot to raise my interest in international relations and family heritage. When I thought that I should somehow bring my Romanian and Hungarian roots together, I could do it through Transylvanian ethnography, i.e. by trying to understand how these two nationalities lived and got along together. We often hear the narrative of how much tension there is between them, but there are also many examples of peaceful coexistence, of fruitful cooperation and common cultural heritage. My mother’s parents had lots of Hungarian and German friends. When she came to the U.S. in the early 1990s and married my father, her family jokingly told her: ‘You shouldn’t have to cross the ocean to have a Hungarian husband—you could have had one here’.

Cultivation of two languages, cultures and traditions from both sides is your family heritage. Is that the reason why, for example, your thesis is about the Csángós?

It was also a process to get there. In the first year at Princeton University, everyone has to take one compulsory course, where we learn how to write properly in academic style. In that course, my final project was on the Csángós. I’ve always been interested in them, because I found the balance between being Romanian and Hungarian in them. The Regös-tour was the next big step. We had been in Transylvania before, but in the Csángó region in Moldavia for the first time, where I became the interpreter for our group, because I was one of the only ones who could speak Romanian, and many times I alone understood about 25 per cent of what the old ladies said, who thoroughly mixed the two languages. It was also an extremely good experience, so I went back a year later. We were in Hungary and Romania with the family, then I went to the Csángó region alone for a few weeks. The Association of Moldavian Csángó Hungarians (MCSMSZ) runs various educational programs, and I went to help them with the summer programs. I got to know local people at a level I hadn’t experienced before. I gained several friends and had the opportunity to visit many different villages.

Did you also do research for your thesis?

Not at the time, but hopefully I’ll go back in January 2025. If I get financial support from the university, I’ll do more in-depth research. In any case, these trips have sparked a lot of interest in me, because it’s very different to read about a community than to experience it in person. For me, it’s a huge experience to see where these villages that I have read about before are, what kind of mountains are around them, or what kind of streets people walk on, what kind of houses they live in, how they raise livestock, etc. When I was there for three weeks, I didn’t stay in a regular house, but at a campsite in the middle of the village, so I got to experience the life they live up close—that helped me a lot to get to know the local community better, and to realize what I’m interested in the most.

And what interests you the most about the Csángós?

There are a lot of writings and research available about the assimilation of the Csángó Hungarians (with Romanians), but it’s still a big question how to preserve and perpetuate their culture and especially Hungarian language, which is losing ground very quickly. There are young people who still understand it, but few of them speak it among themselves. In a way, it’s similar to our situation in the North American Hungarian diaspora, because young people here also prefer to speak English to each other, but the language is more at risk there, because for example, for a very long time it wasn’t allowed to have Hungarian masses and education, and in many places it still isn’t. Nevertheless, I’m very interested in the question of how a community can preserve and perpetuate its culture. I have also researched this in the Cleveland context in another essay at the university. Now I’d be looking at how cultural associations and similar civil organizations influence the way historical memory and sense of identity are naturally formed. My hypothesis is that being strongly influenced by globalization, modernization and assimilation, the kind of historical memory or popular culture that existed 60 years ago will quickly disappear, but civil organizations that deal with cultural issues may influence this process. So my question would be how the organic minority community and civil organizations meet each other at the cultural level, how they strengthen or weaken each other.

There is a great tradition of civil organizations in America, but not in Romania, and especially not in the Csángó Region. Will there ever be an organization that you can research?

This is a project examining life after the regime change, i.e. after 1989. In addition to the association mentioned, there are a few smaller organizations as well. The MCsMSz operates Hungarian Houses. The churches themselves are also civil organizations, so I’d like to talk to some priests, too. There are a lot of things in my research plan that I need to try to simplify and may evolve in the meantime, but that’s pretty much my idea for now.

Let’s move on to your volunteer work.

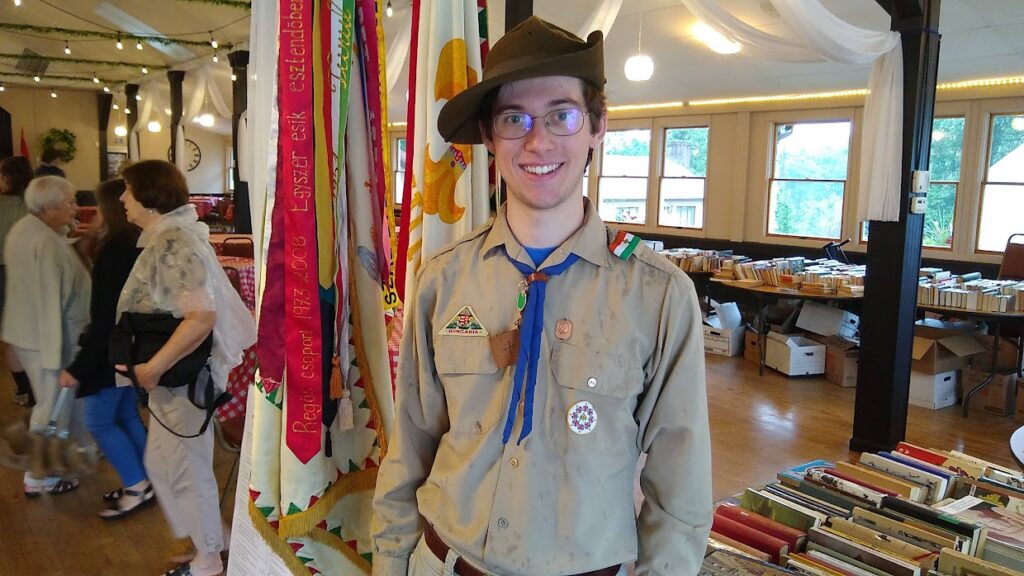

I’m a scout leader working with younger scouts. After the last Regös-tour, I went to Germany and took part in a leadership training camp, and became an assistant officer, which I wanted to do for a long time, but because of Covid and other things, I didn’t. I could have gone to Fillmore, NY, for the same leadership training, but I thought it’d be nice to experience a camp there while I was in Europe, and it turned out to be a very good decision. I’d also like to become a scout officer at some point in the future. Unfortunately, I can’t make it to scout sessions regularly from Princeton, NJ, but when I can, I visit and help out at New Brunswick, NJ, scout troop. I also had to take a break from folk dancing during university, but when home in Cleveland, I went to the Regös rehearsals leading up to the 50th anniversary performance. The old rule was that the upper age limit was 18, so university students were not supposed to join, but now there are more and more who participate later in life, and I think that’s a good development. Looking forward, I’d like to continue participating in Regös as much as possible. Besides this, I always help my father at the Hungarian Congress, mainly with providing the technical background, but I’ve also delivered lectures a few times. Additionally, I presented last year at the American Hungarian Educators Association (AHEA) conference in New Jersey. I also help my mother in the Romanian community: for example, I’m sometimes her assistant teacher in the folk dance group. In this context, I would like to share a thought I had with my father a few days ago.

As I see it, the problem is always the same across the various minority communities here: there are fewer and fewer participants within them. Those who’ve been actively involved in the communities’ life for a long time will of course notice this and understandably feel sad about it, but my view is that even if there are only three or four people involved in specific activities, we should continue the organizing work, so that our communities and their associations continue to exist. The worst that can happen to us is to give up: to close the association and stop the voluntary work, because then, even if later someone tries to reopen and continue it, people won’t come back. This is the current situation of the Romanian community. The oldest Romanian American organization is still around, but very small and not active—I think the worst would be for them to close it down and move on, because then we’ll lose the community strength and the shared history that these organizations have. This is very important to me…

Is it so important that you’d even help them keep it? Tell us more about the local Romanian community.

Yes, I’d love to help to keep the organization going. The Romanian community in Cleveland is not as big as it used to be or as it still is in other places like California or Chicago, even though Cleveland used to be the same for Romanians as it is for Hungarians: a spiritual capital, so to speak. For example, there was an umbrella organization for Romanian groups called the Union and League, and the oldest Romanian Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches in America were built here. The Romanian community is roughly the same size as the Hungarian community, but in many ways different. The Hungarian community has had waves of immigrants, starting with the so-called ‘Old Americans’, followed by the refugees of World War II and 1956, followed by waves fleeing communism and then those who came after 1989. The Romanian community has the same, but I think most of the people who speak Romanian today and are active in the local Romanian community came after the fall of communism. Interestingly enough, a lot of them came from the same region of South Transylvania, like my mother. And this was similarly the case in the early 1900s. Chain migration is the phenomenon where relatives and friends immigrate one after the other. For example, my grandmother’s home village of Arpașu de Jos in southern Transylvania used to be referred to as ‘Little America’, because more people left the village to America than stayed. My mother came here to visit friends in the early 1990s, and also ended up staying here. The two communities are also different in that, apart from the current two folk dance groups, the Romanians are all mostly based around four large churches: two Orthodox, one Greek Catholic and one Baptist. This is another problem—not the churches and their communities of a combined 500–1000 people, but the fact that there is practically nothing else—we are trying to fix.

Your parents were not only taught to respect both cultures, they live by them. Your mother was present at the Hungarian Congress, helped at the Scout Day.

Yes, my parents have always helped each other’s local communities. For example, my mother used to organize one of the lunches at the Hungarian Congress for a long time. My father managed the website of one of the Orthodox churches for many years. When the local Romanian newspaper still existed, my parents edited it together. My father often filmed at Romanian events, and when my mother organized something with the dance group, my father helped her. They are important members of both communities and have friends in both. My father is loved by many in the Romanian community, and many from Transylvania try to talk to him in Hungarian.

What are your plans for the future?

I’d like to continue my studies; the question is whether it’s straight after university or if I would do something else first—I’m trying to figure that out now. I don’t know yet if I want to do a PhD, but I’m not ruling it out, because I’m interested in an academic career, too. The other idea I have is to pursue the international relations track, because I’m interested in diplomacy. I already have my Romanian citizenship and I’m working on obtaining a Hungarian one, so the whole EU world is open for me. A few years ago I did a traineeship for the Romanian government in Vienna, where I had a very nice Transylvanian Romanian supervisor, so I’d enjoy similar work. The other possibility is to do something at the EU level, where they have scholarship programs too. The third option could be that I might go to Europe through the UN. I’ve just started looking around at the different opportunities and applications. I’ve already applied for a Fulbright grant with the plan to return to Romania and do further research among the Csángós. Whichever path I take, one thing I would surely like to do: to connect my life in the diaspora in the U.S. with Central and Eastern Europe. Since there are Hungarian and Romanian civil organizations dealing with these matters, of course I’m interested in them too. My personal life depends on my professional life, of course, but I surely don’t want to lose my connection with Cleveland; wherever I live and work, I always want to be actively involved in the communities there. That’s my small Hungarian and Romanian village; I belong here and consider myself a Hungarian and Romanian living in the diaspora. No matter where I’ll live and what kind of job or career I’ll pursue, I’ll try to remain involved in the Hungarian and Romanian communities of Cleveland, because that’s my duty.

Read more Diaspora interviews: