Dr. Judit Tamás came to America thirty years ago as a kindergarten teacher through a scholarship program. She quickly became involved in the Hungarian community in Buffalo, New York, and a few years later moved to North Carolina for her husband’s job. When their three children were born, she founded the Carolinas Hungarian Group, organized camps for Hungarians for twenty years, and later launched the popular Online Hungarian School (OMI), which she has run for fifteen years. Nowadays they have 250–300 students from 50 countries studying in 50 groups.

***

How did you end up in North America?

I graduated as a kindergarten teacher in Hungary, and worked as an educator in the UK for two years. In 1993 I was offered a scholarship to the U.S. thanks to Péter Forgách, who helped many talented young Hungarians to continue their studies in America and to contribute to the development of Hungary upon their return home. I was one of the first students. I first earned a master’s degree in early childhood education from the State University of New York at Buffalo, and then supplemented it with a doctorate. In the meantime, we established an exchange student-teacher program between the American university and a teacher training college in Hungary. In addition, we brought many international conferences to Hungary. There was a great deal of Hungarian–American networking in the first few years after the fall of communism.

The Hungarian community in Buffalo wasn’t very large, they didn’t have a Hungarian weekend school, for example, but they had Hungarian scouting, which I became involved with. Since scouting starts at the age of five, I started a kindergarten class for younger children so that by the time they get into scouting, their Hungarian language skills would meet the expected level.

You were also active in North Carolina from the beginning…

We moved to North Carolina at the end of my doctoral studies, because my husband got a job here. After those years in Buffalo, where we had a strong connection to the local Hungarian community, we really missed something similar in North Carolina, so, together with another Hungarian family, we started to ‘hunt for’ Hungarians one after the other, for example on iwiw, an early Hungarian social media site, which was popular at the time; or we would open up the local phone book and write to people with Hungarian names. We started with very small steps, and as the community grew, we organized bigger gatherings. Once we had a presence on the Internet, it was easier for people to find us. And later we started the camp—that’s how the Carolinas Hungarian Group was formed in 2000.

Your camps are popular across America. How did you start organizing them?

We live far away from each other, so we couldn’t get together regularly. In the camps we meet less often, but we’re together for days, which makes it worth driving several hours. We used to organize camps twice a year, but since the Covid pandemic, we only have the Easter camp. It’s a family gathering, where we also take care of the non-Hungarian speaking spouses by organizing activities also suitable for them: handicrafts, folk dancing, cooking, sports competitions. The Easter camp is based around the Easter holiday theme: we celebrate Hungarian Easter traditions, decorate eggs with various techniques, do sprinkling, dress up in folk costumes, invite a band, folk dancers and craftsmen. We once organized a complete traditional wedding ceremony—it’s the kind of program that even people in Hungary don’t necessarily experience. We invite guests from Hungary too. Camps of several hundred people running for several days like ours are rare in North America. We prepare for at least half a year, to make sure that everything will be in order: accommodation, meals and programs for all ages.

Where do the participants come from and what is the camp venue?

Participants come not only from the two Carolinas, but also from states further away. The spring camp coincides with spring break for many, so with one or two extra days off, they can come even from quite a distance. Since the dates are known for a year in advance, many people organize their vacations accordingly. Some people still come back after ten years. It’s very difficult to find a suitable location for such a huge and diverse event, where there is enough space for cooking, folk dancing, etc. The Easter camp is usually held in the mountains, while the autumn camps were held on the beach. We try to organize them in a way that is physically and financially accessible for everyone.

I used to organize them for twenty years, but since the school has grown to become large, organizing camps no longer fits into my life. Meanwhile, my children, who were born when we started all this, have grown up. We have managed to involve the new generation with young children, both as organizers and participants, so fortunately there is enough fresh supply ensuring the camp’s future.

Where did the idea of the OMI come from?

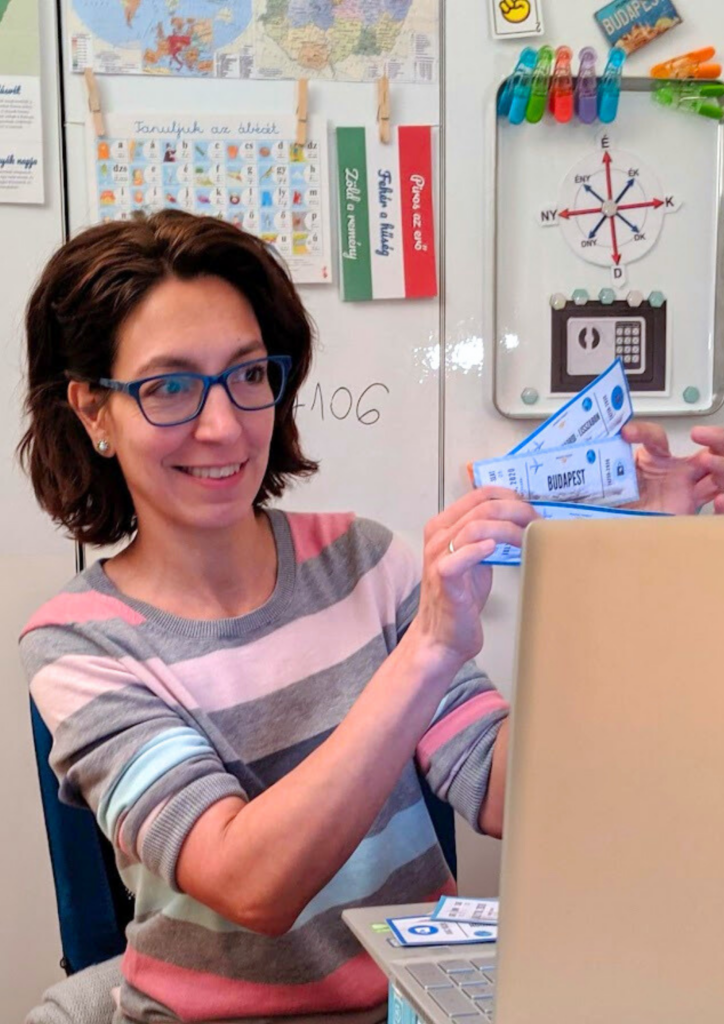

The camps were organized online; that’s where the idea came from: if we’ve been working together for years and we can discuss and organize practically everything online, why don’t we try to teach the children in the same way, since we couldn’t have a physical Hungarian weekend school locally because of the huge distances that set us apart? We teamed up with a few other mothers—teachers by vocation—to create an online classroom for the children of the Hungarian community in the Carolinas. We first called it a book club to motivate them to read. Then we created a small website, where we started to upload all kinds of educational materials, and then we started the lessons. Since the Covid pandemic, online lessons are in the public consciousness, but at that time it was a rarity. It worked absolutely well, and it grew into a school, which operated within the Carolinas Hungarian Group for a long time, until it outgrew that organization and we became independent in 2021.

OMI has reached 50 countries and 50 groups in 15 years. How?

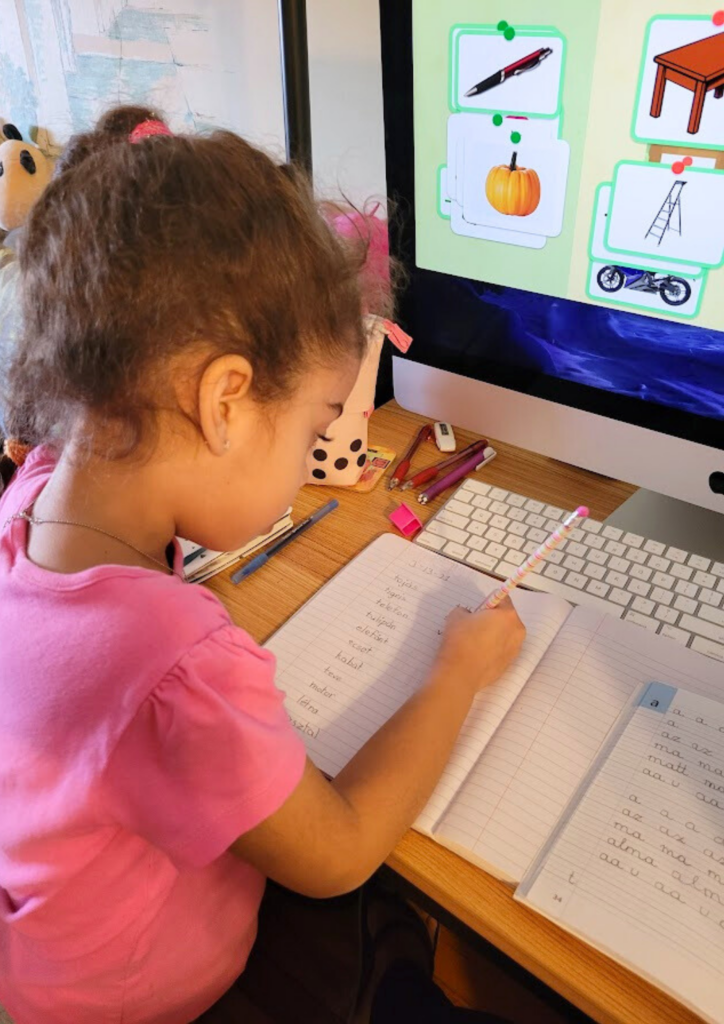

At first, we worked with one group, but very quickly we realized that we had to break them down into age groups. Families where we started with their school-age children asked if we had a program for the pre-school age group; later many parents were interested if their teenagers could also join; so we started teaching younger and older children. When non-Hungarian-speaking family members asked for language lessons, we started to work with adults, too. Some came to us with special requests; for example, Bible lessons, chess classes, online camps, music classes for the little ones. We now have a reading club for teenagers, who love to talk about books. But we also have mother-baby classes, toddler classes, puppetry, vocabulary and language development classes, reading and writing instruction including cursive if requested by parents, music lessons, and various subjects such as history, math, literature and grammar as well as Hungarian language classes.

In the meantime, we started to get requests from other states, and then from abroad. It turned out that there are Hungarians everywhere, including very faraway African and Asian countries, too. Sometimes they come from such exotic places that we have to check the map…We have about 250–300 students per year, only about half of whom now live in America, and in total we have had several thousand students in 15 years, which would be difficult to count because many attend more than one class. We have roughly 700 classes per semester, with classes every day, from Monday through Sunday, from morning to evening, mainly because of the different time zones. I don’t think any other school or organization could meet the need to provide Hungarian learning available anywhere in the world.

How big are these groups?

It varies depending on the age and profile of the group. For example, the smaller the children, the less they can wait for each other; everyone wants to tell their story or show their work at the same time. So the younger groups are smaller, but teenagers work well in larger groups. If there are requests from very specific time zones or requests that we know in advance won’t attract more applicants, we’ll start the group even if it’s financially unprofitable, because we don’t want to send anyone off. We’ve decided many times not to have more groups, not to expand the timetable…and then a request came in that we accepted it. We try to find a way to reach everyone, and we also give private lessons within the school. We take on the preparation for the Hungarian exam for children who want to move to or return to Hungary. On the other side, there are second- and third-generation parents and children who have never or rarely been to Hungary, because not everyone can afford traveling overseas—they also have to be taught in a very different way.

What should parents do if they are interested in OMI?

There’s a detailed timetable on the website, but it’s not easy to navigate; sometimes even we have to check twice before we recommend a class. Parents need to fill out a small application form on the website, enter the age of their children and what they would like to do. We then offer them ‘trial lessons’, where we introduce ourselves and get to know the families. One of the great advantages of online school is that there are so many options and we can cater for all needs—that’s why it’s so important to have this trial lesson, which we can do quickly, but we don’t hurry if the child enjoys it and the parent is available. Parents are usually very keen to talk; they want to tell us not only what they want and why, but also their whole situation: whether there is a Hungarian community around them, what bothers them regarding their children’s education, etc. In this process, we try to assess and then take all aspects into account—age, Hungarian language skills, personality, group dynamics—to create as homogeneous a group as possible. Every good teacher differentiates, but it’s easier to make progress if you don’t put, for example, a linguistically beginner 10-year-old in the younger group, because a 10-year-old needs very different methods from those used with 7–8-year-olds, not to mention teenagers. We then offer them possible groups they can try out, because it’s very important for us that they feel that the teacher, the level and the group itself is suitable for their children. If it turns out after the first class that the level isn’t right, it’s possible to change groups and try another one. And we never ask for tuition fees in advance because we trust the families—that’s also rare.

What do you usually experience during the trial lessons?

Families are very busy. It’s hard to find free time even for the kindergarteners, because they have so many extracurricular activities and spend so much time traveling. We’ve helped many families who have slipped into everyday English use; because they are afraid of falling behind at school or because for various other reasons, they prefer not using Hungarian, and thus even though the child understands Hungarian, they prefer to respond in English or in the language of their countries of residence. One of our aims of the trial lessons is to encourage them. Often parents come to us saying that their teenager doesn’t want to join, can we persuade him? In such cases, it’s also our job to get them interested and to support their parents so that they don’t give up on it. Our school is not just about the lessons and classes, but much more. It’s a community where parents are similarly situated—that’s why we set up a parents’ group and various communication channels to talk to each other. Sometimes we also invite experts, but often we don’t need one, because there is so much knowledge accumulated in the families that they can learn a lot from each other. And then there is our currently 22 strong teaching staff including teachers with all kinds of qualifications, who have not only graduated in Hungary but also have a lot of experience in teaching Hungarian children living abroad—because they need both: not only their basic subject-matter expertise, but how education works for children living abroad.

Is there anything else that OMI can offer?

We have many children who also attend local Hungarian weekend schools, but that’s usually not enough: many parents want more, something different. It’s also very helpful for private students, because there is a community here. And they can’t learn subjects like we do in other Hungarian weekend schools: high level math, physics, geography, history, folklore, folk dance…All subjects can also help a lot in the local American, German, French, etc. schools, because they learn about things that make them more informed. It’s not just about teaching Hungarian, it’s teaching all kinds of subjects in Hungarian. Since the children otherwise live in various cultures and languages, we often discuss traditions and holidays celebrated in their countries of residence, so they learn not only about Hungarian culture, but also about their other countries.

We also prepare them for various Hungarian and international maths competitions; where they’ve achieved very good results. Many of our children know more about Hungarian ethnography and folklore than a child growing up in Hungary. We put a lot of emphasis on Hungarian identity, so that they are proud of their origins, traditions and of Hungary in general. It’s important that children who speak Hungarian well also go to Hungarian schools, and for as long as possible. Our aim is to start as early and keep them in the system as long as possible. That’s why we have scholarships; school shouldn’t be a financial issue. Teenage years are very important and decisive: we can have a big impact on the children, and since they will go to university or college afterwards, we have to make them love Hungarian language and culture before that, so that later on as young adults they themselves will look for opportunities to get into the Hungarian communities, go to folk dance events, pick up a Hungarian book, etc. We have a lot to do until then…

You mentioned you have highly qualified teachers.

When we occasionally put out a job advert, they find us from Hungary and Europe. There are fewer qualified teachers with college degrees who can teach at OMI. We have some teachers who teach very intensively, up to six or seven groups, and some who have fewer groups, but all of our teachers have a passion for teaching. Those who love teaching will sooner or later find the opportunity to continue their profession, even when they live abroad.

Our teaching staff includes various subject teachers, drama teachers, speech therapists, Hungarian as a foreign language teachers, ECL language exam instructors, etc. This is also the strength of our school. We have everything under one umbrella for parents, and our teachers work together. We have an online teachers’ room where we communicate constantly, discuss successes, challenges, best practices, and learn from each other. Online teaching can be a very lonely activity if you’re doing it on your own. It’s very important to help and mentor each other. The field of online teaching and digital pedagogy is also constantly changing and evolving. Even after all these years we can’t say we know everything or that we would have the industry knowledge at our fingertips. That’s another reason why online school is good and people like teaching here: they have to be creative. We organize a lot of training for ourselves, we have monthly meetings, we train each other about the use of various educational applications and we have sub-teacher groups, collaborating constantly.

Are there no disadvantages of online teaching? Some are afraid of it, for example because of the assumed excess use of computers or the lack of personal touch…

All I can say is: if you are afraid of it, come and try it with your child. There are professionally proven ways to do it well. The classes last one hour each, so the child is not sitting in front of a computer all day. Technology cannot be excluded from children’s lives. At the same time, nowadays there are many technology rich schools, classrooms where several types of technology are used regularly to enhance teaching and learning, such as interactive whiteboards, mobile devices. Hungarian schools also have to change; we can’t just photocopy worksheets. Online education must also be entertaining, interactive and experiential. During the Covid pandemic, the world was suddenly forced into it, schools had to switch quickly to online education, but OMI is different. For example, it certainly brings out the best from teachers. I’m not saying it’s easy, we all get physically tired in 60-minute lessons that require a lot of preparation too, but it has its advantages: children get a very high-quality education and a supportive community that you can never have enough of. Moreover, there are certain subjects and activities that work well online. Families are also involved. In the case of weekend schools, parents don’t necessarily know what their children are learning, but here they get lots of ideas that they can try out for themselves. New traditions are adopted; new topics are introduced into families. All our materials are accessible for those enrolled. We give homework but nothing is compulsory. However, if someone wants to practice at home, we want to help. Activities are not only virtual; we do a lot of hands-on learning, e.g. making a model of the Chain Bridge or collecting something from nature. We make puppets and a variety of crafts and we have many extra-curricular and community-building activities, such as online story time, puppet shows; even online folk dance parties, completely free and open not only to enrolled students but to anyone.

This year, you received an award at the annual American Hungarian Schools’ Association (AMIT) conference.

We regularly attend AMIT conferences; six of our teachers were there this year. During the Covid pandemic, we helped a lot of schools and organizations. Some Hungarian weekend schools didn’t switch to online education and sent families to us; at some others we ‘just’ helped out. We are happy to show them our methods, provide materials, and they can watch our lessons anytime. Our teachers are often invited to conferences, and if someone is considering switching to online teaching, they often contact us.

Certainly, I’m not the only one who received this award but our whole staff, although there were times when I have run the school completely on my own. Currently there are three board members running the school, and we all have our strengths. My field is pedagogy. Being a school principal is already out of my comfort zone, and it’s not always easy to lead a teaching staff of 22. The time zones are also a challenge: when some teachers go to bed, others get up, and there is no end to it. We work from home, most of our classes are on weekends, for example we have 12 classes on Sunday. From my own time zone perspective, the first Asian group starts at four in the morning, and the last starts at eight in the evening, so my computer is basically always ringing. It’s not easy to manage, but we complement each other well, because the financial, technical and administrative part of running a school is handled very well by Tímea Szonja Ollári-Homor. Zsuzsa Lantos, a geography teacher, is our deputy principal, also teaching at the Arany János Hungarian School in New York. Our teachers are usually community leaders, physical school directors, event organizers.

If everything goes so smoothly, I guess you’ll be running it for a long time.

Well, there have been ups and downs…There were times when I wanted to give it up, but there were always some teachers and parents who said, ‘Don’t give it up, we’ll help you, we’ll figure something out together.’ They were always very supportive and thus we always kept going. There were times when I even wrote down that I was going to quit, so that I wouldn’t forget the next day and get over the annoyance, but then a letter would come from a child or a parent saying they can’t wait for the next semester to start…As long as we get feedback like this and we have plenty of applicants without any advertising, we’ll continue. For now, it’s me who takes it forward, but I’m sure there will be others who will continue OMI, because by now the whole system is well-functioning, teachers and parents got used to it.

Read more Diaspora interviews: