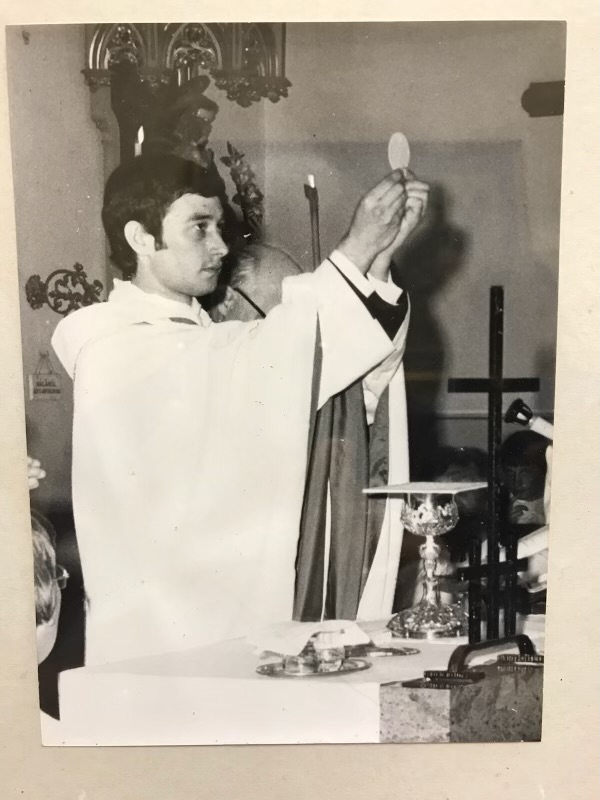

Barnabás G. Kiss was born in 1953 in Kapuvár, Hungary. After being ordained a priest in 1978, he served as a chaplain for five years. However, to realize his plans for a religious life, he had to leave the country. He has been serving for 40 years in the U.S. with his fellow friar, Father Angelus Ligeti, by now as the only two remaining Hungarian Franciscans in the U.S. After ten struggling but fruitful years in Ohio, they undertook the task of saving the Holy Cross Hungarian Parish in Detroit, which will be 120 years old next year. While trying to keep various church communities alive in the Great Lakes region, he also strives to keep the Hungarian priests in the North American diaspora together and advocate their cause to their bishops in North America as well as the bishop in Hungary in charge of the Catholic Hungarians living abroad.

***

What led you to become a priest and a Franciscan monk?

My parents were deeply religious working-class people. Even though I grew up in Kapuvár in the 1950s–1960s during the communist regime, which was fiercely anti-religion, I went to mass every Sunday with my parents, where I served and read as an altar boy. Because of these and considering that I wanted to be a student at the Czuczor Gergely Benedictine High School in Győr, I couldn’t ever be graded as an excellent student in the local elementary school. I owe eternal gratitude to my Benedictine monk teachers, who educated and trained me and made a man out of me during those four high school years. I was thinking of a monastic vocation, but at that time the three orders not banned by the communist government could only offer training as a priest-teacher. I did not feel qualified, so I applied to the diocesan seminary in Győr. The price I had to pay for this was two years in the army. There were 52 seminarian priests in the barracks in Nagyatád that year. The system didn’t realize that we were actually much better off together. I left my Scripture as a memento to the Squadron Commander, because he became interested in religion while I was working for him as his assistant.

What happened afterwards? Did the communists indeed try to ‘recruit’ you?

In 1973 I could start at the Theological College and Seminary in Győr. It was a fateful moment when I met Father Hilár László Dömötör, who introduced me to the Order of Brothers Hospitallers, which was functioning underground at the time. I was struck by the love, respect and help given to the elderly and the sick, and the fact that we not only talked about it, but also acted on it. Unfortunately, we quickly ran into the spy network of the communist regime, so it was safer to be ordained as a priest for the Diocese of Győr. My ‘recruitment’ was repeatedly attempted by the communist authorities, both during the years of military service and those of the seminar. By nature, I’m easy to get in touch with people; since I’m honest, people like to talk to me honestly. I’ve been regularly approached to help reveal which teachers or other people in high positions have had their children baptized, or secretly received sacraments. They reached out to me, floating ‘great ideas’ about how to advance my career, which I always thanked, but didn’t ask for their ‘help’.

Was this the reason for you leaving the country after five years of service?

After being ordained as priest in 1978, I served three years in Szany and then two years in Csorna. I have very good memories of those years. I was often able to strengthen people’s spirits, prepare them for death, or even keep the whole family religious, so that they decided not to have a funeral organized by the Communist Party, but with a Catholic rite. Some people contacted me privately and confessed that they didn’t dare to take communion in front of others but asked me to let them take it privately. I felt I could help people a lot. However, other types of messages also reached me, and I didn’t plan to end up as a martyr just because I refused to serve the communist regime. In 1983 I decided not to return after a 30-day-long vacation in Austria. I remained within the Order of Brothers Hospitallers, so that I could fulfil my old dream. Fr. Angelus Ligeti and I began our noviciate year in Austria with the intention of returning home as soon as the regime changed in Hungary. But the Lord had other plans… Soon after the visit of the bishop of Catholic Hungarians living abroad in Mariazell in 1984, we found ourselves in the U.S. On 30 November, it will be 40 years that we’ll have been living in this country.

What memories do you have about the first ten years you spent in Ohio?

In Youngstown, Ohio, we became involved in the work of the Hungarian Franciscan friars of Transylvania (Romania) in the Headquarter of St. Stephen Franciscan Custody founded and operated in the U.S. In addition to pastoral ministry and spiritual exercises, I received great help to strengthen my Hungarian identity in the person of the famous Hungarian writer Albert Wass. From 1985 to 1993, I was the publisher of his books and co-editor of the weekly newspaper Catholic Hungarians’ Sunday, launched in 1894. It was a fateful moment when we had to stop publishing the centenary paper. The Hungarian Catholic Bishops’ Conference and the Minister General of the Franciscan Order thought that the anti-communist tone and style of the newspaper was no longer relevant after the change of regime in Hungary in 1989–90, and it should be handed over to secular publishers. In December of the same year, it was revealed that the Custody of St. Stephen and St. John Capistran would be discontinued in the U.S., because the friars had grown old and most of them had moved back to Transylvania or Hungary.

Why did you stay?

Initially, to keep the newspaper alive for at least a hundred years. Later, because we knew that those Hungarian parishes in North America from which the Franciscans had left and hadn’t been replaced by Hungarian priests would all be closed. We decided to continue the Franciscan mission by taking on a Hungarian parish. That is how Father Angelus and I arrived in Detroit on 3 February in 1994. Franciscans never live and work alone; they are always working in fraternity, for the work the community needs from them. By now, we extended the life of this parish by 30 years. This community, which will be 120 years old next year—with its 100-year-old church building—, has helped us and we’ve helped them to make the best out of the existing situation; both from a liturgical and a Hungarian community building perspective. We say four English-language Masses during the week, because most people attending those understand only English. On weekends we have three Masses: English on Saturday at 4 pm and on Sunday at 9 am, and a Hungarian service on Sunday at 11 am. I spoke in two languages at today’s mass because some 30 per cent of those of Hungarian descent in the congregation no longer speak or understand the language, and many have mixed marriages. As you must have noted, I don’t repeat in English what I’ve already said in Hungarian; I alternate languages in the process in such a way that those who understand one language can understand the message, which today was: don’t abandon this church and parish!

40 years of joint service is very long… How did you get along?

My mother considered Father Angelus as ‘her son’ and my ‘found brother’, since my brother died when he was a child, and my sister lived abroad. Angelus is a fellow friar, a fellow priest, a friend and a brother. We proclaim the same Christ as the two disciples on the road to Emmaus. I’m the parish priest, he is the head of the friary/rectory. There is a stable rhythm to our days with Holy Mass, prayers, meals and free time together. Without him, I couldn’t go anywhere, either to Hungary or on any missionary or pastoral work. Because there are two of us, the representation of the Franciscan spirit can appear in several places all at once, especially in these years when we are celebrating 800 years of several Franciscan anniversaries. We are very strengthened by these 800 years of Franciscan spirit, there is no rivalry or jealousy between us. I’m happy if Fr. Angelus does something better than me. I enjoy attending the liturgy he leads and I’m also very happy for his musical talent.

What is Fr. Angelus better at?

His sermons are much shorter; he often speaks in a sort of bullet point fashion. He is very modest, quiet, and reserved. His words have great value. He strongly believes that you don’t say more than you know and don’t commit to something you can’t keep. He’s a very good adviser and teaches a lot of patience. He is humble, not afraid of any job. If needed, he mops, vacuums, does anything that’s important to the Church. He warns me to be sober in relation to the community. I tend to have strong opinions, sometimes divisive, and that’s not always good. I always express that I was born Hungarian and Christian. I never give up this principle: we can’t slice ourselves up. Christianity and Hungarian identity must go hand in hand as one weekly Mass isn’t enough to connect. We need to organize several social events to have an active community and to keep our Hungarian traditions alive—not only with God’s word, but also with cultural experiences.

How big is the community you serve?

We don’t keep very accurate records, just a list including the regular churchgoers, but there are those who come only for the major Holy days, those who live here temporarily, and those who are ‘only’ supporters—thus, whatever number I give you, won’t necessarily be realistic or indicative. We currently have around 350 families or individuals on our list; we send out around 400–500 invitations before Easter and Christmas. There were about 150 people at today’s Feast Day of our Church—The Exaltation of the Holy Cross—that should be at an average service. About 30 people attend on Saturday for the Vigil Mass and about 50–70 on Sunday morning for the English Mass. I can combine Masses only during Easter and Christmas or larger events, to have a bigger attendance and celebrate together. I greet everyone I know around their birthdays, name days or wedding anniversaries.

‘Christianity and Hungarian identity must go hand in hand’

Like other Hungarian churches in the diaspora, we have a large area of more than fifty miles to cover. When our churchgoers get so old that they can no longer drive, we have to go after them to visit or ultimately bury them. This weekend, for example, we had a funeral 55-minute drive away from here and then a wedding at the church. Because of these, I couldn’t join the Pig Roast event at the Hungarian American Cultural Center, where I usually not only say prayers, but also address people, invite them, and announce church events to them. Many people claim the church is too far away. In fact, it’s in a very good location, close to major highways. It’s rather the case that people going to a Hungarian event on Saturday find it difficult to visit the Church on Sunday—even if the Mass starts at 11 am.

Besides, we used to serve the cities of Toledo and Akron in Ohio for a long time. In DeWitt, Michigan, there is a former Franciscan retreat house and in Flint, Michigan there is still a Hungarian community, but no Hungarian-speaking priest anymore. We’ve also been going over to Windsor, Canada to serve the Hungarian community of St. Anthony for ten years. We used to go weekly, but now we only have a Hungarian Mass once a month. I went to St. Stephen’s Church to New York for 26 years and provided pastoral services there in every Lent and Advent.

What changes have taken place at your parish over these past 30 years?

Only a part of those who have grown up here have stayed with us, and many have mixed language families. After first communion and confirmation, the momentum of church attendance slows down considerably and would only return with marriage and children, if at all. Our numbers keep fluctuating, while the community as a whole is dwindling as everyone ages. However, there has been some positive changes. The eight-grade parochial Hungarian school was discontinued in the 1970s as the population of the area changed. At the same time, the Archdiocese of Detroit made it compulsory for parents of children attending Catholic school to attend the church where the child goes to school. They were also incentivized by a 50 per cent discount on the tuition fee. Our parish lost a lot of families because of this requirement. I started the fight to change this unjust regulation in 1997. The archdiocese finally accepted my argument. As a result, some of the families that our parish previously lost have returned, but now prefer to come to the English-language services, because in those times Hungarian immigrant families often encouraged children to learn English as soon as possible, as the parents were struggling with it. As for our 30 years here, let’s start from the fact that this parish was doomed in 1992–93. The archdiocese planned to turn it into a Spanish-speaking parish sooner or later. We added thirty years to this Hungarian parish’s life, during which I believe we’ve reached everyone who wanted to belong here. This role of the church lives on to this day. Its fate touches everyone sensitively, we often hear: ‘as long as I can, I’ll come’, ‘as long as I can, I will pray and sing in Hungarian’, ‘as long as I can, I want to hear the word of God in Hungarian’. The strength of this desire certainly varies though in our community.

Currently, the situation is critical, you said. Could you elaborate?

Young people nowadays should be taught to appreciate our Hungarian language and our Christian culture… Religious education takes place between the two Sunday Masses, in two languages. When I prepare children for first communion, confirmation or confession, I always urge them to learn the prayers in both languages. Obviously, in an ideal world, they could only hear the teaching, the Mass and the hymns in Hungarian, but that’s no longer a reality. There has been no Hungarian language teaching here since the Hungarian parochial school was closed in the 1970s. When we tried to start scouting, we failed. The nearest scout troop is in Cleveland, Ohio, a two-hour drive from here. This is one reason why the number of kids attending religious education is very varying. Although the community seems to want Hungarian-language service, and most of them are willing to make a sacrifice for it, they don’t sacrifice as much as is necessary for the long-term survival of the parish… Today’s middle-aged people should take over the baton from the elderly. Today’s parents, however, with some exception, are falling into the error of American culture: they want their children to be professional sport champions or artists. The competitions take place on Sundays, like in communism. You can’t reach a family even if you meet them once a week for Mass, where you have to pay attention to everyone and leave something lasting in everyone’s hearts. Detroit isn’t like a village or a neighborhood where you walk over to church. Taking one’s faith and Hungarian identity seriously here, it’s not easy. We haven’t left yet, but will there be anyone to find us in a few years? Our presence is safe for the moment—in terms of building, funding and churchgoers—, but we only have a future together. Everybody should make the maximum sacrifice.

How do you see the future?

This is a complex, multifaceted issue. Now, we are the only two Hungarian Franciscans in the U.S. We are members of the Franciscan Province of St. Stephen, King of Hungary in Transylvania (Romania). Our headquarters are in Kolozsvár (Cluj, Romania) and our Minister Provincial is Fr. Erik Urbán, OFM. The Holy Cross Hungarian Parish in Detroit is a mission house of the province. The essence of the Franciscan charism is to support a mission with physical presence or some kind of a Franciscan ministry. But this isn’t a Franciscan parish, we don’t own it, we only serve here. The Archdiocese of Detroit has the right every six years—which term, by the way, has just been restarted—to re-assess the contract with the parish and at one point they may not renew it, because they no longer see it as crucial to have a Hungarian parish here. That’s also happening in Canada where the Hungarian parishes are being eliminated one by one by the local bishops. Until now, our community was an ethnic parish, but we’ve recently become a family of parishes with several parishes—what this means for the future remains to be seen… We are often asked: why, decades after the great waves of immigration, do we still need Hungarian Masses when everyone speaks English? And we often ask ourselves: if the work of the Holy Spirit does not have such a power to make Hungarians realize what their role is, if they are indifferent to or fed up with their fate, do we still have a role to play? In short, as long as our Franciscan Province maintains this mission abroad and designates us to stay here, and as long as the Archdiocese of Detroit renews the contract with our Province, we’ll stay—our health permitting. In the meantime, we need to find the successor Hungarian priest.

‘Our presence is safe for the moment, but we only have a future together’

I’ve received offers from many places, but always replied: I am not ready to leave the U.S. As the North American delegate of the Hungarian Catholic Pastoral Service Abroad, I have always tried helping the Hungarian pastoral service in the North America diaspora. Wherever I could, I made sure that there would be a succession, either another Hungarian priest, or at least a stable mission in the hands of civilians. I would not like to leave a gap here after me or us, either…

What have been your specific tasks as a delegate?

The Bishop of Hungarians Abroad was previously Attila Miklósházy in Toronto, Canada and before him László Irányi in Washington, DC. Their immediate superior was the Pope. After the fall of communism, Bishop Ferenc Cserháti was appointed to this position, and became in charge of pastoral care for Catholic Hungarians living abroad as the Auxiliary Bishop of Esztergom–Budapest. The Hungarian Pastoral Service Abroad operates within the framework of the Hungarian Catholic Bishops’ Conference and has had its headquarters in Budapest since then. Since we live in various dioceses in North America, the jurisdiction and the opportunity to serve is granted by the local American or Canadian bishops. As a delegate, in addition to organizing Bishop Cserháti’s trips to North America, I have tried to coordinate the Hungarian parishes’ contacts with the bishops in North America and in Hungary, as a liaison in the relationship between these two separate worlds. For example, in the last Hungarian parish on the East Coast (St. Stephen, Passaic, New Jersey), we have recently needed to find a successor of László Balogh, Pastor, therefore Father Imre Juhász from New Brunswick became the pastor also in Passaic, while serving in his previous St. Ladislaus Church, and the Hungarian community in New York. In Windsor, Canada, on the other hand, the Hungarian Catholic community has lost its second Church. The Hungarian parishioners need to attend the Hungarian Mass in a Canadian church, where much depends on their relationship with the pastor.

You are also president of the Hungarian Clergy Unity in the US and Canada.

It is about Hungarian priests in North America working together: since we cannot work together physically, at least we should align remotely. Every year we have an ‘Emmaus meeting’ after Easter to strengthen ourselves: there Jesus is with us, and we are with each other. For the last 17 years I have been organizing these meetings in Ancaster, in a house of spiritual retreat near Hamilton, Ontario. We have had such a retreat every year except for the Covid pandemic and last year, due to the illness and death of Bishop Ferenc Cserháti. Since then, the Auxiliary Bishop of Esztergom–Budapest, Gábor Mohos—Pastor of St. Stephen’s Basilica in Budapest—has taken over the office in the Hungarian Pastoral Service Abroad from Bishop Cserháti. He works together with Auxiliary Bishop Kornél Fábry, who will be on a pastoral visit to North America between 24 October and 5 November this year.

Read more Diaspora interviews: