I’ve heard a lot about Györgyi Gyulassy in connection with the Kodály Weekends organized for Hungarian Scouts on the East Coast of the U.S. Still, it wasn’t until last fall that we met in person at the Meeting of American Hungarian Schools (AMIT) in New York, where she taught flute to teachers with a cheerful smile. It was then that I learned that she’d lived in California for many years, started teaching singing and music to Hungarian scouts there, and then moved to New York for her husband’s job and founded the Kodály Weekends that have been organized since despite her moving back to California nine years ago.

***

How and when did you come to America?

I was born in Felvidék (today’s Slovakia) in an almost purely ethnic Hungarian village, Gúta, where, after a while, Slovaks were constantly moved in by the Communist authorities to forcefully distort the ethnicity of the village. My dentist father wanted to make sure we grew up as Hungarians, so he arranged for us to move to Hungary in 1959 based on my mother’s Hungarian citizenship. We lived in Budapest until the house searches by the Hungarian Communist authorities became unbearable…

What happened?

The Communist secret service wanted badly to somehow incriminate my father, for example, by regularly searching our house for ‘spare gold’. He decided to immigrate with his family to the West as soon as possible. We finally succeeded in 1963, first to Italy and after six months to America. An uncle of mine, the famous Father Kristóf Hites—for us, just Uncle Bandi—lived in California and, together with 12 fellow Hungarian refugee monks, founded the Benedictine Woodside Priory High School in a beautiful environment. The school had a fantastic reputation; affluent people from all over the world sent their children there to be groomed by the rigorous Hungarian monks. He sponsored us. Already then, at the age of 11, I felt very deeply Hungarian…

Did this strong Hungarian feeling come from your parents?

Yes. In the Carpathian Basin outside of Hungary, people often feel more Hungarian because their identity is constantly threatened. As a child, Slovak boys attacked us more than once because we wanted to skate on the same lake, for example. When you get into situations like that, it either weakens your Hungarian identity, and you get assimilated over time, or to the contrary, it strengthens your Hungarian identity, and you become a proud Hungarian. The latter happened to our family. My parents, my four siblings, and I always spoke Hungarian at home, and we didn’t know English at first. When we lived in Rome, I always wanted to return to Hungary…

I suppose you joined the local Hungarian scout troop right away…

At that time, there was no Hungarian scouting in San Francisco, but as soon as the idea of founding a local scout troop came up a few years later, I joined them as a patrol leader up front, even though I had never been a scout before. I thus became a founding member of the local troops, together with Tamás Csoboth and a few others. That’s how the Girl Scout Troop Losárdy Zsuzsanna No. 43 and the Boys Scout Troop Béri Balogh Ádám No. 77 were established in 1969. The team grew quickly, but the headcount fluctuated a lot. When I became troop commander, there were already about 50 of us. But there were also moments when it was questionable if we’d survive due to low enrollment. When the troop was growing, it was usually because many new people arrived from Hungary, and they were looking for a Hungarian community for their children. Nowadays, the local troops are very strong and stable, with more than 75 people; sometimes, they have to even refuse applications because there aren’t enough vacancies for new members.

When I got married and my sons were born, I stopped scouting, but by the time the boys became 5–6 years old, I started taking them to the Hungarian kindergarten, where I was quickly asked to become a kindergarten teacher and then to scouting, where I became active again. My adult scouting career lasted about 25–30 years overall, during which time I always served in leadership positions. In 1984 I became a troop commander in San Francisco. In December 1992, when my husband got a teaching job at Columbia University and we moved to New York City, I was asked to take up the district commander’s role there, which I accepted, and thus my relationship with the San Francisco Scouts was less strong for a while.

Before we go any further, tell us, how did you become a family?

After high school, at the age of 18, I spent two years in Leuven, Belgium, where I realized that I didn’t want to be a medical doctor after all, as I fell in love with the French language and literature. At first, I thought of becoming an interpreter, but then I realized I didn’t want to spend my life repeating what other people said. After I came back to California, I attended Berkeley University for two years, and then I studied for one year at the Sorbonne University in Paris to strengthen my French. I met my husband after I moved back to California for the second time.

How did it happen?

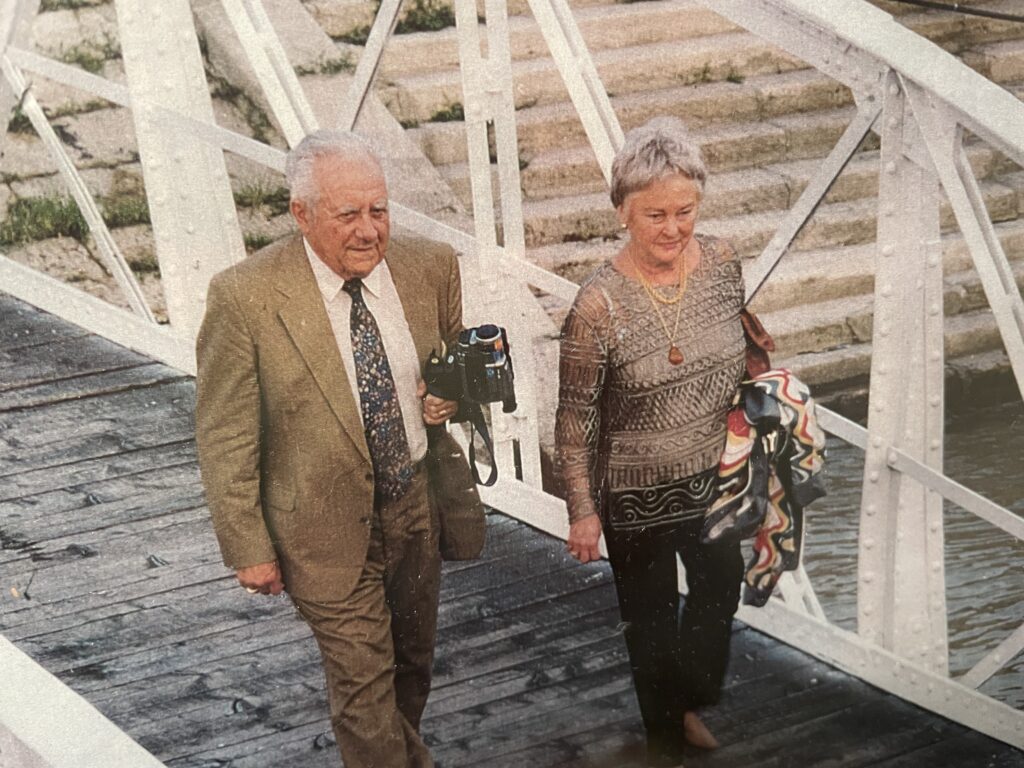

One of the members of the Eszterlánc Dance Group was recruiting as many new people as possible. One day, that member called me and said he’d met a young Hungarian man who was a good dancer and was interested in joining our dance group, so I should call him because we both worked at Berkeley. I was reluctant because I didn’t like to approach boys, but I finally called him and found out that he was an assistant professor of physics at Berkeley, where I was an assistant professor of French. We arranged a meeting, which eventually turned into a marriage… Miklós Gyulassy wasn’t so much interested in the dance group but in meeting girls. I was the bait, which I wasn’t aware of at the time… He was indeed a good dancer and had joined a dance group before, but his job kept him from continuing, and he didn’t join Eszterlánc for the same reason. His mind was always on physics. When I later asked him about our own children’s performances, he replied inattentively that he liked it very much, but then I saw him drawing all sorts of formulas on his napkin…

How did the Kodály Weekends begin?

Everything I’d learned through scouting, I tried to pass on to others. I had a very good friend, Mária Farkas, who lived in California for two years and taught the Kodály method at a university there. We used to sing a lot together, and after a while, I thought, why don’t we organize a weekend program where we teach children to sing in two parts? The first time, we had 20 children come along, and everyone was doubtful about how boring it would be to sing together for a whole weekend… That’s how the first Kodály Weekend took place in San Francisco in 1988. It went so well that we repeated it several times. When I got to New York in 1992, I noticed that while in California, we were very happy to get together with the other scout troops who operated 7 or 8 hours drive away from us—at that time, the highway between Los Angeles and San Francisco had not been built yet—the three troops in the New York area (those in New York City, Garfield and New Brunswick, New Jersey), which operated much closer to each other, maybe an hour’s drive apart, were constantly competing with each other, there was no harmony between them. As a district commander, I started thinking about joint programs where they weren’t competing, only enjoying each other’s company. This is why we organized various folk programs, one of which was the Kodály Weekends series. In the beginning, children always asked: ‘Who won?’ My answer was: ‘All of you. It’s a wonderful experience where everybody wins!’

How can we imagine a Kodály Weekend?

First, we just sang, preferably in two parts. This caused a little debate with Gábor Bodnár, the founder of the Hungarian Scout Association in Exteris (KMCSSZ), who said that Hungarian folk songs are monophonic, so we shouldn’t make them polyphonic. And I told him: ‘Look how beautiful Little Duck Bathes (Kis kacsa fürdik) is in two parts; why shouldn’t we sing it like that?’ When polyphony was developing in medieval Europe, Hungary was at war with the Tartars and the Turks, and survival was more important than polyphonic singing. The great gift of Bartók and Kodály is that they introduced polyphony into Hungarian folk songs in the early 20th century. There are Hungarian folk songs that are beautiful in their monophony and don’t need more than one part, but a well-done polyphonic folk song is a true miracle.

It was during this debate that the first Kodály Weekend was launched, and it was such a success that it swept the debate away. The first time, it was so very cold, and the icy roads were so dangerous that the original plan—to go to the Hungarian Farm in Pennsylvania—had to be cancelled, and we met instead at our house. Thank God, we had a house big enough to fit us all in two rounds: one weekend for the under-12s and the other weekend for the over-12s. Some of the children only had a place to sleep under the table, but that’s no problem for the scouts; going to bed and waking up together is great for community-building, as is singing together. I can’t tell you what a wonderful experience it was when the New Brunswick singing group of 20-something young people sang so loudly that the whole neighborhood heard them. It was a huge job, but also a magnificent experience…

Nourishing Hungarian folk culture is strong in New Brunswick, NJ with several folk dance groups, but I guess others were caught up in the spirit of singing, too…

Yes, singing in a choir is very captivating. If I start singing something and then another solo comes in, the result is something beautiful. That’s what I’ve tried to get the children to do, insisting on signing in two parts. We learnt a lot of monophonic folk songs, but we also taught them three or four polyphonic songs, which they loved so much that we repeated the Kodály Weekends every year. In the beginning, there was no specific theme, but we always tried to organize it in a playful way. In scouting, the story framework is always very important. For us, the regular story was that Bartók and Kodály were collecting folk songs, and they asked the scouts to help them, i.e. they too should go to the villages and collect folk songs. We set up the room so that the children could pick the folk songs from the ‘bushes’, and our living room was the ‘Music Academy’, where they had to listen to the songs on tape recorders and put down on paper the missing lyrics. It happened several times that Kodály and Bartók brought home incomplete folk songs, and afterwards, they spent years searching, visiting villages again, looking for people who might have known the missing lyric We tried to include games and anecdotes, which gave a special flavor to these weekends…

When did you start using instruments?

When Juci Tiger took over, she came up with the idea of not only singing but also playing the flute. At first, I didn’t think a weekend was enough for both, but eventually, I agreed to give it a try. During my years as a troop commander, if someone had a good idea, I always took it up, even if I thought otherwise, because, who knows, it might work. The flute worked. So much so that it has since become an integral part of the Kodály Weekends, where now every child gets a flute and learns to play it. It’s also a wonderful feeling that while one group is singing, another is playing the flute, and a third is doing something else, like handcrafts, so that the whole area is filled with music and something exciting is happening everywhere. At the last Kodály Weekend that I organized on the East Coast, I also invited performers who were playing instruments. Three or four of them came and showed their instruments to the children in a playful way. This was such a great success that I felt almost overwhelmed with happiness.

Why last? There have been Kodály Weekends on the East Coast ever since…

Because we moved back to San Francisco nine years ago. My original plan was to also bring back the Kodály Weekend concept to San Francisco because it had stopped while we lived in New York, but because of work and my grandchildren, whom I love to spend time with, I kept delaying to organize one. But then I was approached by the local troop commander, Etelka Keszei, who said that she’d organize the children if I organized the program. So, in October 2024 we had a Kodály Weekend in San Francisco again. We’ll see if it becomes an annual tradition again. The scout troop’s calendar is very rich, but Etelka said we’d continue at some point since it was so much fun. My one-and-a-half-year-old granddaughter took part because I had to take care of her, and afterwards, she hummed for weeks: ‘I had a goat, you know…’ (‘Volt nekem egy kecském, tudod-e…’) Children were touched by all the rhythm exercises and solmization; they really got it.

How do you feel about the Kodály Weekends continuing?

I’m very pleased that although we left New York nine years ago, Kodály Weekends have been organized there ever since. I’m very happy because it’s a very positive experience in scouting as it is a program where we create something together and there are no winners and losers. We can thank the continuing of this tradition to Juci Tiger, who took over from me as District Commander, to former District Commander Tamás Marshall, and current District Commander Tamás Schachinger. And, of course, all the local team commanders who continue embracing it.

A new instrument appeared on this year’s application form: the violin…

I wasn’t aware of that. At first, I was even worried about the flute, because it costs money. In the meantime, I found out that plastic flutes that cost a few dollars sound nice as well. I can’t imagine a violin for the time being unless there are members of the troops who have their own violins, because while a flute is good for all sizes of hands, a small child uses a completely different-sized violin than an adult. It’s a great idea otherwise since the more instruments, the better. For example, at last year’s Kodály Weekend in San Francisco, I was asked if it was possible to bring a ukulele. I said yes, so we had a group of 5–6 children who played the ukulele.

We haven’t talked about the teachers yet. How did you manage them? Or all teachers and scout leaders can sing and play the flute?

We usually involved those Hungarians who lived in the area and could play the flute. Last year in San Francisco, I involved my own children, as well as troop commander Etelka’s son Döme. We usually invite older scouts, but when there weren’t enough scout flutists, we invited non-scouts as well. I know that in many places there are unqualified teachers. This time, I had my friend Jutka Kádas, who graduated from the Academy of Music in Hungary, and for 25 years, she taught children to sing and play the flute and the piano. I invited her to work with the younger ones, and you could immediately feel that she had a knack for it right from the moment she stood up in front of the group. It’s quite different when you have someone in control who knows how to teach and how to correct the teachers, who is able to tell them that we don’t start a four-beat song with a one-two-three, for example. It’s very important to have at least one person who knows how to deal not only with children but also with music and choir.

Why did you move back to California?

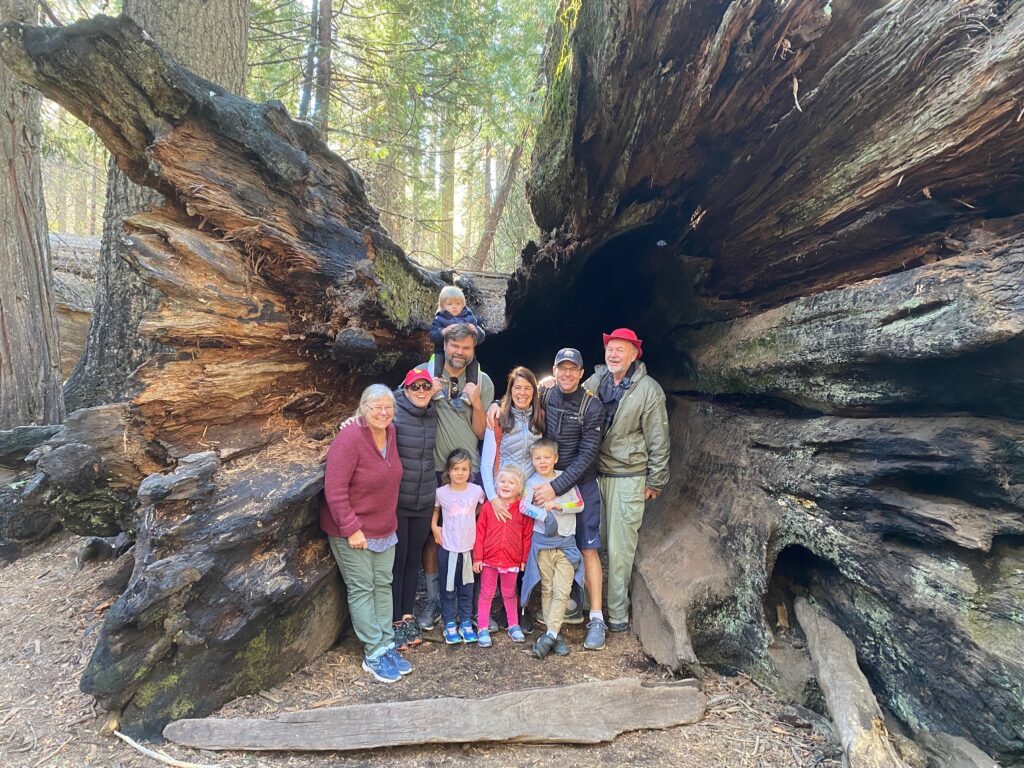

Laci was then 13, Attila 12 and Kati was four when we moved to the East Coast. Our sons were always very determined to study at Berkeley; they weren’t interested in any other university. Our daughter also moved back, and she went to an art school in San Francisco. We later followed them. But they went back not just for the university but also because there were a lot of cousins living there. Our family is very big: I have four siblings, and they have three to six kids each, so it was a lot of fun for our children to come back. Of course, not everyone lives here anymore; many have dispersed, and some have gone back to Europe, but there’s still a close bond between them. We also love the city itself, and the nature is beautiful. We can go skiing, and then in four hours, we can swim in the Bay on the same day…

What do your kids do? Do they have families?

Laci has a veterinary clinic, an American wife and two children who speak Hungarian because I took care of them for a long time when they were little, but when they started school, the Hungarian bond got a little loose, and now they don’t speak Hungarian perfectly anymore. Their mom insists on having them with her on weekends, so they don’t go to Hungarian school or scouting. But on Mondays, they are with me, and the rule here is: there is Hungary at grandma’s house. Whoever speaks English gets a point every time. Whoever gets three points has to learn a passage of a poem in Hungarian. So now they blow a lot of poems by heart… But of course, they also get rewards: if they speak Hungarian nicely among themselves, remember the collected Hungarian proverbs, or read in Hungarian, they get tokens which they can later use at the yearly garage sale I hold for them for this purpose.

This is a scout idea. Do your other two children also have a bilingual family?

Yes, all three of my children have American spouses who aren’t opposed to speaking Hungarian; in fact, they are happy for the children to be bilingual, but they obviously cannot help with the language. Attila is a mathematician who works with data visualization and editing programs that extract useful information from a huge amount of data. This can be used in many fields, for example in oil research or cancer research. His three children speak Hungarian. And he recently started to get them into scouting, just because of the Kodály Weekends, because he saw what a wonderful loving Hungarian environment they were getting into. The fourth one is on the way there, so I really hope he sticks to this idea.

My daughter Kati is an artist, a ceramist and a painter. She lived for a while in Utah, where there are festivals every year in Park City. After a few months, she had to decide whether to stay there or return to California, but because of the COVID-19 pandemic, she got stuck there with her boyfriend, who became her husband, and now I have a granddaughter there too. Her husband has started learning Hungarian, and now he understands most of what we’re talking about. They are planning to move to Hungary for two years, but currently, they are living near us, and I’m looking after the little girl while she is painting. It makes me happy that my children insist on being Hungarian. They all have Hungarian passports, so they are officially part of the Hungarian community.

‘You know, Mom, I still live by the Ten Scout Laws’

How active are they in the local Hungarian community?

They were all scouts, both in New York and San Francisco, but when they went to college, they couldn’t continue scouting anymore because they lived at least two hours’ drive from the scout home. Today, they are not active at all. Laci doesn’t have time; he works very hard, often on Saturdays too. Attila might become more active later, but for now, he prefers to help at home. One of my grandsons, András, had a patrol leader at the most recent Kodály Weekend, who visited this year’s Jubi Camp and told everybody about how fantastic it’s to live in the forest for 10 days and build all kinds of things. My grandson told me after the Kodály Weekend as he walked in the door: ‘Grandma, I’m going to Juli Camp! You know, the one where they build things in the woods…’ I explained to him that it’s Jubi, not Juli Camp and is made up of other things, too, and that it only takes place once every five years, but he was very enthusiastic at the time. Over time, of course, this influence wore off. Her mom is not keen to let the kids go on weekends either. Just recently, my son told me: ‘You know, Mom, I still live by the Ten Scout Laws.’ I replied: ‘Very good, you just need to pass it on to your kids…’

And what about your extended family, do they volunteer?

My siblings sometimes come to a Hungarian event, but they aren’t active in the Hungarian community. They were older when we started scouting in San Francisco, so they never scouted themselves; it was only me. But they are helping in other ways. One of my brothers is trying to build a start-up program in Hungary.

You were a dedicated scout for so long. Nowadays, I understand you’re doing less community work to spend more time with your grandchildren.

That’s right. I’m not so much needed in scouting right now. Very clever folk games are organized by a KCSP scholar, Gergely Bolgovics. I really like the fact that he doesn’t teach folk dance to 6–7–8-year-olds, but only folk games, which, of course, include dance steps at their level. This will develop the movement needed for folk dance later, but he doesn’t teach whole choreography to young children. They rotate, they spin, but the emphasis is not on two to the right, two to the left…

What’s the right way to teach flute? We met at a conference at the Meeting of American Hungarian Schools (AMIT), where you were teaching flute.

Yes, that’s what they asked me to do. Since I knew that there would be teachers who hadn’t played the flute in 15 years and some who had never held a flute in their hands, I thought about how to simplify teaching the flute in a way that no one would be afraid of it, they would dare to pick it up and also have a sense of achievement at the end of the class. Before the AMIT conference, I tried it with children: I drew five lines on the blackboard, put a violin key on it, and thus we had sheet music. I showed them the sounds in five minutes, and they could read music very quickly. Afterwards, I showed them the notes on the flute. I explained in a similar way to these teachers at the conference, where we also played a little game with the notes. A couple of weeks ago, Eszter Gagnon, one of the organizers, informed me that two teachers had indicated to her that although they couldn’t play the flute, with my method they started to teach it at their Hungarian weekend school, and one group of children had already performed a flute number as part of their Christmas program last year. That’s exactly what I tried to convey to the participants at AMIT: you can teach the flute, even if you can’t play it. I know someone who can’t play the piano but teaches it. This method was invented by a Hungarian teacher who taught the Kodály method. A friend of mine who couldn’t play the piano studied it, and she’s been teaching piano for a living ever since. So, the main message of my lecture at AMIT is that even if you don’t know music, you can still pass on how to play the flute. I’m not a great flute player either; I rarely use it, so I had to practice it before the AMIT conference. It’s wonderful about music that you don’t have to be an expert to pass it on!

Read more Diaspora interviews: