Father Iván Csete has often talked to me about his friend László Oroszlány and has invited me several times to visit the (non-Hungarian) church in Port Jervis (in upstate New York, where the borders of three states—New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania—meet), where he celebrates Hungarian mass once a month for ‘his Hungarians from the Highlands’. We managed to get to them on the first Sunday of January, but since László had previously sent me his memoir (My Life: The First 83 Years), in which he summarized his adventurous life story, I ‘only’ asked him questions that had occurred to me after reading it.

***

‘Man plans, God decides’ is the most common sentence in your book…

Yes, my life very often turned out completely differently than I had planned. History intervened several times; for example, World War II, the final phase of which I experienced in Hungary as a child aged 8–9; the communist dictatorship that followed; and then, the 1956 revolution and freedom fight and its suppression that I had to flee from. Then an accident, which left me and my brother Toni stranded in Italy, forever missing our flight to Canada, after which we could only immigrate to the United States, and which caused me to lose my first love, Anna. Much later, due to an illness I lost my first wife, Kati, after 32 years of happy marriage. And finally, a primary school reunion in Hungary led me to my second wife, Ani, who moved to the United States to live with me 20 years ago…

That’s why I often tell young people: Don’t be upset if something doesn’t work out, look at my life: it may have been better or worse than I wanted; but I’d miss a lot if it had been different, and I certainly wouldn’t want to trade what I have for anything. After all, if I had something different in my life than what I actually experienced, it would mean that I’d not have possessed or lived through what I actually have, and I don’t even want to think about that… Last Thanksgiving it was the 68th anniversary of our arrival in Italy, so I asked my family—ten Oroszlánys were gathered for dinner and I was the most senior family member—to give me a little more time to speak. I told them that I didn’t want to leave my country at all and I certainly didn’t want to live in America, but I thank God that my life turned out the way it did and that I have the family that surrounds me now. If it hadn’t been for that, they wouldn’t be either. My brother’s family would be quite different, and the same can be said about the 17-year-old girl with whom we parted ways for good in Italy.

Your family was on the ‘kulak’ list, so you couldn’t attend high school. You moved to Budapest and went to a technical school after work. In Italy you learned Italian, in America you went to university. What drove you not to give up and keep on studying?

Since I couldn’t go to high school, I just wanted to study, it didn’t matter what.

Before I went to the technical school, I took different courses. For example, I’m a certified welder, although I have never actually worked in such capacity. I also went to a flying club, even though I couldn’t have been a pilot. I’ve loved learning all my life—up until recently, because my brain is slower now at the age of 89… Other than that, I loved mechanics and precision work, I was a handyman to my father as a young child. I loved fixing things at home: I straightened nails, carved a sledge for myself, and if I didn’t have a tool, I’d watch the blacksmith to learn how to make one. I worked and studied in Budapest for seven long years, while I didn’t have much time for fun or making friends. In America at 22, I applied to university because I wanted to develop myself and achieve something more. When I met my first wife, I was just a mechanic in the eyes of her relatives, but when we got engaged, I was introduced by them as a chief engineer. I was neither…

You became a successful engineer, while you remained attracted to music…

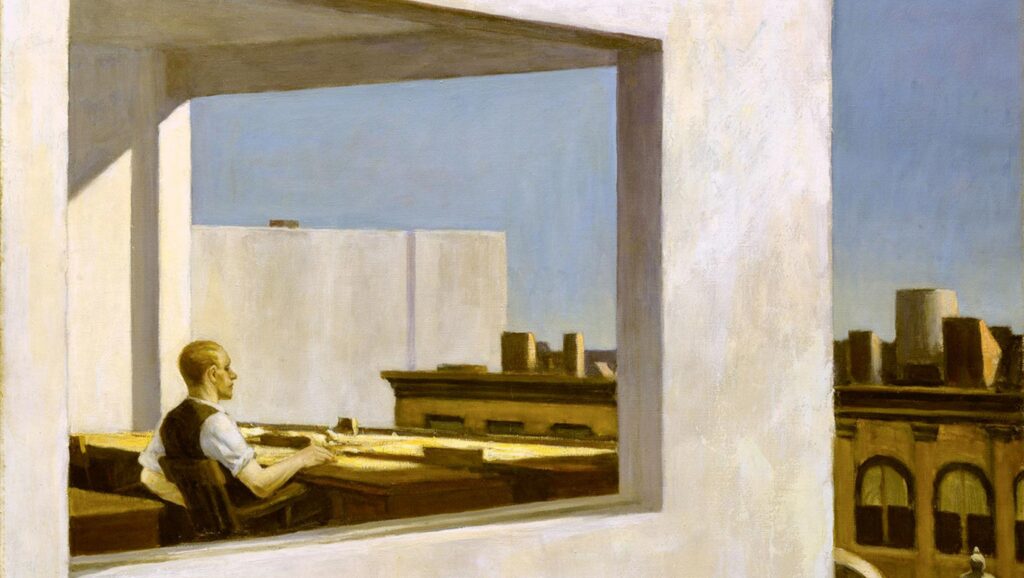

Hundreds of small companies participated in the Apollo space program as suppliers, including my company, Apollo Machine Shop, founded in 1966 which operated for nearly 42 years. It never became a big company, but I’m proud of it, since not many small companies have existed in this sector for such a long time…

I always wanted to learn music, I just never had the chance. When I was studying at home in the evenings after work in Budapest, the radio was always on in the background, so I ended up learning a lot about music. When I stayed with the Baron Monti family in Merano, Italy for seven months after my accident, during our regular conversations they also asked me about my musical knowledge. Dr Monti hummed an Italian song I knew, a well-known aria, which I had to write down. He made a small mistake, and I wrote it down with that mistake, and the Baroness was surprised: she said she had studied piano for seven and a half years and had not noticed the mistake… After that, I was even more tempted to stay in Italy with them and study music at the Music Academy there, but I couldn’t accept the opportunity. My brother stayed in Italy only for me, and I wanted to get to Canada as soon as possible to find out what had happened to my love, Anna…

But that’s not ended your ‘relationship’ with music.

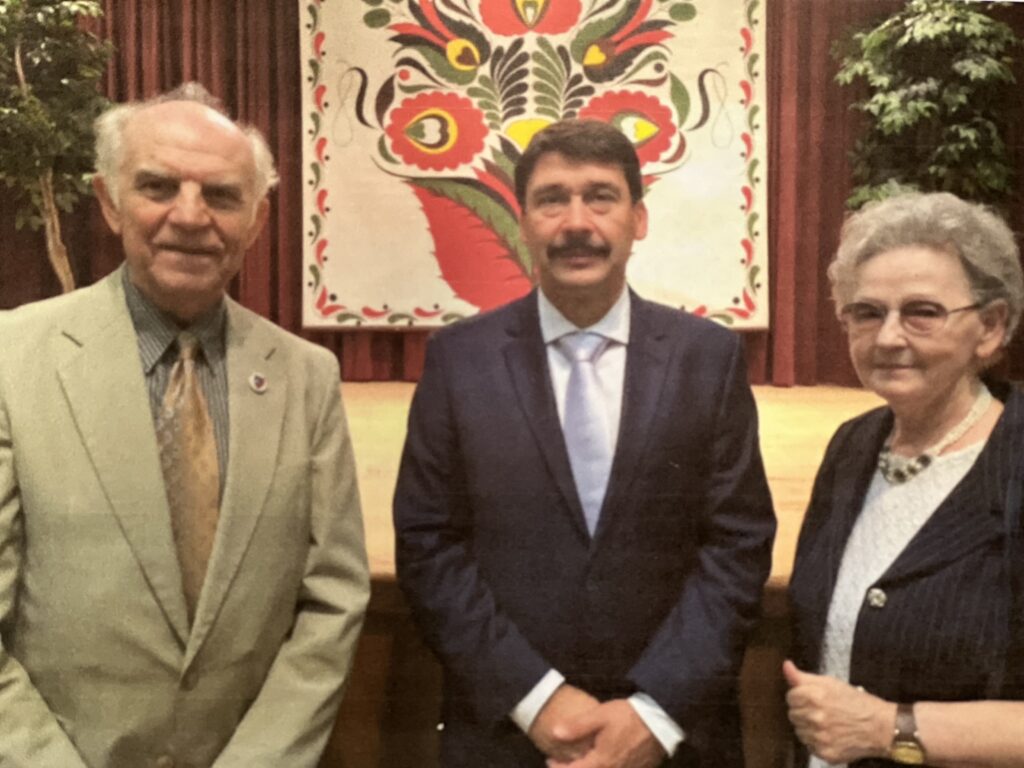

I wrote a few songs, usually for the drawer, but my brother showed one of them to an opera singer in Budapest, Mihály Zsuzsa. He sang the song and said it’s too good to stay in the drawer and I should nominate it for a contest at the Song Olympics held every four years since the 1930s. This was 11 years ago, and since we were in Hungary at the time of the awards ceremony, we attended it. Rozika Farkas sang my song and I won first prize with it, which I was very surprised about. Not long after, in Passaic, New Jersey, Hungarian President János Áder congratulated me for this award. It was a big event for me, because I’d been living far away from my homeland for 55 years. It was a kind of compensation for not being able to study music…

You had previous musical successes too, right?

For 20 years I sang, with Kati, in the famous choir of St. Stephen’s Church in New York, called the ’Word of Faith’ (Hitszava in Hungarian). We performed several times at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and at Carnegie Hall. For some time, our guest conductor was Árpád Darázs, who was the conductor of the Hungarian Radio Choir in 1956. He also emigrated in 56 and lived on Long Island, where he conducted his own choir. He was invited by Róbert Harkai, one of the leaders of our choir, who was also the director of the Arany János Hungarian School in New York and the Széchenyi Society. It is also thanks to him that Cardinal Mindszenty smiled at me, and this has left a lasting impression…

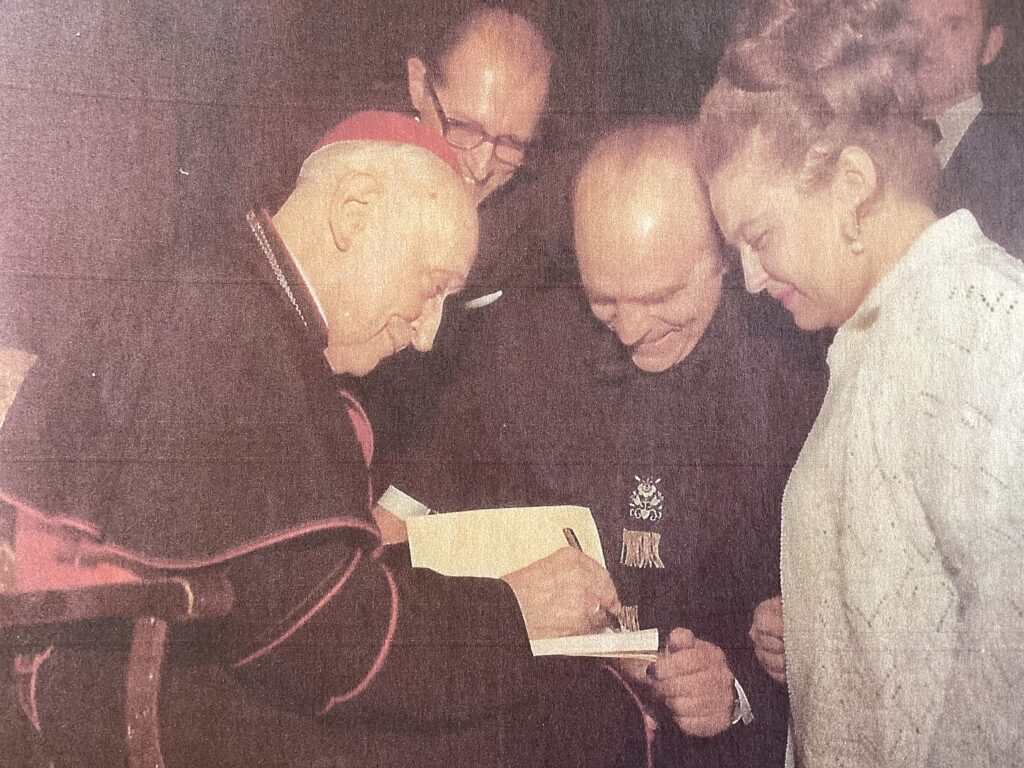

Why, what happened between you and Cardinal Mindszenty?

Cardinal Mindszenty started his American tour at our church in New York, after which a reception was held in his honor at the elegant Hotel Waldorf Astoria, with Róbert Harkai as the master of ceremony, and he introduced us to Cardinal Mindszenty. I don’t think I have ever met a man of greater character than this holy man… I had a book with me and I asked him to sign it for me. He replied that he didn’t sign books, because then other people would want him to do the same. And I jokingly responded: no problem, we’ll form a circle around him so that other people wouldn’t see what he’s doing. He smiled, and the official photographer caught that very rare moment, which I got a photo of and have treasured ever since.

How did you get involved in the Hungarian community in New York?

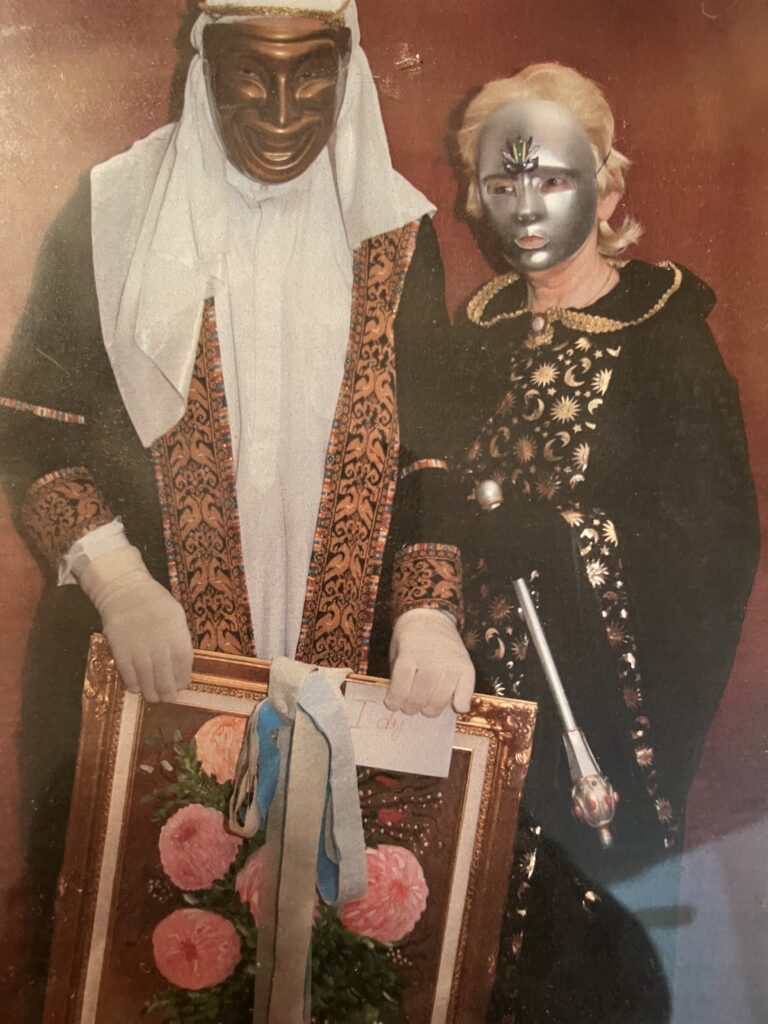

On February 26, 1959, when my brother and I arrived in New York, we found ourselves in a very bad hotel, and the first person we met on the street was a homeless man begging for money from us, the fresh refugees… We left the hotel in great sorrow, and walked up to the Hungarian quarter, first to the Reformed Church on 69th Street. Reverend Imre Kovács only asked us about our religion after talking to us for half an hour, and when he found out that we were Catholic, he insisted that we’d definitely register at St. Stephen’s Church, which we did the same day. Father Imre Slezák was the priest there. At that time, there were a lot of young people around the church and other organizations; there were a lot of Hungarian gatherings. In addition to the Piarist Ball, the only Hungarian ball that still exists today, there were at least four other Hungarian balls in New York during the ball season, where the Hungarian debutante girls—including Kati, my future first wife—were escorted by West Point cadets. The balls were usually held at elegant ballrooms, for example in those of the Hotel Waldorf Astoria or the Plaza Hotel.

That has all changed since then and the choir’s long gone, too. Why? New immigrants have always come to New York, Hungarians included.

First, there was always a problem of lack of parking space in central New York and not everyone undertook to drive to Manhattan once a week and park in a garage for a fee. Secondly, the Hungarian quarter itself has melted away over the past few decades. When we moved here, there were still a lot of Hungarian establishments: three Hungarian bookstores, four Hungarian butcher shops—including my brother’s for a while—, several pastry shops, and at least 15 Hungarian restaurants. But over the last 30–40 years, all Hungarian places have gradually disappeared, except for one pastry shop. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, there was a failure to involve the younger generations… St. Stephen’s Church was built by Hungarians 120 years ago, but shortly afterwards, during the Great Depression, they couldn’t pay the mortgage on the building. They saved the church from closure by having it taken over by the Americans—first the Franciscans, then the diocese. There were Hungarian priests, sometimes even two or three for a long time, but—as I used to say—from then on, Hungarians were only tenants there. And unfortunately, the question for the American Pastor of the parish was not whether he was anti-Hungarian or not, rather how much anti-Hungarian he was. Whether this was part of their own belief system or they implemented central instructions, I don’t know… I also had a serious fall out with Fr. Angelo, when I was member of the Parish Council and chairman of the Lay Committee for several years.

What was Fr. Angelo doing that created such conflict?

Strange things… For example, when Bishop Endre Gyulay visited us at the church, there was a full house reception luncheon in the White Hall for his honor. We waited a long time for the host, the Pastor to come and greet and sit with the bishop up front. But Fr. Angelo came late and didn’t even greet the honored guest. Afterwards I wrote him a letter in English, saying that I was terribly upset about what had happened. I had several people read it before I sent it. In response, I received a very harsh letter from him stating that he couldn’t work with me and that he was going to replace me in the Lay Committee—he couldn’t do it as it was independent of the church, but it was a very unpleasant time. As was the fact that he shouted at me in the rectory afterwards. Half an hour later he approached and told me: ‘Laszlo, you do so much for this church…’

In the early 2000s, a group of young people around the church organized a Hungarian club on Fridays, and there were times when 50 people came together at their events. In the beginning, Fr. Angelo was very friendly with them, and for a while everything went very well. They could play table tennis in the main hall, and there was even a small room next to it, where they organized creative events of high quality. But then he rented out the halls for others and the young people couldn’t have their Friday night events any more. The last big event they organized was a carnival with a huge success. Then there was a Hungarian street fair in front of the church and Fr. Angelo angrily shouted at vendors and organizers questioning what they were doing there, and one of the organizers shouted back at him, and never came back to the church again.

Fr. Angelo rented half of the choir loft out to the school, which became their storage room, so we couldn’t go upstairs where the choir used to be, and we couldn’t use the organ either, the cantor had to use the piano downstairs. I don’t know if it was just due to his erratic behavior or if there was another reason… Perhaps the church was already expected to close and in the background nefarious deals were already being made about its fate. It was built on a very valuable piece of land, so we also suspected that there might have been a financial aspect behind the closure. I don’t know the details, because they obviously had no interest in communicating clearly with us, but it seemed as if they didn’t want to keep the Hungarian church. There is no longer a single Hungarian Catholic church in the whole of New York State. Before that, there was one in Yonkers, NY, too. We attended its closing mass, and I even spoke out and asked the parishioners to come to New York afterwards, because if we don’t have enough attendance, we’ll also be lost over time; which, unfortunately, happened.

What could you do about it as a member of the Parish Council?

With a business and a family of my own, it was no small sacrifice for me to go to the Parish Council meetings in Manhattan once a month at 7pm; but I was always there, and I always looked for the opportunity to make a difference in Hungarian affairs. There were many more Americans than Hungarians on the council, and most of the time I was the only Hungarian who spoke. American members of the Parish Council were generally interested in what I was proposing. For example, I remember once we were in Hungary in the winter, and in the two-towered Rókusi Church in Szeged, the priest wore ear protection, because it was so cold—even inside the building. When I told them about it at the next meeting after my return, they started laughing. Then I asked them to think about the conditions in which people go to church in Hungary… This changed the whole mood of the meeting, and they even wanted to start fundraising for that particular church. Only the parish priest, Fr. Angelo, was bothered by the fact that I often spoke and I always spoke about Hungarian topics.

Which reminds me: before that, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the 56 revolution, there was a serious disagreement within the church…

Leading up to the anniversary in 2006, 49 people representing practically all of New York Hungarian organizations, both church and secular, formed a 56 Committee in New York. There were quite a few of them, with different religious, political and ideological orientations, including one of the last Hungarian Catholic priests, Father Domonkos, who, if I remember correctly, even donated one or two thousand dollars for the committee. When he returned to Hungary, two young Franciscan priests came to serve one after the other. We warned the first one, Dénes Hess, but the result was that everyone was on the 56 Committee, except for the representatives of St. Stephen’s. And while we were celebrating in Carnegie Hall with a beautiful memorial service and concert, there was a ‘counter-celebration’ organized in the White Hall of the church, which caused a great rift in the community and the number of mass attendees never went over 100 again.

What happened afterwards?

Father Dénes served here from 2006 to 2009. Only a month after his arrival, another young Hungarian Franciscan priest, Fr. Ágoston came here to study in New York, and also served at our parish. From the beginning he was a lot more popular than Fr. Dénes, liked by young and old. But our pastor, Fr. Angelo declared him ‘persona non grata’ and he went to Washington, DC, continuing his studies there. He also became the Hungarian priest there, though there is no Hungarian church there. Since Fr. Dénes went back to Hungary in 2009, there has been no resident Hungarian priest at our Hungarian church, only one Hungarian mass on Sundays at 2 in the afternoon, thanks first to a Polish priest, Fr. Pawel Cebula, who earlier lived in Hungary and spoke our language. That time he was stationed in Connecticut, about an hour and a half from New York. He gave up his free Sunday afternoons to serve us. After being sent back to Poland, our Sunday afternoon mass was done alternatively by two Hungarian priests who came from Passaic and New Brunswick, New Jersey, Fr. László Vas and Fr. Imre Juhász respectively. Fr. Iván Csete joined them, coming from even farther away, from Forestburgh, New York. Fr. Vas died quite young and unexpectedly and he was followed by Fr. László Balogh. Since Father Laci moved back to Hungary last year, Father Imre and Father Iván rotate. They all gave up their free Sunday afternoons to serve us…

What could you do for the church as Lay Committee President?

For quite a few years I was the vice chairman of the Lay Committee founded by Róbert Harkay. When the chairman fell ill, I took over for him for a good three years. Not only did I write the weekly newsletter, but I also paid the printing costs. I don’t claim any credit for that, but it bothered me seeing someone offer a dollar for the offertory at mass. Then I’d rather donate nothing, since that’s far from enough to keep it going… The community offers time and energy, some offer more and some less, but those who have more should give much more, not just a dollar. We also have supported various organizations, including non-church organizations. Dr. Eleonor Kelley—an American with Hungarian roots (her mother was from the Highlands, i.e. today’s Slovakia)—was a member of our choir for a long time and after her husband’s sudden death, she set up a Hungarian foundation, the Hungarian Christian Education Fund (HUCEF), with a million dollars, for many years sponsoring students from Hungary to America for six months to study. We also became members. In 2002, at the meeting of the organization in Washington, DC, I received a medal for my support of the Hungarian cause, which was presented to me at a reception by Géza Jeszenszky, the Hungarian Ambassador to the United States at the time. I jokingly remarked to him that this Kossuth Medal was as valuable to me as the Kossuth Prize could be to someone else in Hungary.

As far as financial support is concerned, sometimes you have to open your wallet for the community. I have never had deep pockets, but when my first wife died, her name was put on a plaque in several churches. Even in Hungary, where my brother lived and a church had been built nearby, there is a Memory of Catherine Oroszlány plaque on the altar. In Budapest, in the 17th district, there is a 56er statue, which my brother and I donated to—I didn’t remember that until we attended the unveiling event, and saw our names on the back of the statue.

Finally, tell us about the Hungarian community in Port Jervis, NY.

Up until 2015, Father Iván Csete still had the (non-Hungarian) church where he served as the Pastor of Saint Thmoas Acquinas church in Forestburgh, New York. When in 2010, Ani and I moved to our present home in Pennsylvania, near Port Jervis, NY, we started going there every first Sunday of the month for a Hungarian mass and also helped to clean up the yard around the church. And when that church was closed, the parish was still in operation for a few months, so we cleaned out one room and turned it into a chapel where we had Hungarian mass on the first Sunday of every month. I think Father Csete celebrated masses there on other occasions, too, and not only for Hungarians, but he could only use it for a short time, because that building was also sold. They closed it and they even took away the key and wouldn’t even let us go in… It was also very ugly. After that, Father Csete moved to a monastery house for six months. From there he drove here to Port Jervis, and from the train station he traveled to New York City every second week to celebrate the Hungarian mass there. During that time, Cardinal Péter Erdő told me when we met in Washington, DC: ‘Now you have a Hungarian priest to say mass to you in Hungarian…’ I didn’t have the opportunity then, but I later explained to Bishop László Kiss Rigó of Szeged that it was almost like someone from Győr, Hungary would want to travel to Makó, Hungary every Sunday afternoon to say mass, i.e. three–four hours of driving one way. The bishop looked at me in shock. This is also hard to forget…

Going back to this church in Port Jervis…

Shortly after Father Csete started to take the train to New York City on Sundays, he was looking for a parking lot in Port Jervis, NY, so he entered the Catholic church to talk to somebody about it. The very sympathetic parish priest not only said yes to him, but offered him the opportunity to move in here because it’d be easier for him to travel to New York City regularly from there, and he could possibly help him out with celebrating masses as a resident priest, too. He’s been living here ever since. Except for a short period when several parishioners from St. Stephen’s Hungarian Catholic church in Passaic, NJ also came to attend the monthly masses here, and the period of the Covid pandemic when many parishioners passed away or moved out of the area, our numbers haven’t changed much, hovering around 25–35 per mass, but unfortunately we are all getting older and new people rarely join. During the past few years, Zita has been cooking, Zoli making the coffee and Erzsike creates and brings the cakes. Father Csete still helps out in his old church, for example he is still the pastor of the firemen’s brigade there and goes to their meetings, and still visits New York every other week. We are worried about how long he will last, since he is also almost 90, and has serious health problems, too.

Read more Diaspora interviews: