Zsuzsa has lived most of her life in Hungary, while Gyula grew up in the United States. They have known each other for only about 15 years, but since their first meeting in Budapest they have been driven by common social goals: strengthening cultural and economic ties between America and Hungary through their leading role in the American Hungarian Federation (AHF) and the diverse agricultural, innovation-related and cultural activities of the Americans for Hungarians Foundation (Amerikaiak a Magyarokért Alapítvány), which they founded together.

***

Zsuzsa, tell us about yourself, Gyula, and your life before America!

Zsuzsa: I had initially HR roles in different state institutions and later became a jewelry trader first through a company in Szeged. Then I went solo and became one of the biggest jewelry wholesalers in the country. I was blessed with a trader’s mentality, but that all changed when I moved to Budapest in 2005 and started a completely different phase of my life. For six or seven years I ran the Hungarian Service Foundation and the Panorama World Club together with László Tanka. In the former, I was involved with Hungaricums, while in the latter I organized four so-called World Balls. What motivated me to make the switch was on one side to help Hungarians living around the world in every possible way; on the other, the sudden death of my husband in 2003, at the age of 45, due to complications originating from childhood diabetes, when we didn’t even get to say goodbye…

How did you meet Gyula?

Zsuzsa: We met through intermediaries, Erika and István Fedor. I was the master of ceremony at the World Balls; I went to every table and greeted everyone warmly. In 2007 Gyula was also present, but I didn’t remember him. In 2008 Erika suggested I meet him, because he’d suit me very well. I didn’t take it seriously as I was never motivated in my job to find a husband. But in January 2009, Erika reminded me again that Gyula would be coming to Budapest from Vienna soon, and I could meet him for coffee. When I asked how I’d recognize him, the answer was: watch the video of the ball, he was sitting at our table. Since no one had called me by 11am that morning, I called Erika and found out that Gyula would be coming a week later…

It doesn’t sound like smart matchmaking, but it was a success in the end.

Zsuzsa: We finally met a week later and talked for more than two hours. After that Gyula came to Budapest several times, but already at the third meeting there was no question that the chemistry worked between us. And at the very first meeting, we started a joint ideation process that was surprising for both of us and that has continued until this very day. At that time, Gyula was involved with the American Hungarian Federation (AHF), where he had already played a major leadership role. When they celebrated the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the organization in New Brunswick, New Jersey in 2009, Gyula asked if I’d attend the event with him. It was then that I got to know the organization. We married in 2013, and since then—and in reality even before—we have become inseparable also in our voluntary work. In 2009 we started the American Hungarian Club, which in 2010 became the Americans for Hungarians Foundation, with the aim of improving relations between the two countries.

Before we go any further, let’s give the floor to Gyula, who carries on a very strong family legacy.

Gyula: I was born in Hungary in 1944, when Americans were bombing Budapest. Only my sister managed to escape to Austria with my parents; my godfather took me after them later. We lived first with relatives in Vienna, then in Munich, Germany for seven years in total; I finished second grade there. My father worked as an interpreter for the US Army—that’s how we managed to get to the U.S. in 1952. I went to the Piarists in Pennsylvania, then studied physics at the University of Notre Dame, then engineering at New York University, and finally an MBA in finance at Columbia University. I worked for over 20 companies; my first real job was at IBM, developing the first computer based time-sharing system, the precursor of the internet. During the Vietnam War, I was offered a job to work for Boeing Aerospace on radar detection for missiles, and then I worked in Haskins Labs, developing computer reading machines for the blind. Later, at Citibank, I developed the credit scoring systems that are now commonly used, in addition to all sorts of other new consumer financial products.

What about your family legacy?

Gyula: My father, Dr. Elemér Balogh, was very much involved in Hungarian American affairs for 40 years. He participated in the founding of the Hungarian House in New York City, and founded one of its owners, the Széchenyi Society. He was also actively involved in restarting the elegant Piarist Ball in New York City. As a child, my father wanted me to get involved in Hungarian matters—that’s why he sent me to Hungarian scouting and to study with the Piarists in the U.S. I also had to go to all sorts of Hungarian events, like formal balls, although I wasn’t enthusiastic about those. But Viktor Fischer, the former scout troop commander in New York, was a good friend of mine, and I was happy to help him organize sports competitions, for example. The Piarist Ball was on hiatus for a long time. Eight years ago, Tamás Hilbert asked me to help him restart it—I was the only former Piarist student he knew—and we managed to re-start the ball.

Zsuzsa: Gyula’s father was a very committed Hungarian. He arranged, with the help of Barbara Bush, for the Institute for the Blind in Budapest to be returned to the Church for the nominal ‘sales price’ of one forint. But the reason they had to flee Hungary is the maternal side, which Gyula doesn’t like to talk about…

Gyula: My other grandfather, Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös, was a Hungarian who only looked at what was good for the country. When he became Prime Minister, he made a deal: he would not allow anti-Jewish laws to be passed in Hungary, and in return he asked for the support of Hungarian Jews. I don’t know the whole background, but I was very close to my mother and I understood what she told me about that era; for example, when the persecution of Jews started in Hungary, she, as the daughter of the prime minister, told one of her classmates: ‘Come to our home to live, we’ll protect you.’ In America, speaking five languages, she worked in a chocolate factory. My Dad, who spoke seven languages and had a PhD in Finance, started working for $37 a week. So I grew up among the poorest immigrants. But God has helped us so that at least my children and grandchildren are now living in much better conditions…

Tell us more about them.

Gyula: I have two children from my second wife, Péter and Dani. Péter is a biochemical engineer, receiving his PhD at Rutgers, and is now teaching at NJIT with research using a supercomputer to study human blood circulation. His PhD thesis beat Harvard and MIT and others in a national competition, which I’m very happy about because it’s a rare occurrence. Dani is a veterinary surgeon and has a VMD from the University of Pennsylvania, one of the best veterinary schools in the world. Péter lives in New Jersey—just like us—, and Dani has his practice in Virginia. They are both American and Hungarian citizens. I have four grandchildren. We visited them recently; the children love Zsuzsa.

Zsuzsa: I love them too. I have a daughter who lives in Szeged, no grandchildren. Going back to Gyula’s maternal grandfather, he elevated Hungary’s Italian and German trade relationships in the 1930s–1940s, which still has a lasting impact today. Gyula says that he is bound by his name also on his mother’s side to serve Hungarian causes.

Gyula: Indeed. As for my paternal legacy, a few years before my father died in 2008, he asked me to take over his Hungarian affairs. At first I protested, because I wasn’t involved in them at all before and I didn’t speak Hungarian that well, but eventually I accepted his request. So I became the president of the Washington based Hungarian Reformed Federation of America and its Kossuth House from 2005–2008, my job being primarily financial to keep them going. I’m Catholic, and when I took this on, my father said: ‘Son, finally, you have a decent job.’ Later I became co-president of the AHF from 2010 until 2024.

So it was practically due to your father and then to Zsuzsa that you became involved in Hungarian affairs?

Gyula: That’s right. Zsuzsa and I have been living both in Hungary and the U.S., and at the beginning we were wondering, who can we help? My ancestors’ background is in agriculture. My paternal grandfather created the Hangya (Ant) Cooperatives and ran it for 38 years in Hungary. A good friend and I wanted to help Hungarian agriculture by the robotization of agriculture. There are a lot of very smart Hungarian innovators in America with world-class inventions I know, but unfortunately, they are not sufficiently embraced in Hungary…

Zsuzsa: I was dealing with Hungarians all around the world, while Gyula is an American Hungarian. We wanted to effectively strengthen Hungarian American relations, where his experience and knowledge of America and mine of Hungary combined could create additional value. Gyula’s grandfather, Dr. Elemér Almási Balogh—my husband is actually Gyula Balogh Almási, but he didn’t take the noble name, although we all have the Almási coat of arms on our glasses—was the founder and CEO of the national network of the Hangya (Ant) Cooperatives from 1898 to 1936. Gyula thought he could continue with his grandfather’s work…

Gyula: We first organized a gathering of 500 people in the Senate Chamber of the Hungarian Parliament. Zsuzsa knew most of the relevant people, and the former Parliament Chair Dr. János Horváth helped us. He also awarded me the Újhangya (New Ant) flag. It was a very beautiful scene as he handed it over, encouraging me to carry on this noble family tradition.

Zsuzsa: We traveled the country for five years, reaching 70 cities and villages. In the end, the New Ant Cooperative was established in five cities. In our experience, the biggest problem was that it was difficult for Hungarians to selflessly unite. We tried to explain to them the American cooperative system, such as the joint procurement mechanism, but they generally resisted. Before Gyula tried to implement the American cooperative approach to agriculture in Hungary, he did some serious research on how it works in America, home to 23 thousand cooperatives, which are doing well besides the big multinational corporations—that was his idea and his goal. We asked the government for support, but to no avail. We had some success, but it couldn’t spread across the country.

Many Hungarians probably still associate it to the forced cooperatives of the Communist times and those unpleasant memories may lead to resistance…

Zsuzsa: Yes, the forced and compulsory cooperative system during the Communist time must have left such a deep scar on the Hungarian consciousness that the old-new cooperative system that we advocated for couldn’t spread. And the reason for the lack of governmental support is that at that time Auchan, Tesco and other retail chains solidified their presence and control over the agricultural supply chain whereby their products were given priority, completely marginalizing Hungarian farmers, who, despite having produced fairly and healthily, had often reached the point where it no longer made sense to farm at all. However, the question keeps lingering: how to restore the cooperative system? Miracles may sometimes happen… But when we tried, the circumstances were not favorable at all.

Have you had more success in strengthening US–Hungarian relationships?

Zsuzsa: Yes, although we had mixed experiences in that space, too. We had a lot of business contacts in America and Hungary whom we managed to cooperate with. On 23 November 2009 the opening ceremony of the Hungarian Club of America—the predecessor of the Americans for Hungarians Foundation—was a success, with 250 enthusiastic people attending the event in Budapest, where 15 Hungarian and American organizations were present. The theme of the evening was the message President John F. Kennedy addressed Americans with a few decades ago: ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.’ Later, we delved into the life of the AHF, of which Gyula became co-president of. We organized the 110th and then the 115th AHF anniversaries, which were challenging for me because I didn’t know too many people at first. For the latter we brought world famous singer Attila Dolhai and three virtuosos from Hungary, who received a standing ovation for their show.

Gyula: After we realized that the cooperative system wasn’t going to be easy to implement, we switched to building relations between the two countries via innovation, i.e. helping Hungarian innovators to create a market in America. Our plans didn’t materialize either, probably because of the difference in thinking between the Americans and Hungarians. I felt that the Hungarians were always afraid that their know-how and trade secrets, etc. would be stolen from them. I helped them to participate at various business events, but for some reason they didn’t manage to do business in America. Hungarian inventors aren’t familiar with the American way of thinking. In the American business world, which I know well, there is a strong reciprocity and thus generosity. Hungarian thinking is not so free.

Zsuzsa: They certainly lacked the security, and although we tried to bring them together and support them, unfortunately it wasn’t enough. We could have used more help from the Hungarian government, but the Ministry of Innovation also changed leaders so quickly that there was no stable background to support our plans. There was a young man, Gergely Papp, formerly a student at the Gábor Dénes School in Szeged, who got to America with our support, where he came third in a prestigious innovation competition. But after a while, when he said he didn’t need our help anymore, we let him go; we had lots of other engagements.

Let’s talk about those other engagements!

Zsuzsa: We also worked for several years on other project ideas. We kept in touch with the then Minister and former Ambassador László Szabó, because my big dream and desire was to build a Big Hungarian Village in America. Any Hungarian who wanted to present any kind of product or service could do so there—bustling with all kinds of Hungarian cultural and gastronomic, business and innovation programs every day of that week. We researched and assessed the ideals, and Gyula put together a business plan, showing that it would cost effectively $1.5M. We also had a plan to create an American village in Hungary, where Hungarian Americans would be happily welcomed by the old country. None of these plans materialized…

What else has happened in the past 15 years?

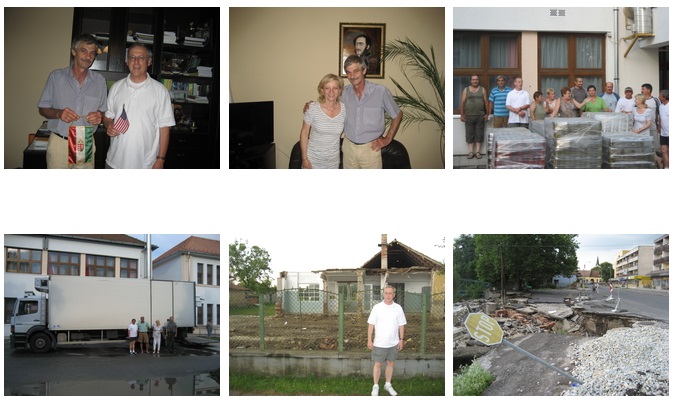

Zsuzsa: We have a lot to be proud of. The floods and disasters that happened in Hungary in 2010–2013 damaged many homes and farms, endangering the livelihoods of countless people. Americans for Hungarians Foundation, in partnership with AHF, collected charitable donations to rebuild the affected areas. Recognizing that the most effective use of donations requires projects with a lasting impact, we decided to modify the original plan to also help rebuild community centers and to focus our aid on farmers—which has had a multi-year impact, saving jobs in flood-affected areas. A Hungarian uncle in Florida donated $200,000, which we distributed. We did individual research to find out who needed what—it was a huge job.

Gyula. We also organized business, cultural and scientific programs in America as well as in Hungary. For several years, we organized a three-day program at the Kékessy Mansion in Tiszafüred, Hungary and we supported the Tisza Tavi Family Days in Abádszalók, where families and children from the surrounding villages come to celebrate together for a weekend. We visited the Hungarian English School in Mátészalka, after which we jointly established the Foundation for the Future of Our Children, which aims to support effective teaching methods in the American curriculum. We hosted Hungarian American students visiting Hungary as part of the New Brunswick–Debrecen Sister City Program. And together with Civil Forum organizers, we helped plant a thousand trees in a three-day event for Vizsoly, a town rich in historical references and often affected by the flooding of the nearby Hernád River. We also organized two charity Rajkó balls.

Gyula: We often visited Karcag for the Mihály Kováts Memorial Day, where we presented scholarships to three students of the Kováts Mihály High School. We also helped to introduce the Listen Drug Prevention Program, directed by Reverend Tamás Csapó from California, with whom we jointly applied to customize the program in Hungary, which has been implemented in several high schools in Óbuda, Budapest. And during the Covid pandemic, we distributed 700 hundred Hungarian Bibles in America through Hungarian organizations, providing spiritual comfort to Hungarian families living in the country.

Zsuzsa: We are also very proud to have produced a nearly 40-minute documentary in 2021, Hungarians Thank America, inspired by the feeling and way of life of dual citizenship, in which we wanted to showcase our patriotism to Hungary and our loyalty to America in a pioneering way. We’ve been careful to present Hungarian American organizations and their leaders, the most famous Hungarian American scientists, innovators, businessmen, artists, and athletes. One of the important goals of the movie is to raise awareness of what it means to be Hungarian in America, and to show not only the individuals, but also their achievements which contributed to the development of their host country.

What are your plans for the future?

Zsuzsa: The most important thing for us now is to find the treasure chest of our overseas Hungarian heritage and show it to the world, like the Peacock (Fölszállott a páva) or the Virtuosos talent shows in Hungary. There are huge Hungarian cultural and economic assets in America, too, that we still have no idea about. A talent contest would seek out overseas Hungarian (or of Hungarian origin) talents in the arts, music, innovators and science. Why not show off to the world our priceless overseas assets, which would enhance our home country’s prestigious reputation in a worthy way? Of course, we are aware that this plan can only be realized through a joint effort, as it would require a serious selection process, a mentoring system and management. We would also like to get help from Hungary to join forces. If the Hungarian government were to take it on board, we’d do it with all our strength and enthusiasm. It’s encouraging that Katalin Szili, for example, is supporting us.

Any other plans? Any thoughts about succession planning?

Gyula: We are going on holiday… (laughs)

Zsuzsa: We’re not giving it up, but we really deserve a holiday. Nevertheless, we’ll still be here to help where and how we can. We have no additional new goals, but we are happy to be partners in everything; nevertheless, we are no longer planning activities of the magnitude mentioned. We (would have) nominally handed over our volunteer work to others with a beautiful carved stick, but somehow it always turned out that it was up to us…

Gyula: In any organization in any country, the biggest question is how to move forward. Fortunately, the Hungarian Club in New Brunswick, New Jersey is now available to our youth, but it has also had very difficult times. The Hungarian scouts are also doing beautifully; they are perhaps the only organization that’s surviving worldwide; while at the others, where the founding leadership is aging, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find new leadership. Part of the problem is that older people find it difficult to hand over leadership. Another part is that young people think very differently from us. We have different histories, and thus quite different problems.

Zsuzsa: Gyula has always had the primary idea that it’s important to deal not only with organizations, but with the nearly one and a half million Hungarians (or those of Hungarian origin) in America. If there is just one Hungarian among us who enhances Hungary’s image and represents Hungarian values, we are happy to join forces, but at the moment we cannot estimate how many Hungarians are not members of any organizations—and therefore how much value is hidden in our Hungarian treasure chest. If someone doesn’t speak the language, but has Hungarian blood in his veins and in his soul, and he takes it on, then everything he has created, he did through his Hungarian roots. Companies where Hungarian labor, knowledge and innovation are to be found are also part of our invaluable shared values. Let’s open up our treasure chest! If we succeed, all our work will not have been in vain and our heart’s desire will be fulfilled.

Read more Diaspora interviews: