This is the English translation of the interview originally published in Hungarian on Magyar Nemzet.

Miklós Schlóder was born in 1935 in Bonyhádvarasd, Hungary, to a Swabian family. His life is like a historical record: his father was a soldier in the Second World War, took part in the invasion of Transylvania in 1940, and then fought at the River Don, from where he returned home on foot.

He was later drafted again and was taken prisoner by the Russians at the end of the war. His mother escaped from the Malenki Robot several times; the then 10-year-old boy witnessed multiple ‘visits’ by Russian soldiers on the run. Their fate was eviction and then deportation. His father and uncle, who had caught up with them in Germany, refused to go any further and waited there for the hoped-for Russian withdrawal, while the mother and her two children emigrated to America (New Jersey) after six years.

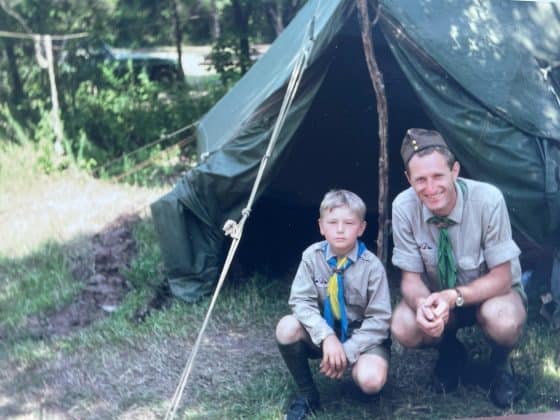

Thanks to his good drawing skills and technical acumen, Miklós managed to work as an engineer even with little education. Later he became the scoutmaster of one of New Brunswick’s most popular Hungarian scout patrols and led several Hungarian scout camps abroad. Meanwhile, he supported his mother in all things. Love and marriage found him at the age of 50, and since then, he has led a happy family life with his children from his wife’s first marriage, his grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

***

Listening to the events of your childhood is like reading a history book.

When I was three years old, my parents moved to the small town of Bonyhád because my father, József Schlóder, a master weaver, could not sell as much of his materials in the village as he could in town. Bonyhád was a farming town with 7–8 thousand inhabitants at the time; they bought a house there with a workshop, to which he added newly built extensions as well. When we got back parts of Transylvania in 1940, my father was called away to be a soldier. He came back home, but around ‘42 he was drafted again; he fought at the River Don. They were ill-equipped, and the army was absolutely unfit to fight. The Germans promised them all the supplies, but nothing came true. My father walked all the way from the River Don to Kyiv in that terrible cold winter. He recovered, but in the spring of ‘44, they took him away again.

Meanwhile, our weaving machines were down, but as we also had land rented out, we could live off of it. We also had a big garden; my parents wove small things that people needed, like breadcloths. My sister Erzsébet Helma was born on New Year’s Eve in 1941.

After being drafted again, our father did not come back for the third time

—as we later learned, he was taken prisoner by the Russians, and we knew nothing about him for a long time. Then in the autumn of ‘44, the Russians appeared near Bonyhád. My mother was afraid, so she locked up the house in Bonyhád and we ran away to my grandmother’s house in the locality of Kistabód. My uncle, my mother’s younger brother Ferenc, was also at home because the regiment he belonged to was stationed at Lake Balaton, but he was wounded and was taken to hospital in Pécs. When he recovered, the doctors kept him there to help carry the sick, injured soldiers, so when the Russians marched in, my uncle Ferenc was the only able-bodied man in the village.

Do you have any personal memories of when the Russians came?

As a nine-year-old child, I was very impressed when the first stray Russian ‘visitors’ appeared. I only heard some of the details later when people told my grandmother about what happened. Our great-grandmother was also still alive at the time. My mother would occasionally go to Bonyhád—but always on the back roads—to see how the house was holding up. On 1 January 1945, we woke up to a boy on horseback coming into the village, shouting that

the Russians had surrounded their neighbouring village and were taking the people away.

My mother jumped up, put on warm clothes, and wanted to run away, but my grandmother told her that she had heard that they were taking people to Vojvodina, to bring in corn. However, my mother said no, they were taking them to Russia; she had heard it in the German broadcasts back in Bonyhád. My mother called out to the neighbouring women as well and went off with them in the snow. She left us with our grandmother because she knew they would only be looking for people her age. My uncle was away at the time as he went to visit his other sister in Nagymányok. The husband of the sister of one of the neighbouring girls who was running away with my mother was a miller, so they ran to the mill, hid in a cave near it, and prayed. They stayed there in the cold January winter for ten days or so; it was the miller’s mother who brought them food.

Not long after my mother and my brother had fled, two Russian gunmen and an interpreter came. My grandmother and I were standing outside on the porch with my sister. First, they asked where our father was. My grandmother answered that she didn’t know; he was either in captivity or dead. Then they asked about my mother. Again, she said she didn’t know. They replied that they would come back tomorrow, and if the mother of the children would not be here, we all would be shot dead. My grandmother angrily replied that they could shoot her now anyway because she didn’t know where she was. The next day they came back and questioned her again, but then they gave up and finally left.

Shortly after, came the second collection of the Malenki Robot. A Hungarian policeman came to my mother from Bonyhád saying that my sister had to be enrolled in school in Bonyhád because she was a resident there. He took my mother with him, too. When they reached the outskirts of Bonyhád, a drummer was there and announced that all those whose family members had come to register for school in the morning should bring warm clothes and food for ten days. My mother said to the policeman, ‘You can shoot me if you want, but I’m not going there’. She turned around immediately and came home through the fields. The policeman had the decency not to shoot her.

In March, my grandmother and I were waiting on the porch when the Hungarian police came. My uncle was again in Nagymányok at the time, and my mother had gone to Bonyhád to see how the house and the workshop were. They wanted to take my grandmother away, but she told them that her mother-in-law was lying in bed dying, and she also had to take care of a small child, so she couldn’t leave. Eventually, they let her stay, but they took me and all the able-bodied people in the village to the mayor’s yard in Nagytabód. We were waiting in three separate groups when suddenly my uncle Ferenc appeared and, with a small barrel of wine, managed to arrange for everyone to be allowed to go home. I found out what we had missed afterwards: inhuman conditions, lack of basic sanitary conditions, dysentery epidemic, etc. There were immature thugs in the police force who treated people roughly—according to one horror story, they threw water and feathers on old ladies and made them dance. It was a mindless show of force. It was only by the summer of ‘45 that things began to settle down a bit.

What was the situation like with the schools at the time? What language was spoken at home?

We spoke both Swabian and Hungarian at home. I had no problem with Hungarian because we also went to kindergarten in Bonyhád, where we spoke Hungarian with the other children. We grew up bilingual. After the situation was more or less settled, we moved back to Bonyhád, but when the Russians left, they locked up the workshop and the house there, and we were chased out. Thus, we had to live out in Tabód again. I didn’t go to school, but I didn’t miss it, I had fun—I liked to hunt, I had a dog and used to catch rabbits with it. Yet, towards the end of ‘45, my mother enrolled me in secondary school, as I had completed four years of elementary school earlier. However, Tabód was six kilometres (four miles) from Bonyhád, so I used to ride my bicycle to go to school, but on the muddy hillside, it was only possible to push it. Therefore, my mother arranged with a family living in Bonyhád for me to stay with them; she brought them food, but I didn’t see much of it and didn’t learn either, so she finally took me away from there. She took me to an old lady she knew, where I finally started to learn. Aunt Brunner was like a mother to me for a few months. Later my mother found us a one-room flat in Bonyhád, opposite our old house. It was an unpleasant feeling to live there…

And a year later it was even more unpleasant…

We were approached by a man who used to regularly buy materials from us—he bought everything and paid in Deutsche Mark. He said that we were going to be deported to Germany, and the Deutsche Mark would be a good thing then. On 10 April ‘46, a letter did indeed arrive informing us that we were to be deported, but it did not say exactly where. It was a central decision; Szeklers from Bukovina were resettled in the area, but in the end, it was a local man who was placed in our old house in Bonyhád. A cart came for us on 1 June; we could only take a change of clothes and an eiderdown with us. The eiderdown was a very good idea. When they put us on the freight train, people were afraid that they were taking us to Russia, but on the way, they opened the door and shouted out to the workers in the fields. That’s how we knew we were going West.

In Austria, we spent three days at the border. Whoever brought food with them ate, and whoever didn’t, raided the potato field. We later learned that we had been standing for so long because the occupying military authorities were arguing about whether we could be deported or not. When they concluded that we could, because it’s the ‘Germans’, they let the train pass. In Germany, we were split up and taken to different villages. We were taken to a small village in Hessen, Völzberg, where we were given a small room. The Germans had to accept the ‘Hungarian Gypsies’—they were under the impression that only Gypsies lived in Hungary. We received some aid from the Germans; my mother did handicrafts, and I looked after cows. I remember I sang to them in Hungarian: I didn’t know any folk songs, but I sang the national anthem, military songs I knew by heart, and religious songs. When I started school, there was no paper, so we wrote on newspaper margins. Sometimes my mother would dictate in Hungarian so that I wouldn’t forget it; since we had to speak German, my knowledge of Hungarian was beginning to fade away. We left the village in the spring of ‘49, after three years; we briefly stayed in Munich, where we registered as refugees, so we lived there and later in Windischbergerdorf in so-called distribution camps. From January ‘50 we lived in the emigration camp in Dachau for more than two years, then in May ‘52 we were transported to Bremenhafen, from where we left on the 1st of June and arrived in America on the 10th.

Who else from your family was there? How did life in America begin?

In 1946, only three of us were deported to Germany: my mother, my sister, and me. My grandparents were only deported later, in ‘48, to a tiny village in the mountains of Thuringia. We knew nothing about my father for a long time. When we found out that he was in captivity, we could write him a letter of twenty-five words, which was transmitted to him by the Red Cross. When he was released from captivity, he followed us to Völzberg, but shortly afterwards he went to work elsewhere in Germany. For years afterwards, only the three of us lived together, while waiting to emigrate to America. My mother wanted to leave Germany at all costs, but my father did not want to go to America—he wanted to stay and eventually go back to Hungary ‘when the Russians leave’. At one point they divorced;

we stayed with our mother, and by the grace of God, we finally got to America.

Our sponsors were nuns of Hungarian descent. They guaranteed our support through the family that had gone out before us: the Takács family, who lived on Plum Street next to the church, in what was then the ‘Hungarian quarter’, had to take us in and help get our life started there. We stayed with them for about a month, then rented an apartment. I got a job the third day after we arrived: I helped load trucks at the tobacco warehouse near the church, and in the winter, I worked in a box factory. Meanwhile, my mother sewed, and my sister went to St Ladislaus School. We could only buy the most necessary furniture. Unfortunately, my mother soon became depressed and couldn’t work for a while, but after a year she started to recover. In April ’53, I read my first book in English, and I also found books in Hungarian in the library; that was the first time I read the Eclipse of the Crescent Moon by Géza Gárdonyi. Later I worked in the workshop of a machine factory. I was hired as a simple labourer, but after a month I was already doing skilled labour. Then, two years later, I was asked if I could do any drawings. I had previously enrolled in a correspondence course where I had to do drawings, which I was very good at, so I easily got into the office; later I did engineering work as well (control system and mechanics).

In the first half of the 1950s, the Hungarian scouting movement started in America. When did you join?

I became a Hungarian scout in 1950—we belonged to the Gábor Áron Patrol No. 28 in Munich, as a so-called ‘scattered patrol’, where members and leaders often changed, going all over the world. In ‘50 we had our first big camp in Gauting, Germany, which I could only attend for three days because I was working as a fitter apprentice at the time. Then, when we emigrated to America, I didn’t join immediately. When I was 21, in the summer of ‘56, I joined the National Guard as a soldier. That was when we bought our first house, and I also had my first car by then. The house was in bad shape, and I didn’t know how to fix it up, but it felt good to finally have our own place. In late October ‘56, I was fixing the ceiling in the bedroom when an acquaintance asked, ‘Did you hear the big news? The revolution has broken out in Hungary.’ I replied, ‘It’s going to be a massacre—they’re not well-equipped’.

I was in the army for six years; I was discharged in ‘62. By that time, I was already a member of the New Brunswick Scouts. In ‘64, the Hungarian Scout Association in Exteris (Külföldi Magyar Cserkészszövetség, KMCsSz) bought the Sík Sándor Scout Park in Fillmore (upstate New York)—that was when I finished the scout leadership training camp. In ‘65, there was a small patrol camp I attended, and then the Jubilee summer camp in ‘66 as well. In ‘67, I applied for the scout leadership training camp as a trainer, where I was asked to join the New Brunswick Patrol No 5 as a scoutmaster. I took it on a temporary basis—then it lasted 14 years. There were no scoutmasters at the time because the previous ones had become college students and were out of town. I was lucky to have a Hungarian family from Canada move here; they had two boys, and the older one was very good with little children. Tomi Teszár was my saviour: while he took care of the little ones, I did the same with the bigger ones. We learned a lot of practical skills together and often went on different excursions. We tried to make the camps more interesting by taking the scouts, for example, to the New York Catskills and Adirondacks Mountains. When Erzsi Teszár became the leader of the girls’ troop, we all worked well together and built a good team.

Some say that those were the best years in the life of the New Brunswick scouts, when you were scoutmaster. What was your secret?

I don’t know.

What I do know is that the most important thing is love.

You have to know how to love these mischievous little kids because they can feel it. They don’t say it, they don’t know it, they don’t think it, but they feel it. Back then, the children were very enthusiastic. Sometimes I organized trips where only the leaders could go. We had cooking competitions between the boys and girls, baked bacon, and went sledding in the beautiful moonlight. Things have changed a lot since then. Scouts, for example, now do many other things as well and, for the most part, don’t go to church anymore. They still go to Hungarian schools on weekends because their parents take them, but the church is out of their lives now. The parents grew up in the pre-communist era, and back then, they and the former scoutmasters would go to church every Sunday. I often said to the kids, ‘We’ll talk about it after Mass,’ or I deliberately organized football matches after the Mass. Thus, anyone who didn’t come missed it. The boys were always enthusiastic, they had a good time, and everyone wanted to be there.

Why did you go to church then and why do you still go to church every Sunday? Where does your faith come from?

When I was a child in Bonyhád, it was natural, I was never asked if I wanted to. There was a railing in front of the pews, where believers had to kneel to take communion. Boys were on one side, girls on the other, and we all had to behave properly. Our teacher was the organist, and he was always watching us. We had the litanies in May, and we would always go there earlier and have a headbutting match next to the church.

The preserving force of faith helped us through many things in life.

Many times, we had nothing else to cling to; in the absolute uncertainty, God was the only sure thing. There was a cross at the crossroads near my grandparents’ house. When they felt the need, my grandmother would go out there with the girls to pray. My mother prayed a lot later as well. In Germany, where we lived, there was no Catholic church, only Lutheran, but there was a Catholic priest who said mass once a month in a neighbouring village four kilometres (2.5 miles) away—we would always walk there to attend it.

You have always loved children and scouting, too. Why didn’t you want to be a scoutmaster?

Because I always had a lot of other things to do, and I couldn’t afford to live like most Americans of my age. Boy scouts became like family to me. If they had a problem at home, they came to me, and I was happy to give them advice. Once a boy came to me and said, ‘Uncle Miki, I want to talk to you. I can’t live with my father anymore. I’m moving out tomorrow.’ His father had an accident, he was on painkillers, and he was very difficult. I warned him, ‘Your mother and your three younger sisters need you. You have to hang in there.’ The next day he called: his father had died during the night. If I hadn’t given him that advice, I would have felt guilty that his father might have died because his son had left the family.

One of my best leaders was István Vajtay; his brother Tamás became the scout leader after me. Later I led the scout leadership training camp five times, and when I was asked to lead a camp in Venezuela and Brazil, I went there too. It was interesting to meet Hungarians there. Sometimes I missed a year or two, but there were times when I jumped in to help in the middle of a camp. In the meantime, there were several Jubilee camps as well, where I always led the younger age group of 11–13-year-olds. At the last one I attended in Toronto, there were 119 of us in the sub-camp, and only three of us were adults. My deputies were Imre Lendvai-Lintner, now KMCsSz president, and János Glázer from Montreal, Canada who wrote wonderful poems about the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Imre and I prepared the whole thing together, and at the end, he complained that he had to lead the whole camp alone. I was always working on something else, and I sent him everywhere instead of myself. Not by chance: that’s how I prepared him. In the next Jubilee camp, I only prepared the programmes, games, and competitions in recitation and storytelling. I also showed them some Hungarian folk games and made competitions out of them. I stopped active scouting in 1986.

What happened afterwards? How did you start a family?

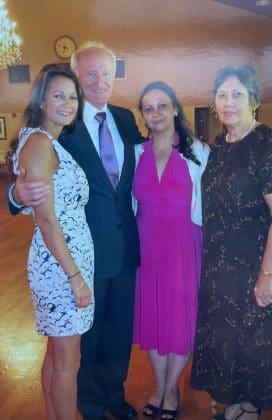

The Scout House in New Brunswick needed repairs. I got some dads together and fixed it up: replaced beams, repaired floors, replaced door locks. I was no longer involved with children at the time. In ‘87, the head of the Hungarian school asked me to teach history to the 13–15-year-olds until the new teacher, Eszter Tóth, arrived. The schoolmistress was smart and pretty, and although I was already 53 years old, I hadn’t thought about getting married before, as I didn’t even have time to court anyone. However, my mother and my sister were fine by then, so in ‘89, Eszter and I got married. In addition to her, I also ‘won’ a 19-year-old daughter, Éva, who was married in Hungary, and a 14-year-old son, Péter. In ‘91, our granddaughter Eszter was born, who later also came here with her mother, and Éva followed her mother in Hungarian education, too. Since then, we have already become great-grandparents, and our older great-grandchild is bilingual.

When I proposed to Eszter, I promised her that I would retire soon, and we would live in Hungary. We even bought a flat where our grandchildren would come to visit and spend the summer with us; but we’ve been here ever since, and we also sold the flat… My mother became ill, which settled the matter.

My whole life has always been guided by a sense of duty to my family.

Now we might as well go home, but we wouldn’t be any happier there. Relatives at home are now scattered all over the country, and we are not so mobile anymore either. Here we are part of our family and can help if needed. We live in a Hungarian community; we are happy here. If only we didn’t miss Hungary so much…

What happened to the relatives who stayed in Germany? Do you still see each other?

I visited my father several times in Germany. We kept in touch by phone and after the second sentence exchanged, we were usually talking about Hungary. He is buried in Bavaria. Since Ferenc’s fiancée stayed at home with her elderly parents, my uncle tried to run back for her twice, always without success. Still, he refused to come to America; like my father, he waited in Germany to return to Hungary as soon as the ‘Russians go home’. He finally stayed in Thuringia, started a family there, and is buried next to my grandmother in the Thuringian cemetery. We visited him in ‘94. His legs had been amputated because of diabetes, but even then he kept saying, ‘If I still had my two legs, I would already be at home in Tabód.’

How do you celebrate Christmas?

For me, early Christmas traditions continued in my own family circle, but Eszter didn’t practice religious faith regularly at home, and the communist regime did not support church attendance either, so her experience with the holidays was rather fragmented. Here, however, we have a real preparation period that is, or was, more typical only in the latter period of Advent’s time at home. Our Christmases are more peaceful and warmer despite all the frills and glitter. Our tuning in is more serious, we pray more, and we put our relationship with God first: Sunday by Sunday, we await the birth of the Saviour, strengthened by the Holy Mass. We have not adopted American customs, except that we put candles in the window during Advent and have an Advent wreath on our door, too, not only on the table, but we put up the Christmas tree only on 24 December.

Christmas is also celebrated in the Hungarian way: on Christmas Eve we eat fish, once with our children, but now they spend it with their own families, so we invite our lonesome neighbours over. Afterwards, we attend midnight mass at the Hungarian St Ladislaus Church in New Brunswick, and then Father Imre Juhász’s birthday celebration that lasts until dawn. On Christmas Day, we attend Mass again, followed by a family lunch and gift opening. We gather around the tree, remembering why we are together: to celebrate the birth of Christ. We sing Christmas carols and then eat cookies. It’s physically more and more demanding but spiritually uplifting, so we go as long as we can; even the distance, a half-hour drive, can’t stop us.

All the photos in this article are courtesy of the Schlóder family.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.