This is an abridged version of the original interview, first published in Kanadai/Amerikai Magyarság on 28 October 2023 and subsequently online on Bocskai Rádió on the same date.

Erika Papp Faber was six years old when her family fled from Budapest to Germany to escape the Russians, and five years later, they were able to emigrate to America. ‘It was a politically foolish idea to flee to Germany, but we survived, and I’m here to tell our story,’ she laughed. Her story includes 17 years of marriage, 14 years of editing an English-language missiological journal, 12 years of editing an online Hungarian cultural newspaper, a bilingual poetry anthology, and several religious-themed publications.

***

Tell us briefly about your parents.

My father, Remig A. Papp, was born in Budapest as the first child of Dr. Antal Papp and Hermin Négler. My paternal Hungarian Armenian grandfather was a financial director in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca, Transylvania, Romania) until the end of World War I; my father graduated from the Piarists there. My mother, Viola Vajk Papp, was born in Vajdahunyad (now Hunedoara, Transylvania, Romania), the youngest of six children of József Vajk and Piroska Malom. My maternal grandfather was of German origin; thus, my grandmother was the only one in the family of pure Hungarian descent. Both families had to leave Transylvania in 1919, and my parents met in Budapest.

From left: Etele Papp (my uncle from England), Milicza (twin), Álmos (youngest), Herta (twin), Milicza (other twin), Remig (my father) PHOTO: Family archive

My father graduated as an engineer in 1927. His first employer was the Berlin Siemens Bauunion—a construction company that still exists—and he worked there until the economic crisis broke out. In the meantime, he married my mother. My brother, Remy, nine years older than me, was born there. Afterward, my father worked in France for nine months, and in the early 30s they returned to Budapest, where he held a senior position at a dredging company. He designed the Northern Port and the ramp leading to the Margaret Bridge, which has since been replaced. He also designed our vacation home in Zebegény at the Danube Bend, where we spent two wonderful summers. In 1944, as the front lines got closer, my parents—based on their experiences from World War I—decided to flee to Germany as they knew some people in Berlin…Politically, it was a foolish idea; we hardly survived it, but ultimately, I’m here to tell our story…

In your memoir, titled With God’s Little Finger Over Us, you reveal that you believe your childhood prayers saved your lives in Germany…

Based on my childhood memories, I describe in detail in this book why we ultimately left Berlin, where my parents waited for a long time for the Americans to take over the city. I also explained how we survived Halberstadt’s strongest bombing attack, in which 80 per cent of the town and 2,500 people were lost, and 25,000 became homeless…Yes, I’m convinced that our survival was due to my prayers, as well as my mother’s recovery from severe pneumonia because God listens to little children. I also wrote about how my parents realized that the Russians, from whom we had fled over a thousand kilometers away from our home, were now once again on our heels…They panicked in Blankenburg, and we fled to Hannover, where we initially lived in a ‘refugee camp’ that consisted of summer cottages on the city’s outskirts. Since my father believed ‘whoever feeds me can dispose of me’, he moved us out of there as soon as he could. It was a wise decision because the camp was in the British Zone, and the British soon sent a number of refugees from the camps back behind the Iron Curtain. My father began working for the British, first in Minden; then the office moved to Essen, which was so far that he couldn’t come home even on weekends, so eventually, we also managed to move there. We lived in a single room until June 1949, when we were finally able to leave for the U.S.

What was it like experiencing all of this as a young child?

Well, my childhood was quite brief. My parents enrolled me in the St. Margit School in Budapest, but due to the war, the school year didn’t start until mid-October 1944. By then, bombs were already falling—often before the sirens signaled them—so my parents didn’t dare send me to school. For my feast day at the end of August, I received a primer, which I read in two days. In Germany, the school didn’t start until January 1946. Since I was almost eight, my father requested that I be put in second grade, even though I didn’t know any German. However, it didn’t really matter since we only attended school for an hour, one or two days a week—and just copied the multiplication table—because they couldn’t heat the building. I went to school from January to March, then I got pneumonia and ended up in a children’s hospital, where I caught measles and later a stomach virus. Meanwhile, my mother also got seriously sick and was sent to another hospital. My father ran from one hospital to the other, then returned home to take care of my brother, who caught the measles from me…But we survived that, too. After Easter, I found myself in third grade, without ever having attended first grade, and only a few weeks in second grade.

Who helped you to immigrate to America, i.e., who were your sponsors?

My mother’s brother, Dr. Raul Vajk, received a research scholarship to Houston, Texas, in the late 20s to work at a large oil company that later became Standard Oil. When his scholarship ended, he returned to Hungary, but he wrote a letter proposing to one of his coworkers. She followed him to Budapest, where they married and had three children. When the Russians arrived, my aunt and the children were able to return to America with their American passports, but my uncle wasn’t allowed to leave as a show trial against the Hungarian Standard Oil company was planned. However, the Russian commander’s girlfriend wanted an electric refrigerator. My aunt had ordered one from America in the 30s, and that became the price for my uncle’s departure to join his family in 1946, after a nine-month wait. From the U.S., they started sending life-saving packages to us in Germany. The used clothes were helpful, but even more so were the coffee beans. My mother would roast and pack them into small bags we made from newspapers. We’d go to the outskirts, and where we saw chickens in a garden, we’d knock on the door. Occasionally, doors were slammed in our faces.

When we moved to Essen, things got even worse. Essen had numerous coal mines, and because coal was needed to keep the country running, miners could get everything that was out of reach for common people—thus, we couldn’t do anything with the coffee beans. We were God’s poor. When my uncle sponsored us in 1949, we had to go through various medical exams and consular hearings to determine whether we were Nazis or Communists. In response to a question, my father said: ‘If I was a Communist, I’d have already been a state secretary at home…’ Thanks to the Berlin Blockade—during which the Western Allies developed a plan to land planes every thirty seconds to supply the 2 million Berliners with food and coal, ensuring the planes didn’t return empty—we were able to leave Europe by plane. We arrived at Idlewild, later renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK), on 11 July 1949. Since it was cool in Northern Germany, even during the summer, I wore a winter suit and a spring coat, and when we arrived, I thought I was going to die from the heat. The air was so humid I could only gasp, and it stayed that way all summer.

Did your parents find work easily? And how did you adjust?

My uncle had to guarantee agricultural work for my Dad and my brother; otherwise, we wouldn’t have been allowed in. My father and my brother went to a dairy, but the owner told them that even though he had guaranteed jobs for them, there had been such a drought that he had to lay off his own workers and couldn’t hire them. Eventually, they found janitor jobs at Princeton University. My father didn’t even know how to use a mop, but he cleaned for three months because he had to support the family. Afterward, he got a job as a draftsman in New York, which he commuted to for a year and a half, and then in 1951, we all moved to the city. Over the years, he worked his way up until he was an Associate in an engineering firm. We lived in Queens, where I could finally attend the same school for four years.

After school, I wanted to learn Arabic, but my father wouldn’t let me, so we agreed that I’d study foreign affairs at Georgetown University, originally a Catholic (Jesuit) school. A few years ago, I returned my school ring to them because not only is it forbidden to talk about religion anymore, but when a high-ranking politician visited them, they covered the religious symbols with flags so they wouldn’t offend anyone…The university practically denied its own mission!

How did you begin your career as a journalist?

They were looking for someone who spoke both German and French to edit a quarterly journal for an international Catholic mission-supporting organization founded by Bishop Fulton Sheen, the first televangelist in the United States. By the time I got there, he no longer worked there; the organization was run by his successor. I was the editor for almost 14 years, until the last director shut it down, claiming it wasn’t profitable, though it wasn’t founded to make money…We received submissions from all over the world, as well as publications in French and German, but I also translated from Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese, which I learned in night school. I wouldn’t say I can speak these languages, but I could understand the text, and there’s always a dictionary…Sometimes, I’ve come across Hungarians in the most unlikely places. For example, I saw an article by a certain Rev. Laszlo LaDany from Hong Kong, who translated from Chinese to English. When I contacted him, it turned out that he had a niece in England whom my uncle and his wife were supporting.

Did the journal influence your personal faith?

I’m Catholic. Not always a model Catholic, but I’ve never turned my back on God. Yes, the job meant a lot to me, and it strengthened my faith. For example, due to my work, I got close to Cardinal Mindszenty, and because of him, I started attending Mass at St. Stephen’s Church in New York, where I met my husband…Cardinal Mindszenty first came to the U.S. in 1973 to consecrate the newly renovated St. Ladislaus Church in New Brunswick, New Jersey. A news agency hired me as a reporter because I spoke Hungarian. I saw him arriving at the airport, and I also reported from the church. Unfortunately, my name was often left off my articles…The next year, when he visited us again, I was again present as a reporter at every location he visited around New York. He always talked about supporting Hungarian churches—that really stuck with me.

The only Hungarian church in New York was St. Stephen’s, located in Manhattan, whereas I lived in Queens at the time in my own apartment. The journey took an hour and a half with two long subway rides and a very long walk, while my local parish was only five minutes away on foot…Our family never lived in Yorkville, the ‘Hungarian Quarter’, and due to the big distance, we couldn’t fully integrate into the Hungarian community. We didn’t have a car—my father didn’t like cars—so we only went into the City for Hungarian events. However, due to Mindszenty’s visits, I came to the conclusion that I must also make some small sacrifices. When I first attended the Mass, people remarked that they were happy to see me and asked why I didn’t come more often. A kind man offered to pick me up by car on Sundays. He even gave me his phone number, and surprisingly enough, he kept his word. We had great conversations on our way. That was in July 1974, and the following May, we got married. I was already 37 at the time, and Oszkár Faber was 22 years older than I was, but we had many shared interests. Tibor Mészáros, Mindszenty’s secretary, whom I had previously interviewed, sent the Cardinal’s blessing for our wedding. It was probably his last signature because he passed away the next day…

Tell us more about your husband and your marriage.

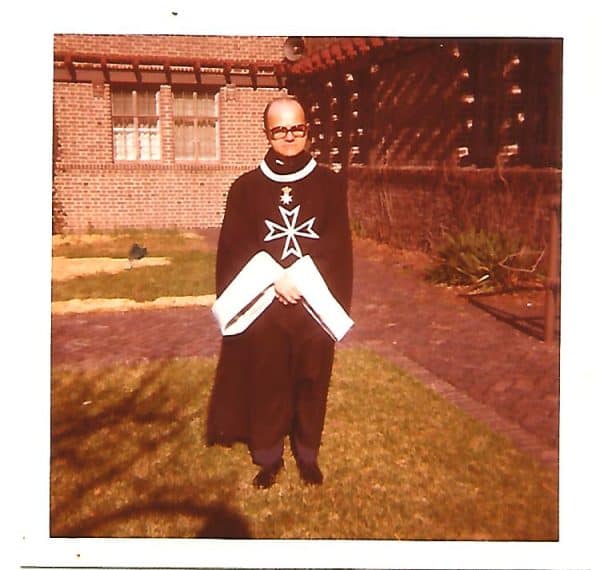

Oszkár was an athlete at the Hungarian Athletic Club (Magyar Atlétikai Club, MAC) in Budapest, a successful long jumper and sprinter, competing under the name Fábri. If he hadn’t had an accident, he’d have been part of the 1936 Olympic delegation; moreover, he likely would have won, as he had set a long jump record that remained unbroken for 14 years. He earned a doctorate in law and worked at the Ministry of Transport. He was responsible for distributing fuel during the war, prioritizing drivers over the wealthy, which led to conflicts. He was a very kind-hearted man. In New York, he worked for Pan Am Airlines for 30 years before retiring. He was very active in the St. Stephen’s Church community: he created the first bulletin and was a founding member of the St. Imre Club. He also involved me in many of his activities.

We had no children, not only because of the age difference but also due to Oszkár’s illness. I don’t know exactly when it started; I just felt that our marriage was slowly falling apart…We constantly argued about who had said what. He often came home late and angry from work, and only later did I realize that he had probably gotten lost. But when he could no longer finish his sentences, I took him to a neurologist. The doctor diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease, but I couldn’t accept that nothing could be done. So, I kept taking him from doctor to doctor until I found a Hungarian neurologist and naturopath who told me: ‘Not everything that looks like Alzheimer’s is actually Alzheimer’s.’ He promised to rule out everything he could. We managed to extend his life by eight years, but it was a very difficult period, both financially and emotionally, as my job came to an end just when he retired. Fortunately, I had a small inheritance: my uncle and aunt in England left me their small house, which was almost enough for us to move to Connecticut, near my brother, my only relative. His wife had multiple sclerosis, so we couldn’t help each other much, but at least we met during the holidays. Oszkár passed away in 1992 after 17 years of marriage.

Is that when you started writing? Why in English?

I started writing the memoir because I finally had time for it. I first wrote about my childhood memories in Germany, followed by excerpts from my father’s diary and my parents’ family correspondence, which I translated, and then I wrote a summary of our family life in America. I wrote in English because that was the only way Americans could read and somewhat understand the horrors of war, and especially the post-war period, which they had never experienced. I see myself as a bridge.

Even when I was young, I was interested in how we could introduce Hungarian culture to others. When I was in high school, no news came from Hungary, so I came up with the idea of creating a card catalog system as a central place for leaked news from Hungary. In the spring of 1956, Father Csaba Kilián, a Franciscan priest, spoke on the New York Hungarian radio about the approaching 500th anniversary of the Battle of Nándorfehérvár. Inspired by this, I wrote my last high school essay on that topic. That was the beginning…

Your Hungarian seems perfect. How did you manage to maintain it with such a diverse family background and an adventurous life? And what about your translation skills?

The unparalleled beauty of Hungarian poetry is barely known outside the Hungarian-speaking world. The main reason is the complexity of our language and the rarity of faithful translations. It’s not enough to know two languages; a good poetry translator must be deeply immersed in both cultures. Only then can the translation remain faithful to the original. I follow Kosztolányi’s principles—he believed in absolute fidelity to the source text. The 20th century ensured that I felt at home in two cultures. I inherited a bit of poetic sensitivity, too, which helped me compile A Sampler of Hungarian Poetry, a bilingual anthology that won multiple awards: a Gold Medal from the Árpád Academy in Cleveland in 2004 and the Hungarian Gold Cross of Merit for translation and literary translation in 2020.

At home, we always spoke Hungarian, and although I never attended a Hungarian school, I learned Hungarian poems and even wrote both Hungarian and English poetry. My father organized a literary lecture series at the university, introducing the poetry of Áprily Lajos to Budapest audiences. My mother knew many poems by heart and recited them to us. During our difficult times in Germany, my parents compiled a Tiny Hungarian Anthology from memory for their own and our enjoyment. My first poem was a homework assignment in Germany; my parents sent it to my grandfather in Budapest, who sent back a translation. That was my first encounter with poetry translation. Years later, in America, I began translating Hungarian poems into English, inspired by finding an anthology with French translations in a little hidden bookstore in New York. I thought to myself that we also have poems just as beautiful as the French ones. Another great encouragement came when my uncle asked me to translate one of the poems of Loránd Eötvös for a biographical presentation.

You also edited an online Hungarian newspaper for many years. How did it start?

There used to be a Hungarian radio broadcast in Bridgeport, Connecticut, which unexpectedly ceased in 2007. At the time, journalist Jóska Balogh said: ‘There must be a Hungarian press’, so he started an English-language monthly paper, the Magyar News. At first, it was only four pages long, but later, it expanded to ten or 12 pages and was mailed to 34 states. I regularly wrote articles for it. When Jóska’s only son suddenly passed away, he said he could no longer continue. So, in 2007 a few of us joined forces and launched Magyar News Online, a cultural online magazine. Bob Kranyik, the dean of Bridgeport University—who, despite being a third-generation Hungarian, still valued his Hungarian heritage—became the first editor.

We had a great team: Olga Vállay-Szokolay, an architect; Karolina Szabó, a computer systems organizer who worked for the Bridgeport Newspaper; Éva Wajda; Paul Soós, who was born here, just like Charlie Bálintitt Jr.; and Judit Paolini, who left Hungary as an eight-year-old in 1956 and barely spoke Hungarian any more but was very active in local Hungarian organizations. We also had Zsuzsa Lengyel, the head of Hungarian Studies of America, under whose aegis we operated. We didn’t engage in politics, but we covered everything else that was Hungarian: history, tourist perspectives on Hungarian towns, traditions, folk songs, etc. We learned a lot from it ourselves: whenever a topic came up, we researched and studied it thoroughly. I didn’t want to take on the editorial role, but a year and a half later, it fell to me. The newspaper replaced my family in a way. We gathered every month to celebrate birthdays, for example. We only raised funds two or three times—because we had to pay for hosting the content online—but otherwise, everyone was a volunteer. Honestly, it wouldn’t have been possible to compensate us for our efforts…

Why and when did it end?

In May 2021, because we simply couldn’t keep up anymore. In October 2020 I had a terrible surgery due to an unexpected bowel obstruction. I spent three weeks in rehabilitation, but two days after coming home, we had to upload the next issue. I was completely exhausted from the constant rush, and so were the others—we weren’t getting any younger. After the last issue was published, at the 4 June commemoration for the 110th anniversary of Joseph Pulitzer’s passing, the Hungarian Consulate in New York unexpectedly honored us with an award. We had no ‘trained’ successors, though several people expressed interest in carrying it on. But we didn’t want to because we couldn’t guarantee the quality, nor did we know how they intended to use it. This work required an immense amount of effort, intellectual investment, dedication, and instinct…Today, the only printed Hungarian newspaper in North America is the Kanadai/Amerikai Magyarság, which should be supported so it won’t disappear.

***

After completing the interview, I received a poem from Erika, which I’d like to share with my readers.

A Song of Praise

O praise and bless

the Lord, my God.

He has lifted my burden

wiped away my tears.

O praise and bless

the Lord, my God,

He has set me free

from the bondage of fear.

O praise Him,

praise Him forever!

O bless and praise

my God! My God!

(Connecticut, 23 December 2023)

Read more Diaspora interviews: