As a German language teacher and linguist, Gergely Tóth went to the University of Berkeley, California 26 years ago for a doctoral program, where he soon became immersed in local Hungarian community life. Since then, his voluntary work extended from making oral history interviews to photographing objects and markers on four continents, and collecting archival material of the Hungarian diaspora. The results are preserved on his website and in his home. Later, he plans to place this digital and archival wealth on the ‘table of the nation’.

***

How did you come to America?

I was born in Budapest in 1970; graduated in German there in 1997, and in 1998 I started my doctorate in sociolinguistics at the University of Berkeley, California, under the leadership of Professor Irmengard Rauch. There I taught German as a lecturer for seven years. Berkeley also offers Hungarian courses, and when the previous instructor became ill in 2007, she asked me to take over her Hungarian language classes. I lived in California until 2012, then moved to Utah to be close to my sister’s family and spend more time with my two nephews. I taught German at the University of Utah. In 2017, my sister’s family moved back to Hungary. At that point, I didn’t want to return to California, so I moved to Florida. It’s not really my world, but I knew the place from previous trips. When I arrived, I didn’t have a job or a place to stay, other than teaching one Hungarian online class for adults, which was a project Dr. Endre Szentkirályi asked me to take over at Cleveland State University in 2015. In January 2019 I got a job at Florida Atlantic University where I’ve been teaching German, currently online. In early 2006 I enrolled in a bartending course out of curiosity. Since then, I’ve been working also in bars, lately in Florida during the main tourist season, because teaching isn’t paid well in the U.S. either. But overall, I’ve been in the process of moving back to Hungary.

Your collecting activities seem to be more than just a hobby. How did it start?

It’s indeed much more than a hobby: it’s a passion. I’m fascinated by the ‘detective’ work involved, the joy of discovery and meeting people. This is how you really get to know a country, not necessarily through tourist attractions. Those are also important, but an old industrial town in the Rust Belt around Pittsburgh, or a mining hamlet in Virginia are places that the average tourist would never go to. That’s one of the things that excites me.

I first encountered Hungarian communities in California. My uncle had mentioned that one of his former schoolmates lived in the San Francisco area, who gave me a list of Hungarian organizations in the Bay Area. I picked the name András Rékay, president of the San Francisco chapter of the Freedom Fighters Federation, who came to America as a child following the 1956 revolution. He and his wife, Cecília, invited me to their home in Oakland. Thanks to their stories, the Hungarian world in North America opened up to me. One connection came after another, and it occurred to me that I should do interviews. András’ sister was visiting from New York, so I started the series with her. It was quite an intense project for 15 years, but in recent years I’ve gradually wound it down. I conducted about 250 oral history interviews with 1945ers and 1956ers, as well as some so-called ‘Old Americans/Argentinians/Canadians’ at the last minute before they passed away.

Before we go any further, please share some information with us about your interviewees.

Just to mention a few: in California, one of the best-known Hungarians was actress Éva Szörényi, 1956er and former member of the Hungarian National Theatre. Among clergymen, I would mention the Reformed Bishops Sándor Szabó in Ontario, CA and Kálmán Ludwig of Hammond, IN, as well as Fr. Maurusz Németh of the Hungarian Catholic Mission of San Francisco, or Fr. Alfonz Skerl in East Chicago, IN. My subjects from South America were very interesting too. There, I interviewed old members of the Royal Hungarian Military, church and association workers, two ‘Old Argentinians’, as well as Hungarian journalists such as Zsuzsanna Kesserű Hajnal who ran the Hungarian monthly in Argentina. In Australia, I would definitely mention the legendary journalist Endre Csapó. In New Zealand, I met Klára Szentirmay, whose father was the first honorary Hungarian consul there. In Paris, I spoke to Jenő Sujánszky, a freedom fighter in 1956, who spent a long time in communist jail and organized the annual 1956 commemorations at the Arc de Triomphe until his death. Another memorable encounter from Europe was the Benedictine Father Iréneusz Galambos, former headmaster of the famed Hungarian refugee high school in Burg Kastl, Bavaria, also a 1956er, whom I spoke to in Unterwart, Burgenland, where he served the Hungarians at the end of his life.

Two of my favorites were the incredible Éva Saáry from Lugano, and Mihály Ugri from Graz. I managed to catch a couple of ‘Old Americans’ at the Bethlen Home in Ligonier, PA, around 2002, as well as some others in California, East Chicago, and South Bend. They still spoke a dialect that no longer exists in Hungary, but their parents passed this onto them at the beginning of the 20th century, so listening to them was a special experience. There are many others to recall, such as Dr. Gyula Nádas, president of the Hungarian Association in Cleveland, the tireless Katalin Vörös (Berkeley, CA, now Cleveland, OH), the Kerkays in Passaic, or Dr. István Déness in California, one of the last living survivors of Recsk, ‘the Hungarian Gulag’ communist camps. I recorded two ‘Old Canadians’, Mr. and Mrs. Daku in Békevár, Saskatchewan. Most recently I interviewed the wood carver György Müller, a former teacher at Burg Kastl.

I only look for people who have done some, potentially significant volunteer work for their Hungarian community. Just because someone is Hungarian, even if they have an interesting escape story or later professional success, but never volunteer or attend a Hungarian event, that in itself doesn’t make me interested. About 80 per cent of my interviewees are no longer alive. Contacting heirs or consulting lawyers hasn’t been a priority, so the recordings are not public yet. I also recorded hundreds of Hungarian diaspora events prior to 2015—church services, festive programs, Hungarian Congresses. A list of these (and about 60 of my photographs) will be included in the second edition of Béla Nóvé’s handbook on Hungarian exile and diaspora, under the auspices of the National Széchényi Library. He already dedicated a separate section to my work in his first edition.

Tell me more about the other layers of your work.

In San Francisco, I got involved in the life and work of local Hungarian organizations such as the Catholic Mission. I also went to the Reformed Church, because there was quite a vivid life—not just congregational but also cultural—during the time of Rev. Jenő Katona, originally from the Partium in Romania. I became secretary and a member of the Festival organizing committee of the Hungarian Heritage Foundation of San Francisco. I joined the local chapter of the Freedom Fighters Association as a supporting member. Then I started to write articles for Hungarian newspapers in the diaspora. I’m a member of the Árpád Academy of the Hungarian Association of Cleveland, where I received their Gold Medal in 2010. Between 2010 and 2012 I was technical editor of the American Hungarian Educators Association (AHEA), and I’m also contributing as a U.S. correspondent for the Hungarian Radio Hour of Sydney.

You became editor of Hadak Útján, and later head of the World Federation of Hungarian Veterans (MHBK), its publisher. Why?

MHBK is one of the oldest Hungarian diaspora organizations, founded in 1947 in Austria, to bring together the scattered members of the former Royal Hungarian Army who couldn’t return to Hungary due to Communist persecution. It’s still active on four continents, but limited to the preservation of traditions and the publication of the journal. In 2011 I happened to interview Károly Borbás in Toronto, the editor, who handed over his role to me in January 2013, well after his 90th birthday. The newspaper was launched in 1949 and is the third oldest Hungarian press product outside the Carpathian Basin. Our content is divided into two sections: first, news of our member groups such as Adelaide (SA), Chicago, Calgary, Buffalo, Toronto, or São Paulo. The second half is reserved for associations in Hungary that are involved in preserving military traditions. I also put emphasis on finding the last living witnesses of the WWII era and including their original and current accounts. By the way, I’ve managed on two occasions to connect WWII veterans who had not met or known about each other for 50–70 years. The image of two old comrades reuniting, one from Buenos Aires, the other from Los Angeles, stuck with me. These are unique, heart-warming occasions…

Later, in 2021, László Simonyi, MHBK’s leader based in Chicago, asked me to take over his position. He is also over 90 now but still very active. I often ask him to write our lead article. I’ve been carrying out this double duty, keeping a promise I made to these men. In 2023 we placed a memorial plaque for MHBK in Hungary, the first in the country. It was unveiled at the Ludovika Academy in Budapest, the flagship institution of Hungarian military officer training until 1944.

How do you take your photos?

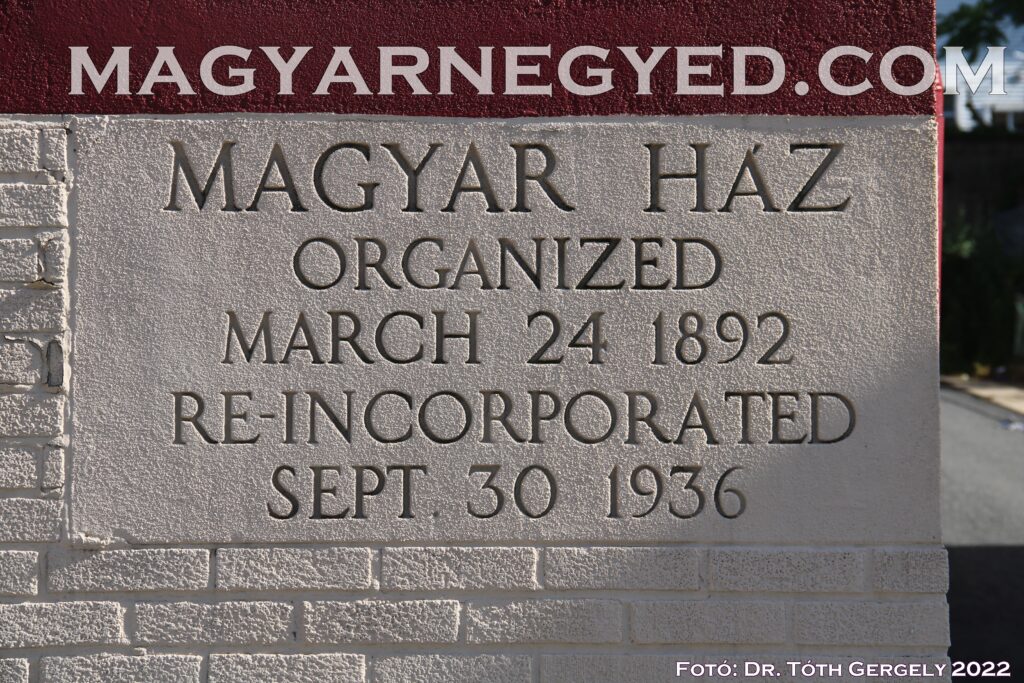

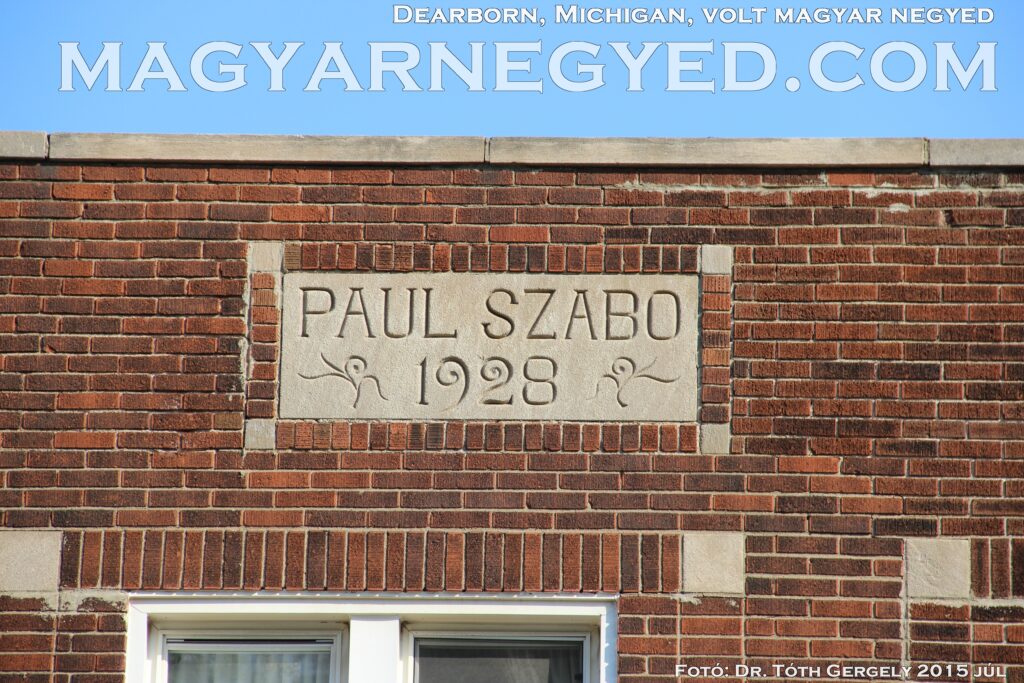

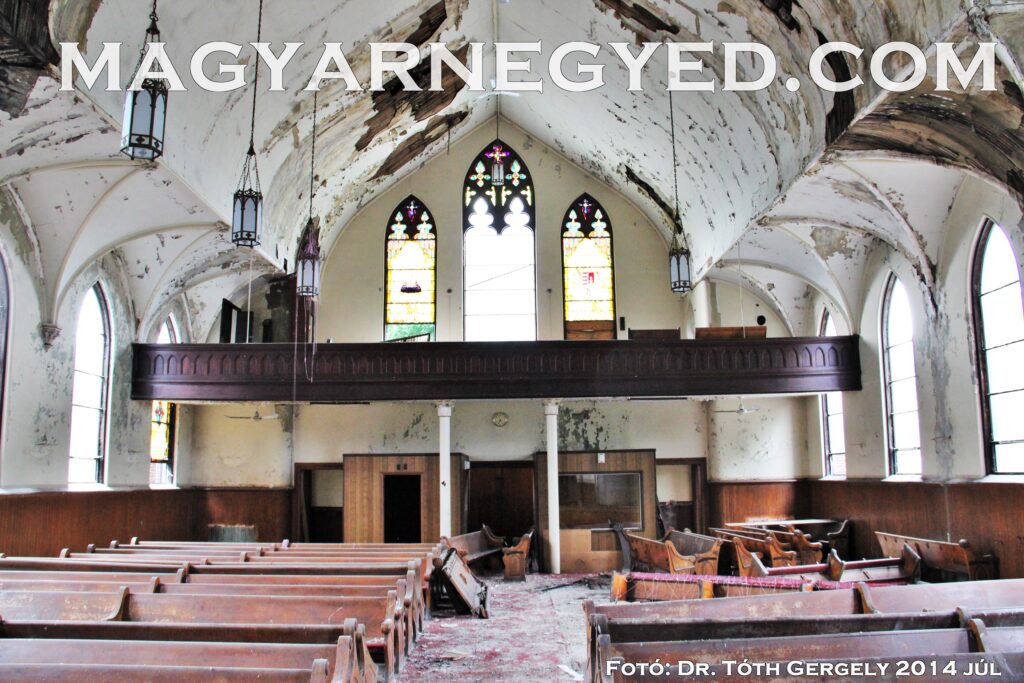

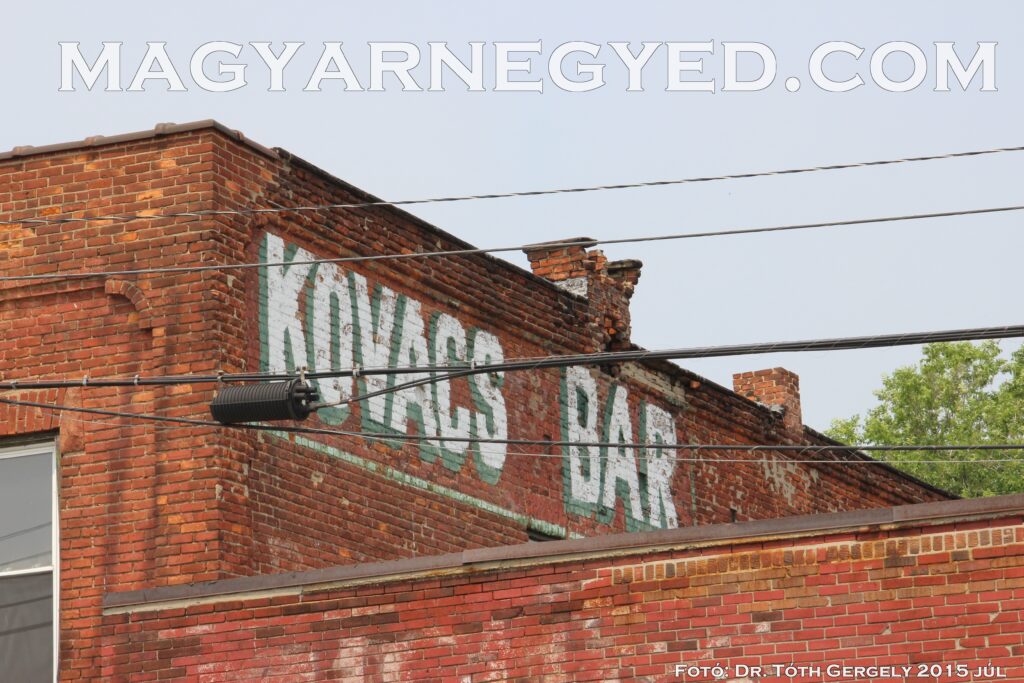

I’ve been focusing on markers and objects of the Hungarian diaspora since 2007: buildings of current and former Hungarian churches, Hungarian Clubs and Associations, memorial plaques, historical markers, street signs, Hungarian statues, 1956 monuments, Cardinal Mindszenty memorials, Hungarian shops, restaurants, as well as meeting places, even if they are or were not Hungarian-owned or operated, but where Hungarians met regularly for various functions. Around 2017 I added cemeteries too. On top of that, I spend almost equal time, on site or during the year, photographing printed material pertaining to the objects or buildings I visit—newspaper clips, ads, church bulletins, historical photographs, program flyers, record books… My aim is to fill these places, many of them abandoned, with some life, names and stories, and this way reconstruct the history of these locations or the surrounding Hungarian community—as much as this is possible for an outsider in 2024. In my picture series, I present the sites in a tour-like way; as a student, I worked as a tour guide. For example, when photographing a street sign, I capture the whole street scene, so that the viewer can see the surroundings, and better imagine the person’s story the street was named after. A section of the Miami freeway is named after the Hungarian American Don Shula, a successful American football player. I walked out to the road shoulder and photographed from a couple of angles. A different-scale example is Nelsonville, Ohio where I found a Toth Drive, a small, 15-yard dirt driveway, ending in some plastic buckets.

What were your most memorable photo shoots?

Since many former Hungarian buildings are gone by now, I make sure to take photos of the wider area, the old Hungarian neighborhood, to show what the streets look like today in the area where Hungarians used to own most of the houses. A great experience, a bonus, is to find someone of Hungarian origin. For example, I accidentally met a lady, an Almáshy descendant, next to the former Hungarian church in the forgotten coal mining hamlet Congo, OH, who brought out some family photos and even wrote a letter about who was who in the pictures. Another recent Ohio story: since I worked all summer organizing the Bethlen Home Archives and Museum in Ligonier, PA, I was able to spend the weekends visiting the greater surroundings. About an hour from Pittsburgh there is an unincorporated area called Crescent, another former mining place. In old sources, I came across the local Hungarian Presbyterian Church that ceased to operate in 1996. Their two small bells are on display in the park of the Home in Ligonier. I went to Crescent to find out if the cute little white wooden building was still there. It’s gone but there is a plaque in the grass where it once stood. I asked the neighbor who turned out to be Hungarian by background whether the last chief elder, Mr. Robert Bassa was still alive. She got very excited and told me that he was in fact her cousin and lived just under the hill. Robert and his wife were very kind, showed me old photos, articles about the church, and a Bible with their family history, all of which I also photographed. He guided me to the cemetery where Hungarian families are buried. They were touched by my visit, appreciated the interest, reminisced about old times, and I was able to put my story together.

You also have a substantial archival document collection. How did it start?

The collection started back in California with the weekly newsletters of the Hungarian Catholic Mission, then continued with flyers about various community events as well as diaspora newspapers. Most of these are at my place in Budapest. I’m sorting these out right now, so I have huge piles of newspapers and other written and printed stuff, program booklets, church bulletins, anniversary editions, old tickets, meeting minutes, old photographs. Much of this was given to me by elderly Hungarians on my trips. Their children and grandchildren no longer speak the language, these documents don’t have much value in their eyes, so sooner or later they would throw them away. For example, in Buenos Aires someone gave me a box of papers to save. Inside I found about ten postcards personally written by Cardinal Mindszenty. I also received old material on life in post-WWII refugee camps in Bavaria and Austria, among them a dossier from Buffalo and another from New York City, including information on the inhabitant refugees. This kind of data is very hard to find, and I’m particularly interested in that period anyway. I’ve visited almost all the former refugee schools in Austria and Germany. I would like to finish processing all the printed matter next fall when I’m back here in Hungary.

How much time can you dedicate to this project? Where and how have you travelled?

About four to six weeks a year. For this project, besides the U.S., I’ve been to Canada, Argentina and Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of Western Europe. With very few exceptions, 95 per cent of this work is self-funded. At the same time, I’m very grateful for any help on my travels, most often accommodation, local guidance, lunch packets, or simply tips on where else to go and what to look for. It’s practically a one-man undertaking. When I set out on longer stretches, I normally spend the whole day without even stopping for lunch. I often sleep in a tent or in a highway parking lot, and take no days off. Last year, when I was able to spend about 7–8 weeks on the road, I drove 18,400 miles.

I’m the only one in the world who photographs this particular topic at a global scale, in such depth, detail, and quality. I’m not so much interested in the architecture or the artistic-aesthetic value of a building but specifically any and all Hungarian aspects and references, from the basement to the attic. It’s not enough to have one photo of the façade and the altar of a church, I want to record as many details as possible. In Youngstown, the recently closed St. Stephen Church had 70–80 pews all labelled with donors’ names—a great documentary value. About halfway through, my camera starts needing extra time, as the flash overheats…

The reason for your incredible pace is obviously the passing of time…

This job is clearly a race against time. I’m limited by the schedule of my regular work, finances, and now by spending close to half of the year in Budapest. I have to plan ahead and squeeze as much into the available weeks as I can. There were lots of places I arrived at the last minute; just months or weeks later, the building was demolished, and who knows what happened to all the interior decoration. I also go to places that had closed decades before but the building is still there. These are often great moments of cornerstone discovery; sometimes I have to use clippers to cut through branches to get to them. Overall, I visit everything I know of if there is a story to tell and if there is anything left to document, even if it’s just a plaque in the grass or a single memorial marker.

Tell us about locations you got to at the last minute, or arrived too late.

In Cleveland there was Buckeye Road, the famous Hungarian neighborhood; Detroit had its own Hungarian section called Delray; in New York there was 2nd Avenue in Yorkville; Bloor and Spadina in Toronto; and Vila Anastácio in Sao Paulo. But there are also many lesser-known Hungarian places and buildings that are slowly or quickly disappearing. For example, in 2011 I stopped in Yonkers, NY at St. Margaret Catholic Church, which was already boarded up. I climbed over the fence, took pictures of the building and found a picture tableau about Cardinal Mindszenty by the wall in the back. However, I kept postponing going back for interior photos. When I finally got there in 2023, I saw the demolishing equipment and the containers in the yard and the church building had already been taken down.

When I interviewed Franciscan Father Domonkos Csorba in 2005 in the Hungarian parish St. Stephen in New York, I took some pictures inside, but only randomly. Around 2015 the Hungarian community unfortunately lost the church, it was annexed by an American parish and used partly as a school. I tried to get access to the building in 2021 and again this year, but the parish priest refused to let me in. The beautiful stained-glass window behind the altar is left in place, but everything else has been removed, including the Mindszenty memorial plaque from the foyer. The church will no longer be a place for mass. The structure has at least been preserved, but I won’t be able to take any more pictures of the original interior…

Your photos are posted on your website. In what other ways do you plan to use all your experience and knowledge?

Making a website has been a bumpy road. By late 2022 I finally managed to have a hopefully final version of my site, thanks to the financial support of the 1956er Tamás Jackovics of Oakland, CA. I currently have about 20,000 photos up but another 80–90,000 are still to be uploaded. It’s a bilingual image gallery site, organized by geographic regions. In addition, I’ve compiled a long list of addresses, including contact persons, practical details, as well as a brief history entry of most locations. Over the years I discovered some of the photos from my first website used elsewhere. I’ve become smarter since; downloads are now blocked. The picture purchase function isn’t yet working, but soon.

I also give slide-show presentations, on an invitational basis. In the long term, my aim is to put this vast material ‘on the Hungarian table’, but only in an adequate, secured format, not just letting it lie around in some drawer. I also plan to publish pictures in a book format, as it is still more durable and stable than websites. That’s why I’m glad I’ve contributed 100 of my photos (free of charge) to a jubilee album on the 100th anniversary of the Hungarian Reformed Church in America, at the request of Bishop Lizik. I’d like to publish more such albums, but for now, collecting and preservation are still my most urgent and important task. On the long run, based on solid agreements and in a thematically organized way, I’d be happy to deposit my photographic material with the appropriate organizations, for example the archives of the various denominations in Hungary.

Why did you decide to move back to Hungary? Any further plans?

I owe a whole lot to my years abroad, and I have great respect for most American values, but it’s time to settle down. Everything I was missing over there I can only find in Hungary. But I’ll always stay connected to the U.S. I made the decision five or six years ago, and in 2021 I started the moving-back process. By now, all my essentials are here, and all that’s left in Florida is what I need for everyday life and work. To be sure, it will still be easier to set out for the remaining North American stages of my photography from there: Chicago–Iowa–Wisconsin; the rest of New Jersey and Upstate New York; the rest of Pennsylvania; West Virginia–Kentucky; and more of Ohio and Michigan. Next summer I’ll be heading to Eastern Canada. When I’m done with North America, I’ll revisit South America and Australia, go to South Africa, and there’s still a lot left in Western Europe. So there’s still a lot of work to do in terms of photography, but I can see the end of the tunnel…

You mostly mentioned the positive side of your work. How much does your work affect you emotionally? You see plenty of signs of passing and decay…

I tend to be rational, as everything has a life cycle. Just today I photographed the 1938 Calendar of the Catholic Hungarians Sunday, listing the Hungarian Catholic parishes in the U.S. that year. There were at least 60 then; today there are only three, actually closer to two-and-a-half: Detroit, MI, Cleveland, OH and Passaic, NJ. I often think about this when I walk through old Hungarian neighborhoods, many of which have turned into depressing ghettoes. The streets used to be full of lively Hungarian homes and buildings and what’s left are often just empty lots or half-burned buildings, the original residents are in the cemeteries, and their descendants are scattered nationwide. At the same time, it also feels special to be walking on ‘Hungarian soil’… It’s an interesting mixture of feelings.

Read more Diaspora interviews: