On July 4, 2023, the movie Sound of Freedom, the now world-famous child trafficking drama was screened for the first time. This year’s Independence Day will see the debut of the same Angel Studio’s Sound of Hope, another thrilling movie about saving children’s lives, this time through ‘mass’ adoption. I had the privilege of watching Sound of Hope: The Story of Possum Trot, inspired by real events, before the premiere screening.

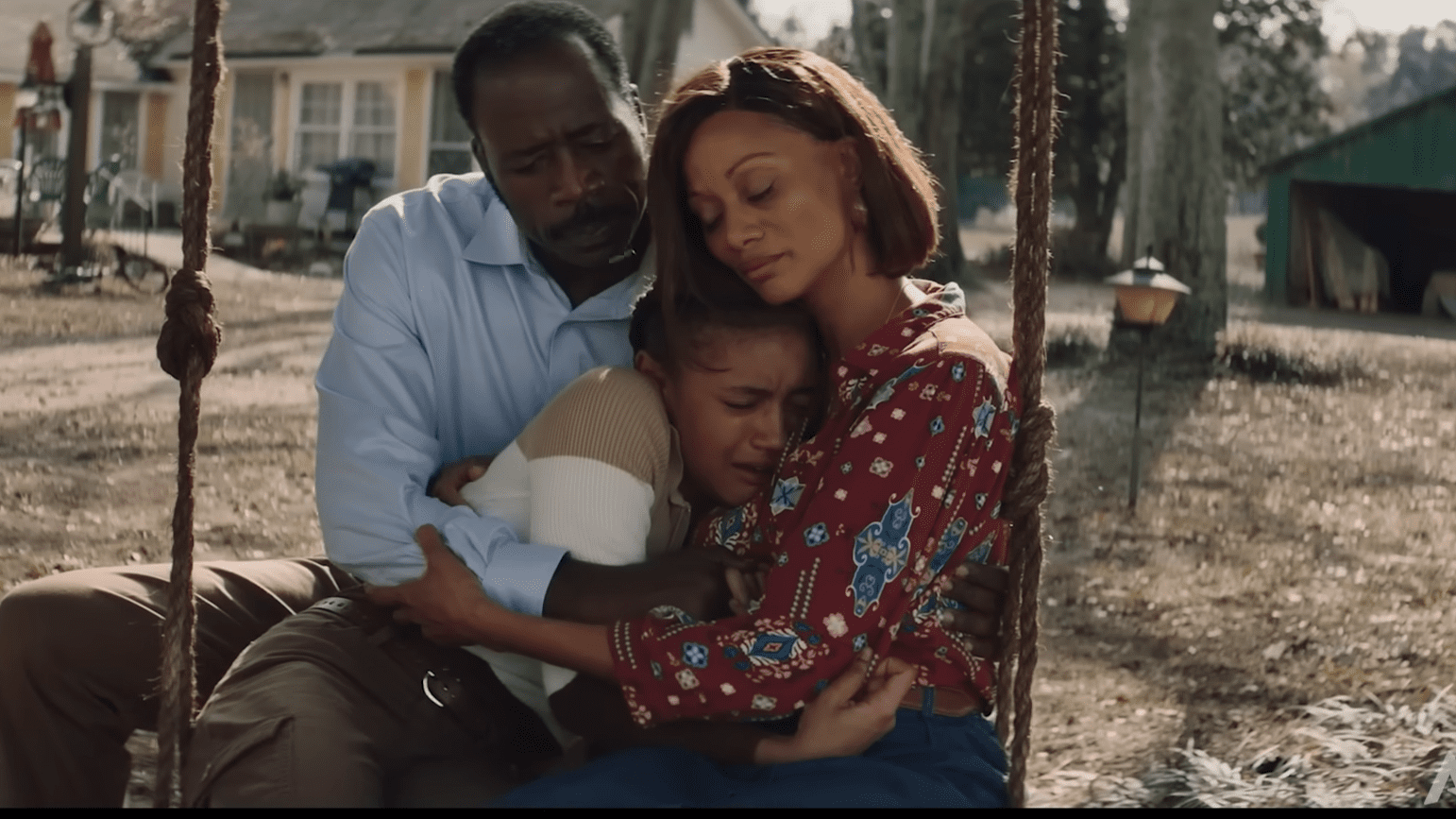

The film is directed by Joshua Weigel and co-written by Rebekah Weigel, both known for their work on the film Butterfly Circus (2009) and both adoptive parents themselves. Produced by British actress and activist Letitia Wright, best known for her role in Black Panther (2022), Sound of Hope is inspired by a true story from Possum Trot, an East Texas town where Donna (played by American actress and stand-up comedian Shenika Williams, professionally known as Nika King, best known for her role as Leslie Bennett on the HBO television series Euphoria) and her husband, Pastor Martin (played by Demetrius Grosse, an American actor best known known for his roles as Rock in the film Straight Outta Compton, Emmett Yawners in the Cinemax television series Banshee, and Errol in the FX television series Justified) are the protagonists of a story that begins in 1994. Leading by example, the couple persuade the members of the congregation to take into foster care orphaned or severely abused children who nobody else would want.

They are assisted in this effort by foster care officer Susan Ramsey (Elizabeth Mitchell, an American actress best known for starring as Juliet Burke in the ABC crime series Lost, for which she was nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award). By adopting a total of 77 troubled children, this deeply religious community demonstrated its commitment to providing a solution to the foster care crisis through determined and persistent love, or, as the film’s guide says, ‘providing proof that the fight for America’s most vulnerable children can be won’.

The movie was filmed in Macon, Georgia in the fall of 2022 and was funded entirely by donations, so most of its profits can go to children and families in crisis.

Since the studio has deliberately created a link with Sound of Freedom, I confess that I entered the theatre (this time not weeks after, but even before the premiere) with the expectation that it will be a similarly harrowing experience. Fortunately, that was not the case. Although this movie is also about child abuse with reference to its world-scale nature, unlike the previous one it is not about the deepest depths of human darkness, but

about faith, love and acceptance, as well as the power of community.

Furthermore, while in the former movie we are cheering on the lonely, almost David-against-Goliath-like struggle of an American agent, Tim Ballard (supported only by his wife and a few colleagues) against the mafia manages the sexual exploitation of children, in Sound of Hope, the officials are helpful throughout, although they themselves sometimes have professional reservations about the lifelong commitment of the leaders and members of the Possum Trot religious community, as well as about their faith and unconditional love-based approach. But ultimately, they are convinced by the community that it is up to the task.

Sound Of Hope: The Story Of Possum Trot | Carry You Trailer | Angel Studios

In Theaters July 4, 2024 Get Tickets: https://www.angel.com/hope The fight for kids begins July 4. Inspired by the powerful true story, Sound of Hope: The Story of Possum Trot, follows Donna and Reverend Martin as they ignite a fire in the hearts of their rural church to embrace kids in the foster system that nobody else would take.

Although both movies have happy endings, while the latter carries a positive message for the whole (foster care) issue, the former can only bring good news for the affected family at the centre of the plot (and the other children rescued), and only in the sense that the particular operation described was a success, while the negative psychological effects that may last a lifetime cannot be ignored. Nor can we ignore the fact that this is a ‘drop in the ocean’ kind of heroic act, as the brave hero seems to remain alone with little help from the authorities, appealing to the audience’s conscience through the emotional power of the movie to inspire action. Therefore, despite its happy ending, it fails to provide a catharsis. Although Ballard does say after the closing credits that U.S. law now allows investigation in foreign countries in similar cases, elsewhere he explains that the issue is still not a law enforcement priority.

The East Texas families depicted in the new movie also help children: they adopt abused and/or abandoned children with a difficult past that no one else wants, and who therefore come with a considerable psychological baggage. At the beginning of the process, that baggage is almost non-acknowledged by the foster parents, but problems emerge more and more strongly over time, in several families and repeatedly driving the adopters to despair or even regret. At the same time, this gives Pastor Martin an opportunity to change strategy, still based on deep faith and love, but now complemented with the power of community. A community that, while local, offers real hope that theirs might become a global practice—something that cannot (yet?) be said about the precursor movie that addresses the fight against paedophilia and child sex trafficking.

Although it may seem like just a clever advertising stunt to piggyback on the success of the previous movie by linking them through their titles, Sound of Hope is indeed about hope: about a convincing solution by which not only a family, but also the community comes together, and even the authorities are on the side of those seeking and providing the solution.

We can only hope that this could happen not only in America thirty years ago, but also today elsewhere as well. In Europe, or at least in Hungary, the situation is quite different: the foster care and adoption rules are much more bureaucratic and process-based, but the messages of the movie—child-centredness, faith, sacrifice, solidarity, cooperation with the authorities—can resonate anywhere in the world.

So does the universal message that every child should be raised in a family.

Beyond the similar titles and themes, there are other strategic parallels between the two movies. For example, during the closing credits, the main characters—in this case, three of them: the real Martins and actress Elizabeth Mitchell —call on the audience to support the cause financially, by spreading the word about it, and by taking action in relation to the 100,000 children available for foster care or adoption in the United States today. It is also articulated that the filmmakers’ goal was to highlight the crisis in the foster care system and to inspire individuals and communities to take action and change, wherever they are in the world.

While the manufactured (media) scandal surrounding the previous movie sought to divert attention from the real issue, trivializing and politicizing it by accusing the filmmakers of pushing a conspiracy theory that makes it difficult to take effective action, this is not (yet?) the case with the new movie, as foster care and adoption are much less divisive issues than paedophilia and child sex trafficking. In any case, the Rotten Tomato rating system gives Sound of Hope a score of 100 per cent for the time being, while the ten or so reviews available so far rate it at 80–90 per cent levels, mostly highlighting that it is emotional, inspiring, and encouraging.