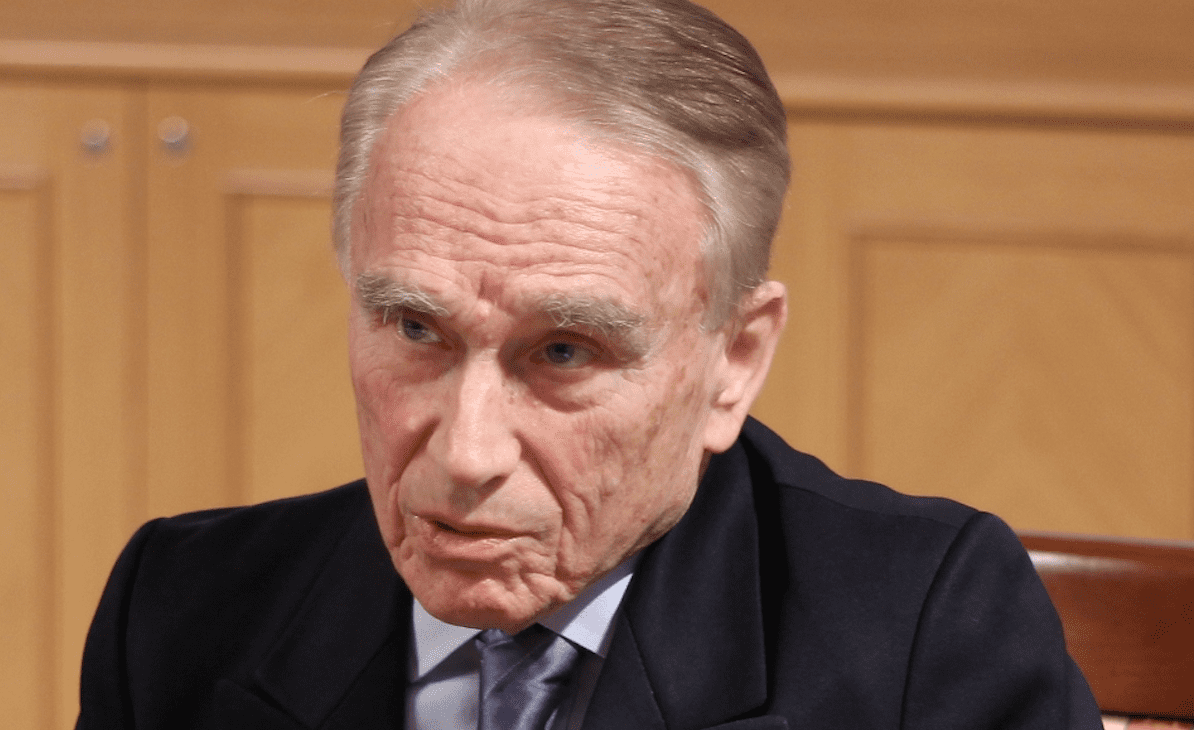

Interview with 1956er Gyula Várallyay

Julius (Gyula) Várallyay was born on 26 July 1937, in Nyíregyháza, Hungary. Gyula was a second-year university student at the Technical University in Budapest when the revolution of 1956 broke out. He was present from the beginning of the protests and was there at the first significant gathering of students where they outlined their demands. Fearing retaliation, he fled Hungary in November 1956. Although he would have preferred to remain in Europe, he ended up in the United States. I had the opportunity to sit down for an interview with Gyula in his home in Washington, DC.

Could you tell a bit me about yourself, about your childhood?

I was born in Nyíregyháza in 1937, went to school there, and I lived through World War II partly there. But then, when the Russian front was approaching, we moved a little bit northwest and ended up in Gömör County [now part of Slovakia]. So that’s where I was living when the Soviet troops came in, and the German occupying forces left. I was a relatively young child but there is a scene very deeply engraved in my memory. There were German soldiers hanging around in the village, drinking beer, and I knew some German from school.

They were showing pictures to one another about family, and they didn’t know what had happened,

the extensive bombings in Germany. It just left a very deep impression on me. Then the next morning they were gone and, in a day or two, the Soviet troops came in. We were living in a school, and we rented one larger room in a school building in the village. The Soviet troops came in and tipped over the table, and they ordered my mother to cook for them, then they left. Nothing happened. And a couple of days later, a Russian officer comes, knocks on the door, comes into the building to our room, and tries to talk to us in different languages. He was fluent in German, French, and English. It turned out he was a language teacher, but we were very cautious because we were afraid that if we started speaking with him in some foreign language, we would be accused of being spies. So, in the end, my grandfather began to talk to him in his limited Slovak because he was born and raised in northern Hungary. So, this officer comes in and begins to speak to us—a highly civilized guy. ‘Could I please have tea?’ and of course, my mother made him tea. He says, ‘You know, I’m from Vladivostok. I’m a language teacher in a secondary school. I haven’t heard from my family for a year and a half. And I am very ashamed of what our troops are doing here very often.’ And he left. Anyhow, we eventually returned to Nyíregyháza because Gömör County was reannexed by Czechoslovakia, so we had to leave. I graduated from secondary school in Nyíregyháza. I became very interested in tennis, which turned out to be very important preparation and training as in tennis, you are alone against your opponent. You have to do everything on your own to get ahead and win the game. Individual sports are perfect for training a person to be autonomous and independent.

What are your memories of the years prior to the revolution? What was life like under a communist regime?

Life under communism was, of course, not very pleasant. But as a young kid, you aren’t directly affected by misery of it. You notice it; you understand it. But you become conscious of it when you grow up because, as a child, you just experience it; you only remember the more influential, the more dramatic events. I had to get up at six o’clock to buy bread because if you didn’t get bread very early, then by the afternoon, even if you had the food coupons to buy it, there was none left. I had to get up, stand in a queue at the grocery store and take the bread home, have some breakfast and go to school. But there were also very good tennis games. As a teenager, I had a rich and dynamic life playing tennis, and started competing in as well. But overall,

it felt like there was a permanent threat of an epidemic.

The Soviets imposed a political system that was not based on the people’s wishes and desires, and this was always in the air. After I graduated from secondary school, I went on to the Technical University, where my admission was not very simple because I belonged to the ‘alien class‘, a Marxist classification of all those who were not working class. And that came with consequences, even in 1955, when I graduated from secondary school. I did not get any notification about whether I had been admitted or not as opposed to everybody else at the end of July. I didn’t get anything. And I was getting concerned and impatient. I remember my father telling me to be patient, and not to worry, as bureaucracy may be slow.

On 10 August, I finally got a message that I had been put on a waiting list. In July 1955, my father was working as the chief engineer in the local Investment Department of the County Council of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg County. The agency received a note from the party secretariat of the Technical University asking for a cadre ‘report’ on the family. Luckily, the Communist Party secretary of the agency was on summer vacation. So, the legal officer was acting as the head of the office. And went to see my father and said, ‘Look, there is this request to write about your family; I don’t know anything about your family, please prepare a report, and we’ll send it up.’ So, my father sat down and began writing a nice note, clearly in such a way as to make a good impression on the people who decided about his son’s fate. That’s how I got admitted in 1955; that’s how things worked back then. I went to the university and enjoyed it; I loved Budapest just as I love it today. I was studying, nothing extraordinary.

How was your life before the revolution? How and why did you get involved in the events of 1956?

When we returned to school in September, I was a second-year student, and everybody was talking about politics. You know, how we could live better as students, get more support and opportunities to travel to neighbouring countries, which previously was out of question. There was an important meeting of the students on 22 October, which the youth organisation of the Communist Party convened at all universities in Hungary at the same time.

They were trying to remain in charge, and of course, they had the Party’s full support.

So, they organised this meeting, the aula was full. There were easily two thousand people; the place was literally packed to the brim. When the meeting began, somehow, I don’t understand how, two students from Szeged walked onto the stage.

What is very important to know, and which nobody knew at the time, on 16 October university students had a meeting in Szeged, where they did two things: they re-established MEFESZ, a democratic student organisation started in 1945, after the war. And secondly, they formulated some demands, one of which was that the Soviet troops should leave the country. All this didn’t get any publicity, but the DISZ [Worker Youth’s Association, the de facto youth chapter of the Hungarian Workers’ Party] leaders and the party leaders knew about the decisions made at that meeting. So, they were very fearful of letting those two kids speak openly at the Budapest meeting, but there was chanting from the gallery, ‘let them speak, let them speak!’ When the two students started to speak, the DISZ, the tutors of the Marxism-Leninism department and the party secretariat’s leadership immediately left because they couldn’t deal with the anarchy of a situation where people acted in a spontaneous, unplanned way. The two rectors and, importantly, the Military Studies Department, all soldiers, remained.

The meeting was historical and fateful,

and the decisions, and the demands of the students, the 16 Points, became very well-known immediately all over Budapest and beyond.

The next day, we planned to march to the Bem [Józef Bem, a Polish general of the 1848 Revolution, a national hero in Poland and Hungary] statue, right in front of the Foreign Ministry, to stage a demonstration.

The Party first banned the meeting. But the students and some professors went to different departments in the administration. They went to the Ministry of the Interior, to the Ministry of Education, and the Party’s central office, and after all these visits and the mounting pressure, the party leaders finally gave in and said, fine. You can do the demonstration; you can march, but it must be a silent protest. On the next day, on the 23rd, the march took place. I remember two things:

people were hanging Hungarian flags from their balconies with a hole in the middle.

That was quite something. I saw several older people. We were marching, and we marched past an older couple; they were crying. And they took out a white handkerchief, and they were waving it. This scene is engraved in my memory, and it tells you a lot about the country’s mood. So, we went to the Parliament.

By that time, everybody in Budapest knew what was happening. A vast crowd was there, and they shouted, ‘we want to see, we want to hear Imre Nagy!’ After a while he stepped out onto the balcony and said, ‘Comrades’, but he was booed so then he corrected himself and addressed the crowd as ‘my fellow countrymen’. He said a few rather inconsequential words, but people were still happy with what he said, because they were happy to see him. He was the only popular politician in the country at the time. After the death of Stalin, he was put installed by the Soviets as the prime minister. He undertook what they called ‘the new course‘, with new policies that began to focus on the quality of life and the people.

He closed the forced labour camps and the internment camps; so there was a reasons why he was popular.

Then suddenly everybody started saying ‘let’s go to the radio.’ And by the time we got to Bródy Sándor street, there was already some shooting, which meant that the request of the students to have their demands broadcast was rejected. Then, out of the blue, the secret police defending the radio building started firing into the crows and shot a girl. That’s how it all started. That was around 9 or 10 at night, and suddenly, we were in a revolution.

Today when some politicians are talking about 1956, they make it seem as if people had suddenly jumped up and begun shooting at the communists. It wasn’t like that. It was a prolonged confrontation between the youth, mainly the university students, with their demands, and the officialdom, those in power. The university students’ role was that they stuck to their demands and insisting on the last point. Without that, I don’t think there would have been a revolution. The revolutionary student committees were first organised, and MEFESZ was organised. I lived in Bartók Béla street in a large dormitory for Technical University students. I remember a fellow student in our dormitory who stuttered; at one point, he asked at the large meeting at the university in his stuttering speech, ‘Why are Soviet soldiers still stationed in Hungary?’ There was a moment of silence, and then two thousand people shouted, ‘Ruszkik haza!’, meaning Russians go home.

On the 23rd, we went out onto Bartók Béla street, and we taped up flyers with the 16 points to the trees. I remember I took the tram across the bridge to Pest. When I got on, there were ticket controllers checking the tickets. When I got up, one of the men said, ‘All I want is a copy of the university student’s demands.’ I gave him one, and everybody was watching and then everyone gathered around him, trying to read what the text said. It was fascinating to experience how the mood was changing, with the events stirring up a hornet’s nest.

When did it become evident that the revolution was unsuccessful and how did you manage to get away?

The Soviets returned on 4 November to put down the whole thing the most forcefully. Major General Béla Király, the head of the National Guard, told me that the Soviets came with more tanks than Hitler did when he occupied France in 1940. And that tells you the level of military mobilisation and force they committed to putting down the revolt as soon as possible. And they were successful. That was the end of the revolution. So, the moment came when a friend of mine came and said, ‘Look, are you ready to leave?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t know, should I leave?’ to which he replied, ‘don’t be a fool.’

That fellow was the MC of the meeting of 22 October at the Technical University; he had a Rákosi [Mátyás Rákosi, the Communist leader of Hungary between 1947 and 1956] scholarship. He, like many students at the University were the first in their families to go into higher education, many coming from working class families, and I mean not only small landowner families but rural labourers. It’s vital to know that the presence of these types of young people had the most significant impact on the events, leading to the flare-up of the armed conflict.

Among them were several ex-Communists who sided with the demands of the revolution.

They realised the lies of the system, the burden of Soviet occupation, and how the system had cheated both their parents and them.

I fled with a group of seven students on 14 November, arriving in Austria on 15 November, carrying only a small case with two books and my identity papers.

What do the events of 1956 mean for Hungarians and the world in 2022, in such a crisis period?

Let me quote Zbigniew Brzezinski: ‘1956 was a defining moment in our lives.’ This tells you what the informed elite was thinking in the US: ‘It was a defining moment.’

Now, what is the meaning of 1956 today? It should be a very significant event in Hungary. I sense that today the meaning of 1956 is not necessarily what it was in 1956 and 1957, or in the 60s. Politicians are trying to use 1956 for their own immediate, daily political goals. But I think for the Hungarian nation, it should not only be a red-letter day in the calendar, but a reminder that when the nation pulls together, it can achieve remarkable things. Namely, freedom, plurality, independence, and no foreign domination through military presence; you can achieve all this when you have full unity.

One of the main points I always emphasise about 1956 is the solidarity between people.

People who had never met were ready to sacrifice their lives for each other. That should be the most important message: we can only do the best things for the country if everybody is on board. And then you don’t need to lie, enforce things, and push them on people. Because if there is comprehensive support for the rejuvenation and reinvention of the country, as it happened in 1956, that is possible. It is my conviction that we need to be thinking very seriously about 1956. It will even impact how we relate to the Russian-Ukrainian war. It impacts how we deal with internal differences of opinion and plurality. 1956 could teach us lessons in all these areas today. And I hope that wise Hungarian politicians, and we have always had them, will search this road. And I only hope that Hungary remains a leading, important Central European nation, a part of Europe.